Unit 2: Comparing Energy Choices

Overview

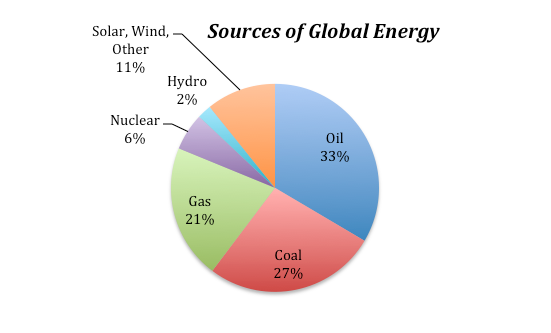

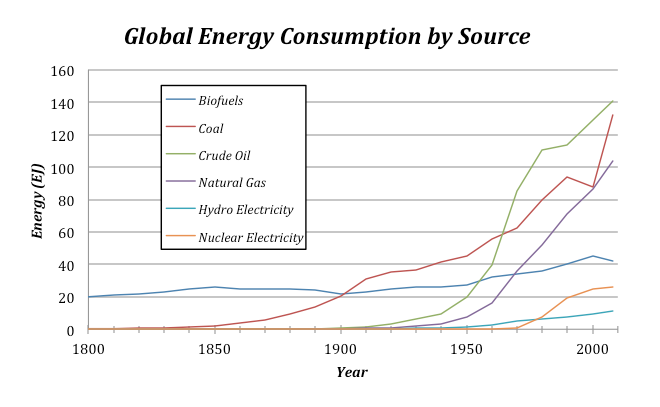

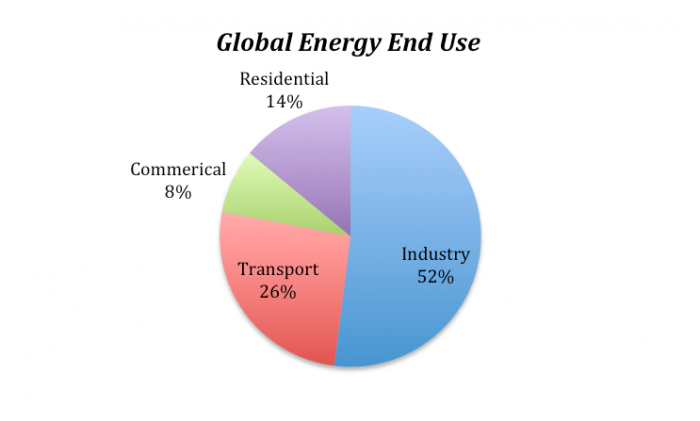

At this point in the course, we are going to take a break from thinking about how our patterns of energy utilization are affecting the planet’s climate and think about some more cheerful news – there are plenty of technological options for meeting our planet’s energy needs without the use of fossil fuels. That may seem like a bold statement – after all, our energy systems have been dominated by fossil fuels for a long, long time; are currently dominated by fossil fuels; and will likely be dominated by fossil fuels for years to come (until they simply get too expensive relative to other energy sources, perhaps helped along by public policy). Over the next couple of weeks we are going to meet a number of these technologies; learn about how they work, where they are currently being used, and where there is potential to use them even more. Our discussion is not going to focus on whether any particular technology is “good” or “bad” – what you’ll find is that these technologies may be relatively advantageous in some parts of the world and disadvantageous in other parts of the world. We are going to focus on technologies that can be used to generate electricity. Transportation and industry are also important sectors when it comes to energy utilization, but in theory transitioning the electricity sector off of fossil fuels should be a simple first step – after all, there are several thousand power plants in the United States, versus hundreds of millions of cars.

But if we have the technological means to get ourselves off of fossil fuels, then why haven’t we done so already? Is someone keeping a big secret from the rest of us?

As usual, things are not all that simple. As part of our discussions over the next couple of weeks, we’ll learn about some factors that have limited the adoption of specific low-carbon technological options. One of the things that makes comparison of technologies difficult is that there are lots and lots of dimensions to compare across. If cost were the only important factor, then there would be no problem with continuing to use fossil fuels at the rate we are currently. But it isn’t, and even “cost” is not as simple as it sounds.

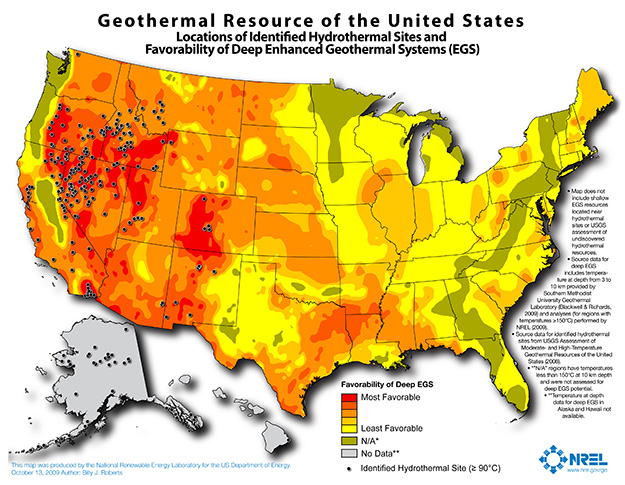

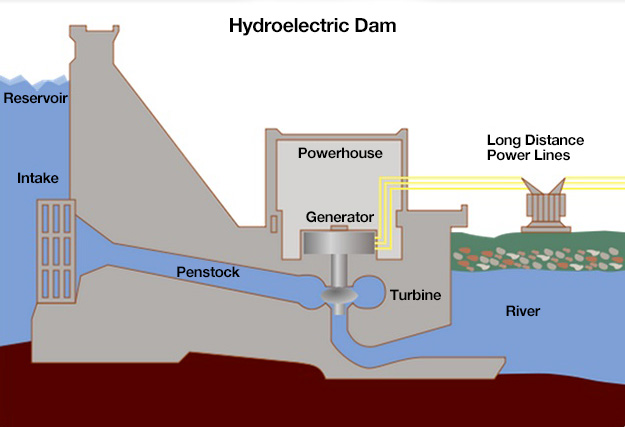

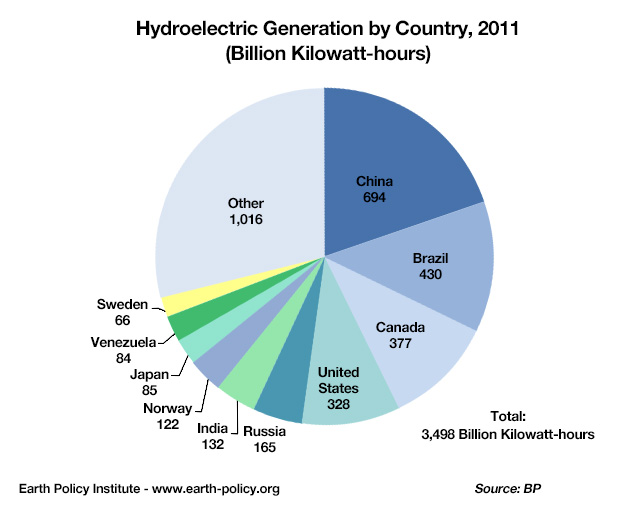

This second unit covers lessons 6-9. Dr. Seth Blumsack, Associate Professor in the Department of Energy and Mineral Engineering at Penn State, shares his deep knowledge of the many energy options available for our future use. You will learn more about solar, wind, geothermal, hydroelectric and nuclear energy, and about other options including conservation, that together can provide more than enough energy to power humanity sustainably.

- Solar and Wind (Module 6)

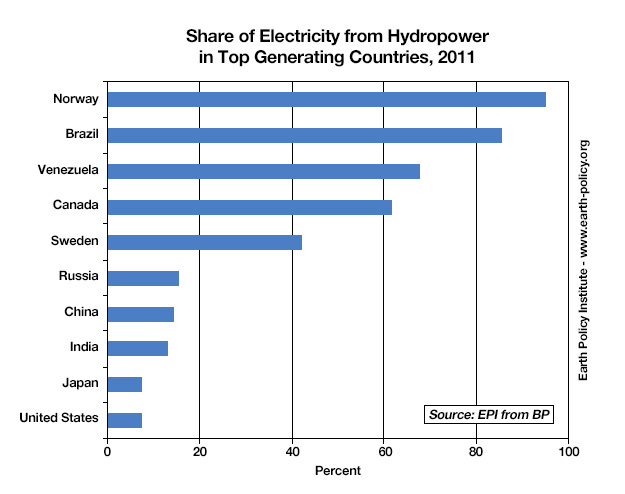

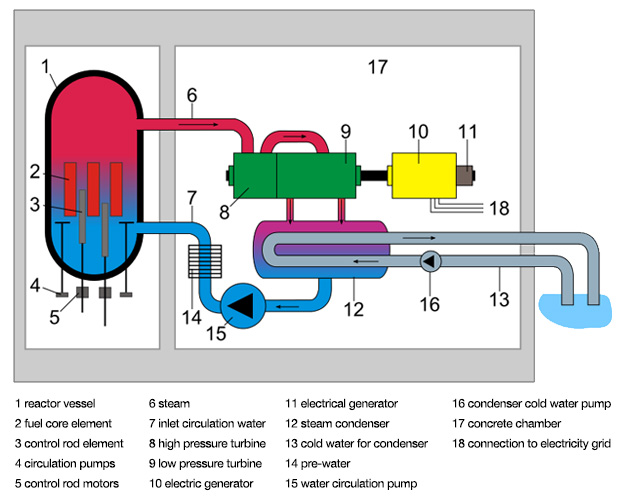

- Geothermal, Hydroelectric & Nuclear (Module 7)

- Conservation (Module 8)

- Geoengineering (Module 9)

Unit Goals

Upon completion of Unit 2 students will be able to:

- Recognize the great diversity of energy options currently available to us

- Explain scientific concepts in language non-scientists can understand

- Find reliable sources of information on the internet

- Use numerical tools and publicly available scientific data to demonstrate important concepts about the Earth, its climate, and resources

Unit Objectives

In order to reach these goals, the instructors have established the following objectives for student learning. In working through the modules within Unit 2 students will:

- Recognize the advantages and limitations of solar, wind, geothermal, hydroelectric, and nuclear energy

- Recall the basic science behind solar, wind, geothermal, hydroelectric, and nuclear power generation

- Evaluate who is responsible for maintaining "the grid" as home generation grows in popularity

- Analyze why even people who rely heavily on energy resources tend to want those resources to be exploited far from their own homes

- Recognize that all energy technologies are inefficient

- Compare wealth and energy intensity in developed countries

- Identify options for improving energy efficiency in developed countries

- Analyze why we don't always conserve as much as we should, despite the double benefits for the climate and our wallets

- Use a model to calculate the effects of various strategies such as use of renewable energy sources, conservation, and population control on reducing emissions

- Recall the various geoengineering strategies that have been suggested to mitigate climate change

- Recognize that geoengineering alone is unlikely to be sufficient to mitigate climate change

- Assess what you have learned in Unit 2

Assessments

| Module | Assessment | Type |

|---|---|---|

| 6. Solar and Wind Power | Who Pays for Home Generation? | Discussion - Express Your Opinion |

| 7. Geothermal, Hydroelectric, & Nuclear | The NIMBY Syndrome | Discussion - Find an Article |

| 8. Conservation | Emissions Scenarios | Summative - Stella Model |

| 9. Geoengineering | Learning Outcomes Survey | Self-Assessment |

Module 6: Solar and Wind Power

Overview

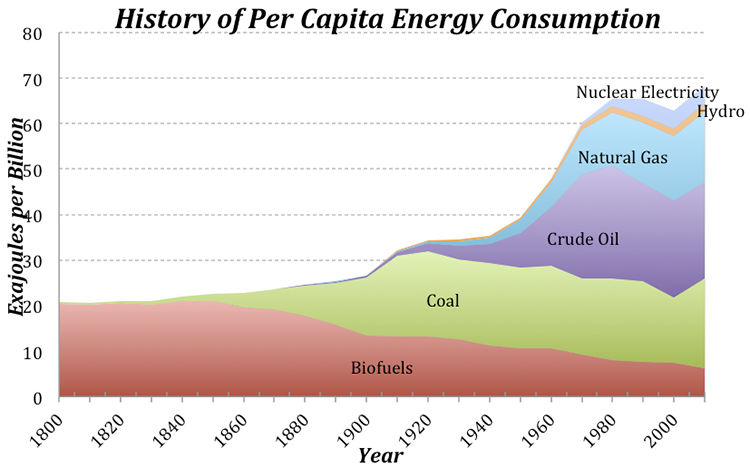

We are burning fossil fuels about a million times faster than nature saved them for us. We might continue on this path for another century or more, or we might face an “energy crisis” within a few decades as we begin to run out of fossil fuels. But, we cannot choose to rely on fossil fuels for the long-term, because they simply will not be there.

Fortunately, there are vast resources of renewable energy available. If we could collect just 0.01% of the sun’s energy reaching the top of our atmosphere, we would have more energy than is now used by all humans together. With modern technologies, a solar farm in a sunny region near the equator only a few hundred kilometers (or miles) on a side would supply more energy than we are now using. Building such a solar farm would be a huge task, but we have completed huge tasks before.

Roughly 1% of the sun’s energy goes to power the wind so we could energize all of humanity using the wind, too. Building a wind farm on just the windy parts of the plains and deserts of the world would provide much more energy than we now use. Again, there are huge challenges in actually building that many wind turbines, getting the energy where we want it, and smoothing out the effects of night and day, storm and still weather. But, no “breakthroughs” are needed, just building and improving what we already know how to do.

Using renewable energy is not a new idea. Abraham Lincoln advocated wind power, for example, and Thomas Alva Edison promoted the use of solar energy. So, let’s go see what they were thinking of, and how modern scientists and engineers have risen to their challenge.

Goals and Objectives

Goals

- Recognize the great diversity of energy options currently available to us

- Explain scientific concepts in language non-scientists can understand

Objectives

By the end of this module, you should be able to:

- Recognize the advantages and limitations of solar and wind energy

- Recall the basic science behind solar and wind power generation

- Evaluate who is responsible for maintaining "the grid" as home generation grows in popularity

Roadmap

| To Read | Materials on the course website (Module 6) | - |

|---|---|---|

| To Do | Discussion Post [1] Discussion Comments [1] Quiz 6 |

Due Wednesday Due Sunday Due Sunday |

Questions?

If you prefer to use email:

If you have any questions, please email your faculty member through your campus CMS (Canvas/Moodle/myShip). We will check daily to respond. If your question is one that is relevant to the entire class, we may respond to the entire class rather than individually.

If you prefer to use the discussion forums:

If you have any questions, please post them to Help Discussion. We will check that discussion forum daily to respond. While you are there, feel free to post your own responses if you, too, are able to help out a classmate.

Solar Energy

Solar Energy

The sun is far and away the largest potential source of energy to power things on our planet. Humans have been using the sun as an energy source for thousands of years – just think about agriculture and how that would work without sunlight – but the industry of using solar energy to create electricity is in its relative infancy. Growth is fast – in percentage terms, solar is the fastest-growing energy source on the planet. And the cost of solar power, one of its most formidable barriers, is coming down quickly as well. In this module, we’ll take a look at some of the most common technologies used to convert solar energy to electricity.

Solar Photovoltaics

Solar Photovoltaics

When most people think of “solar power,” they think about one of two things – vast arrays of solar collectors laid out in hot deserts (the left-hand panel below) or smaller arrays on rooftops or highways (the right-hand panel below). This is perhaps the most ubiquitous method of converting solar energy into electricity, but it is not the only method. These arrays of solar collectors are known as “solar photovoltaic” installations or Solar PV for short.

Solar PV installations consist of individual collectors called cells, which are packaged together in bundled modules. An individual cell does not generate enough electricity to power much of anything, which is why they must be bundled together. A single module might be enough to provide electricity for a single parking meter or roadside telephone. A number of modules can be further bundled together to form an array (see below). Multiple arrays might be needed to provide electricity for a building or a house.

There are many different kinds of solar PV cells in existence (and even more being developed in research laboratories), but they all work in more or less the same way. Unlike virtually any other type of power plant (be it coal, natural gas or wind), there is no turbine in a Solar PV cell. In fact, there are basically no moving parts at all. .

Solar PV cells harvest solar energy through a phenomenon called the photovoltaic effect, discovered in 1839 by the French physicist Bequerel. Photons of solar energy interact with electrons to “excite” them, causing them to move through conductors, thus producing an electric current. The first solar PV module was made at Bell Labs in the 1950s, but was too expensive to be more than a curiosity; in the 1960’s NASA started to use PV modules in spacecraft and by the 1970s, people started to explore their use in a wider range of terrestrial applications.

This following video explains a bit more about how Solar PV cells work and describes the different Solar PV technologies in use today. One of the potentially most important evolutions in Solar PV technology is the use of semiconducting materials other than silicon in Solar PV cells. These materials are of interest because they could, in concept, allow more of the sun’s energy to be captured on a single array. But they face barriers in the form of high costs and, in some cases, questions about the availability of raw materials.

Video: Photovoltics, a Diverse Technology (4:26)

[music]

NARRATOR: 30 years ago, the first solar cells were made of silicon. And today, silicon makes up more than 3/4 of the rapidly growing worldwide photovoltaic market. But photovoltaic, or PV cells, are also made with other semiconductor materials. Why so many types of solar cells? This diversity is due to innovation. PV materials are improving. Manufacturing costs are dropping. And PV applications are expanding. Balancing these three factors can meet demands for clean, green power, while creating more American jobs.

Innovation means improving photovoltaic materials. Every PV material absorbs sunlight differently, depending on bandgap, which is a unique electronic property of the material. Some cells absorb sunlight within the first micron of material. Others need 100 times more material to absorb the same amount of energy from the sun.

The sun's energy arrives as a combined spectrum of different wavelengths. Each color carries a different amount of energy. This makes solar cell design more complex.

If the energy of the absorbed photon matches the PV material's bandgap, then an electron-hole pair is created. If the photon has more energy, it still creates only one electron-hole pair, but the additional energy is lost as heat. If the photon has less energy than the bandgap, it is not absorbed.

Low bandgap materials absorb most of the solar spectrum, creating many electron-hole pairs, producing a high current. However, PV cells with low bandgap materials have a low voltage. High bandgap materials absorb only higher energy photons, creating fewer electron-hole pairs, producing a lower current with a higher voltage.

A solar cell's efficiency is the percentage of the solar energy, shining on the cell, that is converted into electrical energy. One way to increase efficiency is to use multiple layers, to capture power from multiple wavelengths of light. Understanding the properties of each PV material, allows scientists to improve designs that maximize the power of the cell.

Innovation in PV also means lowering the cost of manufacturing. Crystalline silicon cells have high efficiency because they used very pure single-crystalline silicon, which is expensive to manufacture. Multicrystalline silicon cells have lower efficiency, but they can be cheaper to manufacture, because they use lower quality silicon, less energy, and simpler manufacturing equipment.

Thin-film solar cells can be made for material such as-- cadmium telluride, copper indium diselenide, or amorphous silicon. These materials absorb light more readily than crystalline silicon, so they can be used in very thin layers that are less expensive to produce. Thin-film solar cells are generally less efficient than crystalline silicon cells, but they can be cheaper to manufacture because they use less semiconductor materials, which are grown on glass or flexible foil.

Finally, innovation means meeting different applications best suited by different types of solar cells. Today, PV devices produce power to meet the needs of utilities, businesses, homes, and consumer products.

Large-scale installations can use a range of highly reliable PV technologies. Solar-powered satellites are more sensitive to power per pound. These high-efficiency solar devices can accept higher material and manufacturing costs to get more electricity from less material. Flexible thin-film devices are being installed in innovative ways, including incorporation into structures with complex shapes.

Photovoltaics are here now. And the diversity of PV devices is advancing as scientists improve PV materials and develop new manufacturing methods. More solar applications are emerging, as these innovations make PV more affordable.

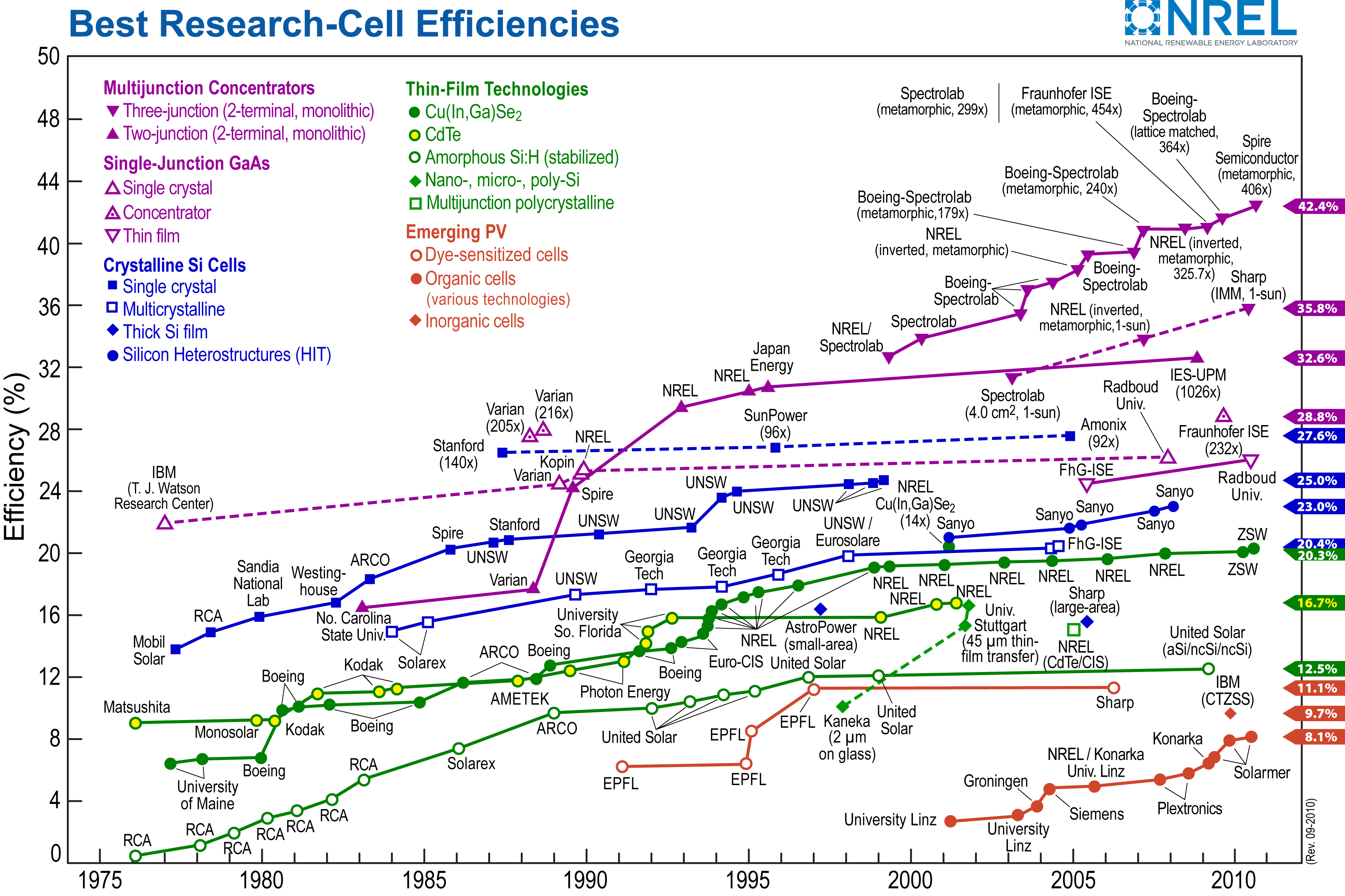

Most modern Solar PV technologies are relatively inefficient compared to other forms of electricity generation. Remember here that “efficiency” refers to how much of the fuel that is injected into an electricity generation system is actually converted into useful electricity, versus being rejected as waste heat or otherwise escaping from the generation system. While modern coal-fired and gas-fired power plants can have efficiencies as high as 60% (or sometimes even higher), most Solar PV cells convert sunlight to electricity with an efficiency of 20% or less (see below), though this number has been rising over time.

This chart from NREL (National Renewable Energy Laboratory) tracks the best research efficiencies of various solar cell technologies over time. Below is a detailed breakdown of each dataset, categorized by solar cell type, along with trends and notable efficiency milestones.

Multijunction Cells (Purple)

- Description: High-efficiency solar cells made from multiple semiconductor materials that capture different parts of the solar spectrum.

- Types:

- Three-junction (concentrator)

- Three-junction (non-concentrator)

- Two-junction (concentrator)

- Trends:

- Rapid efficiency gains from the 1980s onward.

- 1995: First exceeded 30% efficiency.

- 2005–2015: Surpassed 40% efficiency, reaching 45.5% in 2015 (record efficiency).

- Key contributors: Spectrolab, Fraunhofer ISE, Boeing-Spectrolab, NREL.

Single-Junction GaAs Cells (Pink)

- Description: Made from Gallium Arsenide (GaAs), known for high efficiency.

- Types:

- Concentrator

- Thin-film crystal

- Trends:

- 1980s: Early developments showed steady progress.

- 1995–2005: Efficiency surpassed 25%.

- 2010–2015: Efficiency reached 29–30%.

- Key contributors: NREL, Radboud, Alta Devices.

Crystalline Silicon (Blue)

- Description: The most widely used commercial solar cell technology.

- Types:

- Single crystal (Monocrystalline)

- Multicrystalline (Polycrystalline)

- Thin-film Silicon

- Silicon Heterojunction (HIT)

- Trends:

- 1980s: Efficiency ranged from 10% to 15%.

- 1990s: Research pushed efficiency beyond 20%.

- 2015: Efficiency peaked at about 26.6%.

- Key contributors: SunPower, Panasonic, UNSW, Fraunhofer ISE.

Thin-Film Technologies (Green)

- Description: Low-cost, lightweight solar cells using non-silicon materials.

- Types:

- Cu(In,Ga)Se₂ (CIGS)

- CdTe (Cadmium Telluride)

- Amorphous Si:H (stabilized)

- Nano-, Micro-, Poly-Si

- Multijunction Polycrystalline

- Trends:

- 1975–1990: Slow improvements, with efficiencies around 5–10%.

- 2000s: Notable breakthroughs, pushing CdTe and CIGS beyond 15% efficiency.

- 2015: Best CIGS efficiency reached 22.3%; CdTe around 21.5%.

- Key contributors: First Solar, NREL, ZSW, Solar Frontier, GE.

Emerging PV Technologies (Red)

- Description: Next-generation solar technologies still in early development.

- Types:

- Organic solar cells

- Organic-inorganic perovskites

- Quantum dot solar cells

- Trends:

- 2000s: Initial efficiencies below 5%.

- 2010s: Perovskite solar cells saw rapid efficiency increases, reaching over 20% by 2015.

- Key contributors: Oxford PV, UCLA, EPFL, University of Valencia.

Overall Observations

- Multijunction Cells remain the most efficient, exceeding 45%.

- Crystalline Silicon dominates commercial markets, reaching 26.6%.

- Thin-Film and Emerging PV show promise for future cost-effective solutions.

- Perovskites and Quantum Dots could revolutionize the field if efficiency gains continue.

Whether the efficiency of Solar PV cells is all that important is a matter of some debate. On the one hand, higher-efficiency cells would require less land or space to produce a given amount of electricity. Land use (or the number of rooftops) can be a significant limiting factor in the deployment of Solar PV. On the other hand, fuel from the sun is free and there is no scarcity of sunlight, so whether Solar PV cells can achieve 30% efficiency versus 20% efficiency may not be such a big deal, and may not be worth the extra economic cost to produce such high-efficiency cells.

Concentrating Solar Power

Concentrating Solar Power

If you have ever left a cold drink out in the sun during the summertime (or if you have children, if you have ever left water in the kiddie pool out in the sun for a long time), you would notice that the formerly cold water gets warm – maybe even hot. If it happens to be summertime where you are living right now, try it! Whether you realize it or not, this little science experiment is the basis for a second way of harnessing the sun’s energy to produce electricity, called “concentrated solar power” or CSP. (This technology is also sometimes called “solar thermal.”)

The following video explains how CSP works. The basic idea is that a collection of mirrors reflects the sun’s light (and heat) onto a large vessel of water or some other fluid in a metal container. With enough mirrors reflecting all of that sunlight, the fluid in the metal container will get hot enough to turn water into steam. The steam is then used to power a turbine just like in almost any other power plant technology

Earth: The Operators' Manual

Earth: The Operators' Manual

To get started, please watch the video below. This particular video will discuss the history of the idea of concentrated solar power.

Video: Lightbulbs in the Desert (Powering the Planet) (5:55)

NARRATOR: Planet Earth is awash in renewable energy. The oceans store heat and offer wave and tidal power. Plants harvest sunlight and store its energy. The Sun warms the atmosphere and sets air in motion, and we're getting better at tapping wind power. But the biggest and most promising energy source is the nearby star that lights our days and warms our world. Sunlight reaching the Earth's surface offers about 120,000 terawatts. If the Sun's energy were spread around the world, it would average around 240 watts per square meter. Richard Alley brings that huge number down to earth.

DR. RICHARD ALLEY: If I walk out into this little patch of this great desert, and I hold out my arms about like this-- And then another of me does the same thing-- And each of me is holding two 60 watt incandescent light bulbs, or 10 compact fluorescents, that's 240 watts per square meter that I'm marking out here. That's a lot of energy. And averaged across the globe, day and night, summer and winter, that's how much sunlight is available to power the planet. Let's see what it takes to turn that vast potential into energy we can use. It doesn't take a genius to know that a mirror reflects the Sun, but it does take an inventor and engineer to make the next step. Use the mirror to focus the Sun's rays on a tank filled with liquid to make steam, to drive a turbine, to make electricity, and you have concentrated solar power. That's not a new idea, but one that a little-known American inventor, Frank Shuman, pursued around 1910.

NARRATOR: In his Philadelphia workshop, Shuman invented safety glass for skylights and automobiles. He also came up with designs that could concentrate sunlight on metal tubes, heat liquid, and drive a steam turbine. But in Pennsylvania, back then, it was all about coal. Shuman had difficulty finding local backers. So in 1912, he set off for Egypt. His prototype solar farm used parabolic troughs to concentrate sunlight and boil water. The steam ran a 75 horsepower engine that pumped water from the Nile to irrigate cotton fields. The idea was right, but ahead of its time. Hobbled by both a lack of government support and adequate private capital, the experiment ended with the outbreak of World War One. These parabolic troughs look very similar to Shumans' designs, though they didn't come online until a century later.

This is Solnova 3, at one of the world's first commercial solar power plants. Just as in Shuman's experimental station, the troughs concentrate solar radiation on a pipe that contains a heat-bearing fluid. When completed there'll be three almost identical plants, each with an output of 50 megawatts, large enough to support about 26,000 households. While the Sun powers the Solucar platform, it was the Spanish government that helped develop solar power. The central government set a specific target of 500 megawatts of concentrated solar power and committed to price supports for 25 years. That, in turn, unleashed inventors and industry to prototype plants like this one. The technology works, though changing government policies and the budget crisis have impacted the industry. But, Abengoa, the company building Solucar, is a part of a consortium planning the world's largest solar power project. Formed by a group of European and North African companies and the DESERTEC Foundation, this consortium has energy ambitions that are revolutionary for both Europe and the Middle East.

Unlike some of its neighbors, Morocco has little oil or other fossil fuels. But it does have sun, sand, and empty spaces. The Moroccan government has encouraged the use of distributed solar power by small businesses and individuals. Already, out on the edge of the Sahara, you can see photovoltaic panels on top of tents. But the Desertec vision goes beyond this by including concentrated solar power plants, photovoltaic installations, and wind turbines, linked with low-loss, high-efficiency transmission cables back to Europe. The Desertec project estimates that solar power from the Sahara could provide more than 80% of North Africa's needs, and 15% of Europe's electricity, by 2050. In a single generation, Morocco's young and growing population could go from energy poverty to energy independence. The energy created by this proven technology could generate both electricity and income for some of the world's poorest nations. And updated versions of Shuman's century-old designs and a smart grid could go a very long way toward meeting our species' need for energy. Collecting just 10% of the Sun's energy from a 600-mile-square of low-latitude desert would supply roughly twice today's human consumption of energy.

Recently, more advanced CSP systems have begun to replace the water or synthetic oil with molten salt, as the fluid that is heated molten salt can remain as a liquid from 290 to 550°C. Once it is heated in the tower at the center of the array of mirrors, the hot liquid salt is stored in a highly insulated tank and when there is a demand for electricity, it is sent to a heat exchanger where it turns water into steam, driving the turbine to generate electricity. When the molten salt passes through the heat exchanger, it gives up heat, so it cools off. It is then recirculated to the tower at the center of the mirrors, where the concentrated sunlight heats it back up. These systems have enough liquid salt so that it can act as a thermal battery, storing the solar energy for more than a week before it cools off to the point where it cannot make steam. These kinds of power plants are expensive at the moment, but the technology is still quite new and so we expect prices to drop quickly, as they have for other renewable energy technologies. In fact, a CSP system in Spain using molten salt is now capable of producing energy on demand, 24 hrs a day rather than being limited to times of peak sunlight. The ability to schedule power production versus having to take the electricity when it comes is of great value to the folks that operate electricity systems. Nevertheless, there are still a few obstacles for CSP:

- CSP is difficult to make work on a small scale. A lot of land, usually in sunny deserts, is typically needed. So CSP does not scale up and down to large and small installations like Solar PV can.

- CSP is currently quite expensive — roughly twice as much per unit of energy as Solar PV. However, this is a very new technology and prices are expected to go down in the future.

Solar Energy Potential and Utilization

Solar Energy Potential and Utilization

In addition to being free as a source of energy (it does cost money to harness it and turn it into electricity), energy from the sun is practically limitless. The surface of the Earth receives solar energy at an average of 343 W/m2. If we multiply this times the surface area of the Earth, about 5x1014 m2, we get 1715x1014 W. But, 30% of this is reflected, and only 30% of the Earth is above sea level, so the usable solar energy we receive on the land surface is about 360x1014 W. We need to reduce this further because not all of the land surface is suited to installation of solar PV panels — we don't want to cut down forests, and ice-covered areas are not suitable, so we reduce the area by about one half. Over the course of a year, this amount of solar energy adds up to 66x1022 Joules. In 2018, we used about 600x1018 Joules of energy, which is just a shade less than 0.1% of the harvestable solar energy we receive on the land. This means that even if we got all of our energy from the Sun, we would not make a dent in the total! The potential is vast — 10,000 times what we need!

Let’s consider what it would mean for us to get all of our energy from Solar PV — how much of the Earth’s surface would we need to cover with panels? The black dots (radii of 100 km) in the figure below represent areas that could generate enough energy from sunlight to completely power the planet for an entire year. Practically, there are barriers to running the planet entirely on sunlight (everything would need to be electrified, we would need very large quantities of battery energy storage, and so forth), but the dots are useful as a demonstration of just how vast the energy production potential from solar is.

This image is a world map illustrating the annual mean solar potential across the globe, measured in watts per square meter (W/m²). The map is sourced from Matthias Loster, 2006, and includes a total solar potential estimate of 18 terawatt-equivalents (TWe) indicated in the bottom right corner with the symbol "Σ⦿ = 18 TWe."

Map Overview:

The map shows a global view with continents outlined in black, including North and South America on the left, Africa in the center, Europe and Asia above, and Australia on the right. The background is a gradient of colors representing solar potential, with a color scale at the bottom ranging from purple (lowest) to red (highest)

- Color Scale:

The color bar at the bottom ranges from 0 to 350 W/m2. Purple represents the lowest solar potential (0–50 W/m2), transitioning through blue (50–100 W/m²), green (100–150 W/m2), yellow (150–200 W/m2), orange (200–300 W/m2), and red (300–350 W/m2) for the highest solar potential. - Solar Potential Distribution:

- High Solar Potential (Red/Orange): Areas with the highest solar potential (250–350 W/m2) are concentrated near the equator, including Central Africa, the Middle East, northern Australia, and parts of the central Andes in South America. These regions appear in shades of red and orange.

- Moderate Solar Potential (Yellow/Green): Moderate solar potential (150–250 W/m2) spans much of South America, Southern Africa, India, Southeast Asia, and northern Australia, shown in yellow and green shades.

- Low Solar Potential (Blue/Purple): Areas with the lowest solar potential (0–150 W/m2) include the polar regions, northern North America, Northern Europe, and parts of Russia, depicted in blue and purple shades

- Black Dots:

Several black dots are scattered across the map, likely representing specific locations or solar energy projects. These dots are located in the southwestern United States, central South America, central and Southern Africa, the Middle East, India, and northern Australia. - Additional Details:

The map uses a gradient color scheme to visually represent the intensity of solar potential, with equatorial regions showing the highest potential due to their proximity to the sun’s direct rays. The source, "Matthias Loster, 2006," is noted in the bottom right corner.

It’s kind of amazing to see how little area of the Earth would need to be covered to achieve this.

Optional Resource

If you are interested in a more detailed view of solar energy resources in your area, a company called Vaisala 3Tier [14] produces maps that you can download for your own personal (non-commercial) use.

One of the important differences between Solar PV and CSP is that CSP requires more intense sunlight, and as such, it is not a viable option in many places. In contrast, Solar PV works just about everywhere — it is more versatile. Another important difference is in scale — CSP is really suited to utility-scale power plants, whereas Solar PV works at both the utility-scale and the very small scale.

The map below shows the PV potential for the world. The variability in the map is mainly a function of cloudiness and latitude. Many of the big, utility-scale solar PV plants are located in the red areas, but there is a surprising amount of Solar PV energy being harvested in places like Germany and Japan, both of which are fairly cloudy. But, even in a fairly cloudy place like Pennsylvania, you can see from the map that we could expect about 1460 kWh per year from a 1 kW PV array. From this, you can calculate how many square meters of PV panels you’d need to provide the electricity for a house that uses the typical 10,800 kWh per year. If you divide 10,800 kWh by 1460, you see that you’d need about 7kW of solar panels, which would fit on a typical house roof. The main point here is that Solar PV is a viable energy source in most parts of the world where people are living. In contrast to Solar PV, energy from CSP is only viable in places where the daily totals in the map above are higher than 6 kWh/day. Nevertheless, there are many regions where CSP viability and human population coincide, so it too can be an important energy resource in the future.

Activate Your Learning

For students living in the United States: According to the map above, do you live in an area that can support PV generation? What about CSP? Do you know anyone who generates solar power at home?

Click for the answer.

The Changing Economics of Solar Energy

The Changing Economics of Solar Energy

The generation of solar energy – primarily through Solar PV – is a story of exponential growth. Since 2000, the global Solar PV industry has grown by around 25% per year on average, so installed capacity has been doubling every 2.7 years (see below). Even so, solar represents a very small sliver of total global power generation — for now.

The nice thing about exponential growth is that it is easy to project it into the future. Over the time period shown in the graph above, solar energy generation has grown by 25% per year; if we continue that into the future, we find that before long, we would have enough solar energy to make up a substantial portion of the global energy needs by 2030 (see figure below). By the year 2040, this growth would rise to 1360 EJ, more than twice the global energy consumption of the present. Of course, that makes no sense — we would not produce more energy than we need, and this reminds us of an important fact, which is that exponential growth cannot continue forever.

The image is a line graph titled "Global Solar Energy Generation Projection," depicting projected solar energy generation from 1985 to 2030. The x-axis represents the year, ranging from 1985 to 2030, and the y-axis represents the energy generated per year in exajoules (EJ), ranging from 0 to 120. The graph starts with a nearly flat blue line from 1985 to around 2015, indicating little to no growth in solar energy production. After 2015, the line turns orange and begins to curve sharply upward, showing a significant increase, projecting exponential growth in solar energy generation up to 2030. A text box within the graph notes "Projection into the future assuming 25% per year growth."

One reason to trust this projected future growth is that the price of solar energy has fallen dramatically over time as can be seen in the graph below. In fact, if the generation of solar PV energy has been growing exponentially, the price has been dropping exponentially.

This bar chart illustrates the decline in the cost of silicon photovoltaic (PV) cells from 1977 to 2015, measured in US dollars per watt ($/Watt).

Key Observations:

1977:

-

- The price of silicon PV cells was $76.00 per watt, the highest recorded in the dataset.

- Marked by a tall blue bar at the far left.

1980s:

-

- Significant price reduction as PV technology improved.

- By 1985, the price dropped to around $10 per watt.

- The bars become progressively shorter, showing a steep decline.

1990s:

-

- The price stabilized around $5–10 per watt.

- The bars maintain similar heights, indicating slower reductions.

2000s:

-

- Continued gradual decline, reaching around $2 per watt by mid-2000s.

- More efficient manufacturing and increased adoption contributed to lower costs.

2015:

-

- The price reached $0.30 per watt, as indicated by a highlighted blue label at the bottom right.

- This marks a 99.6% reduction from 1977 prices.

Additional Details:

- A text box in the center of the graph reads:

"Price history of silicon PV cells in US$ per watt" - Data Source: Bloomberg New Energy Finance & pv.energytrend.com

- The trend follows Swanson’s Law, which states that solar PV prices drop by 20% for every doubling of cumulative shipped volume.

The price decrease is following a pattern that has been given a name: Swanson’s Law, which states that the price drops by about 20% for each doubling in the number of PV cells produced. This law suggests that the prices of solar PV energy will continue to decline in the future.

This brings us to an important question — how does the cost of solar energy compare to other sources of energy? Energy economists have come up with a good way of comparing these costs by adding up all of the costs related to producing energy at some utility-scale power plant (a big wind farm, a big solar PV array, a CSP plant, a nuclear plant, a gas or coal-burning power plant). This is called the levelized cost of energy, and you get it by taking the sum of construction costs, operation and maintenance costs, and fuel costs over the lifetime of a plant and then dividing that by the sum of all the energy produced by the plant over its lifetime. This cost provides us with a way of comparing the energy from different sources. Since the boom in natural gas production due to fracking, natural gas has been the lowest cost form of energy (which is why coal is being used less and less), but energy from solar and wind have been decreasing rapidly, as can be seen in the following graph. When a renewable electrical energy resource such as solar or wind becomes equal in cost to the cheapest fossil fuel source of electricity, we say that the renewable resource has reached "grid parity". Once grid parity is achieved, the renewable resource makes sense from a purely economic standpoint, and as it drops below the grid parity point, it is the smartest electrical energy resource.

This line graph displays the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) for solar, wind, and natural gas from 2008 to 2018 in 2018 dollars per megawatt-hour (MWh). The LCOE represents the total cost of generating electricity from each source, considering installation, maintenance, and fuel costs.

Key Observations:

Solar Energy (Red Line)

-

- In 2008, the LCOE for solar was about $180 per MWh, the highest of the three energy sources.

- The cost declined rapidly over the years, reaching approximately $40 per MWh by 2016.

- By 2018, solar became the cheapest energy source at under $30 per MWh.

- The decline reflects advances in solar panel technology, manufacturing efficiency, and increased adoption.

Wind Energy (Green Line)

-

- The cost of wind energy fluctuated between $60–80 per MWh from 2008 to 2010.

- After 2010, wind costs began to decline, reaching a low of about $20 per MWh in 2018.

- The drop can be attributed to larger and more efficient wind turbines, better grid integration, and falling installation costs.

Natural Gas (Blue Line)

-

- The LCOE for natural gas remained relatively stable, fluctuating between $40-60 per MWh over the period.

- Natural gas was cheaper than solar for most of the timeline but was surpassed by both solar and wind by 2018.

- The stability of natural gas prices is due to fuel costs, infrastructure maintenance, and policy factors.

Overall Trends:

- Solar energy saw the most dramatic cost reduction, making it one of the cheapest electricity sources by 2018.

- Wind energy also experienced a significant drop, becoming the least expensive energy source by 2018.

- Natural gas remained relatively stable, but was no longer the most cost-effective option by the end of the period.

Part of the reason that solar and wind have expanded in recent years has to do with government policies — a number of countries have instituted subsidy and incentive programs that offset a large portion of the construction/installation costs of solar and wind technologies or devise rules that otherwise give advantages to electricity generation from renewables. Subsidies enacted in various countries have included feed-in tariffs (which guarantee an above-market sales price for solar power); rebates (which directly offset capital and installation costs); and favorable tax treatment (which is like an indirect feed-in tariff). Germany has one of the world’s largest Solar PV markets not because it has the best solar resource on earth but because it has been willing to support a generous feed-in tariff on solar power. (For many years the tariff was over 30 cents per kilowatt-hour, or more than five times the average power price in the United States; in recent years the tariff has been reduced.) These government policies have effectively stimulated the growth of these renewable energy resources, which has, in turn, resulted in lower prices.

Wind Energy

Wind Energy

By this point in the course, you have been told repeatedly that our energy and electric power systems are dominated by fossil fuels. And this is true. But you may be surprised to know that in the United States and many other countries, wind is among the fastest-growing sources of new power plant investment, as measured by megawatts of new capacity. In several areas, including Texas and the Mid-Atlantic (where a boom in fossil fuel production is currently underway), wind power is the largest source of new electrical generation capacity, making up a majority of new plants. That’s right – in oily Texas, more than 50% of new electrical generation in recent years has been from wind. In fact, Texas is the US leader in wind energy generation – much more than even California, which has somewhat greener political leanings.

In this section of the course, we’ll take a look at what’s going on in all those tall towers sprouting up along ridgetops and plains – and out in the middle of the ocean, in some places. Humans have been harnessing the wind to do useful work in one fashion or another for many thousands of years – the first “wind energy” systems were actually sailboats. Humans have also been smart enough to realize that wind is a very useful cooling mechanism on hot days. So in some sense, the windows in our houses are a form of wind energy. Windmills (the precursor to today’s wind turbines) appear to have first been used in Greece around two thousand years ago.

How Wind Turbines Work

How Wind Turbines Work

In a conventional power plant (fueled by coal or natural gas), combustion heats water to steam and the steam pressure is used to spin the blades of a turbine. The turbine is then connected to a generator, which is a giant coil of wire turning in a magnetic field. This action induces electric current to flow in the wire. The workings of a wind turbine are much different, except that instead of using a fossil fuel heat to boil water and generate steam, the wind is used to directly spin the turbine blades to get the generator turning and to get electricity produced.

The inner workings of a wind turbine consist of three basic parts, seen in the figure below. The tower is the tall pole on which the wind turbine sits. The nacelle is the box at the top of the tower that contains the important mechanical pieces – the gearbox and generator. The blades are what actually capture the power of the wind and get the gears turning, delivering power to the generator. The direction that the blades are facing can be rotated so that the turbine always faces into the wind, and the pitch of the blades (the angle at which the blades face into the wind) can also be adjusted. Pitch control is important, especially in very windy conditions, to keep the gearbox from getting overloaded.

The amount of power (in Watts) collected by a wind turbine is explained in the following equations:

This figure explains the physics of wind power. So we begin with this notion of the moving wind having some kinetic energy which is 1/2 m v2. So that is kinetic energy. Power is related to energy in the following way: It is energy per unit of time. So if we want the power that we can get from that moving wind, we have to take the kinetic energy, and then the mass flux rate instead of just the mass. Mass flux rate is how much mass is moving per unit of time. That is dm over dt, change in mass over change in time. And that is equal to the air density times the area swept out by the windmill blades times the velocity, so that velocity and area multiplied together gives you something with the units of measure are cubic meters per second, and then you multiply that by the density and that gives you kilograms per second and that’s the mass flux rate. If you put all that together, you see the wind power is equal to one half times the air density times the area swept by the blade times the velocity cubed. So you see, the velocity is super important in this. Now then it turns out that there is an efficiency limit, something called the “ Betts Limit” that means that the power you can actually collect is 0.3 times the air density times the velocity cubed.

The Kinetic Energy (KE) of the wind is:

Where m = mass, and v = velocity of wind.

Power (P) in the wind is the KE per unit time, so we replace the mass(m) with the mass flux rate dm/dt:

Where p = air density, and A = swept area of blades.

So the wind Power(P) is:

If the wind turbine collected all of this power, the wind would have to stop and the blades would stop spinning. If you want the blades to keep spinning, it turns out that you can collect about 60% of the power (called the Betz limit).

So, collectible Power(P) is:

How much power could we get with a turbine whose blades are 100m long, with a wind speed of 10m/s (about 22mpg>, with an air density of 1.2kg/m2?

This is clearly a lot of power! But, mechanical inefficiencies related to the gears and the generator mean that we might only get 30% of this figure, but that is still a lot of power from one turbine.

All wind turbines have a minimum wind speed that differs depending on the size but is typically about 4-5 m/s (10 mph) and maximum wind speed above which they shut down to avoid damage, usually around 20-25 m/s (about 50 mph). Most wind turbines have a maximum spinning rate, reached a bit above the minimum velocity, and when the wind speeds up, the pitch of the blades is adjusted so that the rate of spinning remains more or less constant. The figure below shows a typical "power curve" for a small wind turbine.

This figure shows the power curve for a 1.5 megawatt wind turbine. So on the Y-axis is the power and the X-axis is the wind speed in miles per hour. And what you can see is that there is sort of a threshold speed that is something like 6 miles per hour wind speed you start to get some power. And as the wind speed increases, the power output rises rapidly until you get to about 30 miles per hour. At that point the power sort of saturates and flattens out and with more wind you don’t get any more power. So it reaches its capacity at 1.5 megawatts and it generates that up until 50 miles per hour and above that the power drops off rapidly because the wind turbine has a shut off mechanism will turn off if the wind gets going to fast because of the turbulence that can cause damage to the wind turbine. So they just shut down if the winds get to great.

The wind, as you may have noticed, is highly variable in any given place, but as a general rule, it is stronger and steadier as you rise up above the ground. This is because friction between the wind and the land surface slows the wind. But there is also a lot of regional variation in the wind velocity. Both of these factors (elevation above the ground and location) can be seen in the maps below, showing the average wind speed in the US at two different heights.

These two maps of the United States show the average annual wind speed at two different heights above the surface. The upper map shows the wind speed at 30 meters height and the one below shows it at about a hundred meters. You can see a couple thing right away. One is that there is just a lot more wind at greater velocities at this higher elevation above the lands surface. You get to 100 meters and there are a lot of places in the central part of the US where you get wind speed from 8 to 10 meters per second, which is really moving along quit fast. And you also see this lower map of 100 meter of wind speeds of the offshore regions everywhere on the west coast and the east coast and around the Gulf of Mexico there are very high wind speeds. Also the Great Lakes are like this. The primary reasons these offshore regions have such high wind speeds and also why higher up you have such wind speeds are because there are less friction in those settings. So you go higher up from the surface there is less friction from the air and all the trees and the roughness of the land surface. That roughness slows the wind down and as you rise above that to 100 meters you get away from that disturbance and have higher wind velocities. You can also see that in the mid-continent region, both the 30 meter and the 100 meter heights, that’s the area with the greatest wind potential. You have these annual average wind speeds that are quit high and this is primarily because this is flat part of the country. There are not a whole lot of topography in those areas so the winds can really get going and be maintained. They do not encounter mountains and valleys and the sort of complexity that you see in other areas where further out west the wind speeds are not that high. So you can look at this and see right away that if you wanted to develop wind power, the best places are in the middle of the continent and at a high elevation 100 meters above the surface. That is why you see so many tall wind turbines to get up that high.

These two maps of the United States show the average annual wind speed at two different heights above the surface. The upper map shows the wind speed at 30 meters height, and the one below shows it at about a hundred meters. You can see a couple thing right away. One is that there is just a lot more wind at greater velocities at this higher elevation above the land's surface. You get to 100 meters and there are a lot of places in the central part of the US where you get wind speed from 8 to 10 meters per second, which is really moving along quite fast. And you also see this lower map of 100 meter of wind speeds of the offshore regions everywhere on the west coast and the east coast and around the Gulf of Mexico there are very high wind speeds. Also, the Great Lakes are like this. The primary reasons these offshore regions have such high wind speeds and also why higher up you have such wind speeds are because there are less friction in those settings. So you go higher up from the surface, there is less friction from the air and all the trees and the roughness of the land surface. That roughness slows the wind down and as you rise above that to 100 meters you get away from that disturbance and have higher wind velocities. You can also see that in the mid-continent region, both the 30 meter and the 100-meter heights, that’s the area with the greatest wind potential. You have these annual average wind speeds that are quite high, and this is primarily because this is a flat part of the country. There are not a whole lot of topography in those areas, so the winds can really get going and be maintained. They do not encounter mountains and valleys and the sort of complexity that you see in other areas, where further out west the wind speeds are not that high. So you can look at this and see right away that if you wanted to develop wind power, the best places are in the middle of the continent and at a high elevation 100 meters above the surface. That is why you see so many tall wind turbines to get up that high.

The graphs above show annual average wind speeds in the US at 2 different heights above the ground surface. For reference, 10 m/s is 22.3 mph. You can see that the wind speeds at 100 m are far greater than at 30 m — this is the friction effect of the land surface (which is minimal above large water bodies). As you can see, the Great Plains have great wind potential, as do the Great Lakes and offshore areas on both coasts.

The area covered by the turbine’s blades is another important factor in determining power output. While wind turbines are available in a wide variety of capacities, from a few kilowatts to many thousands of kilowatts, it’s the larger turbine sizes that are being deployed most rapidly in wind farms. Several years ago the image on the right side of the figure below of a Boeing 747 superimposed on a wind turbine gave an astonishing representation of the scale of the state-of-the-art wind technology. Now, turbine rotor diameters are approaching the size of the Washington Monument!

The image is a graph that illustrates the progression of rotor diameters of wind turbines over time, comparing them to the wing span of an Airbus A380.

- The x-axis represents the years from 1985 to 2010 and beyond, with specific years marked: '85, '87, '90, '91, '93, '95, '97, '99, '01, '03, '05, '10, and an estimated future point labeled as "1ˢᵗ year of operation" with a capacity range of 8 to 10 MW.

- The y-axis represents the rotor diameter in meters (m), ranging from 15 meters to 250 meters.

- The graph shows a series of circles, each representing the rotor diameter of wind turbines at different points in time. These circles increase in size as the timeline progresses, indicating the growth in rotor diameter over the years.

- Each circle is labeled with its corresponding rotor diameter:

- 1985: 15 m

- 1987: 30 m

- 1990: 40 m

- 1991: 50 m

- 1993: 60 m

- 1995: 70 m

- 1997: 80 m

- 1999: 90 m

- 2001: 100 m

- 2003: 110 m

- 2005: 120 m

- 2010: 130 m

- Future (8-10 MW): 250 m

- A red line runs through the centers of these circles, showing the trend of increasing rotor diameter over time.

- On the right side of the graph, there is an illustration of an Airbus A380 with a wing span of 80 meters for comparison. An arrow points from the Airbus A380 to the largest circle (250 m), suggesting a comparison between the wing span of the airplane and the rotor diameter of future wind turbines.

- The background of the graph is light blue, and the circles are shaded in orange with red outlines.

This graph visually demonstrates the significant increase in wind turbine rotor diameters over the years, projecting into the future with much larger sizes compared to current standards.

Activate Your Learning

Given that the area of wind captured by the turbine is proportional to the square of the radius (essentially the length of the blade), if you were to double the length of a wind turbine's blade, how much more power would that turbine generate? Assume that wind speed and all other variables remain the same.

Click for the answer.

Market Deployment of Wind Energy

Market Deployment of Wind Energy

Market Deployment of Wind Energy

Over the last 20 years, growth in the total installed capacity of wind energy generation across the globe has been growing rapidly. Germany was the first country to lead the development of wind power, but the US and China have dominated the growth since 2010. China is especially impressive in terms of its recent growth.

The image is a line graph titled "Cumulative installed wind energy capacity, gigawatts," which shows the growth in installed wind energy capacity from 1997 to 2016 for several countries. The y-axis represents the capacity in gigawatts (GW), ranging from 0 to 140 GW. The x-axis represents the years from 1997 to 2016.

- China (green line) shows the most significant growth, starting from near 0 GW in 1997 and rising sharply to over 140 GW by 2016.

- United States (red line) starts with a low capacity in 1997 but increases steadily, reaching around 80 GW by 2016.

- Germany (blue line) also shows steady growth, starting from a low base and reaching approximately 45 GW by 2016.

- Spain (orange line) has a moderate increase, peaking at around 25 GW.

- India (purple line) starts from almost 0 GW and grows to about 30 GW by 2016.

- United Kingdom (light blue line), France (dark blue line), and Italy (yellow line) all show growth, but at a slower pace compared to the top countries, with capacities below 20 GW by 2016.

The graph is sourced from the BP Statistical Review of Global Energy and is provided by Our World in Data. Each country's line is color-coded for easy differentiation, with a legend on the right side of the graph identifying each color with its respective country. The overall trend indicates a global increase in wind energy capacity over the years, with China leading significantly.

Part of the reason for this growth is the steady decline in the cost of wind energy, as discussed in the previous section on solar energy. But government policies are another important factor. The United States has one of the most volatile markets for wind energy in the world, while those in Europe and China have been among the most stable. This is due in part to differences in how governments in these countries treat wind energy. In many parts of Europe, wind energy (and other renewable generation technologies) enjoy subsidies and incentives known as feed-in tariffs. The feed-in tariff is essentially a long-term guarantee of the ability to sell output from a specific power generation resource to the grid at a specified price (typically higher than the prices received in the market by other generation resources). The United States, on the other hand, has favored a system of tax incentives called the “Production Tax Credit” (PTC) to encourage renewable energy deployment. In theory, a tax incentive should not work much differently than a feed-in tariff (both are just payments based on how many kilowatt-hours are generated). But the PTC has historically needed to be re-authorized frequently by the US Congress – this “on-off” policy strategy has been a major factor in the volatility of wind energy investment in the US as shown in the figure below. It is worth noting that the PTC was recently renewed for 2013, but will lapse again at the end of 2019, so it is difficult to say what impact it will have on wind investment going forward.

The image is a bar graph titled "Annual U.S. Wind Power Installation," which shows the amount of wind power installed in the United States each year from 1998 to 2018, measured in megawatts (MW).

- The y-axis represents the installed wind power capacity in MW, ranging from 0 to 14,000 MW.

- The x-axis represents the years from 1998 to 2018.

Key points from the graph:

- From 1998 to 2004, the installation of wind power was relatively low, with figures below 2000 MW each year. There is a notable annotation "PTC lapse" pointing to the years 1999, 2000, 2001, and 2003, indicating periods where the Production Tax Credit (PTC) lapsed, leading to lower installations.

- Starting in 2005, there is a noticeable increase, with installations generally above 2000 MW, peaking around 2008-2009 with over 10,000 MW.

- Another significant peak occurs in 2012, reaching over 12,000 MW, followed by a sharp decline in 2013, again marked with a "PTC lapse" annotation.

- From 2014 to 2018, the installations fluctuate but remain relatively high, with values generally between 6,000 MW and 8,000 MW, except for another peak in 2015.

The bars are colored in shades of red, with darker shades representing higher values. The graph visually represents the impact of the PTC lapses on the annual installation of wind power, showing significant drops in those years.

The above clarifies that government policies are important to the growth of renewable energy production (both wind and solar). In a very real way, you can think about these policies (feed-in tariffs or tax credits) as a form of investment. Governments can also provide investments in the form of funding for basic research related to these technologies. In general, these investments do not add up to a huge amount when seen in the context of a country's gross domestic product (GDP), which is a measure of the size of the economy, as seen in the figure below.

The image is a horizontal bar chart titled "Renewable Energy Investment (% of GDP), 2015," which shows the percentage of each nation's gross domestic product (GDP) invested in renewable energy in 2015. The data source is Bloomberg New Energy Finance and the World Bank, provided by Our World in Data.

- Chile has the highest investment at 1.4% of GDP.

- South Africa also invests 1.4% of its GDP in renewable energy.

- China follows with 0.9% of GDP.

- Japan, UK, and India each invest 0.8% of their GDP.

- Brazil invests 0.4% of its GDP.

- Germany and Mexico both invest 0.3% of their GDP.

- United States has the lowest investment at 0.2% of GDP.

The bars are colored in shades of blue, with the length of each bar corresponding to the percentage of GDP invested in renewable energy. The percentages are labeled at the end of each bar for clarity. The chart visually emphasizes the variation in investment levels across different countries.

The Potential Wind Energy Resource

The Potential Wind Energy Resource

A quick look at an annually-averaged wind map of the world (below) shows the regions of the world that are best suited for the production of wind energy in colors ranging from yellows to red (where the average winds are at least 9.75 m/s or 20 mph). The offshore regions are clearly the best in terms of the energy potential, but not all of these offshore regions are close to where people live. Even for onshore portions of the world, the wind energy potential does not always coincide with where the people are concentrated. This points to the necessity of new transmission lines to deliver this wind energy to major population centers.

So, just how much energy could be produced by the wind? In 2009, a group of scientists makes some calculations to estimate the potential for the world and the US, using wind data and some assumptions about the size and spacing of the turbines. They assumed 2.5 MW turbines on land, and 3.5 MW turbines offshore, which were big for that time. They assumed that you could only place the turbines in unforested, ice-free, nonmountainous areas away from any towns and that the turbines had to be spaced by several hundred meters so they do not interfere with their neighbors. They further assumed that each turbine generated just 20% of its rated capacity to account for mechanical problems and intermittent winds. What they came up with is summarized in the table below, and it is pretty remarkable. The units here are exajoules (EJ = 1 x 1018 Joules) of energy over the course of a year. For reference, in 2018, the US total energy consumption (not just electrical energy) was 106 EJ and the global consumption was about 600 EJ. So, with just onshore wind energy, the potential is more than twice what we consume in the US, and more than 4 times the global consumption. But getting there is a matter of installing a lot of wind turbines!

| Region | World | Contiguous US |

|---|---|---|

| Onshore | 2484 | 223.2 |

| Offshore 0-20m | 151 | 4.32 |

| Offshore 20-50m | 144 | 7.56 |

| Offshore 50-100m | 270 | 7.92 |

| Total | 3024 | 244.8 |

Now let's consider a more practical question — how much wind energy have we managed to produce, and can we somehow project the past trends into the future? The figure below shows the global history of wind energy (solar is plotted too just for comparison), and you can see that it is growing fast.

The image is a line graph titled "Global Solar and Wind Energy Generation History," depicting the growth in energy generation from solar and wind sources from 1985 to 2020, measured in exajoules (EJ) per year.

- The y-axis represents the energy generated per year in EJ, ranging from 0 to 14 EJ.

- The x-axis represents the years from 1985 to 2020.

Two lines are plotted on the graph:

- Solar energy generation is represented by an orange line. It shows a very gradual increase from 1985, remaining almost flat until around 2005. After 2005, there is a noticeable uptick, with a significant rise starting around 2010, reaching approximately 7 EJ by 2020.

- Wind energy generation is represented by a green line. Similar to solar, wind energy generation starts from a low base in 1985, with minimal growth until around 2000. From 2000 onwards, there is a steep increase, particularly sharp after 2010, reaching around 12 EJ by 2020.

The graph visually demonstrates the exponential growth in both solar and wind energy generation over the years, with wind energy showing a more pronounced increase compared to solar. The data points are marked with small dots along the lines, and a legend in the center of the graph identifies the colors associated with solar (orange) and wind (green).

Both of these curves are growing exponentially, and the history so far suggests a growth of about 25% per year on average. If we assume that they continue to grow in the further following this exponential growth, we can project where we'll be at any time in the future. Below, we see where we might be in the year 2030, just eleven years from now. What you see is that we end up with vast amount of wind energy by 2030 — if it grows at the same rate it has been growing at, we end up with almost 300 EJ per year, about half of the current global energy consumption, and if it grows at a smaller rate of 20% per year, we still end up being able to supply about 20% of the total global energy demand.

The image is a line graph titled "Global Wind Energy Generation History and Projection," which illustrates the historical data and projected growth of global wind energy generation from 1985 to 2030, measured in exajoules (EJ) per year.

- The y-axis represents the energy generated per year in EJ, ranging from 0 to 300 EJ.

- The x-axis represents the years from 1985 to 2030.

The graph features two lines:

- Historical Data (blue line) - This line shows the actual wind energy generation from 1985 to around 2020. The generation starts from nearly 0 EJ in 1985 and shows a gradual increase over the years, with a noticeable acceleration starting around 2005, reaching approximately 15 EJ by 2020.

- Projections - There are two projection lines for future growth:

- 20% per year growth (yellow line) - This projection starts from the point where the historical data ends (around 2020) and shows a steep increase, reaching about 100 EJ by 2030.25% per year growth (orange line) - This projection also starts from the end of the historical data and shows an even steeper increase, reaching around 250 EJ by 2030

The graph visually represents the exponential growth expected in wind energy generation if the growth rates continue at 20% or 25% per year. The lines are color-coded with labels indicating the growth rates, and the overall trend suggests a significant future increase in wind energy generation.

Barriers to Additional Wind Energy Development

Barriers to Additional Wind Energy Development

It is worth noting that, as with solar, wind investments are not always happening in the windiest areas. The reality is that there are a large number of factors that influence the development of wind energy globally. As the technology for wind energy has improved, other factors have also come together to create market drivers for wind power. These drivers include:

- Declining Wind Costs

- Fuel Price Uncertainty

- Federal and State Policies

- Economic Development

- Public Support

- Green Power

- Energy Security

- Carbon Risk

Earth: The Operator's Manual

Earth: The Operator's Manual

Despite all of these barriers to wind energy deployment, wind is, in fact, one of the fastest-growing sources of power generation in the world. Wind energy is being embraced in areas that have traditionally favored low-carbon energy development as well as in areas that have a long history of fossil fuel extraction and use. The following video explains how two very different regions - Denmark and Texas - have embraced wind energy.

Video: Yes, in My Backyard (aka YIMBY!): (9:08)

NARRATOR: Are there other examples of communities and nations that have begun the transition away from fossil fuels? What does it take to welcome the turbines and solar farms of the new energy system, and say, "Yes, In My Backyard." This is the story of two communities that at first look very different. Samso is a small island off the Danish mainland. West Texas is a vast, dry expanse in America's South. What both have is abundant wind. At times, Samso produces more electricity than it uses, exporting surplus power to the Danish mainland. And Texas wind now generates as much power as the next three U.S. states combined. Samso and West Texas both solved the NIMBY, not in my backyard challenge that has stymied so many renewable energy projects. It's not easy, but with patience, and persistence, and the efforts of the right people, it can be done.

SOREN: Okay-- My name is Soren Hermansen, and I am the Director of the Samso Energy Academy. Samso means, in Danish, means the Meeting Island-- when you make a circle around all of Denmark, then Samso is right in the center of the circle.

NARRATOR: Narrator: But it wasn't geography that brought Lykke Friis, then Denmark's Minister of Climate and Energy, here in mid-2011. It was why and how this community had turned NIMBY into "Yes, in my backyard."

LYKKE FRIIS: Well, Samso is a pioneering project, in the sense that Samso, way back, decided that Samso should become independent of fossil fuels. Narrator: Before its transformation, people thought of Samso as just a cute tourist community, busy in summer, empty and desolate in winter. Now people come here not just to see the turbines, but to understand the process that got the community to welcome wind energy. After a national competition, Samso was selected by the Danish government to be a proof of concept for how to transition from fossil fuels. But it was up to individuals like Soren Hermansen, with the passion and skills to effect change, to figure out just how. Soren: So when we won, the normal reaction from most people was, "Yeah, you can do this project, that's OK, but just leave me out of it."

NARRATOR: Samso has a deep attachment to its past and values its traditional way of life.

SOREN: But gradually we won their confidence in establishing easy projects to understand, and also easy projects to finance. Because basically, it's all about, "What's in it for me?" Because it's not convinced idealists or green environmental hippies who lives here.

NARRATOR: Soren, a native of the island, convinced some of his neighbors to become early adopters. They found success and spread the word. Jorgen Tranberg operated a large and profitable herd of milk cows. After initial reservations, he invested in a turbine on his own land. When that went well, Jorgen became part owner of one of the offshore turbines.

SOREN: Farmers, they have to invent new things and be ready for changes. So when they see a potential, they look at it, no matter what it is. They look at it, say, "Could I do this?" And if they see fellow farmers do the same thing, they are quick to respond to that. So even being very traditional and conservative in their heads I think they have this ability of making moves and do things because they have this independency in them. A farmer is a free man-- maybe he owes a lot of money to the bank, but he's still a free man in his thinking.

NARRATOR: It was seeing what was in it for them and for their community, that won over landowners in West Texas. And it took one of their own, a man whose family had deep roots in Roscoe's cotton fields, to educate them about wind farming. Cliff Etheredge: Well, I'm really a farmer-farmer, you see. I farmed for almost over 40 years. We're in-- right in the middle of the Roscoe Wind Farm. And we've got about 780 megawatts of production, that's per hour, enough electricity for about 265,000 average homes. Narrator: Roscoe had no oil and faced hard times in the early '90s, but it did have wind.

CLIFF: When this land was acquired there was absolutely no value to the wind. Fact is, it was a severe detriment, because of the evaporation of the moisture.

NARRATOR: Cliff, like Soren, had to work with his neighbors to get them ready to accept wind turbines.

CLIFF: The first thing farmers want to know is, "Well, how much is it going to cost me?" It costs them nothing. "What's it going to hurt?" Three to five percent of your farmland is all it's going to take up. You can do what you want to with the rest of it. Then it came down to, "Well, how much money is this going to make me?"

NARRATOR: Cliff did his research and checked his numbers with wind experts and the Farm Bureau.

CLIFF: Then I was able to go to our Landowners' Association and show them, where they had been receiving 35 to 40 dollars an acre, then the landowners could expect somewhere in the neighborhood of three times that.

NARRATOR: In fact, farmers stand to make 10 to 15 thousand dollars a year, per turbine, just from leasing the wind rights.

CLIFF: There was no guarantee in it from the very beginning, but sure enough we've got, I think, in the neighborhood of 95 or more percent of our area that accepted the wind farm.

NARRATOR: In both Samso and West Texas, individuals saw economic benefits. But the whole community, beyond the investors and land-owners, benefited too.

CLIFF: Because of the wind farm, now, and the people working in the wind industry, now we've got jobs available and opportunities for young people to come back from college or from technical school or from whatever. It's just been a Godsend.

NARRATOR: For Kim Alexander, superintendent of the Roscoe school district, that godsend translates into dollars.

KIM ALEXANDER: In 2007, prior to the wind values coming on our tax roll, our property values were at about 65 million dollars. And then, that wind development, they jumped to approximately 400 million dollars, to 465 million dollars.

NARRATOR: The school district will get more than 10 million dollars over a decade. That guaranteed revenue stream unlocked additional funding. School buildings, some dating from the 1930s, could be updated, and computer labs added.

CLIFF: This is an indication to me of what can be done for rural areas, and will be done, all the way to Canada-- bringing life and prosperity back to these rural communities that are suffering just like we have.

NARRATOR: The same oil shock that got Brazil started on ethanol, got Denmark started on manufacturing wind turbines, just in time to compensate for a decline in its shipbuilding industry.

LYYKE: And it's also good for the economy, in terms of export. I mean, 10 percent of Danish exports comes from the cleantech area.

NARRATOR: Energy and environment always require tradeoffs, such as clear vistas versus clean energy. It's something that communities have to make time to work through. Cliff, for one, believes it's worth it.

CLIFF: Everything, the schools, the churches, the civic organizations, all the businesses will benefit from this. It will increase, hopefully, our town's populations, and our economics.

KIM ALEXANDER: My granddad used to say, not realizing he was prophetic, but "If we could sell the wind, we'd be wealthy." Well, who would have ever thought we'd be able to sell the wind?

NARRATOR: For Samso, Denmark, and Texas, clean energy brought economic benefits and energy security. But replacing fossil fuel emissions with wind power has other advantages.

LYKKE: And let's not forget, also good for climate and health, and such, and that's a very important argument.

CLIFF: We've got a constant wind resource here, that's tremendously valuable, and as opposed to oil and gas, it'll last forever, and it doesn't pollute anything.

We have already mentioned the US Production Tax Credit, which is responsible for a good amount of the trend in US wind energy investment – both up and down! A decline in wind investment in 2010 and 2011 was due in part to the global financial crisis. A drop in natural gas/wholesale electricity prices has made some planned projects less competitive than originally expected and halted development. There has also been a slump in the overall demand for energy. Another factor that limits the growth of wind power capacity is the constraint on the transmission infrastructure. As can be seen in the wind capacity map on the previous page, many of the locations that experience the windiest conditions are not close to coastal population centers. The cost of upgrading this infrastructure is significant — perhaps $30 to $90 billion in the US by the year 2030 according to some estimates. This seems like a huge amount, but consider that our government spends about \$20 billion each year in direct subsidies to the fossil fuel industry, which would sum up to \$200 billion by the year 2030. In light of that, the upgrade cost for better transmission lines is a bargain!

Note

A great resource for information on the current state of the US wind market and the wind industry, in general, is the US Wind Technologies Market Report [32]which is annually published by the Mark Bolinger and Ryan Wiser of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Discussion Assignment

Reminder!

After completing your Discussion Assignment, don't forget to take the Module 6 Quiz. If you didn't answer the Learning Checkpoint questions, take a few minutes to complete them now. They will help your study for the quiz and you may even see a few of those question on the quiz!Discussion Question

Objective: