Lessons

This is the course outline.

Unit 1: Fresh Water: Scarcity or Surfeit?

Unit 1: Fresh Water: Scarcity or Surfeit?

Overview

Water is often called the “Elixir of Life.” We refer to Earth as the “Blue Planet” because of its abundance of liquid water; indeed, NASA’s search for life on other planets starts with the search for water. While its importance for sustaining life is perhaps common knowledge, the extent to which we depend on water in every aspect of our everyday lives and activities is less obvious. In this course, we will explore these facets of water’s impact on human society. We begin with an overview and discussion of the underpinnings of water use, occurrence, and movement. We then explore the many and profound consequences of human manipulation of water; the ability to reroute, store and transport water is one of the very things that has allowed human civilizations to thrive, yet has also led directly to a complex and broad-ranging relationship with this most essential of substances. Water pervades almost every aspect of our existence, including food production; the manufacture of goods and development of new technologies; transportation and energy generation; human health via its use for sanitation, the conveyance of waste, and control on the distribution of water-borne diseases; and the sustenance of ecosystems on which we often depend but do not realize. Not only is water needed for you to be here and to produce your breakfast this morning, but the computer you are using to read this course’s modules, the electricity needed to turn on your computer, the steel and fuel needed to transport you to/from school all required even more water!

Through its importance in these areas, it is perhaps unsurprising that water allocation and policy lie at the heart of economic and political tensions between communities, states, and nations. As populations in many water-stressed areas continue to grow, and in the face of climate changes that affect where and when water may be available in the future, these challenges continue to mount.

We begin this course by providing an outline of water resources on a global basis—where resources are abundant or limited and why. We first ask questions regarding the "value" of water and consider whether having access to fresh (uncontaminated) water for drinking and other household uses is a fundamental right as opposed to water being a commodity subject to profit-taking. In other words, is water a resource that is subject to privatizations and price fluctuations, or should water be provided by benevolent governments at a reasonable cost? In addition, we are concerned with projected population growth, its regional distribution, and resulting demands for water in the future. This helps us appreciate the two-way relationship between water and human society: how water availability and quality affect economic opportunities and human well-being, and how human activity affects water resources.

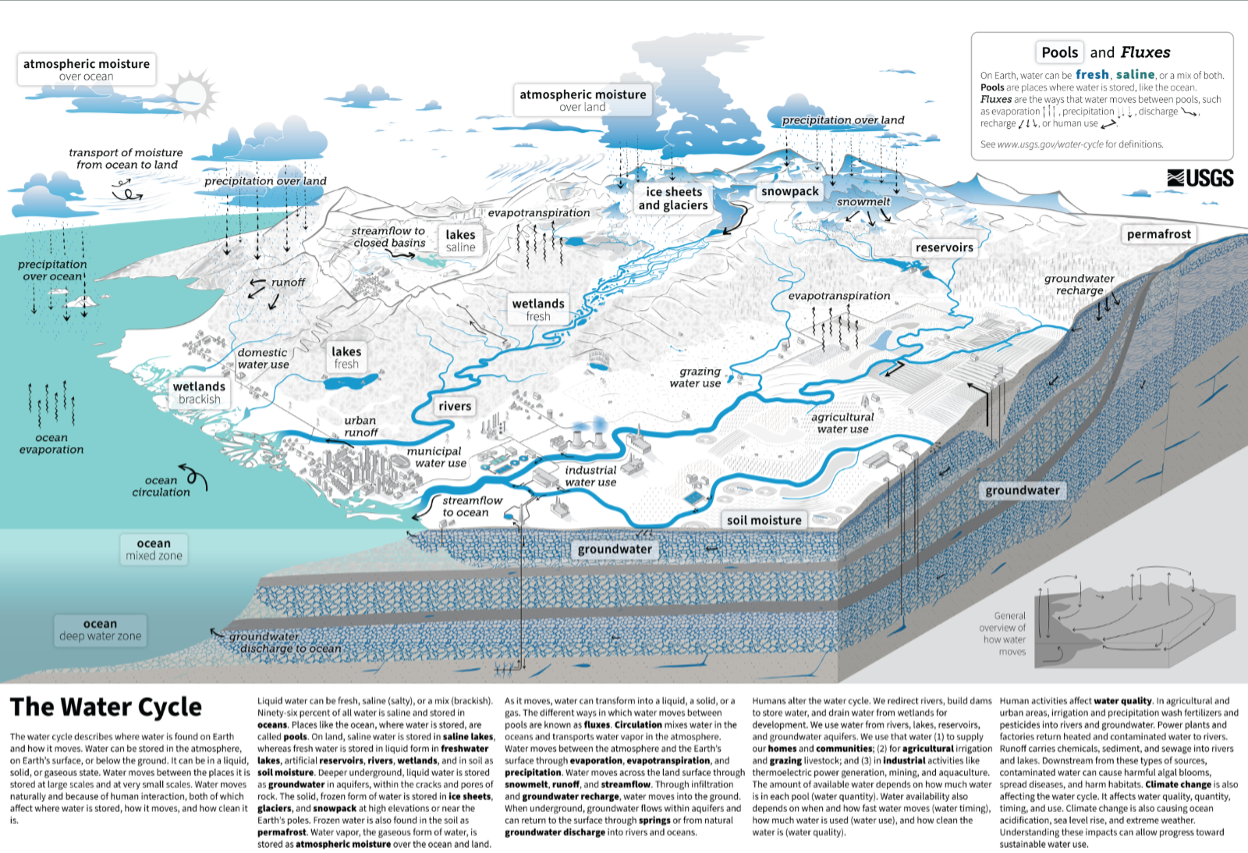

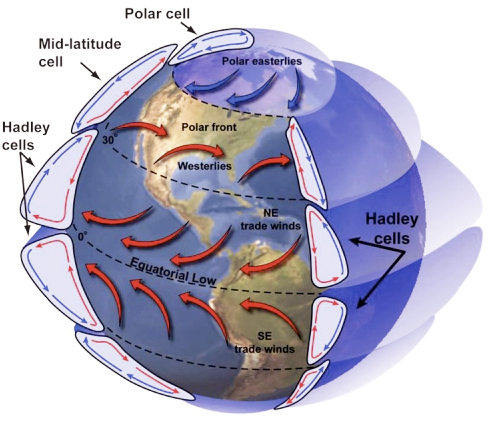

A major consideration is why some regions have a surplus of water and others have less than necessary to support local populations in various activities. In order to understand this, we need to examine the operation of Earth's climate system in some detail: the roles of global wind systems, proximity to an ocean, and topographic features (especially mountain belts) in determining patterns of rainfall, a first-order control on water availability. This involves discussion of the global "hydrologic cycle" that reflects the cycling of water from the ocean to atmosphere to land and its ultimate return to the sea. We also outline some of the important properties of water that determine its behavior in the climate system, flowing water, and sustaining life.

Modules

Unit Goals

Upon completion of Unit 1 students will be able to:

- Describe the two-way relationship between water resources and human society

- Explain the distribution and dynamics of water at the surface and in the subsurface of the Earth

- Interpret graphical representations of scientific data

- Identify strategies and best practices to decrease water stress and increase water quality

- Communicate scientific information in terms that can be understood by the general public

- Predict how the availability of and demand for water resources is expected to change over the next 50 years

Unit Objectives

In order to reach these goals, the instructors have established the following learning objectives for student learning. In working through the modules within Unit 1 students will be able to:

- List the primary reasons that most population centers developed near major rivers or other surface water bodies.

- Provide examples of consumptive and non-consumptive, and direct and indirect water uses.

- Compare the amounts used by the various end-users of water, both in the U.S. and globally.

- Identify regions of critical water stress at present and those anticipated 20 and 40 years into the future.

- Identify possible solutions to anticipated water shortages.

- Discuss issues surrounding the debate about public access to (clean) freshwater.

- Identify the unique physical properties of water that contribute to its fundamental role in driving Earth Systems.

- Quantitatively compare fluxes of water in the hydrologic cycle.

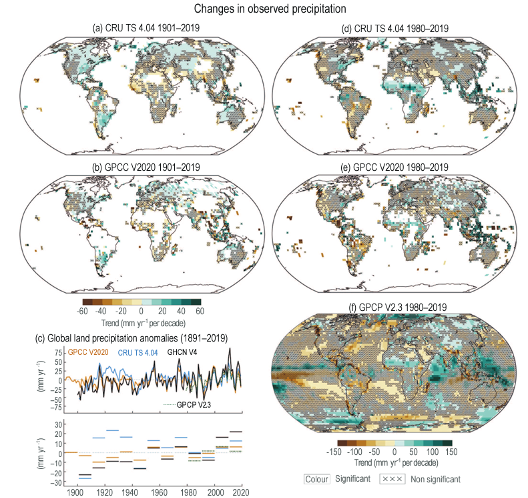

- Assess the relationship between precipitation, topography, and location in the U.S. and globally.

Module 1: Freshwater Resources - A Global Perspective

Module 1: Freshwater Resources - A Global Perspective

While only just beginning this course, you likely already appreciate that water is a precious commodity. For example, a human can survive at least three weeks without food, but can go only about three days without drinking water (or water-based liquid) before dehydration becomes a medical emergency (see the U.S. National Library of Medicines article, Water in Diet [3]. Nonetheless, in the U.S., we commonly take access to quality drinking water for granted, not to mention the availability of water for all other important activities including the production of food and energy. And, this water presently comes to most people in the U.S. at a very low cost—just cents per gallon. We are, of course, privileged relative to other regions of the world, some of which do not have sufficient fresh water resources and where people may not even have access to safe drinking water supplies.

In this module, we will examine the distribution of freshwater resources, the major uses of water, and present and anticipated future demand for water, globally, as the human population increases. We will explore the question as to whether water has a value greater than presently appreciated and whether it will always be readily available to us. For example, you may already know that the western U.S. is experiencing a severe shortage of water as the result of prolonged drought in that region. Is this an anomaly, or might we expect longer-term shortages there and elsewhere in the U.S. and globally as the result of climate change?

Goals and Objectives

Goals and Objectives

Goals

- Describe the two-way relationship between water resources and human society

- Explain the distribution and dynamics of water at the surface and in the subsurface of the Earth

- Communicate scientific information in terms that can be understood by the general public

- Interpret graphical representations of scientific data

- Identify strategies and best practices to decrease water stress and increase water quality

- Predict how availability of and demand for water resources is expected to change over the next 50 years

Learning Objectives

In completing this module, you will:

- Analyze the relationship between land use and access to fresh water

- Calculate the population that can be supported by a finite water source

- Evaluate possible solutions to anticipated water shortages

- Evaluate whether access to clean water is a basic human right, or if it should be treated as a commodity

- Distinguish between direct and indirect water use

- Record and analyze your own personal water usage

- Compare your own personal water use habits with those of your peers and others worldwide

The Value of Water

The Value of Water

Does water have value?

Water is essential to life – both as a basic human need for survival and as an “ingredient” in almost everything we do, from food production to manufacturing to power generation. As we will explore in more detail in Module 2 next week, precipitation and evaporation – and thus water availability – are unevenly distributed around the globe (Figure 1). This also varies seasonally. Figure 1 shows the average global distribution of precipitation for January; to see an animation over the course of the year, check this out:

There are obviously some areas of the world that are wetter than others, and these patterns are persistent throughout the year (i.e. the deserts of the American southwest, Northern Africa, and Western Australia are perennially dry; whereas equatorial central America, Africa, and Indonesia are wet). This uneven distribution of water resources lies at the root of many topics we’ll cover in this course, because it is a primary driver of human activity, ranging from population dynamics to types and locations of particular industries, to power generation, to politics. For example, take a look at the maps in Figures 1 and 2. Are there areas of the world that are persistently wetter or drier than others?

Activate Your Learning

1. List 3 areas/regions that are persistently dry based on the animated map shown above.

2. List 3 areas/regions that are persistently wet.

3. Inspect the freshwater availability map shown in Figure 2. Provide 2 examples of areas of water scarcity that “map” to areas where precipitation is low.

4. Identify 2 areas that are characterized by low precipitation, but apparently are not faced with severe water scarcity. Provide a hypothesis as to why you think this is the case.

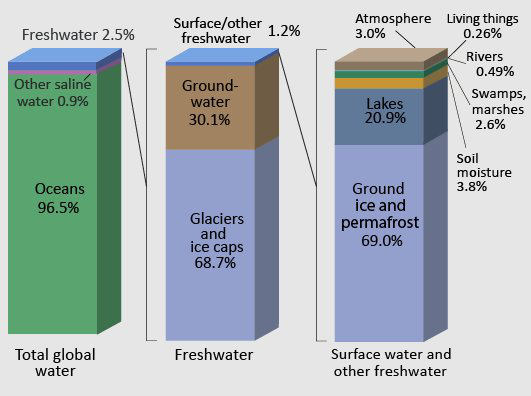

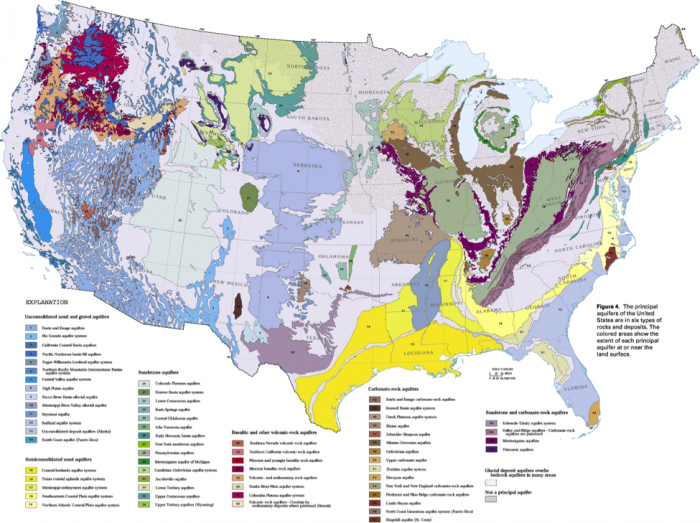

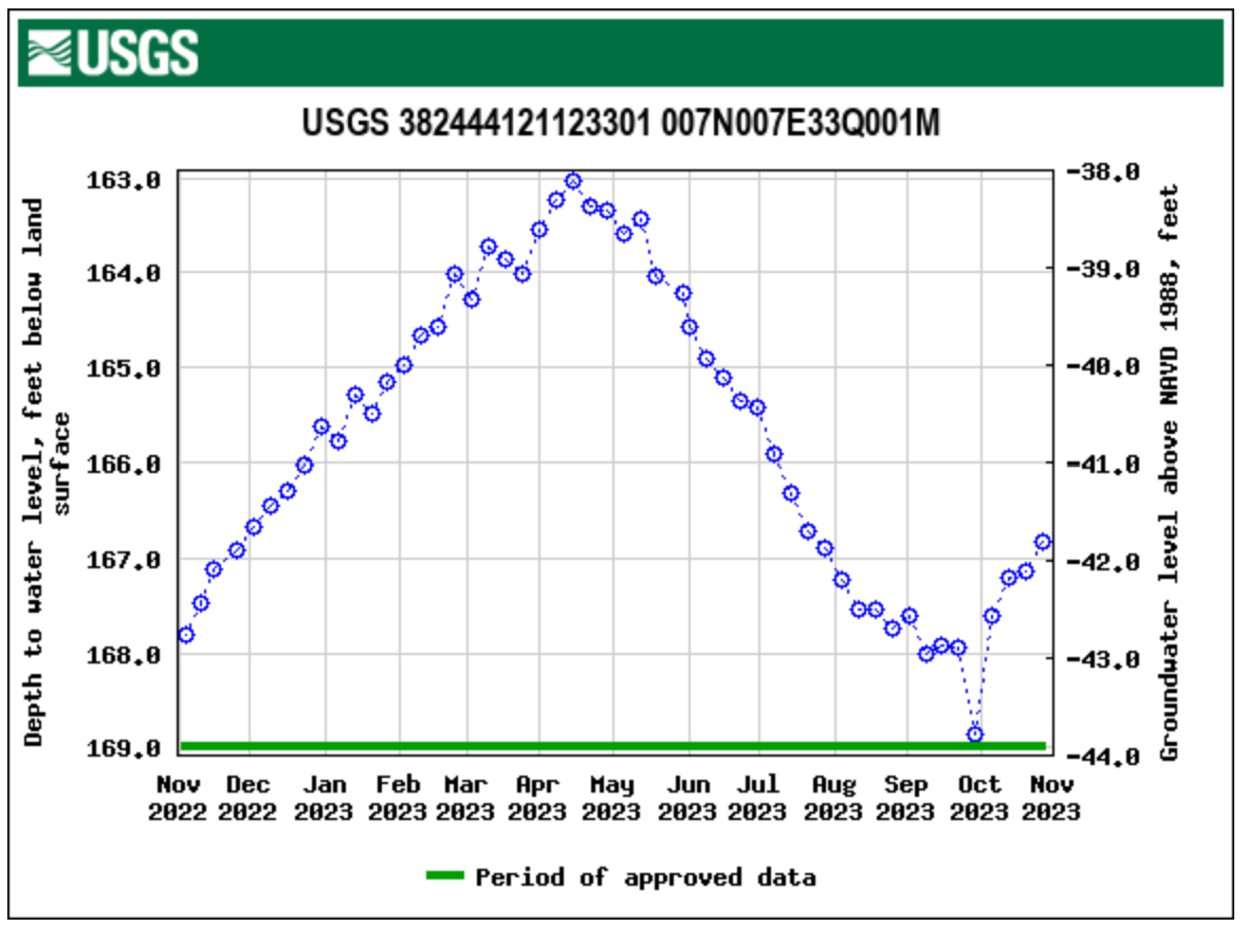

As we’ll see in Module 2, water is transported around the Earth by the hydrologic cycle, in which solar energy drives evaporation of water from the oceans and land surface. This water condenses in the atmosphere to form clouds and eventually to fall as precipitation. Much of that precipitation flows as surface water in rivers and streams. Some of it also infiltrates or percolates into the soil and rock, and becomes groundwater. Surface water constitutes the primary source of water for human activity – it is relatively clean, easy to obtain and move, and constantly replenished (barring prolonged dry periods; as we will discuss in Modules 4 and 8-9). Groundwater constitutes another important source of water for human activity. Although the total volume of groundwater held in fractures and pore spaces in the subsurface is large, it is replenished and flows under natural conditions far more slowly than surface water. Additional energy is required to extract groundwater, because it must be pumped from the subsurface, in some cases hundreds of feet or more. For these reasons, groundwater is generally a secondary source of water, in cases where surface water is not readily available or cannot fully meet demand.

Food for Thought

List at least 2 problems or issues (these can be political, economic, health-related, etc…) that might arise from the unequal geographic distribution of water resources.

Global Freshwater Resources

Global Freshwater Resources

Water use and treatment

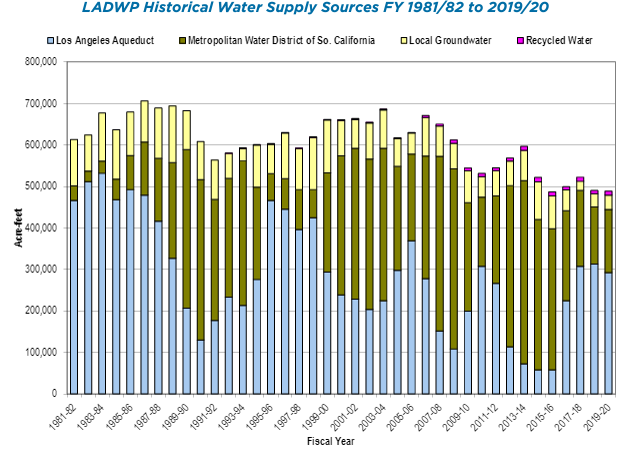

Once taken for human use, water generally follows a path described in Figure 3 below. After undergoing treatment and distribution, it is used. In the broadest sense, water is constantly being re-used. Water that is taken from rivers or streams for domestic, industrial, or agricultural use was most likely also used by communities or farms up-stream, and subsequently treated and discharged. Over even longer timescales, the water in streams, lakes, and groundwater is the same water that has ever been on Earth – and those same molecules have undoubtedly cycled through many plants and animals before we were even around!

Depending on the nature of water use, it may be re-captured after treatment (“recycled water”) for re-use. As we will see later in the semester, this re-use of water resources is one strategy to cope with water scarcity. The recycled water, depending on its quality, can be used for irrigation (i.e. for parks or golf courses), or for domestic supply. Once the water leaves the “use” loop, it is treated and discharged, typically into surface water bodies. In some cases, the treated water may be used to recharge aquifers instead, either through induced recharge systems or at a smaller scale via passive filtration through soils – for example in leachfields. The discharged water, after mixing with water in the river, stream (or aquifer), becomes a water source for downstream or down-gradient users.

Activate Your Learning

1. Do you know the source of domestic or municipal water in your hometown? If yes, what and where is it? If no, does it surprise you to realize that you don't know where your drinking water comes from?

2. Do you suppose that any of that water is used and then treated by others before being taken for your use?

3. Take a look at figure 3 above. Had you thought about your water as a substance that has a “life cycle” and is constantly being used, treated, released, and re-used? If not, does the idea make you uncomfortable?

Water and Population Centers

Water and Population Centers

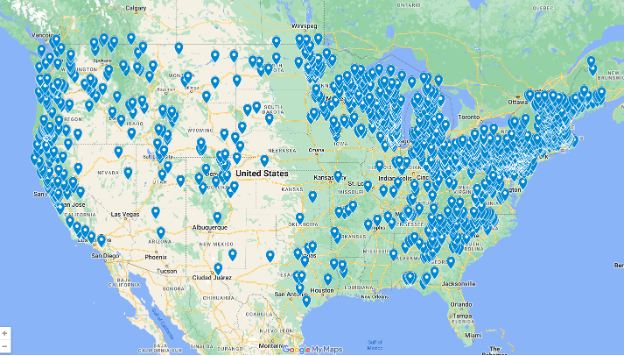

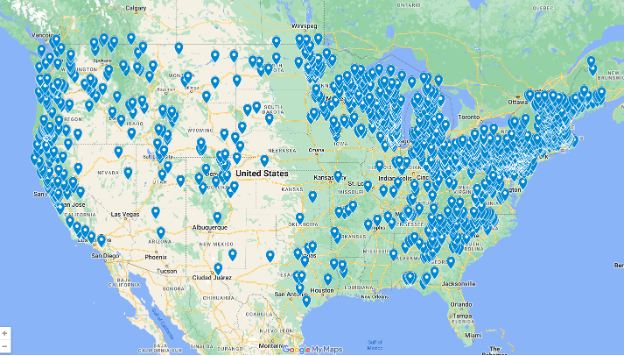

Some cities are sited in areas where water is available - or was at the time they were settled - including Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Chicago, St. Louis, and Pittsburgh (Figure 4). In some cases, and as we will discuss in detail in later modules in the course, rapid development and growing demand can outpace the original and limited water source for a city or region, leading to a vicious cycle of water acquisition, growth enabled by water availability, and subsequent water stress.

Many of America’s major manufacturing centers (i.e. the rust belt) are located in areas where major rivers and canals provided a means for transport of raw materials and goods, power generation, water supply for processing and cooling, and conveyance of waste. At small scale, harnessing hydropower was accomplished by mills; at larger scales in modern dams, it is through hydroelectric power generation. Major rivers also provide the water supply for irrigation-based agriculture in some areas, where precipitation is not sufficient or consistent enough to support crops.

Indeed, for these reasons, rivers in many parts of the world are considered the “lifeblood” of society (Figure 6). For example, the Nile River valley in Egypt comprises ~5% of the land area, yet is home to nearly the entire population of 78 million, with a population density among the highest in the world (more than 1000 people per square km). Despite the obvious connection between water availability and human needs, the story of water resource distribution and population growth is not that simple! In some cases, major engineering projects in which millions of acre-feet of water are moved across states or continents have allowed cities and irrigated agricultural regions to flourish in water-scarce parts of the world. In others, major dams or new water sources (i.e. deep groundwater, reclaimed water, or desalination) have provided a means for cities to prosper in unlikely places. For example, take another look at Figure 4 above. The concentration of nighttime lights provides a reasonable proxy for population density. In many parts of the U.S., they follow the water: along the St. Lawrence, girdling the Great Lakes, and along the Mississippi River. Yet other major population centers have sprung up in perennially dry regions, mainly in the deserts of the southwest: Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Tucson, and Albuquerque.

Learning Checkpoints

1. Inspect Figures 4 and 5 and compare the two maps. Note 3 major cities that are near large water sources (rivers or lakes). View Figures 4 and 5above.

2. List 3 cities or regions of high population density that are not near major water sources, and/or lie in areas of low precipitation.

3. Do you know anyone who lives in one of these dry areas, or have you thought about moving there?

Water Quality and Human Health

Water Quality and Human Health

The distribution of water-rich and water-poor regions is of course not the whole story – access to clean water isn’t just about the amount of water that falls as precipitation. It’s also about the infrastructure needed to obtain, treat, transport, and deliver potable water. And that’s just the water supply. Disposal and sanitation of dirty water are equally important and require a means of transporting waste away from the distributed sources, collecting it and treating it, and discharging it safely. Ideally, both supply and waste conveyance systems should also be monitored for performance and for their impacts on water quality.

In some areas, water is plentiful, but access to clean water is not (Figures 7-8). The converse is also true, mainly in developed nations where water projects, desalination, or dams provide a water supply to regions that receive little precipitation. There is also a clear distinction between access to clean water in rural and urban areas (Figure 7), wherein access in rural areas, even in developed nations, lags behind that in urban areas.

| Year | Status | Water Supply | Improved Sanitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | World | 95% | 79% |

| 1990 | Developing | 92% | 61% |

| 2004 | World | 96% | 80% |

| 2004 | Developing | 91% | 70% |

| Year | Status | Water Supply | Improved Sanitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | World | 63% | 26% |

| 1990 | Developing | 61% | 19% |

| 2004 | World | 72% | 39% |

| 2004 | Developing | 70% | 35% |

Learning Checkpoint

1. What is the primary trend shown in Figure 7 above, with respect to urban vs. rural areas?

2. Is there a major difference in access to clean water supply and sanitation when comparing developed and developing nations?

3. Which is the bigger difference – urban vs. rural, or developed vs. developing nations?

4. Do you find your answer to question #3 surprising – or is it what you had expected?

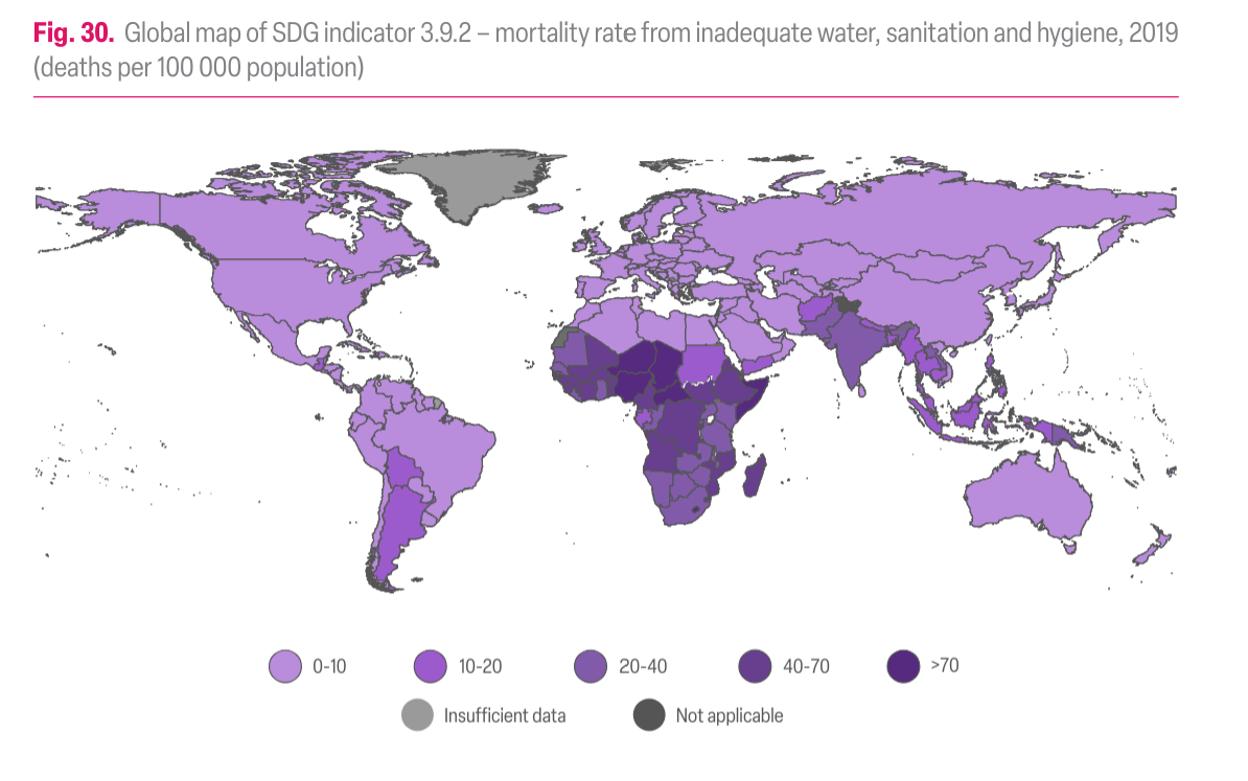

Access to clean water differs between rural and urban areas, and between developed and developing nations. In general, in rural areas, even in developed nations, access to water and sanitation lags behind that in urban areas. Globally, the areas with the poorest access to clean drinking water are in equatorial and sub-Saharan Africa, and parts of South America and southeast Asia (Figure 8).

One might imagine that access to clean water and sanitation would be strongly correlated with water-related illnesses and death. For example, compare the maps in Figures 8 and 9.

Learning Checkpoint

1. Compare the maps in Figures 8 and 9. Is there a correlation between access to improved water and water-related illness? Note two areas where there is a correlation, either positive or negative. See Figures 8 and 9 above.

2. Based on Figure 8 and the distribution of water availability, do you think that these problems are related to water scarcity, or more related to water treatment and infrastructure?

Water Usage: What and Where?

Water Usage: What and Where?

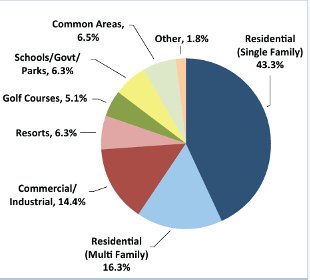

How much water do we use, and for what? Water “permeates” almost every aspect of our lives (no pun intended!). Some uses of water are obvious – for example, municipal and domestic supply used for drinking, cleaning, flushing and watering. Others are less obvious, such as water used for irrigation to grow produce, grains, or feed. The water needed to raise livestock is one step further removed, since the water “used” to produce the product includes the water that must go into growing feed. Yet other uses of water are even less visible, for example for refining fuels, cooling for thermo-electric power generation, and the manufacturing of almost everything in our day-to-day lives.;

Because the types and scales of water use vary widely – from domestic wells that pump at a few gallons per minute, to allocations of major rivers in billions of gallons, the units of measurement used for water management also span an enormous range (see Units).

Water Use

Water Use

How much and for what purposes?

Globally, there is a widely varied usage of water, as a result of differing total populations and population densities, geography and climate (i.e. water availability), cultures, economies, lifestyles, and water use and reuse efficiency. This can be described both in terms of total water abstraction from surface water and groundwater sources and as per capita water withdrawal. It can also be divided to consider the end uses (for example, as percentages of the total use), or to consider the source of the water. Each of these facets of water use illuminates different aspects of the “water story”.

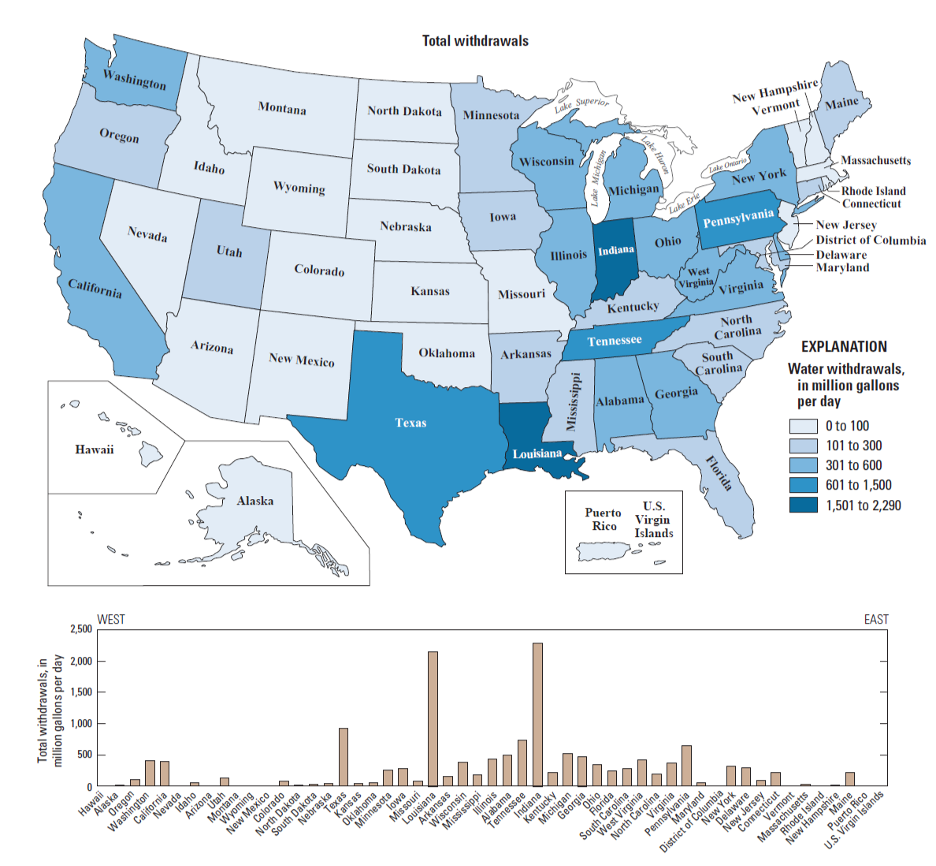

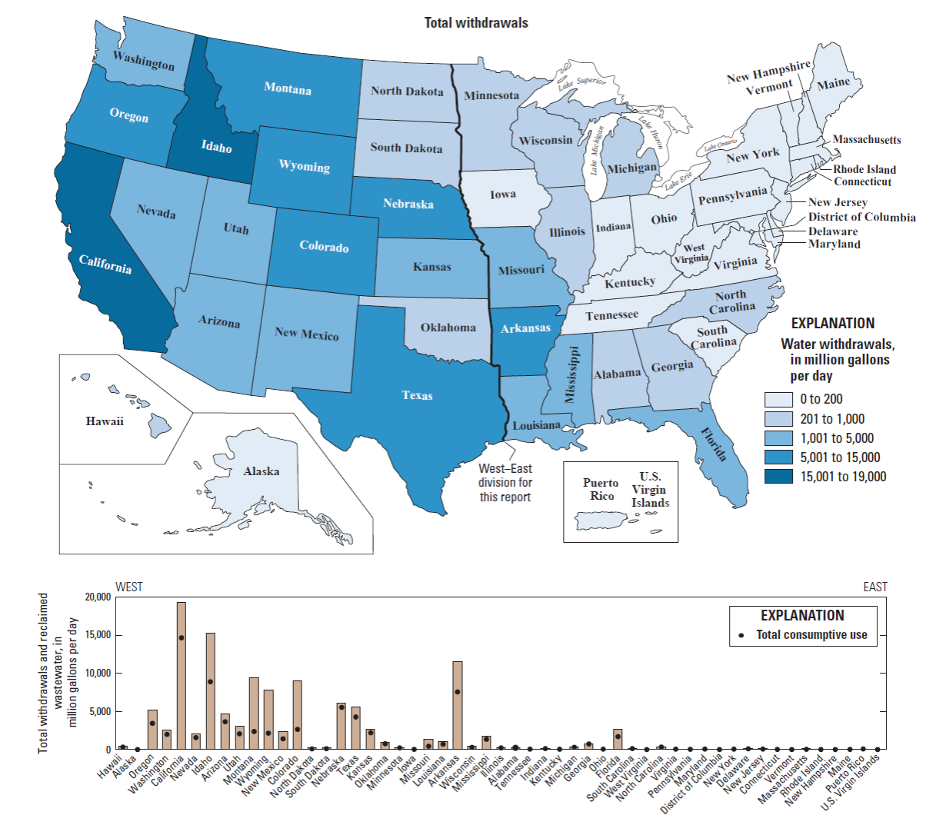

In many industrialized nations, the dominant water uses are for industry (including thermoelectric power generation, manufacturing, etc…) and agriculture (Figures 10-11). In contrast, domestic and municipal water use generally constitutes less than 15-30% of the total. In developing nations, this is somewhat different – total water use is smaller, less is used for industry, and the proportion used for domestic water supply is larger.

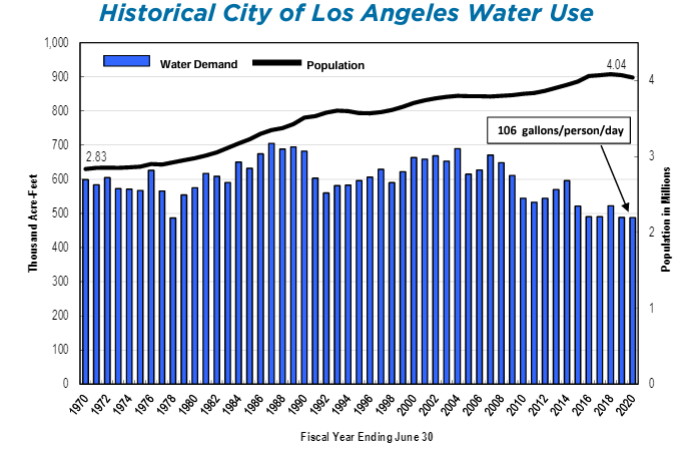

In the U.S., the average per capita use of domestic or municipal water (i.e. the most direct uses – those that would be measured by the water meter at your home) is about 215 m3 per person per year, equivalent to 156 gallons per day (as of 2002). For comparison, the total abstraction of water from surface and groundwater sources in the U.S. is about 1700 m3/person/yr, or 1230 gallons per day. The difference in these numbers represents the large proportion of water that goes to so-called “indirect” uses: food production, manufacturing, power generation, and mining, among others.

In contrast, in sub-Saharan Africa, total water use is less than 200 m3 per person per year (less than 12% of water use in the U.S.). Total abstractions in Western Europe are about 600 m3 per person per year, about 850 m3 per person per year in the Middle East; and 1150 m3 per person per year in Australia. Among those nations with the highest water use, agriculture accounts for anywhere from <40% of use (U.S.), to 67-81% (India and China), to as much as 96% (Pakistan). Industrial use (including power generation) ranges from over 80% of total water use to less 1%. In the U.S. water use for power generation is near 50%; in China, it constitutes 25% and in India about 5%. Germany, Russia, Canada, France, and much of Western Europe use around 60% of withdrawn water for power generation. Municipal and domestic water use typically constitutes about 10-20% of the total and varies little among the worlds most populous countries (Figure 9). You can explore these patterns on your own via a useful interactive plotting engine at Gapminder. [11]

It is important to note that because many products are imported or exported across state and national borders, the total abstractions of water in a given place do not necessarily map to the distribution of water “consumption” there. Consider tomatoes that are transported from California to Massachusetts. The water withdrawal from rivers and aquifers needed to grow the tomatoes would appear on California’s “water tab”, but the eventual use of that water would be elsewhere. The same goes for agricultural and industrial products exported internationally. This flow of indirectly used water, embedded in products, is termed virtual water, and is defined as the amount of water used in generation of the product, or alternatively, the amount of water that would be needed to generate the product at the site where it is ultimately used. It is “virtual” because the water use is indirect; it is required to make or grow the item but is not actually physically contained in the item or transported with it.

Consumptive vs. Non-consumptive Use

Another important aspect of water use is the degree to which the water is available for recycling and/or reuse (Figure 12; cf. Figure 2). For some water uses, including industrial or domestic applications, the wastewater is captured, treated, and may be reused. These are termed nonconsumptive uses. For example, water used in homes is, for the most part, recaptured for treatment and discharged to surface water or groundwater systems – or for recycling of supply. In this sense, the water is not removed from the system (i.e. not “consumed”). In other applications, the water is effectively removed from the Earth’s surface environment and is not available to be re-captured. These are consumptive uses. Examples include water used for agriculture, which is mostly transpired by plants or evaporated and thus transferred to the atmosphere, or thermoelectric power generation, in which much of the water also evaporates (think of the steam you may have seen rising from power plants – this is consumptive water use, in action!).

Learning Checkpoint

1. Describe the difference between consumptive and non-consumptive water use. Provide an example of each.

ANSWER: Consumptive use means that the water cannot be recovered, usually because it is lost to evaporation or transpiration, or to deep aquifers. Examples include irrigation, lawn watering, and some fraction of the water used for fracking or cooling in thermoelectric power generation. Non-consumptive use implies that the water may be recovered and treated for reuse either by the same users or by downstream users. Examples include many industrial uses and domestic use.

Click here for a text description

| Usage | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Public supply | 11 |

| Domestic | 1 |

| Irrigation | 31 |

| Livestock | Less than 1 |

| Aquaculture | 2 |

| Industrial | 4 |

| Mining | 1 |

| Thermoelectric power | 49 |

Click here for a text description

Click here to expand for a text description of Figure 13

Learning Checkpoint

1. Based on Figures 10-13, what are the two largest uses of water in the U.S.?

ANSWER: Irrigation (agriculture) and thermoelectric power generation.

2. Have the dominant uses of water in the US changed much in the past 50 years? If so, how?

ANSWER: Yes, they have. Prior to around 1965, irrigation was the largest use of water in the US. From then to the present, thermo-electric power generation has overtaken it, although the amount of water used for both applications has grown.

3. Note three regions or countries where the dominant water use is for agriculture (look at Figure 12). Note three where it is for industry. Is this what you would have expected?

ANSWER: Agriculture: mainly in equatorial regions of Africa, Asia, Indonesia, and S. America (dark green in the top panel of Figure 12). Industry: mainly in N. America, Europe, and Russia (pink and red areas in the center panel).

4. How much water do you think you use per day for household or domestic activities (e.g., washing dishes, laundry, showering, cooking, drinking)?

ANSWER: Most people underestimate their use and guess 20-50 gallons per day.

Supply and Use on Multiple Scales: Units of Water

Supply and Use on Multiple Scales: Units of Water

Units of measurement: volumes, fluxes, and concentrations

The uses of water for human activity vary immensely, and as a result, water resource management covers a wide range of temporal and spatial scales. In some cases, the timescales are short and volumes relatively small (i.e. domestic pumping of several gallons per minute, over timescales of minutes or hours). At the other extreme, water allocations for states or municipalities are often considered in the context of average annual flows in the billions of gallons. Because so many different scales of measurement are used to describe water flux or discharge (volumes of water) and flow rates (the velocity of flow), it is important to have some facility with the various units of measurement and get a sense for their relative magnitudes.

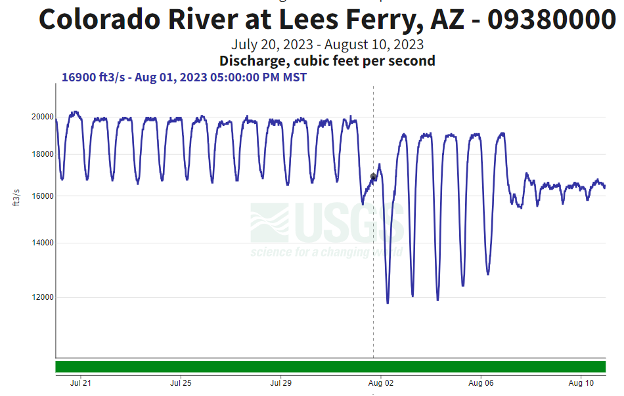

As one example, the total fluxes of water through river systems – commonly used to define allocations of water for states or nations - are measured and reported in acre-feet. This is a unit of water volume equal to the amount of water that covers an area of one acre, one foot deep. One acre-foot is equivalent to 325,851 gallons (see summary of unit conversions from the U.S. Geological Survey [14]), and is often considered as the amount of water needed for a family of four for about one year.

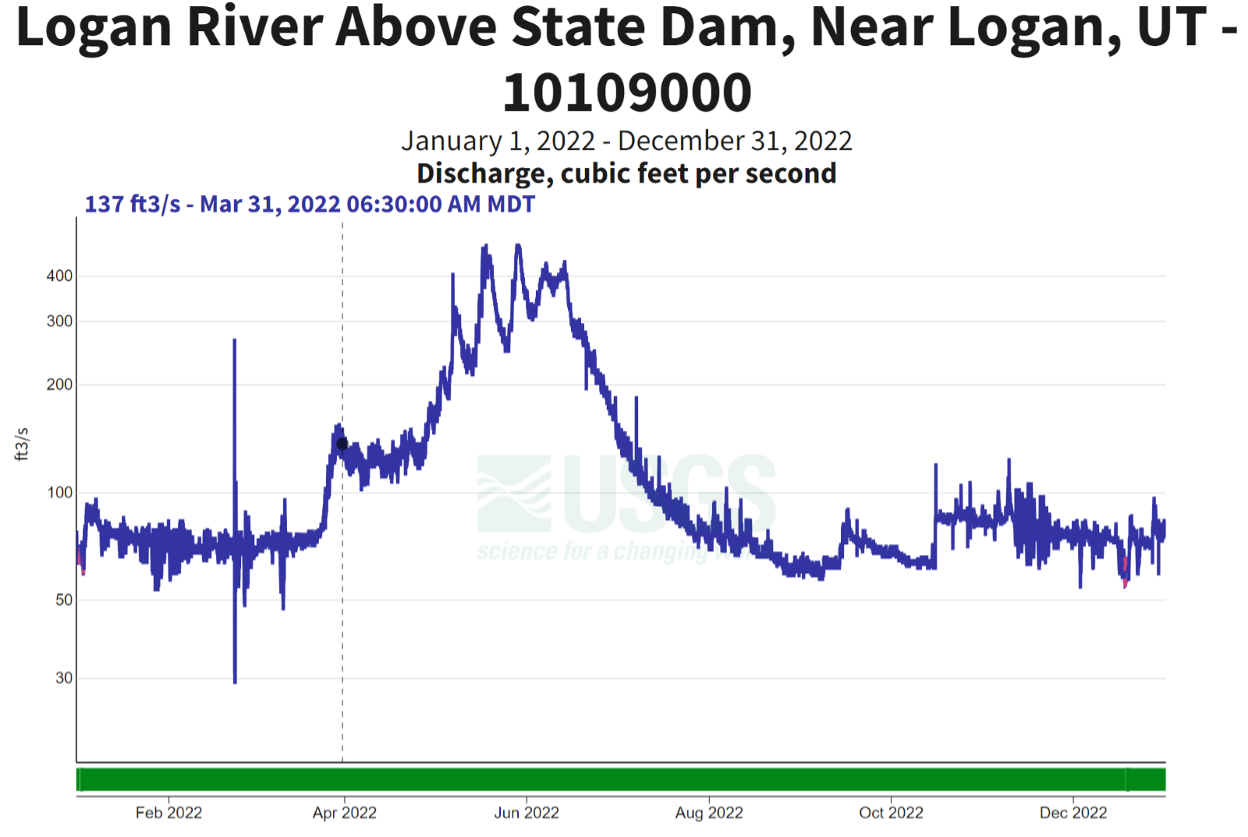

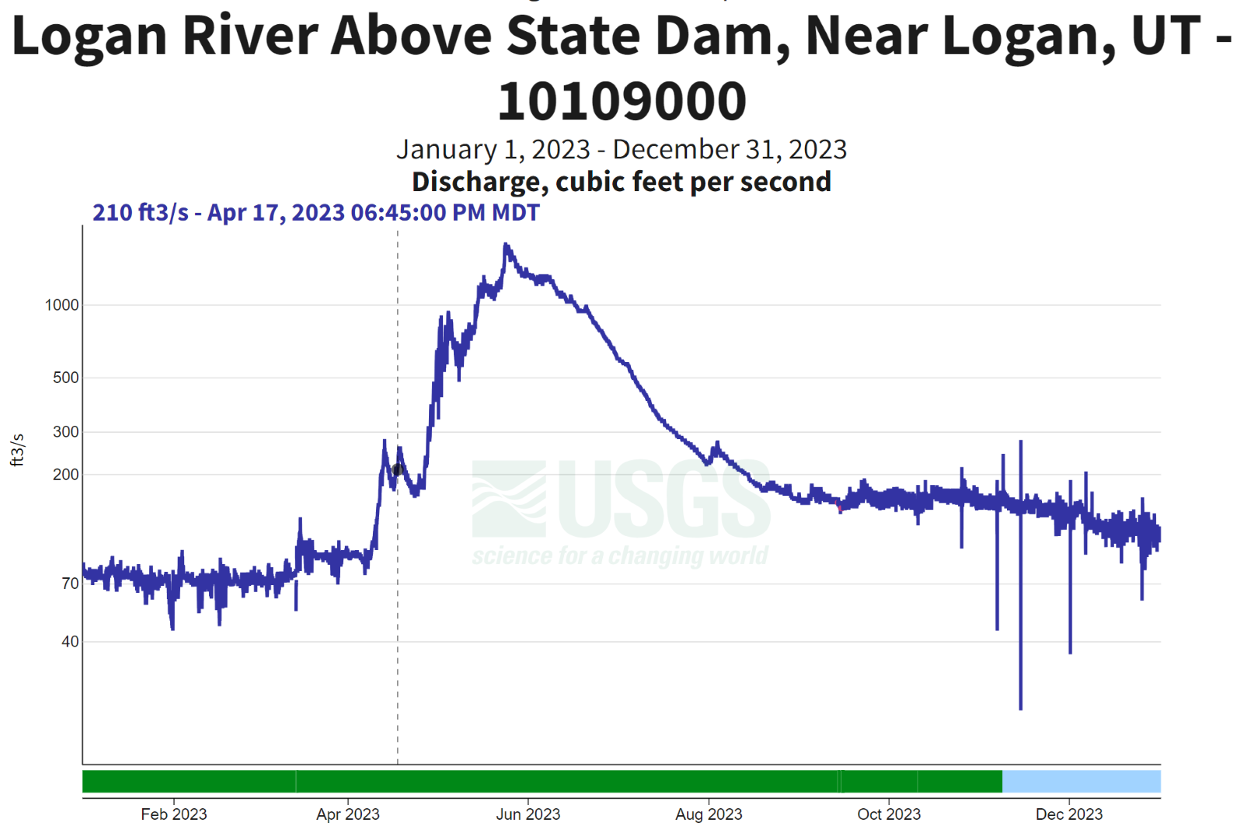

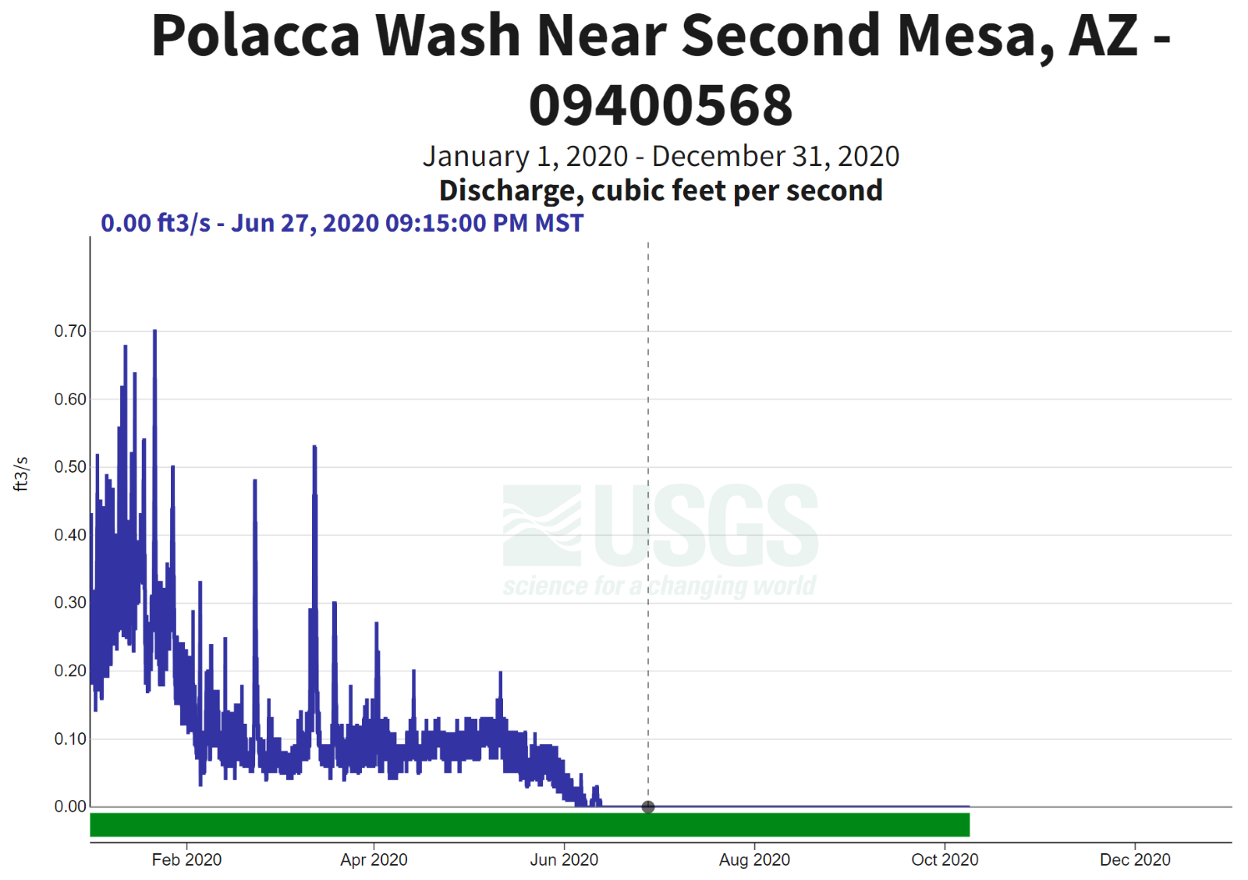

As we’ll discuss in Module 3, over shorter timescales, river discharges are reported in units of cubic feet per second (cfs), cubic meters per second (m3/s), or gallons per minute (gpm). As one example, on average, Spring Creek carries about 50 cfs at Houserville, PA; this increases downstream to about 90-100 cfs at Axemann as the creek is fed by springs and small tributaries. Short-lived peak discharge may exceed 500 cfs after storm events. For comparison, the flow of the Mississippi River at St. Louis, MO is typically about 400,000-600,000 cfs; in major floods the discharge is over 1,000,000 cfs. The flow rates of rivers and groundwater, as we will see in Modules 3-4 and 6, are reported as a velocity - units of length per time. These measures represent the velocity of the water itself, or of an object (stick, boat, person, etc…) carried by the river or stream.

Yet other key quantities in hydrology are reported in units of an equivalent depth (or length) per time. For example, rainfall rates are described in units of inches, cm, or mm per hour (for individual storm events) or per year (i.e. annual average precipitation). Evaporation rates are reported in the same way – but of course, represent water transport in the opposite direction (up!). The total volume of water these represent depends on the area over which they occur.

The Geographic Distribution of Water Uses

The Geographic Distribution of Water Uses

A deeper look: the geographic distribution of water uses

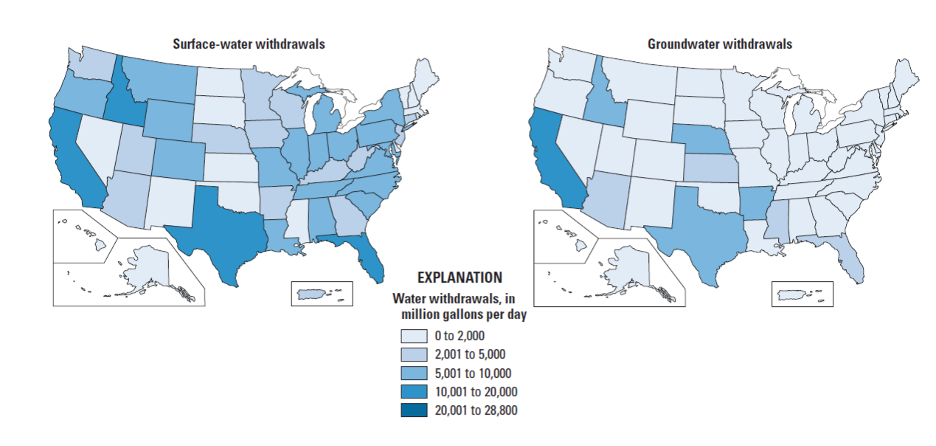

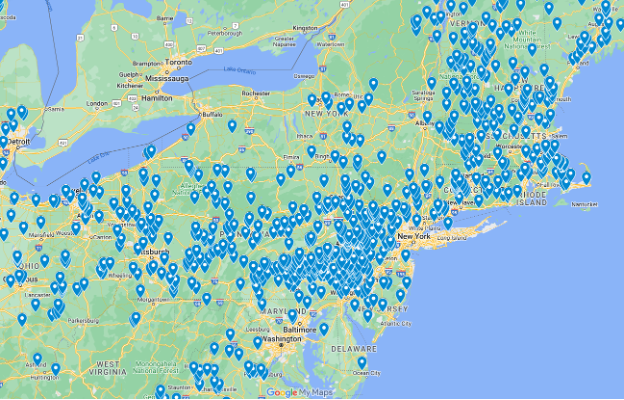

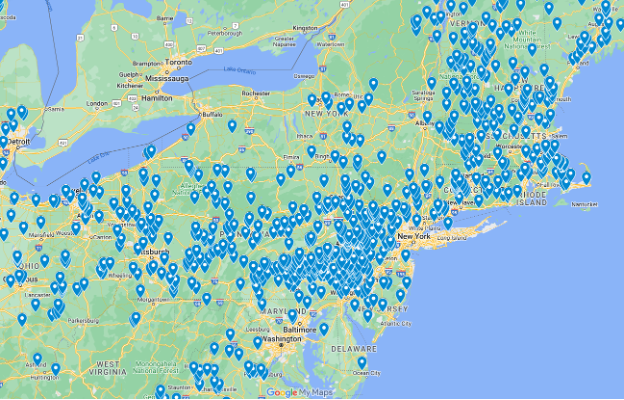

It is also instructive to look in more detail at the distribution of different water uses. For example, in the U.S., industry is concentrated East of the Mississippi, mainly in the “steel belt” (also known as the “rust belt”) and in Texas and Louisiana (primarily related to oil and gas extraction) – and thus water use for industry is as well (Figure 14). It’s worth considering whether this pattern is ultimately rooted in the timing of settlement and westward expansion in the U.S., availability of fuel (i.e. coal), or availability of water sources and rivers as a means of transportation for goods and raw materials. The pattern of water withdrawal for agriculture in the US is even more dramatic (Figure 15). Large agricultural water withdrawals from surface water and groundwater are dominantly West of the Mississippi. This is evident from a state-by-state map view and shown even more clearly when plotted simply from West to East (Figure 15, bottom panel).

| State | Water Withdraws million gal/day |

|---|---|

| Hawaii | 100 |

| Alaska | 100 |

| Oregon | 250 |

| Washington | 500 |

| California | 200 |

| Nevada | 100 |

| Idaho | 100 |

| Arizona | 100 |

| Utah | 250 |

| Montana | 100 |

| Wyoming | 100 |

| New Mexico | 100 |

| Colorado | 200 |

| North Dakota | 100 |

| South Dakota | 100 |

| Nebraska | 100 |

| Texas | 2200 |

| Kansas | 100 |

| Oklahoma | 100 |

| Minnesota | 200 |

| Iowa | 300 |

| Missouri | 100 |

| Louisiana | 3200 |

| Arkansas | 250 |

| Wisconsin | 500 |

| Mississippi | 300 |

| Illinois | 400 |

| Alabama | 500 |

| Tennessee | 800 |

| Indiana | 2400 |

| Kentucky | 250 |

| Michigan | 700 |

| Georgia | 600 |

| Ohio | 650 |

| Florida | 250 |

| South Carolina | 300 |

| West Virginia | 1100 |

| North Carolina | 300 |

| Virginia | 500 |

| Pennsylvania | 900 |

| Maryland | 250 |

| D.C. | 100 |

| New York | 300 |

| Delaware | 100 |

| New Jersey | 100 |

| Connecticut | 200 |

| Vermont | 100 |

| Massachusetts | 200 |

| Rhode Island | 100 |

| New Hampshire | 100 |

| Maine | 250 |

| Puerto Rico/US Virgin Islands | 100 |

| State | Water Withdraws million gal/day |

|---|---|

| Hawaii | 200 |

| Alaska | 200 |

| Oregon | 6000 |

| Washington | 3000 |

| California | 24000 |

| Nevada | 1500 |

| Idaho | 16000 |

| Arizona | 5000 |

| Utah | 4000 |

| Montana | 10000 |

| Wyoming | 4000 |

| New Mexico | 2000 |

| Colorado | 13000 |

| North Dakota | 200 |

| South Dakota | 200 |

| Nebraska | 9000 |

| Texas | 8500 |

| Kansas | 2000 |

| Oklahoma | 500 |

| Minnesota | 300 |

| Iowa | 200 |

| Missouri | 1500 |

| Louisiana | 900 |

| Arkansas | 9000 |

| Wisconsin | 300 |

| Mississippi | 2000 |

| Illinois | 500 |

| Alabama | 200 |

| Tennessee | 200 |

| Indiana | 200 |

| Kentucky | 200 |

| Michigan | 300 |

| Georgia | 750 |

| Ohio | 200 |

| Florida | 3500 |

| South Carolina | 200 |

| West Virginia | 200 |

| North Carolina | 200 |

| Virginia | 200 |

| Pennsylvania | 200 |

| Maryland | 200 |

| D.C. | 200 |

| New York | 200 |

| Delaware | 200 |

| New Jersey | 200 |

| Connecticut | 200 |

| Vermont | 200 |

| Massachusetts | 200 |

| Rhode Island | 200 |

| New Hampshire | 200 |

| Maine | 200 |

| Puerto Rico/US Virgin Islands | 200 |

The source of the water we use also provides clues about where water may be most readily available, and/or where typical rainfall and snowmelt cannot meet demand. Inspect the maps below (Figure 16). Surface water withdrawals are spread more or less uniformly across the U.S., and reflect overall water use reasonably closely. This is influenced in large part by total population, energy production, and industrial and agricultural activity (i.e. CA, TX, NY, and FL are the most populous states). However, groundwater withdrawals (obtained by pumping at wells) are a good indication that surface water flows alone are not sufficient to meet demand.

| Amount (million gals./day) | States (random order) |

|---|---|

| 1500-3200 | CA |

| 600-1500 | ID, TX, CO, IL, MI, OH, NY, NC, VA, TN, |

| 300-600 | OR, MO, WI, IN, PA, NJ, DE, SC, AL, LA, AK |

| 300 | All others |

| Amount (million gals./day) | States (random order) |

|---|---|

| 1500-3200 | n/a |

| 600-1500 | CA |

| 300-600 | TX, NE, AK |

| <300 | All others |

Demand for Water

Demand for Water

As shown in the Freshwater Resources section, water demand varies by culture and country, while water availability is dependent on climate and geography (see also Module 2). Some areas of the world are already experiencing freshwater shortages and/or their water supplies are unsanitary as the result of improper treatment of waste and inadequate infrastructure to transport and store potable water. The combined specters of climate change and rapid population growth create uncertainty in planning future water supplies.

Future Demand for Water

Future Demand for Water

What will the future bring?

What will the future bring? Good question, right? How can we gauge what water demand and availability will be in the future, particularly with projected large increases in population and potential climate change superimposed? Not to alarm you, but to inform you, we will go through the exercise of making such projections, both for the U.S. and, on a more limited basis, for the world. What do we need to know for making such estimates? First, let's jot down some ideas. Then we will continue the process below.

Food for Thought

1. What do you think we would need to know in order to predict future demand for water? Take a minute to jot down what you think one would need to take the first crack at this.

ANSWER: Answers will vary. Clearly, we will need to know something about population growth and climate.

First, here is an expert opinion as to how the future will go…

In Human Population and the Environmental Crisis Ben Zuckerman and David Jefferson write: “At a low population density, a society may be able to derive its water from rivers, natural lakes, or from the sustainable use of groundwater. As the population grows, so does the volume of water needed (we will assume demand is proportional to population size). Moreover, levels of waste discharge into the environment will grow as the population rises. Thus, the available unmanaged supplies deteriorate at the same time that demand on them is increasing…A destructive synergy is at work: population size affects the water resource in a manner that is not one of simple proportionality.”

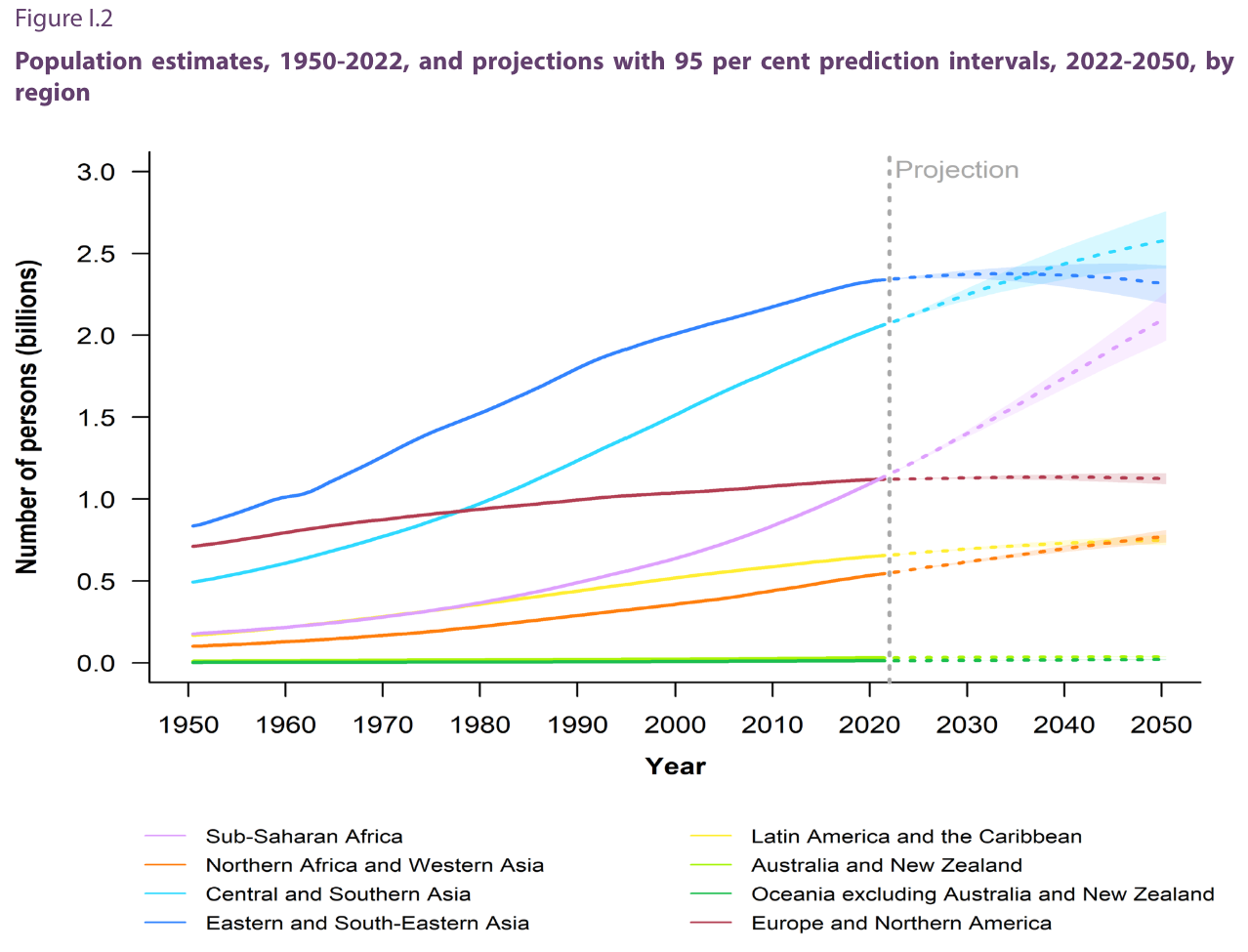

What was it Yogi Berra (N.Y. Yankees catcher and later Manager) infamously said…"It's tough to make predictions, especially about the future." Well, that is a truism, but let's see what projections are being made regarding future population growth, because, clearly, that's one of the inputs we need to determine potential future water use globally.The present global population (as of 2024) is approximately 8.05 billion people. Interestingly, the top three countries, in terms of population, are China, India, and, yes, the United States, in that order (Figure 17). But, by 2050 the global population is estimated to be 9.7 billion people by the United Nations—a staggering 20% increase in the next, say, 26 years! So, at the minimum, if we assume that water use will increase linearly on a per person basis, we would expect that this rate of growth will require 20% more fresh water by 2050. Is that a problem? Do we have excess capacity to supply this water?

Population Growth vs. Water Needs

Population Growth vs. Water Needs

Do we have excess capacity to supply this water? That is an important question, but you have probably already determined that the real issue is where the population growth occurs and what water resources are available there. The major growth is projected to occur in developing countries (Figure 17). African nations are likely regions for greater than average growth. Interestingly, much of Africa is estimated to have significant groundwater resources (BGS, 2013) that could be developed if necessary. In fact, Nigeria is projected to surpass the population of the U.S. by 2050 (Figures 17-19). One must examine the population density and rate of projected growth vs. water needs. In addition, climate change impacts must be considered.

1950- total population 2.5 bn

- China- .5 billion

- India

- United States

- Russia

- Japan

- Indonesia

- Germany

- Brazil

- Britain

- Italy

2013- total population 7.2 bn

- China-4 bn

- India

- United States

- Indonesia

- Brazil

- Pakistan

- Nigeria

- Bangladesh

- Russia

- Japan

2050 forecast- total population 9.6 bn

- India-7 bn

- China

- Nigeria

- United States

- Indonesia

- Pakistan

- Brazil

- Bangladesh

- Ethiopia

- Philippines

Learning Checkpoint

1. What is the relationship between Total Fertility and Per Capita Income shown in Figure 19 above?

ANSWER: Fertility is inversely related to income worldwide. There are several drivers of this relationship, including infant mortality, need for agrarian labor, etc.

2. Why might this be an important consideration when considering future demand for water?

ANSWER: The greatest growth is likely to occur in areas with the least access to infrastructure for accessing, treating, and distributing fresh water.

Increased Impacts of Climate Change on Demand

Increased Impacts of Climate Change on Demand

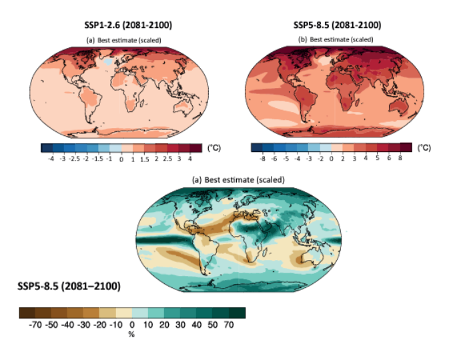

We would probably be better off examining the impacts of climate change on water availability that would increase "water stress," then compare these stresses with those caused by increasing demand, either by population growth in a given region (personal or agricultural demands) or increased water usage resulting from new demands (e.g., energy production) (Figure 20). A number of studies have predicted water supply vs. water demand relationships resulting from climate change. A study by MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) researchers (Schlosser et al., 2014) compared the potential impacts of climate change, on the basis of projected greenhouse gas emission increases in a complex Earth-system model, on water stress in 282 assessment regions (large or multiple watersheds) globally, holding demand constant, to the potential impacts of population growth in the same regions.

| Country | Increase/Decrease | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| US | Increase | 28 |

| Mexico | Increase | 32 |

| Brazil | Increase | 18 |

| Germany | Decrease | 13 |

| Nigeria | Increase | 176 |

| Kenya | Increase | 138 |

| India | Increase | 34 |

| China | Increase | 2 |

| Japan | Decrease | 15 |

| Russia | Decrease | 16 |

They found that, in most regions, projected population growth with increased demand to 2050 was the greater stressor. These researchers use a Water Stress Index (WSI) defined as WSI = TWR/RUN+INF (TWR is total water required for a given watershed region, i.e. all consumptive uses, RUN is available runoff within the watershed, and INF is inflow to the watershed from adjacent regions. The cutoffs used for interpreting water stress are: WSI<0.3 is slightly exploited, 0.3≤WSI<0.6 moderately exploited, 0.6≤WSI<1 heavily exploited, 1≤WSI<2 overly exploited, and WSI≥2 extremely exploited as originally set out by Smakhtin et al. (2005).

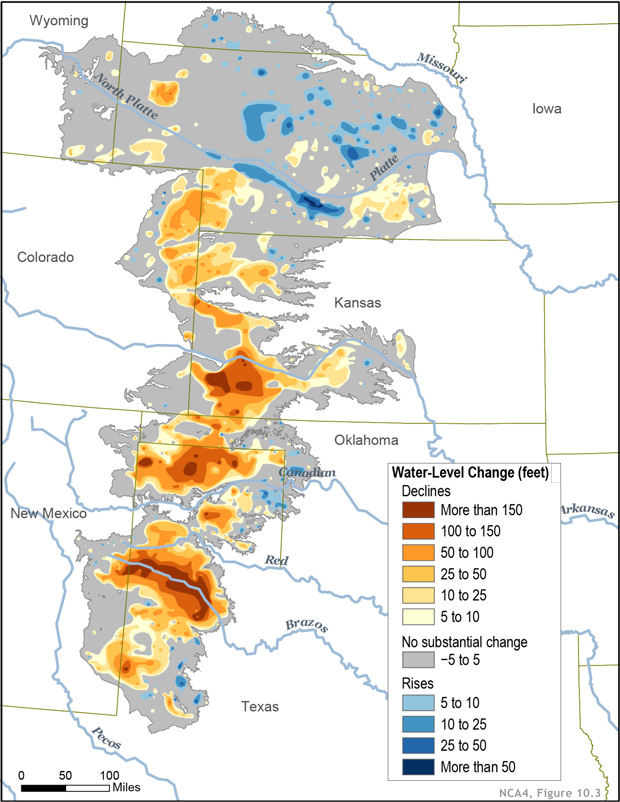

It appears that a substantial proportion of Africa, all of the middle East, India, and central Asia will see increased water stress in the next few decades, largely due to projected population increases. Even the southwestern U.S. is projected to experience expansion and intensification of water stress, but, in this case, mostly as the result of climate change and longer-term drought. Interestingly, the major central U.S. groundwater source, the Ogallala Aquifer, does not appear to be a candidate for significant stress except at its southern end in Texas. However, other studies (see Module 7) suggest that depletion of this aquifer will be more severe.

Possible Solutions for Meeting Water Demand in Stressed Regions

Possible Solutions for Meeting Water Demand in Stressed Regions

There are a number of possible methods to enhance supplies of fresh water, each of which has an economic, political, and/or environmental impact.

Learning Checkpoint

1. Provide three examples of potential ways to increase fresh water supplies.

ANSWER: Answers may vary. There are a number of potential strategies, including 1) Build large dams to increase water storage; 2) Bank water in groundwater storage; 3) Encourage transfers from other consumptive uses and/or conservation; 4) Increase recycling and reuse of wastewater; 5) Desalination of seawater or shallow saline groundwater.

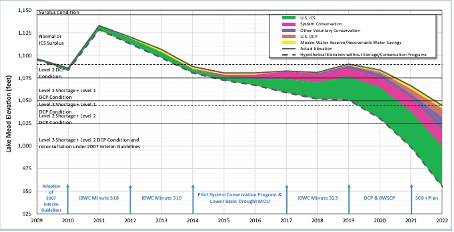

Some of these strategies have been alluded to previously (e.g., encouraging transfers from agricultural use to drinking water supplies). Water storage behind dams is an old strategy and problematic in a number of ways (see Module 6), including high costs, environmental impacts, and political issues that arise when major rivers flow through multiple countries. Nonetheless, there is still major proposed and ongoing dam building in China and other countries.

Groundwater banking is a newer strategy that requires replenishment of aquifers with treated wastewater and/or with runoff available during times of excess. Costs are associated with treating, impounding, and injecting the water (see Module 7). This will mainly benefit regions with significant groundwater resources.

Recycling and reuse are gaining support with successful projects in the U.S. and elsewhere. Penn State University recycles and reinjects nearly 98% of its treated wastewater and has done so since the 1960s. Orange County, CA, has another successful system (see Module 8). Such systems must overcome consumer opposition, however, because of the perception that consumers will be drinking, well, toilet water! Nonetheless, the water quality in such systems is as good or better than that in municipalities that draw water from rivers downstream from other municipalities that discharge treated wastewater into the same river. Another form of reuse is to employ "gray" water (only partially treated) for irrigation of golf courses in arid to semiarid, water-stressed regions. Las Vegas, NV, has implemented such a system, coupled with the removal of water-hungry turf, for which the economics work and conservation is encouraged.

Desalination may be a last resort because of the costs of energy required to remove salts from seawater or water pumped from saline aquifers in non-coastal regions. However, in water-poor but hydrocarbon-rich middle-Eastern countries the economics may support the desalination of seawater. Alternative energy sources (e.g., solar) or emerging processes such as chemical reverse osmosis may be economical in the future as they become more efficient and less costly. And, of course, if water is deemed to have significant value in the future, the high costs may be more acceptable.

Finally, there are still proposals to import or export water from regions replete with fresh water resources (e.g. Alaska) to severely water-stressed regions (e.g. India). However, the costs of transporting such a commodity across the oceans would appear to exceed the value of that water at its terminus.

All of these strategies will be explored in later modules in more detail.

Pricing Water

Pricing Water

Does water have value? If so, how do we set a price for it? And, if we agree that individual access to fresh water is a basic human right or expectation globally (is this generally agreed?), how do we treat water as a commodity? Do we really pay what water is worth?

Pricing Varies

Pricing Varies

You are likely all too familiar with bottled water—that convenient liter-sized plastic bottle containing some sort of water, commonly tap water, or filtered spring water, sometimes treated…it appears that, in the U.S., we pay for the convenience of "grab-and-go." For that convenience, we typically pay about $4/gallon, more than we presently pay for a gallon of gasoline! In most municipalities; however, the cost of water delivered in pipes to taps in homes costs far less ($0.003-0.006/gallon). survey by CircleofBlue.org for 2019 water pricing in 30 cities across the U.S. found an average increase of 3.2% in monthly bills for a family of four using an average of 100 gals/day each (12,000 gals/mo or 45.4 m3/mo) from 2018 to 2019, costing an average of $72.93 a month.

Monthly rates for some representative municipalities are shown in the table below, based on data in the CircleofBlue.org 2014 survey and information from water authority websites for some municipalities not covered in that survey (Pittsburgh, PA and State College, PA).Note the large range in rates that do not seem to make sense geographically. For example, arid Phoenix, AZ has the lowest rate, with Las Vegas, NV not far behind, whereas high precipitation, seemingly water-rich regions such as Seattle, WA and Atlanta, GA top the rate list. Note that Los Angeles, CA, Phoenix, AZ, and Las Vegas, NV all depend on Colorado River water, although Los Angeles also draws on northern California sources and all require significant transport infrastructure. So, in part, this disparity in rates results from the costs of maintaining infrastructure and the numbers of households served, as well as the local abundance of water.

| Municipality (city, state) | Monthly rate (12,000 gals) | Percentage change (2014-2013) |

|---|---|---|

| Phoenix, AZ | $38.75 | 0 |

| Chicago, IL | $39.72 | +14.9 |

| Las Vegas, NV | $42.27 | +2.8 |

| State College, PA | $47.40 | 0 |

| New York, NY | $57.28 | +5.6 |

| Philadelphia, PA | $65.88 | +5.0 |

| Los Angeles, CA | $75.98 | +14.5 |

| Atlanta, GA | $91.92 | 0 |

| Seattle, WA | $98.77 | +9.3 |

| Pittsburgh, PA | $100.81 | ? |

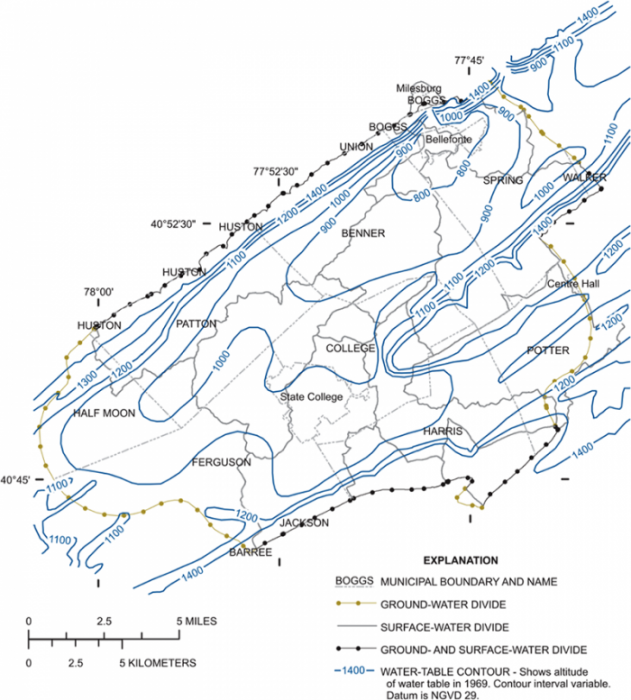

Chicago, IL, for example, has nearby Lake Michigan as a source and a large number of users and its rates are relatively low. Little State College, PA has a significant, sustainable groundwater resource (see Module 6), even though the user base is relatively small. Many municipalities have higher rates because they are financing necessary improvements in infrastructure, which can be quite costly.

Municipalities have adopted different methods for scaling water prices. Some, such as Philadelphia and Detroit, provide cost reductions for larger users (decreasing block), some, including New York, have uniform pricing, whereas others, such as Las Vegas and Atlanta, have implemented tiered pricing (block increases) that encourage conservation while trying to maintain the user base. The objective of all municipalities is to sustain income and provide for future infrastructure requirements.

Internationally, pricing varies even more than in the U.S. Figure 22 illustrates average water prices (Kariuki and Schwartz, 2005) and the impact of non-public water suppliers on the cost to the consumer. Where public utilities are not available, the cost to the consumer can be a factor of 10 higher. In part, this occurs because of increases in cost to the water supplier to purchase water from a public or private supplier because of the large volumes purchased with prevailing block pricing increases. Figure 23 shows the step increases for several African and Indian cities. Recall that the average family of four in the U.S. would use about 45 m3/month, but average usage is probably much lower in many developing nations with lower standards of living. Step increases in block pricing appear to be a fair method of pricing to allow low cost for low-volume users and encouraging conservation by imposing higher costs for larger-volume users.

The Water and Energy Nexus

The Water and Energy Nexus

Considerations of water pricing are complicated because of the multitude of factors that must be taken into account. These include availability and dependability of water supply locally, state of the distribution infrastructure, and the distribution and size of the user base. Dependability is related to climate impacts, such as prolonged droughts that deplete water reserves. A recent study (Watergy Nexus: The Complex Relationship and Looming Crisis Between Our Thirst For Water and Our Hunger for Energy [18]) highlights an additional factor—the amount and cost of energy to acquire, transport, and treat water. This study argues that the cost of energy (usually electricity, but including fuel if the water is trucked in) must be considered in pricing water. The study uses data for 2013, a year of severe drought in much of the western and central U.S. to show how water prices should be adjusted to guarantee supply and cover costs of acquisition. Although the U.S. Geological Survey indicates that the average energy required to provide 1000 gallons (1 kgal) of water is 1.9kWh of electricity, water-stressed regions such as northern California (3.5 kWh/kgal) and highly stressed southern California (11.1 kWh/kgal) require far more (Figure 24). However, the study suggests that municipalities are not taking this factor into consideration in providing a durable and resilient water supply. During times of water stress, municipalities may have trouble meeting costs, and begin to examine other strategies, such as privatization. Of course, when water availability becomes restricted, costs can go up as in California with severe drought conditions (e.g., see the news article In dry California, water fetching record prices [19] about California water pricing: ).

Learning Checkpoint

1. What factors drive water pricing?

ANSWER: Factors that must be considered include: the availability and dependability of water supply locally, state of the distribution infrastructure and potential costs needed to improve or maintain it, cost of delivery – including energy, distribution, and size of the user base, and demand.

Privatization

Privatization

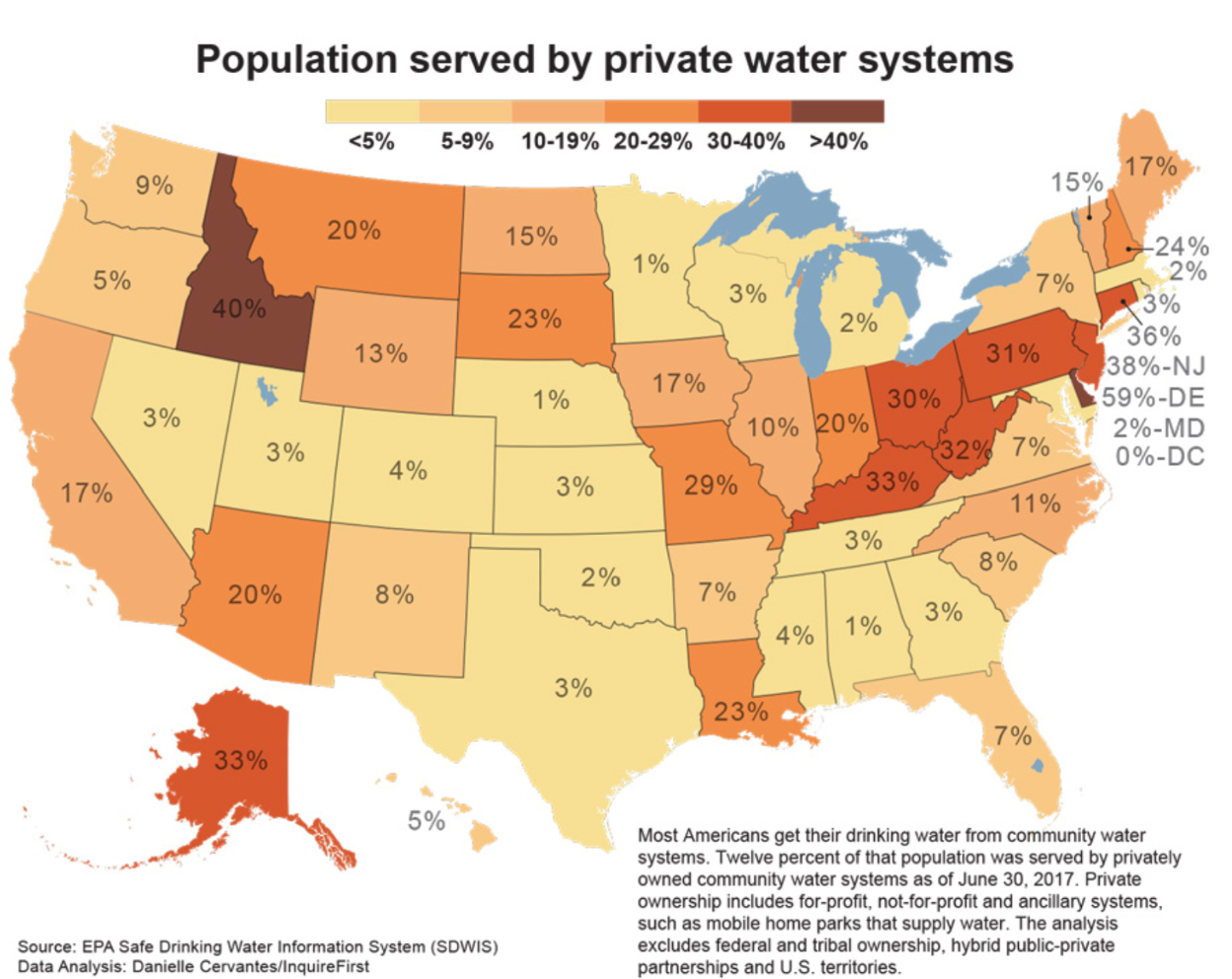

Cash-strapped municipalities with failing water systems might be tempted to contract with private companies to manage their water and sewer systems. Economic drivers, such as the collapse that occurred in 2008, affect users ability to pay for public water systems. In the U.S., about 20% of water supplies are privatized at present. In evaluating this option, one must keep in mind that corporations are for-profit entities, and will need to recoup the full costs of providing water while adding a margin for profit to benefit the corporation and/or their stockholders. Public utilities can be held responsible for controlling costs and providing clean water supplies, whereas it is more difficult for the public to do so for private companies.

There are a number of examples where privatization has apparently failed consumers. Pushed by the costs of renovating their failing water supply infrastructure, Atlanta, GA, for example, handed over control of their water system to United Water, which took over in 1999, with a 20-year contract. Atlanta had long-deferred most maintenance because their revenue was insufficient to cover the full cost of providing service, and because of rapid population growth and their aging system, expansion and improvement were required. Their sewage system was more of a problem than the water supply system, and they were being sued under the U.S. Clean Water Act for that problem as well.

But, in 2003, the city of Atlanta withdrew from the agreement because a number of issues with United Water (see What Can We Learn From Atlanta's Water Privatization [21] for the full story), which included costs, viewed as excessive, and poor performance in maintenance, meter installation, and bill collection.

The situation in Detroit has been much in the news of late (for example – see this MSNBC article, Detroit residents and national allies protest water shutoffs [22]). As a result of the economic downturn, the Detroit Water and Sewer Department has recently gone on a campaign to force users to pay their outstanding water bills with the threat of cutoffs. In addition, the city of Detroit is pursuing the possibility of privatizing its water and sewer systems. Although clearly having its own perspective and position, an interesting argument against water privatization in Detroit [23] is found on The Blue Planet Project website. One common argument against privatization is the rapid increase in the costs of water to consumers. Of course, in many cases, this may occur because the public purveyor was not charging for the full cost of providing the water in the first place.

Michigan lawmakers propose that water bills are capped at 3% of households income and $2 added to bills that can afford to make up for lost income. Claiming that shutting off water is a human rights violation. Read more here. [24]

A 2022 Cornell Chronical story explains that private ownership had the largest impact on annual water bills, which averaged $144 higher in privately owned systems than in public sector systems. Low-income households served by private operators spent 4.4% of their income on water service, about 1.5 percentage points more than in communities with public ownership.

Module 2: Climatology of Water

Module 2: Climatology of Water

Overview

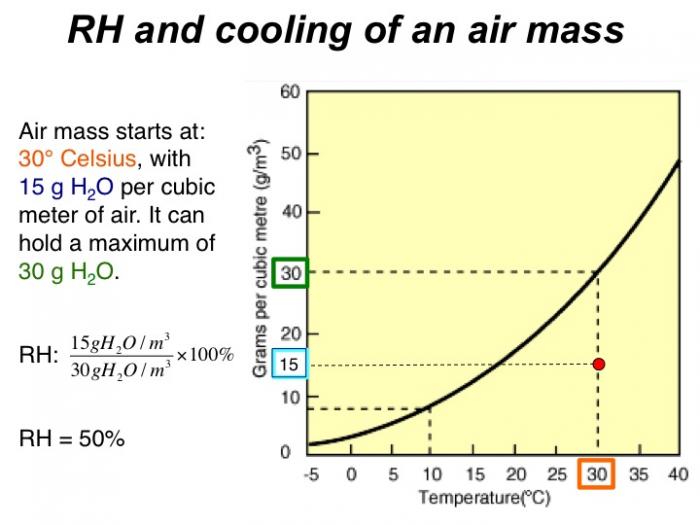

In this module, we will investigate the underlying causes of variations in precipitation on Earth, with a specific focus on large-scale climate belts and the role of mountain ranges in affecting the distribution of rainfall (and snow). The goals of the module are to develop a quantitative understanding of the physical processes that control the distribution of precipitation, and which ultimately govern regions where water is abundant and where it is scarce, both across the U.S. and globally. As part of this, you’ll develop facility with the concepts of relative humidity, saturation, water vapor content in the air, and how these vary with changes in temperature - all of which play a key role in determining when and where precipitation falls.

Goals and Learning Objectives

Goals and Learning Objectives

Goals

- Explain the distribution and dynamics of water at the surface and in the subsurface of the Earth

- Interpret graphical representations of scientific data

Learning Objectives

In completing this module, you will:

- Identify the unique physical properties of water that contribute to its fundamental role in driving Earth Systems

- Identify U.S. and global precipitation patterns by reading precipitation maps

- Quantitatively compare fluxes of water in the hydrologic cycle

- Calculate relative humidity, and use it to quantitatively explain Earth's first-order patterns of precipitation

- Assess the relationship between precipitation, topography, and location on the globe

Unique Properties of Water

Unique Properties of Water

Water has some unusual properties that most of us do not really appreciate or understand. These properties are crucial to life and they originate from the structure of the water molecule itself. This sidebar will provide an overview of water's properties that will be useful in understanding the behavior of water in Earth's environment.

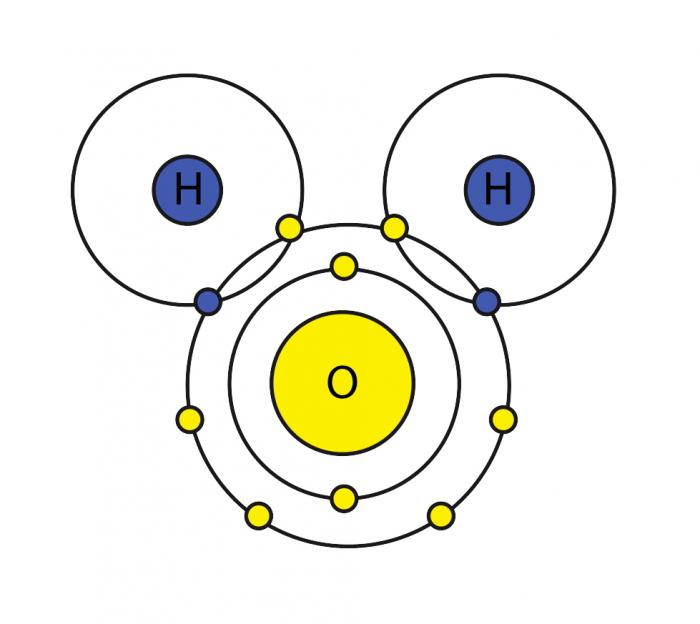

The Configuration of the Water Molecule

The Configuration of the Water Molecule

A molecule of water is composed of two atoms of hydrogen and one atom of oxygen. The one and only electron ring around the nucleus of each hydrogen atom has only one electron. The negative charge of the electron is balanced by the positive charge of one proton in the hydrogen nucleus. The electron ring of hydrogen would actually prefer to possess two electrons to create a stable configuration. Oxygen, on the other hand, has two electron rings with an inner ring having 2 electrons, which is cool because that is a stable configuration. The outer ring, on the other hand, has 6 electrons but it would like to have 2 more because, in the second electron ring, 8 electrons is the stable configuration. To balance the negative charge of 8 (2+6) electrons, the oxygen nucleus has 8 protons. Hydrogen and oxygen would like to have stable electron configurations but do not as individual atoms. They can get out of this predicament if they agree to share electrons (a sort of an energy "treaty"). So, oxygen shares one of its outer electrons with each of two hydrogen atoms, and each of the two hydrogen atoms shares it's one and only electron with oxygen. This is called a covalent bond. Each hydrogen atom thinks it has two electrons, and the oxygen atom thinks that it has 8 outer electrons. Everybody's happy, no?

However, the two hydrogen atoms are both on the same side of the oxygen atom so that the positively charged nuclei of the hydrogen atoms are left exposed, so to speak, leaving that end of the water molecule with a weak positive charge. Meanwhile, on the other side of the molecule, the excess electrons of the oxygen atom, give that end of the molecule a weak negative change. For this reason, a water molecule is called a "dipolar" molecule. Water is an example of a polar solvent (one of the best), capable of dissolving most other compounds because of the water molecule's unequal distribution of charge. In solution, the weak positively charged side of one water molecule will be attracted to the weak negatively charged side of another water molecule and the two molecules will be held together by what is called a weak hydrogen bond. At the temperature range of seawater, the weak hydrogen bonds are constantly being broken and re-formed. This gives water some structure but allows the molecules to slide over each other easily, making it a liquid.

The Structure of Water: Properties

The Structure of Water: Properties

Studies have shown that clustering of water molecules occurs in solutions because of so-called hydrogen bonds (weak interaction), which are about 10% of the covalent water bond strength. This is not inconsiderable and energy is required to break the bonds, or is yielded by the formation of hydrogen bonds. Such bonds are not permanent and there is constant breaking and reforming of bonds, which are estimated to last a few trillionths of a second. Nonetheless, a high proportion of water molecules are bonded at any instant in a solution. But this structure leads to the other important properties of water.

We will consider, for the purposes of this course, only six of these important properties:

- Heat capacity

- Latent heat (of fusion and evaporation)

- Thermal expansion and density

- Surface Tension

- Freezing and Boiling Points

- Solvent properties

As mentioned above, these properties have importance to physical and biological processes on Earth. Effectively, large amounts of water buffer Earth surface environmental changes, meaning that changes in Earth-surface temperature, for example, are relatively minor. Thus, the high heat capacity of water promotes continuity of life on Earth because water cools/ warms slowly relative to land, aiding in heat retention and transport, minimizing extremes in temperature, and helping to maintain uniform body temperatures in organisms. However, there are other effects of water properties as well. Its low viscosity allows rapid flow to equalize pressure differences. Its high surface tension allows wind energy transmission to sea surface promoting downward mixing of oxygen in large water bodies such as the ocean. In addition, this high surface tension helps individual cells in organisms hold their shape and controls drop behavior (have you seen "An Ant's Life"?). Also, the high latent heat of evaporation is very important in heat/water transfer within the atmosphere and is a significant component of transfer of heat from low latitudes, where solar energy influx is more intense to high latitudes that experience solar energy deficits.

Video: Water - Liquid Awesome: Crash Course Biology #2 (11:16)

Take a few minutes to learn why water is the most fascinating and important substance in the universe.

Ah, hello there, here at crash course HQ we like to start out each day with a nice healthy dose of water in all its three forms it is the only substance on all of our planet Earth that occurs naturally in solid liquid and gas forms and to celebrate this magical bond between two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom here today we are going to be celebrating the wonderful life-sustaining properties of water but we're going to do it slightly more clothed. Much better.

We left off here at the biology crash course we're talking about life and the rather important fact that all life as we know it is dependent upon there being water around I'm just an astronomers are always looking out into the universe trying to figure out whether there is life elsewhere because you know that is kind of the most important question that we have right now I was getting really excited when they find water someplace particularly liquid water, and this is one reason why I and so many other people geeked out so hard last December when on Mars a seven-year-old rover Opportunity found a 20 inch long vein of gypsum that was almost certainly deposited by like long-term liquid water on the surface of Mars and this was probably billions of years ago. And so it's going to be hard to tell whether or not the water that was there resulted in some life, but maybe we can figure that out and that would be really exciting. But why do we think that water is necessary for life? Why does water on other planets get us so friggin excited?

So let's start out by investigating some of the amazing properties of water. In order to do that we're gonna have to start out with this the world's most popular molecule or at least the world's most memorized molecule, we all know about it good old h2o. Two hydrogens one oxygen the hydrogen's each sharing an electron with oxygen in what we call a covalent bond. So as you can see you have drawn my water molecule in a particular way and this is actually the way that it appears it is v-shaped because this big ol oxygen atom is a little bit more greedy for electrons. It has a slight negative charge whereas this area here with the hydrogen atoms has a slight positive charge thanks to this polarity all water molecules are attracted to one another so much so that they actually stick together and these are called hydrogen bonds and we talked about the last time essentially what happens is that the positive pole around those hydrogen atoms bonds to the negative pole around the oxygen atoms of a different water molecule and so it's a weak bond but look they're bonding seriously I cannot overstate the importance of this hydrogen bond so when your teacher asks you what's important about water start out with hydrogen bonds and you should put it in all gaps and maybe some sparkles around it one of the cool properties that results from these hydrogen bonds is a high cohesion for water which results in high surface tension cohesion is the attraction between - like things like attraction between one molecule of water and another molecule of water water has the highest cohesion of any nonmetallic liquid and you can see this if you put some water on some wax paper or some Teflon or something where the water beads up like that some some leaves of plants do it really well. It's quite cool since water adheres weakly to the wax paper or to the plant but strongly to itself the water molecules are holding those droplets together in a configuration that creates the least amount of surface area it's this high surface tension that allows some bugs and even I think one lizard and also one Jesus to be able to walk on what a Cui's of force of water does its limits.

Of course, there are other substances that water quite likes to stick to. Take glass for example, this is called adhesion and the water is spreading out here instead of beating up because the adhesive forces between the water and the glass are stronger than the cohesive forces of the individual water molecules in the bead of water adhesion is attraction between two different substances so in this case the water molecules and glass molecules these properties lead to one of my favorite things about water is the fact that it can defy gravity. That really cool thing that just happened is called capillary action and explaining it can be easily done with what we now know about cohesion and adhesion thanks to adhesion the water molecules are attracted to the molecules in the straw but as the water molecules adhere to the straw other molecules are drawn in by cohesion following those fellow water molecules thank you cohesion the surface tension created here causes the water to climb up the straw and it will continue to climb until eventually gravity pulling down on the weight of the water and the straw overpowers the surface tension. The fact that water is a polar molecule also makes it really good at dissolving things.

It's a good solvent, scratch that water isn't a good solvent, it's an amazing solvent! There are more substances that can be dissolved in water than in any other liquid on earth and yes that includes the strongest acid that we have ever created these substances that dissolve in water is sugar or salt being ones that we're familiar with are called hydrophilic and they are hydrophilic because they are polar and their polarity is stronger than the cohesive forces of the wall, so when you get one of these polar substances in water it's strong enough that it breaks all the little cohesive forces. All those little hydrogen bonds and instead of hydrogen bonding to each other the water will hydrogen bond around these polar substances table salt is ionic and right now it's being separated into ions as the poles of our water molecules interact with it but what happens when there is a molecule that cannot break the cohesive forces of water it can't penetrate and come into it basically what happens when that substance can't overcome the strong cohesive forces of water and can't get inside of the water? That's what we get what we call hydrophobic substance or if something that is fearful of water.

These molecules lacked charged poles they are nonpolar and are not dissolving in water because essentially they're being pushed out of the water by water's cohesive forces water we may call it the universal solvent but that does not mean that it dissolves everything there have been a lot of eccentric scientists throughout history but all this talk about water got me thinking about perhaps the most eccentric of the eccentrics a man named Henry Cavendish he communicated with his female servants only via notes and added a staircase to the back of his house to avoid contact with his housekeeper. Some believe he may have suffered from a form of autism but just about everyone will admit that he was a scientific genius. He's best remembered as the first person to recognize hydrogen gas as a distinct substance and to determine the composition of water in the 1700s most people thought that water itself was an element but Cavendish observed that hydrogen which he called inflammable air reacted with oxygen known then by the awesome name defroster gated air to form water. Cavendish didn't totally understand what he'd discovered here in part because he didn't believe in chemical compounds he explained his experiments with hydrogen in terms of a fire like element called phlogiston nevertheless his experiments were groundbreaking like his work and determining the specific gravity basically the comparative density of hydrogen and other gases with reference to common air it's especially impressive when you consider the crude instruments he was working with this for example is what he made his hydrogen gas with he went on not only to establish an accurate composition of the atmosphere but also discovered the density of the earth not bad for a guy who was so painfully shy that the only existing portrait of him was sketched without his knowledge so for all of his decades of experiments only published about 20 papers in the years after his death researchers figured out that Cavendish had actually pre discovered Richter's law Ohm's law Coulomb's law several other laws that's a lot of freakin laws and if he had gotten credit for them all we would have had to deal with like Cavendish's eight flaw and Cavendish's fourth law. So I for one am glad that he didn't actually get credit.

We're gonna do some pretty amazing science right now you guys are not going to believe this okay you ready, it floats. Yeah I know you're not surprised by this but you should be because everything else when it's solid is much more dense than when it's liquid just like gases are much less dense than liquids are but that simple characteristic of water that it's solid form floats is one of the reasons why life on this planet as we know it is possible and why is it that solid water is less dense than liquid water while everything else is the exact opposite of that. Well you can thank your hydrogen bonds once again so at around 32 degrees Fahrenheit or zero degrees Celsius if you're a scientist or from a part of the world where things make sense water molecules start to solidify and the hydrogen bonds in those water molecules form crystalline structures that space molecules apart more evenly in turn making frozen water less dense than its liquid form so in almost every circumstance of floating water ice is a really good thing if I swear denser than water it would freeze and then sink and then freezing than sinking than freezing than sink so just trust me on this one you don't want to live on a world where I sinks not only would it totally wreak havoc on aquatic ecosystems which are basically how life formed on the earth in the first place it would also you know all the ice and the North Pole would sink and then all of the water everywhere else would rise and we wouldn't have any land that would be annoying.

There's one more amazing property of water that I'm forgetting so why is it so hot in here. Oh heat capacity yes water has a very high heat capacity and probably that means nothing to you but basically it means that water is really good at holding on to heat which is why we like to put hot water bottles in our bed and with them when we're lonely but aside from artificially warming your bed it's also very important that it's hard to heat up and cool down the oceans significantly they become giant heat sinks that regulate the temperature and the climate of our planet which is why for example it's so much nicer in Los Angeles where the ocean is constantly keeping the temperatures the same then it is and say Nebraska on a smaller scale we can see waters high heat capacity really easily and visually by putting a pot with no water in it on a stove and seeing how badly that goes but then you put a little bit of water in it and it takes forever to frickin boil oh and if you haven't already noticed this or when water evaporates from your skin it cools you down now that's the principle behind sweating which is an extremely effective though somewhat embarrassing part of life but this is an example of another incredibly cool thing about water when my body gets hot and it sweats that heat excites some of the water molecules on my skin to the point where they break those hydrogen bonds and they evaporate away and when they escape they take that heat energy with them leaving me cooler lovely well this wasn't exercise though I don't know why sweating so much it could be the spray bottle that I keep spraying myself with her maybe it's just because this is such a high-stress enterprise trying to teach you people things I think I need some water but while I'm drinking ah there's review for all of the things that we talked about today if you there are a couple things that you're not quite sure about just go back and watch them it's not going to take a lot of your time and you're going to be smarter. I promise you're going to do so well on that test you either don't or do have coming up okay bye

Heat Capacity

Heat Capacity

Water does not give up or take up heat very easily. Therefore, it is said to have a high heat capacity. In Colorado, it is common to have a difference of 20˚ C between day and night temperatures. At the same time, the temperature of a lake would hardly change at all. This property originates because energy is absorbed by water as molecules are broken apart or is released by molecules of water associating as clusters.

Video: Heat Capacity of Water (01:13)

Take a few minutes to watch the video below to help you understand heat capacity.

The video begins by showing two candles and two balloons. One balloon (the yellow one) is partially filled with water. Both candles are lit and the ballons are moved so they are directly on top of the flame. The balloon without water bursts. This happens because the water absorbs the heat from the flame. The balloon is then picked up to reveal that the bottom of the balloon is burnt.

Latent Heat and Freezing and Boiling Points

Latent Heat and Freezing and Boiling Points

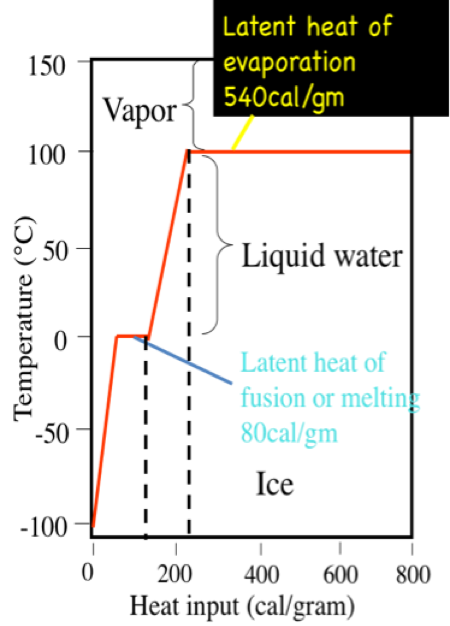

A calorie is the amount of heat it takes to raise the temperature of 1 gram (0.001 liters) of pure water 1 degree C at sea level. It takes 100 calories to heat 1 g. water from 0˚, the freezing point of water, to 100˚ C, the boiling point. However, 540 calories of energy are required to convert that 1 g of water at 100˚ C to 1 g of water vapor at 100˚ C. This is called the latent heat of vaporization. On the other hand, you would have to remove 80 calories from 1 g of pure water at the freezing point, 0˚ C, to convert it to 1 g of ice at 0˚ C. This is called the latent heat of fusion.

Interestingly, the latent heat and freezing and boiling points are controlled by the way water molecules interact with one another. Because molecules acquire more energy as they warm, the association of water molecules as clusters begins to break up as heat is added. In other words, the energy is absorbed by the fluid and molecules begin to dissociate from one another. Considerable energy is required to break up the water molecule clusters, thus there is relatively little temperature change of the fluid for a given amount of heating (this is the heat capacity measure), and, even at the boiling point, it takes far more energy to liberate water molecules as a vapor (parting them from one another). On the other hand, when energy is removed from water during cooling the molecules of water begin to coalesce into clusters and this process adds energy to the mix, thus offsetting the cooling somewhat.

Click here for a text description

Thermal Expansion and Density

Thermal Expansion and Density

When water is a liquid, the water molecules are packed relatively close together but can slide past each other and move around freely (as stated earlier, that makes it a liquid). Pure water has a density of 1.000 g/cm3 at 4˚ C. As the temperature increases or decreases from 4˚ C, the density of water decreases. In fact, if you measure the temperature of the deep water in large, temperate-latitude (e.g., the latitude of PA and NY) lakes that freeze over in the winter (such as the Great Lakes), you will find that the temperature is 4˚ C; that is because fresh water is at its maximum density at that temperature, and as surface waters cool off in the Fall and early Winter, the lakes overturn and fill up with 4˚ C water.