Lessons

Lesson 1: EM SC 240N Lesson 1 Review

Overview

The purpose of this lesson is for you to review key concepts from Lesson 1 (Energy and Sustainability) of EMSC 240N. I strongly encourage you to at least browse through Lesson 1 [1] of EMSC 240N, though that is not required.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- provide a basic description/definition of the following terms/concepts: energy, thermodynamics, the First Law of Thermodynamics, energy efficiency, renewable energy, non-renewable energy, carbon-free, carbon neutral, sustainability, Brundtland Commission, 3 Es, intergenerational equity, and systems thinking;

- identify examples of the above concepts in contemporary culture;

- apply the above concepts in analyses of contemporary issues;

- identify and describe different forms of energy;

- describe how energy can be converted from one form to another; and

- analyze energy-focused charts and graphs.

Lesson Roadmap

| To Read | Lesson 1 Online Content | You're here! |

|---|---|---|

| To Do |

Lesson 1 Quiz Lesson 1 Journal Entry Lesson 1 Discussion Board Post #1 |

Canvas Modules > Lesson 1 Canvas Modules > Lesson 1 Canvas Modules > Lesson 1 |

Questions?

If you have any general course questions, please post them to our HAVE A QUESTION discussion forum located under the Discussions tab in Canvas. I will check that discussion forum regularly to respond as appropriate. While you are there, feel free to post your own responses and comments if you are able to help out a classmate. If you have a question but would like to remain anonymous to the other students, email me through Canvas.

If you have something related to the material that you'd like to share, feel free to post to the Coffee Shop forum, also under the Discussions tab in Canvas.

Energy and Thermodynamics

Thermodynamics is defined by NASA [2] as "the study of the effects of work, heat, and energy on a system." Any time you discuss energy transfer, assess the efficiency of a piece of equipment, or analyze the conversion of energy from one form to another, it involves thermodynamics.

Energy and Forms of Energy

Energy

Energy is defined as "the ability to do work," and work is the transfer of energy or the application of force across a distance. If this were a Physics or Thermodynamics course, we'd be more concerned about work, but for better or worse it is not, so we will stick to focusing on energy. For the purposes of this course, there are a few important things to remember about energy:

- Energy "makes things happen". Energy is required for a computer screen to light up, a car to move, the sun to make plants grow, and your brain to comprehend this sentence. In short, energy is involved in everything that humans can sense (sights, sounds, movement, thoughts, etc.) and many things that humans cannot sense (bacteria digesting waste, atoms holding together, mountains building, etc.). Everything physical around us either has or uses energy.

- Energy cannot be created or destroyed. It can only change forms. This is the First Law of Thermodynamics, sometimes known as the Law of Conservation of Energy. For a summary of the different forms of energy, see below.

- Since energy is the ability to do work, it can be quantified. More energy provides the ability to do more work; less energy provides the ability to do less work.

- Energy can be expressed in a number of different units, and one energy unit can be converted to any other energy unit as long as the unit conversion is known. More on this later in the course.

Forms of Energy

The following discussion of energy forms is taken nearly word-for-word from EM SC 240N. Direct quotes are from this reading from the National Energy Education Development (NEED) Project [3], which you are welcome, but not required, to read.

The two categories of energy are potential and kinetic. Potential energy is stored energy and kinetic energy is energy in motion. The forms of energy are as follows:

Forms of Potential Energy

- Chemical energy is stored in the bonds between atoms and molecules. Common examples include the energy stored in food, fossil fuels, and batteries, but anything that is made of more than one atom has chemical energy. Practically speaking, everything made of matter has chemical energy.

- Mechanical energy is "stored in objects by the application of a force." Common examples include a wound spring, a stretched out rubber band, and compressed air.

- Nuclear energy is "stored in the nucleus of atoms," and is what holds the nucleus together. Anything made of matter has nuclear energy, but most of the nuclear energy converted by humans comes from the fission (splitting) of uranium atoms and is used to generate electricity. Most of the energy used by humans, however, comes from nuclear fusion (fusing of atoms) in the sun.

- Gravitational energy is "energy of position or place." Common examples include water (e.g., in a river) at a high(er) elevation, a ball sitting on top of a hill, and you sitting on your chair right now. If you see naturally flowing water, it is moving downhill (tides and waves notwithstanding), so hydroelectric energy (electrical energy generated from flowing water) starts out as gravitational potential energy.

Forms of Kinetic Energy

- Electrical energy is "the movement of electrons." The most common example of this is electricity moving through a wire, but discharging static electricity and lightning are also electrical energy.

- Radiant energy is also called electromagnetic energy. It travels in transverse waves and is produced by anything with a temperature above absolute zero. Common examples include light, sunlight, microwaves, radio waves, and radiant heat emanating in all directions from a fire.

- Thermal energy is the vibration of the molecules of a substance. As an object or substance gets heated up, the molecules vibrate more rapidly; as it cools, they slow down. Humans cannot see this vibration because it happens at a molecular level, but we can feel it, or at least the results of it. Have you ever accidentally touched a hot stove and gotten burned? That unpleasant sensation is the result of the quickly vibrating molecules of the stove imparting their thermal energy into your skin. Anything above absolute zero has thermal energy, so it is all around us all the time, including everything you see right now.

- Motion energy is the energy in moving objects. Anything with mass that is moving has motion energy. Moving cars, flowing water, a falling object, and even wind (air is made of matter, after all!) are common examples.

- Sound energy moves in waves and is produced by vibrating objects. When you hear something, it is the result of the bones in your ear absorbing and converting these waves into motion energy, which your brain then interprets as sound. Despite what you may have heard, if a tree falls in the woods and there is no one there to hear it, it does generate a sound! Well, it generates sound energy, at least.

Differentiating the various forms of energy is usually straightforward, but I have noticed that people often confuse thermal and radiant energy. This is probably because most people associate "thermal" with "heat," so when something generates heat, it is assumed that thermal energy is being released. Please keep in mind that radiant energy travels in waves, and is released by everything above absolute zero (humans have never observed absolute zero). Radiant energy emanates in all directions from everything, and the hotter the object, the more and more intense radiant energy it emits. All radiant energy is invisible to the human eye except for energy in the visible spectrum. Thermal energy, on the other hand, is energy in the vibrating molecules of a substance. Again, everything above absolute zero has thermal energy, i.e., its molecules are vibrating. Thermal energy is contained within the molecule(s) and is not emitted.

Energy Transfer

Energy is constantly changing forms all around you (and everywhere else on earth) all of the time. All forms of energy can end up as all other forms of energy, and recall that the First Law of Thermodynamics dictates that all energy, irrespective of its form, comes from somewhere else. Again, the following is taken almost word-for-word from EM SC 240N.

Try This

Take a few minutes to look around you. Based on what you know about energy, what is energy “doing” where you are right now? What forms can you identify? (Seriously, take a look.)

Click for answer.

Considering I can't see you right now (Or can I? Hmm...), I'll just give you a few probable examples. If you are inside, light is coming from somewhere, whether it’s a light bulb on the ceiling, sunlight coming through a window, or at least coming from the screen you are looking at (this is electromagnetic/radiant energy). Any sound you hear is sound energy. Everything around you is radiating heat, which is a form of radiant/electromagnetic energy. Since everything in and around you has a temperature above absolute zero, it has vibrating molecules and thus thermal energy. If you are moving at all - even the slightest twitch of an eyelid - your body is using motion energy. Merely thinking about this question requires your brain to use electrical energy.

We could go on and on. But as you probably know, these are all examples of kinetic energy. There are also a number of types of potential energy around you. Think of some examples of potential energy around (and in) you right now. You are able to move and think because of chemical (potential) energy inside of your body. In fact, everything around you has chemical potential energy. Any object on the wall, on a table, attached to the ceiling, or just above the ground has gravitational (potential) energy because it is above the ground. There is also nuclear (potential) energy in all matter because all matter has at least one nucleus. Again, we could go on and on, but the point is that everything around you has potential energy, and thus has the ability to do work, i.e., “to make things happen.”

All of the examples of energy that were noted above came from somewhere else. The light coming from a light bulb is converted from electrical energy running through a wire. The heat radiating from non-living things around you was absorbed from another source such as sunlight or the heating system of the building. The motion and electrical energy your body has right now come from the chemical energy inside of your body. The gravitational energy of things around you came from motion energy required to lift the objects. And so on. And recall that each time energy was transferred, work was done.

Energy Efficiency

Efficiency is an often used term when discussing energy, e.g., "I have an efficient car," "How efficient is your furnace?", and "The average efficiency of a coal-fired power plant is around 33%." Though the term is thrown around a lot, it has a specific meaning. Energy efficiency is the amount of useful output per unit of input. The "useful" part of that definition is important since the First Law of Thermodynamics requires that all energy that goes into something must go somewhere.

- For example, the average internal combustion engine is 28% - 32% efficient, according to the U.S. Department of Energy [5] (U.S. DOE). This means that of all the energy that goes into the engine (chemical energy in the gasoline), only 28% - 32% results in motion energy to move the wheels and electrical energy to operate the various electrical components. Most of the rest is wasted as heat. (Note that only 16% - 25% of the chemical energy ends up actually moving the wheels due to the drivetrain and other losses.)

- Modern natural gas furnaces can be upwards of 97% efficient, which means that 97% of the chemical energy in the natural gas is converted to useful heat that can be delivered to the building, with the remaining 3% lost as waste heat and latent heat in the exhaust. (It is not uncommon for 30% of this energy to be lost in the ducts, according to the U.S. DOE [6], by the way.) Older natural gas furnaces often operate in the 70% - 80% efficiency range.

- According to the U.S. EIA [7], the average coal-fired power plant in the U.S. is about 33% efficient, which means that only about 33% of the chemical energy in the coal ends up as electrical energy. Almost all of the rest is wasted as heat. If you are so inclined, see the video below for a thorough explanation and animation of how a coal-fired power plant works.

Optional Video

The video below provides a very good explanation and animation of how a coal-fired power plant works. Think it's as easy as dumping a bunch of coal into a furnace and turning a turbine? Watch the video to find out.

First Energy operates twenty power plants in the Northeast United States that produce nearly seventy million megawatt-hours of electricity each year for over 4 million residential, commercial, and industrial customers. Over half of First Energy's electricity is produced by using coal, compared to about 60 percent nationwide. Let's see how electricity is generated from coal by taking a virtual tour of a coal-fired power plant similar to those operated by First Energy.

This plant has three generating units that produce more than 2,000 megawatts of electricity. At full capacity, this one power plant can produce enough electricity to supply the needs of one and a half million homes and businesses.

Generating electricity requires a fuel source. At this plant, the fuel source is coal which arrives mainly by a barge but also by rail and truck. Each barge delivers 1500 tons of coal - enough to keep the plant running for a couple of hours. The plant uses about 21,000 tons of coal each day, so over a million tons of coal is stockpiled next to the plant. A device called a stacker reclaimer scoops coal onto a quarter mile long conveyor that can transport up to 900 tons of coal into the plant each hour.

Once inside the plant, up to a thirty-hour supply of coal can be stored in bunkers. Coal moves from the bunkers to feeders to be measured and moved to pulverizers. Each generating unit has 16 coal feeders that supply 8 pulverizers. Coal enters the pulverizer and spins in a large drum where hundreds of steel balls grind it into a fine powder.

Now a fine powder, the coal leaves the pulverizers and heads to the boiler. About 335 tons of coal can be pulverized per hour.

Large fans add warm air to the powdery coal and blow it into the boiler. The boiler has miles of tubes filled with high-quality water. Once inside the boiler, the coal ignites, releasing energy and generating intense heat that changes the water inside the tubes to hot dry steam. The temperature of the steam is now about 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit. This process generates thermal energy which is transformed to mechanical energy at the turbine which is the next stop on our tour.

High-pressure steam, now one thousand degrees Fahrenheit at 3500 pounds per square inch is piped from the boiler to the first in a series of turbines. Here it expands between layers of turbine blades mounted on the turbine shaft. The steam loops back to the furnace, then on to the second turbine. In this process, the steam turns the series of turbines 3600 revolutions per minute providing power to the generator, the last in the series of machines. The generator continuously creates an electrical charge of 34,481 amps at 18000 volts of electricity. From here, the electricity leaves the plant and begins its journey to customers.

After the steam has been used to create electricity, it is exhausted from the turbine and sent to a condenser to be changed back into water. Inside the condenser, steam passes over the outside of pipes filled with chilled water from the cooling towers. The steam condenses to water and returns to the boilers to repeat the steam generating process over again. As the steam condenses, the chilled water inside the condenser pipes becomes warm from the heat of the steam so it is sent to a cooling tower. These particular towers are called natural draft cooling towers, which are designed with no moving parts. Inside, the water splashes over a series of baffles which breaks up the water into small droplets. These droplets mix with air from the open bottom of the tower evaporating some of the water and cooling the rest by as much as 27 degrees. The newly chilled water returns to the condenser to repeat the process of cooling more steam.

Since 1971, First Energy has spent more than $5 billion dollars on environmental protection. Our plants are equipped with air quality control systems to remove sulfur dioxide and particulates called fly ash. Fly ash is removed by a mechanical process and sulfur dioxide is removed with a chemical reaction using lime. These processes take place in large ductwork scrubber trains located between a unit's boiler and its chimney. Boiler gasses pass through scrubbing vessels and are sprayed with slurry, a mixture of water and lime. The sulfur dioxide particles and other pollutants are absorbed by the slurry and fall to the bottom of the vessels. A fan releases the cleansed gases through the chimney. By the time this happens, more than 99 percent of particulates have been removed, as well as ninety-two percent of sulfur dioxide. A plant similar to this one can remove over 400,000 tons of sulfur dioxide each year.

The scrubbing process creates a huge amount of a byproduct called calcium sulfite. This plant could create more than 3 million gallons of calcium sulfite slurry each day. First Energy created a process that turns that waste product into a valuable building material called gypsum which is used to make wallboard or drywall. The slurry leaving the scrubbers is thickened and pumped through a forced oxidation gypsum or fog system. Oxygen is then added changing it into gypsum which is dried, treated, and sent to a gypsum manufacturer to make wallboard.

First Energy recycles about a half million tons of gypsum each year - enough to manufacture wallboard for seventy thousand new homes.

Precipitators are another method of extracting coal ash, also called fly ash, which can be recycled or deposited in landfills. This mechanical process extracts fly ash left over from the combustion process. These poles called rappers shake fly ash from a vibrating wire. Gas from the furnace containing fly ash flows into the box. The fly ash drops into a storage chamber and is blown into silos to be loaded into a truck.

Fly ash from First Energy plants is used in manufacturing a variety of products, including concrete, grouting, roofing shingles, granules, and anti-skid road materials.

First Energy also uses a selective catalytic reduction technology or SCR to reduce nitrogen oxide emissions. SCR systems work much like a catalytic converter on a car. Flue gas containing nitrogen oxide emissions from the combustion process is mixed with ammonia. The mixed gases travel through a series of catalytic layers which causes the nitrogen oxides to react with the ammonia. The reaction converts the nitrogen oxides to water vapor and pure nitrogen, a benign chemical that makes up eighty percent of the air we breathe. Both elements are returned to the environment through the station stacks.

Now that we've taken a look at how electricity is produced and some of the environmental control protection systems used in our plants, let's take a look at how the electricity is delivered to our homes and businesses. Transformers located just outside the plant boost the power from 18,000 volts to 345,000 volts so it can travel long distances over transmission lines to where it is needed. Substations located along the path reduce the voltage so it can be moved along distribution lines attached to the utility poles. As the electricity nears customer locations, transformers on poles step down the power for use in homes and businesses.

(Music) We hope you enjoyed seeing how energy is produced at First Energy, where our energy is working for you.

All energy-using (and generating) technologies have an efficiency - TVs, light bulbs, solar panels, cell phones, wind turbines, airplane engines, electric motors, you name it. One important aspect to know is that when energy is converted, it is physically impossible to convert all of the energy into useful output. In other words, it is not possible for anything to be 100% efficient. This is dictated by the Second Law of Thermodynamics. The Second Law has other implications, but they are not important in the context of this course. If you'd like to learn more about the Second Law, see the video below and/or this [8]link.

Optional - Explanation of the Second Law of Thermodynamics

The second law can be confusing, but the narrator in the video below does a pretty good job of explaining some aspects of it.

Let's talk about the Second Law of Thermodynamics. This law is weird. There are about 10 different ways to state it, which is one reason why it's weird. Let's start with one of the most common ways to state it, which is, if you've got a cold object and a hot object, heat will never be seen to flow spontaneously from a colder object to a hotter object. So if you have these two sitting together, maybe an ice cube and a hot piece of metal, and you make them touch, heat's going to flow between them, but we know what's gonna happen. The heat's gonna flow from the hot object to the cold object, and never the other way. At least, not spontaneously. You can force heat from a cold object to a hot object as we do with a refrigerator or a freezer, but that's using a heat pump. And those refrigerators and freezers are doing work to force that heat from the cold region into the hot region. It won't do it spontaneously by itself. You've got to force it to do it. So what the second law says, or at least one version of it is that that process will never be seen to happen in reverse. The heat will never be seen to flow from the cold object to the hot object. Now, you might be thinking, "Duh. "Do we really need a law to tell us that?" But it's not so obvious, because you can still conserve energy and momentum and all the other rules of physics and laws of physics by allowing heat to flow from the cold object to the hot object. In other words, let's say the cold object started with 10 Joules of thermal energy and the hot object started with ... It's hotter, so let's just say it has 30 Joules of thermal energy. You could imagine five Joules of energy going from the cold object into the hot object which would leave you with five Joules of energy for the cold object, 35 Joules of thermal energy for the hot object. You still have 40, just like you did before. You didn't break the law of conservation of energy. It's just, energy won't go that way. So why? Why is thermal energy never seen to flow from the cold object to the hot object, even though it satisfies every other known law of physics besides the second law? Well, before we answer that question, I think it'd be useful to talk about an alternate version of the second law, which looks something like this. The total disorder will never be seen to decrease. What do I mean by "disorder"? Imagine you had a room and there were blue spheres. And they're bouncing around wildly. So these all have some velocity and random directions. And when they strike a wall or each other, they lose no energy. So they keep bouncing around like crazy. And then there's another section of the room with red spheres, and these are also bouncing around randomly. They lose no energy. They keep doing their thing. Except, there's a divider in this room that doesn't allow the red spheres to go onto the blue spheres' side and vice versa. These can't mix up. So right now, this is an ordered state because the reds are separated from the blues. So we say that this state has a certain amount of order to it. But let's imagine we removed the divider. Now, what's gonna happen? Well, you'll see these things mix up. This blue sphere will move over here, and it'll bounce onto this side. This red sphere will go over here. They'll just keep getting mixed up. And at some given moment, you might find the spheres in some configuration like this. They're still bouncing around, but now they're all mixed up and we say that this state has a higher amount of disorder. This is not ordered. We say that this is more disordered, which supports the second law. The second law says, if you let things do what they wanna do spontaneously, your system will go from a more ordered state to a more disordered state. And you'll never see it go the other way. We can stand in this room and wait. But you're probably never gonna see the blue spheres line up all on the left side and the right spheres line up on the right side. With 12 total spheres, maybe if you wait long enough, a really long time, you might catch it where all the red spheres are on one side and blues are on the other. But imagine this. Imagine now, instead of six reds and six blues, there's 100 reds, 1,000 reds, maybe 10 to the 23d and Avogadro's number of reds, and now they're all mixed up. The odds of ever seeing them get back to this ordered state are basically zero. The probability isn't exactly zero, but the probability is very, very low that you would ever see a disordered state with that many numbers of particles reassemble themselves into an ordered state.

So we kind of just know that from experience and what we've seen in our day-to-day lives. But you still might be wondering, "How come? "How come we never see a disordered state go to an ordered state?" Well, it basically has to do with counting. If you were to count all the possible ways of lining up the reds over here on this side and the blues on the left-hand side, there'd be a lot of combinations that would satisfy that condition. I mean, you could swap this red with that red, and this red with that red, all on the right-hand side. All these reds could get swapped around. And these blues, as well. They can get swapped around on the left-hand side. You get a large number of variations that would satisfy the condition of blues on the left, reds on the right. But now I want you to ask yourself, how many possibilities are there for having blues and reds spread out through the whole room? Well, you could probably convince yourself, there's more. And it turns out, there'll be a lot more. Now this red doesn't just have to maintain its position on the right-hand side somewhere. This red can get swapped out anywhere over here. I can swap a red with this blue, and this blue with this red, and this red with this red, and this blue with this blue. I can move them all over. Now that these spheres have the whole room through which they can mix, the number of states that will have blues and reds mixed throughout the whole room will vastly outnumber the number of states that have just reds on one side and just blues on the other side. And this simple idea is the basis for the Second Law of Thermodynamics. Roughly speaking, the Second Law of Thermodynamics holds because there are so many more disordered states than there are ordered states. Now, I'm gonna tell you something that you might not like. This particular disordered state that I have drawn, this exact one, is just as likely as this exact ordered state. In other words, if I get rid of the barrier over here, if you came in, you'd be just as likely to find the room in this exact configuration as you were to find it in this exact configuration. These two exact states are equally likely, which sounds weird. It makes you think, "Well, you're just as likely to find an ordered state as a disordered state." But no. This particular state is just as likely as this other particular state. But there are so many more mixed-up states than there are separated states. Even though any particular state is just as likely, since the mixed-up states vastly outnumber the separated states, if you pick one at random, it's gonna be a mixed-up state because there are so many more of them. Imagine putting these all into a hat. Imagine writing down all the possible configurations of states, ordered, disordered, in between. You put them all into a hat, you pull one out randomly, any particular state is just as likely. But since there are so many more disordered states, you pick one out randomly, it's probably gonna be mixed up. And if there's a large number of particles, you're almost certain to find it mixed up. So to help us keep these ideas straight, we need some different terms. Physicists came up with a couple terms. One is a macrostate. And a macrostate is basically saying, okay, the particles are mixed up. That's one possible macrostate. And we could be more precise. We can say, the reds and the blues can be anywhere within the box. Another possible macrostate would be to say that the particles are separated, that is to say, reds are on this side, anywhere on that side, but on the right side, and blues are on the left side, anywhere on the left side. These terms are referring to a macrostate, an overall description of what you would see. Now, there's another term, a microstate. And a microstate is a precise, exact description of the nitty-gritty details of what every particle is doing within there. If I just tell you, "The particles are mixed up," you're not gonna know exactly where they are. Similarly, if I just tell you, "They're separated," you're not gonna know exactly where they are. You'll know they'll be on the right-hand side, the red ones will, but you won't know. Maybe this red ones moves down here, maybe this red one moves up here. The microstate is an exact description. This red one's right here, going a particular speed. This blue one's right here, going a particular speed. If you specify the exact location, blue right here, blue right there, going that fast, red right here, what you're describing to me is a microstate. And so the second law, another way of thinking about it, there are more microstates for a disordered macrostate than there are microstates for an ordered macrostate. And that's why we see systems go from order to disorder. It's really just a statistical result of counting up the possible number of states. You might be wondering, what does this have to do with heat going from hot to cold, all this talk about microstates and macrostates? Well, it's not just position that can get disordered. It's velocities that can get disordered, energy that can get disordered, and that's more of like what's happening up here. The positions of the hot molecules aren't necessarily moving over into the cold range. But the energy over here is getting dissipated into the cold area. So image it this way. Let's get rid of all this. And imagine you had a room with gas in it, but this gas was kind of weird. At this particular moment, all the gas molecules on the right-hand side were moving really fast, and all the gas molecules on the left-hand side were moving really slow. So the room was separated into a cold region and a hot region, just like this energy is. This is ordered, or at least, somewhat ordered. It's more ordered than it's going to be. If you wait a while, this is all gonna mix up. You're gonna have some fast-moving particles over here, some slow ones over here. It's all gonna be blended together.

And so, what would you say if you were standing in here? At first, you'd feel cold because these particles don't have a lot of energy. Then you start feeling warmer and warmer. You'd say heat is flowing over to the left because you feel faster-moving particles striking your body. And so you'd rightly say that heat is moving from the right of this room to the left of this room. It flows from the hot to the cold. And that's what's happening up here. Heat flows from the hot to the cold. You might object. These are solids, I said, copper and an ice cube. A copper atom's not gonna make it over into the cold ice cube. But the energy is gonna move. So you can make the same argument over here. Don't allow these, let's say these are the copper atoms moving around fast, or at least jiggling in place rapidly. When they bump into the slower-moving water molecules in the ice cube, they're gonna give those water molecules some of their energy. And this energy's gonna become mixed up. The energy will become disordered. It will go from this ordered state, where the high energy is over here and low energy's here, to a disordered state where the energy's distributed somewhat evenly. So essentially what I'm saying is, if you consider the macrostate, where the hot molecules are separated from the cold molecules, there will be less microstates that satisfy that condition than there will be microstates that satisfy the condition for a macrostate where the energy is mixed up and you're just as likely to find a fast-moving particle on the left as you are on the right. This will have vastly more microstates, many more possible ways of making up a mixed-up state than there are microstates that create a separated state. I mean, there's gonna be a lot. I'm talking a lot of microstates that satisfy this condition for this macrostate, separated. But there will be so many more microstates for the mixed-up case, this dominates. That's why you always see heat flow from a hot object to a cold object, just because it's statistically inevitable with the large number of particles that you have here. There are so many more ways of heat flowing from hot to cold than there are from cold to hot, statistically speaking, you just never see it go the other way. Energy will always, at least spontaneously, if you let it do what it wants to, energy's always going to dissipate and evenly distribute. That's why it goes from the hot to the cold. This energy's trying to get mixed up, just because statistically, there are so many more ways for that to happen. Now, I need to tell you that there's actually a scientific term for the amount of disorder, and we call it the entropy. Physicists use the letter S to denote the entropy. And if you wanna know the formula for the entropy, you could look on Boltzmann's grave. This is Ludwig Boltzmann. He's got it on his gravestone. How awesome is that? The entropy S is k, Boltzmann's constant, times log. This is actually the natural log of W. And W is the number of microstates for a particular macrostate. So you got some configuration, you wanna know the entropy? Just look at what macrostate it's in, count up how many microstates are there for that macrostate, take the log of it, multiply by Boltzmann's constant, that gives you the entropy. And there's a term for this W. It's called the Multiplicity because it's determining the multitude of microstates that satisfy the conditions for a particular macrostate. Now, entropy is cool. Entropy is weird. Entropy is somewhat mysterious and still, probably, has secrets for us to unlock here. I don't have time to go into all of them here, but if you read up on it, entropy has a role to play in the fate of the universe, the beginning of the universe, the arrow of time, maybe our perception, all kinds of facets of physics that are extremely interesting. And entropy, you always find this guy lurking around. And one place you always find entropy is in the Second Law of Thermodynamics because it allows us a third way to state the second law, which is that the total entropy of a closed system will always be seen to increase. Technically, if it's a reversible process, the entropy could stay the same. But honestly, for all real-world processes, the entropy's gonna increase for a closed system, which is to say that the disorder increases.

Renewable and Non-Renewable Energy

Renewable energy is defined by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency [9] thus: "Renewable energy includes resources that rely on fuel sources that restore themselves over short periods of time and do not diminish." Non-renewable energy is energy that cannot restore itself over a short period of time and does diminish. It is usually easy to distinguish between renewable and non-renewable, but there are some exceptions (more on that in a minute).

Non-Renewable Energy

Fossil Fuels

Fossil fuels are fossilized hydrocarbons made from organic material. They are considered "fossilized" because they take millions of years to form, they are hydrocarbons because they are made mostly of hydrogen and carbon, and of course organic material refers to living or recently living things.

The three primary fossil fuels used in the world are coal, oil, and natural gas. (As noted in EM SC 240N, oil and natural gas are technically made up of multiple hydrocarbons, but they are each conventionally referred to as individual hydrocarbons.) Feel free to read through the U.S. Energy Information Administration's (U.S. EIA's) summaries of coal [10], oil [11], and natural gas [12] before reading the summaries below.

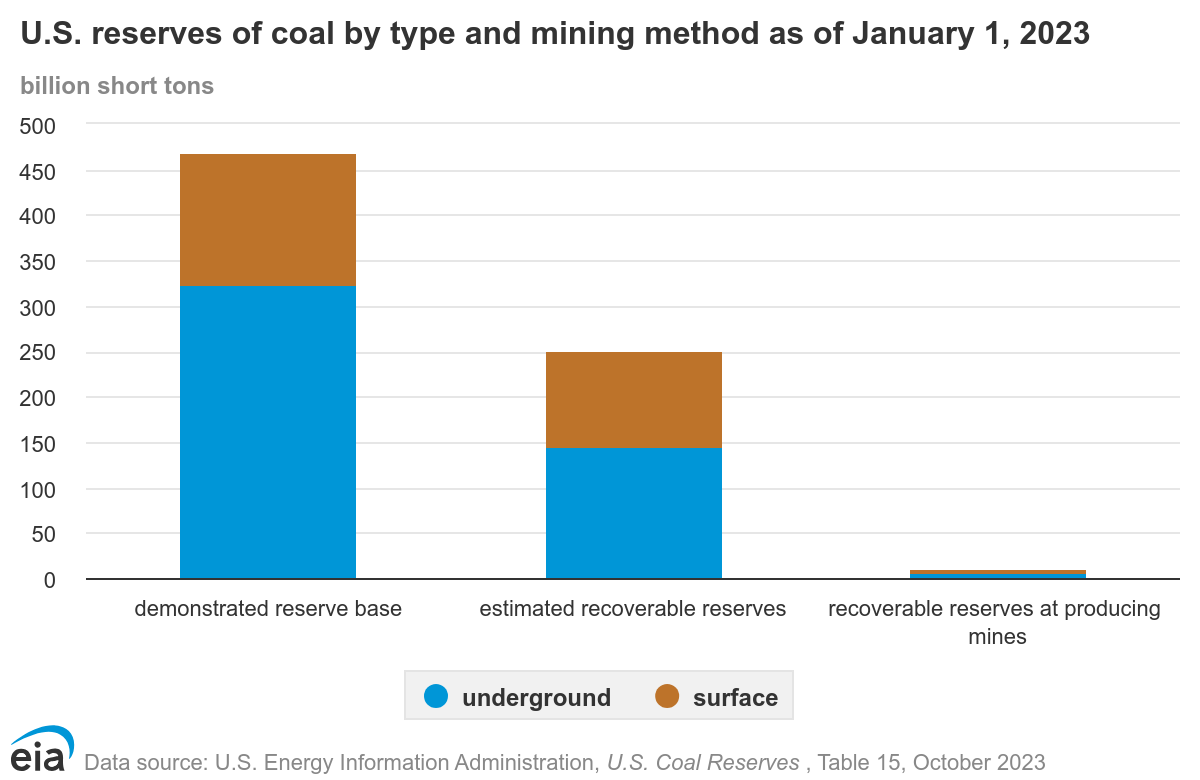

- Coal is formed when organic material (almost entirely plants) dies and sinks to the bottom of swampy areas, and is subsequently buried under sediment for millions of years. There are four main types of coal, listed from lowest to highest heat content (i.e., lowest to highest chemical potential energy per ton): lignite, sub-bituminous, bituminous, and anthracite. Anthracite coal is the shiny black rock that most people probably think of when they think of coal, and the rest are shades of dull black or brown. Anthracite has very high carbon content (86% - 97%, according to the U.S. EIA [10]), and lignite has the lowest at around 25% - 35% carbon. Anthracite is mainly used in the metals industry, and the rest are primarily used to generate energy.

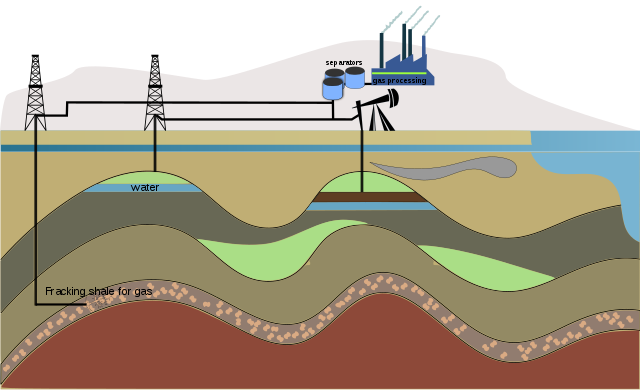

- Oil (aka petroleum, which means "rock oil") is formed when dead organic material (mostly microscopic photosynthetic organisms) die and sink to the bottom of shallow seas, are buried under sediment (usually sand and/or silt), and changed by heat and pressure over millions of years. Most of the oil extracted in the world is found in the pores of rock layers - sandstone (formed from sand grains) and increasingly from shale (formed from silt grains). Shale oil is extracted through hydraulic fracturing ("fracking"), which will be discussed in a future lesson.

- Natural gas is formed by the same process as oil. Natural gas naturally exists as a gas, and like oil is found inside the pores of rocks. Oil and natural gas are almost always found together.

Since all fossil fuels started out as plants or animals, all of their energy comes from the sun. The solar energy (all radiant energy) is stored as chemical energy when the plant undergoes photosynthesis, then is stored as chemical energy in the fossil fuel itself. It is (usually) released when the fuel undergoes combustion, which results in thermal and ultimately radiant energy release. Note that the physical material of fossil fuels does not come from the sun - the carbon, for example, is pulled from the atmosphere during photosynthesis - but the energy that is released when coal, oil, or natural gas is burned was once solar energy.

Nuclear

Nuclear energy, as discussed above, is the energy that holds the nucleus of atoms together. Nuclear energy in nuclear power plants is extracted using fission of uranium atoms. Fission releases radiant energy, which is used to heat water to steam and turn a turbine, which spins a generator and generates an electrical current. The sun utilizes fusion (fusing hydrogen together to form helium atoms), which then releases radiant energy.

Renewable Energy

As noted above, renewable energy sources "restore themselves over short periods of time and do not diminish." For a thorough explanation of many renewable energy sources, see this site from the U.S. EIA [13]. A more thorough explanation of these sources is provided later in this course.

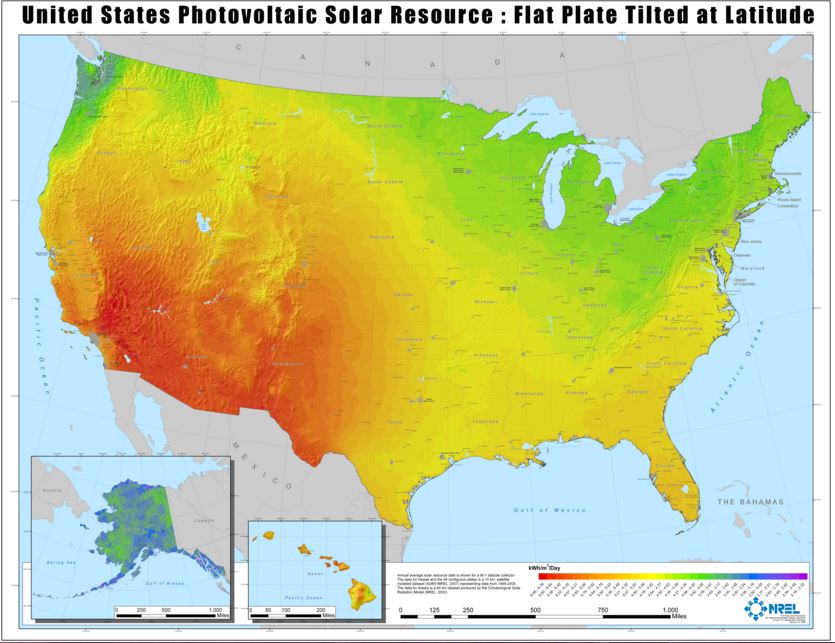

- Solar [14]energy comes directly from the sun. (Recall that it results from nuclear fission, and arrives at the earth as radiant/electromagnetic energy.) Solar photovoltaics (PV) convert solar energy directly to electricity. Solar thermal technologies absorb solar energy and convert it to thermal energy in water or other fluids. Passive solar energy is a form of solar thermal and is when a home or other building uses the sun's energy to heat the inside of the building. Solar energy is constantly replenished, and so is renewable. It is intermittent, of course, which is its main limitation, along with being limited in power output. There is only so much energy per area available at a given time.

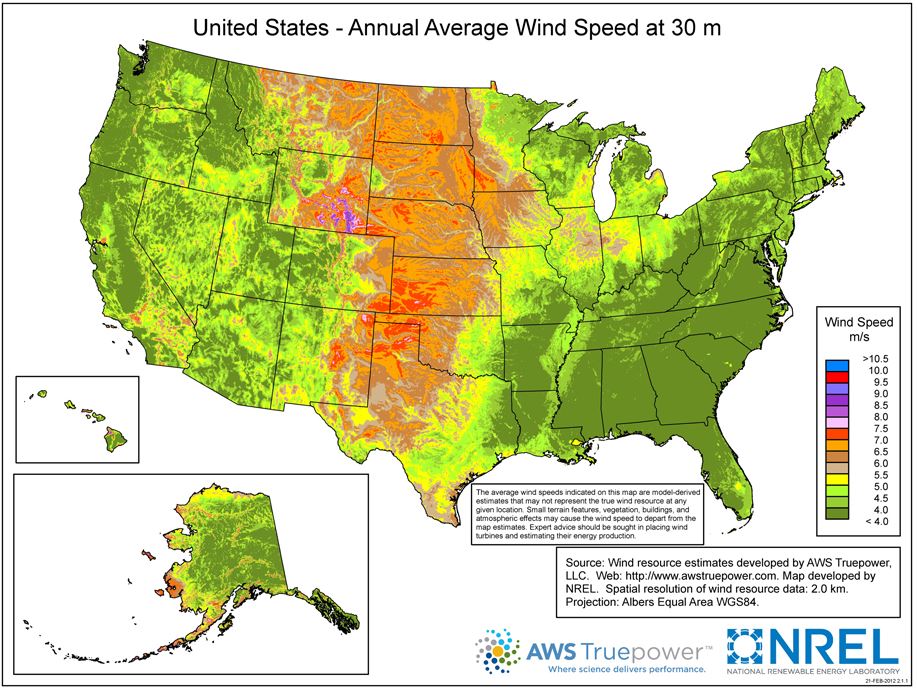

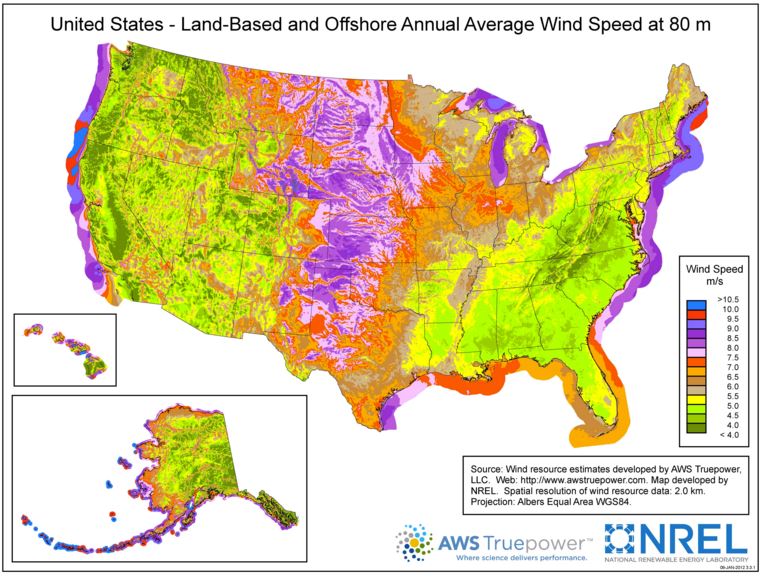

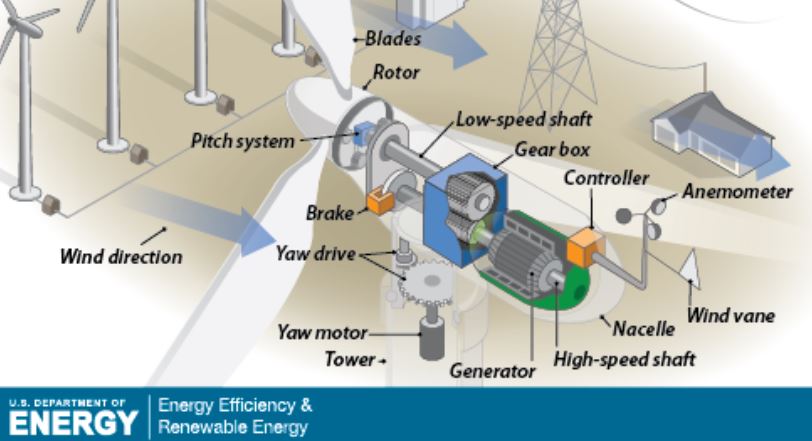

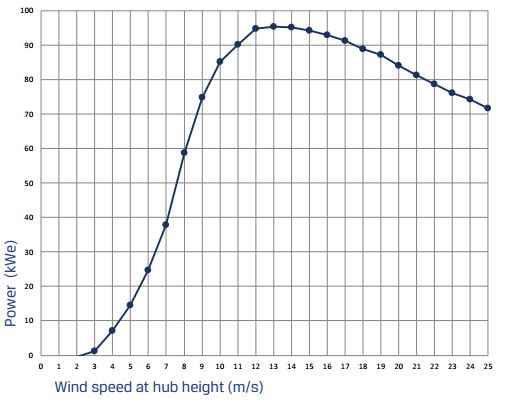

- Wind [15]energy is the motion energy in moving air. Air has mass, and when moving has velocity and thus kinetic energy. The wind energy used by humans is mostly harvested using wind turbines, which utilize wind energy to spin blades, which spins a generator that generates electricity. Air moves from areas of higher pressure to areas of lower pressure. This pressure difference is caused by differential heating (and cooling), which is the result of solar energy as it is absorbed and released by the irregularly shaped earth and different materials the earth is made of. Thermodynamically speaking, kinetic energy in the wind starts out solar energy, and so is renewable. Like solar, the wind is intermittent and limited in amount, but does not "run out."

- Hydropower [16]is energy in moving water (again, mass that has a velocity has kinetic energy). Most of the hydropower used by humans is used to generate hydroelectricity, which is when moving water spins a turbine, which spins a generator that generates electricity. Hydropower also comes from the sun: Water gets its kinetic energy from gravitational energy that causes it to flow downhill. This gravitational energy is the result of water being elevated. The only way water naturally goes uphill is through evaporation, which is almost entirely the result of direct solar energy or wind energy, and evapotranspiration by plants, which is also the result of solar energy. Any way you slice it, hydropower starts as solar energy. Hydropower is limited in scale and location (many places do not have flowing water), but where it does flow, it will often continue to do so, and is thus renewable.

- Biomass [17]is energy from living or recently living things. There are many ways that humans use biomass: burning wood, collecting biogas from sewage and animal waste, converting corn or switchgrass to ethanol, converting vegetable oil or algae to biodiesel, and burning food or agricultural waste are all ways to utilize biomass to generate useful energy. All living things get their energy from the sun - plants directly so, and animals ultimately get their energy from plants. Biomass is thus renewable but is limited in scale and supply. Plants only grow so fast, so if you harvest biomass faster than it is replenished, it is not being used at a renewable rate.

- There are other minor renewable energy sources such as geothermal (thermal energy from the earth), tidal energy (kinetic energy in tides, which results from gravitational energy from the sun and the moon), and wave energy (the result of wind energy that moves over bodies of water).

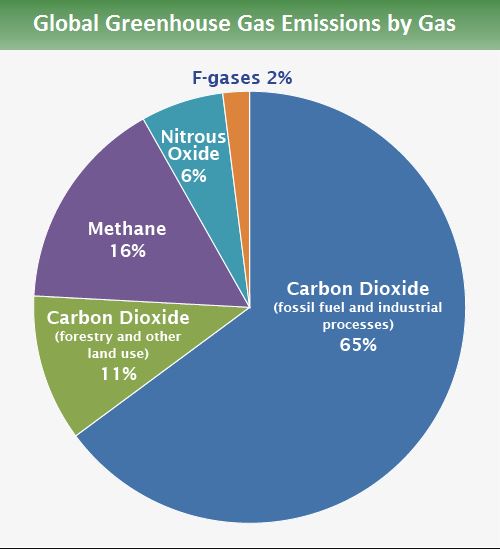

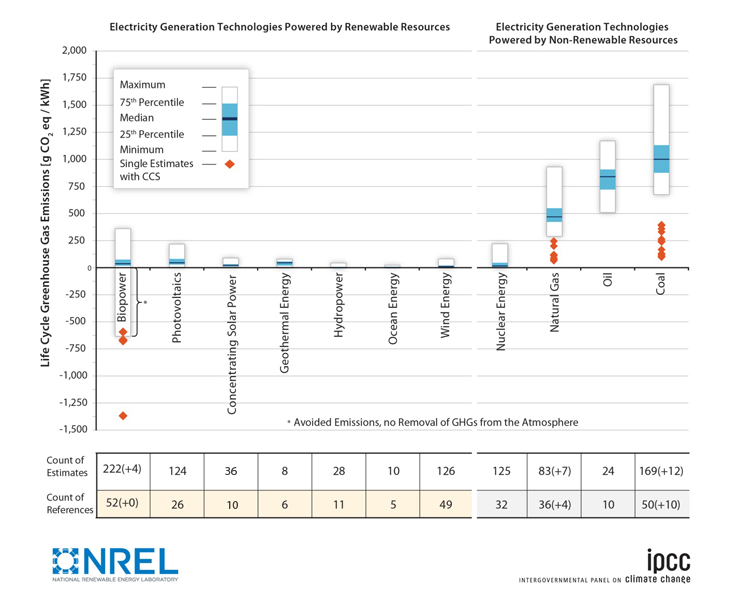

Carbon Free and Carbon Neutral Energy Sources

As you are no doubt aware, a primary sustainability concern regarding energy use is carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. A carbon-free energy source emits no carbon when energy is being generated. Solar, wind, hydroelectric, and nuclear energy are commonly used carbon-free sources. Carbon neutral sources release CO2 but have no net impact on the CO2 concentration of the atmosphere because they release no more CO2 than was absorbed from the same atmosphere. Biomass is the only carbon-neutral source of energy. Recall that biomass gets its energy from the sun by virtue of it being used by photosynthetic organisms to grow. Biomass is made mostly of carbon, which is integrated into the biomass when CO2 is absorbed from the surrounding air. When said biomass is converted to useful thermal/radiant energy via combustion, the same or less CO2 is released, resulting in a net zero impact on carbon dioxide concentrations. To summarize:

- Carbon-free energy sources: solar, wind, hydropower, wave, geothermal, tidal, nuclear

- Carbon-neutral energy source: biomass

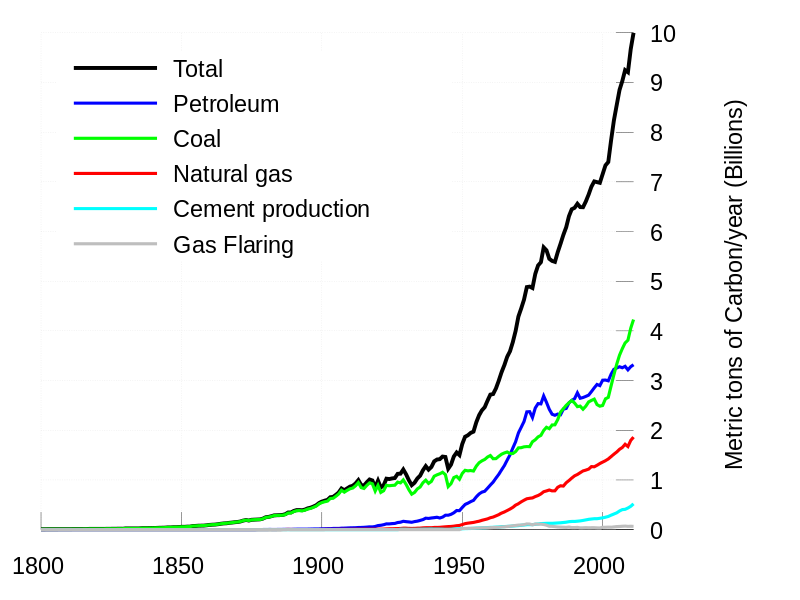

- Carbon-emitting energy sources: coal, oil, natural gas

Sustainability

It will help to at least skim through this page of EM SC 240N [18] prior to reading this material, but it is not necessary.

Key Sustainability Concepts

As I'm sure you are aware, the terms sustainable and green are used in many contexts and in many sectors of society. Sustainable growth, sustainable energy, green business, sustainable fashion, green cars, sustainable food, and sustainable consumption are just a small sample of how the terms are used. Many people in the sustainability field (myself included) are concerned that the term has been overused to the point that it is almost meaningless. Robert Engelman, President of the Worldwatch Institute [19], refers to this phenomenon as "sustainababble" in his "Beyond Sustainababble [20]" chapter from Is Sustainability Still Possible?. While this excessive usage of the term is undesirable, it is in some ways understandable because a) sustainability relates to everything that humans do and b) it has become an effective way to market products. Selling stuff to the masses drives the economy (consumer spending historically [21] constitutes around 65% - 70% of U.S. GDP), though such rampant consumerism ironically has a largely negative impact on sustainability. You may recall that EM SC 240N was largely designed to cut through a lot of this "sustainababble," and help you understand what sustainability really means. This course will offer a review of a lot of the concepts in that course, as well as provide some additional ones.

See below for a summary of key sustainability points from Lesson 1 of EM SC 240N:

- There is no single, universal definition of "sustainable," "sustainability," or "green." This lack of definition allows for the ubiquitous use noted above. There is no authority that monitors and/or limits the terms' use, and thus it can be attached to nearly anything. That stated, there are a few important definitions/conceptualizations that you should know:

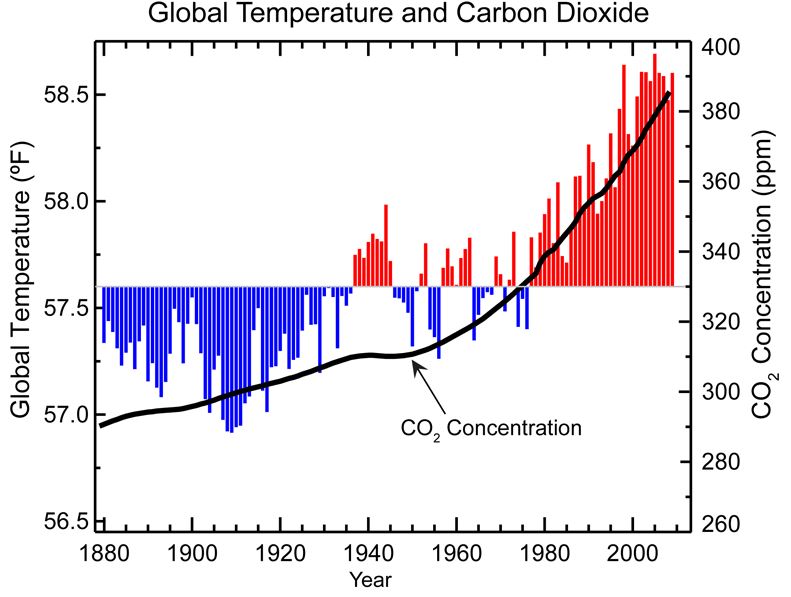

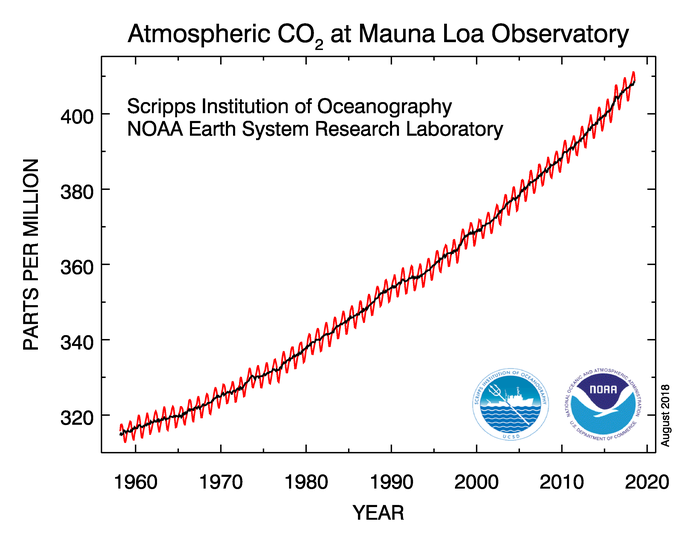

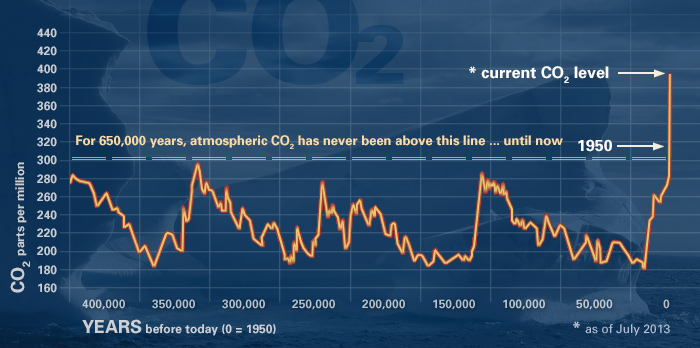

- If something cannot be done for at least the foreseeable future, then it should not be considered sustainable. The example of sustained yield management used in EM SC 240N is useful here: If trees (or any naturally replenishing resource such as fish, freshwater, soil nitrogen, etc.) are harvested faster than they can be replenished, then they are not sustainable. On the flip side, if a waste product is being emitted faster than it can naturally be reabsorbed by the environment, it is not sustainable. Rising CO2 levels are a good example of this - the earth cannot absorb carbon dioxide at the rate it is being emitted by humans.

- The most universally recognized definition of sustainability (technically it is the definition for sustainable development, but the terms can generally be used interchangeably) is from the so-called Brundtland Commission, which was the United Nations committee headed by Gro Harlem Brundtland that published Our Common Future in 1987. Their definition is that sustainable development "meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs" (Credit: Is Sustainability Still Possible? p. 3. Original source: Our Common Future [22], World Commission on Environment and Development).

- There are many other helpful definitions of sustainability. One that I think is particularly robust is from the U.S. EPA [23]: "To pursue sustainability is to create and maintain the conditions under which humans and nature can exist in productive harmony to support present and future generations."

- Front and center of the Brundtland Commission's definition is intergenerational equity, a very important concept in sustainability. Intergenerational equity mandates that we consider the impacts of our actions on future generations. This expands the basic concept of sustainability (Can we keep doing what we are doing indefinitely?) to include whether or not we are promoting a good quality of life for future generations. Not only should future generations survive, but they should thrive.

- Achieving intergenerational equity is fraught with difficulty. What is a need? To what degree do we sacrifice the needs and wants of the current generation in order to maximize the chances of future generations to live a good quality of life? How can we know the exact impact on the future? Though these are difficult questions to answer, true sustainability requires that we address all of them.

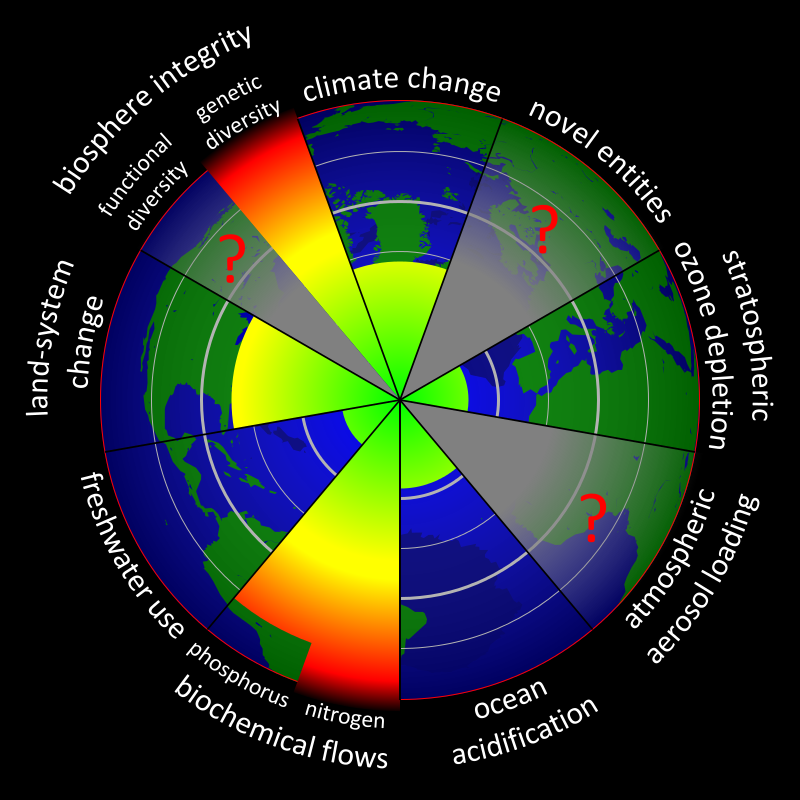

- Sustainability metrics/indicators help get rid of some of the "fuzziness" of sustainability definitions. Indicators quantify things that impact sustainability so that we can ascertain whether or not we are on a sustainable path, e.g. the number of resources remaining, the concentration of wastes, rates of consumption, population trends, etc. This is addressed in more detail in other lessons, but atmospheric CO2 levels are a good example of this (see below).

- Systems thinking is another essential concept in sustainability. The following is from EM SC 240N:

- There is difficulty in satisfying both present and future needs. Ridding the world of abject poverty is at the forefront of sustainability goals, but unfortunately economic growth and sustainability - particularly environmental sustainability - are often at odds. For example, increasing access to fossil fuels generally helps facilitate improving economic conditions, but causes unsustainable emissions. Even current and future sustainability can be at odds, e.g. when Engelman notes that: "Safe water may be reaching more people, but potentially at the expense of maintaining stable supplies of renewable freshwater in rivers or underground aquifers for future generations."

- This all indicates the importance of systems thinking. There is a lot of literature about systems thinking, and it does not have a single definition. (If only the world of sustainability were so simple!) It can be thought of as analyzing the world around us as a collection of interrelated systems, and not considering phenomena as isolated and unrelated to other phenomena. In other words, systems thinking requires consideration of connections.

- There is an old saying that "the biggest cause of problems is solutions," which is important to keep in mind when analyzing sustainability issues. From a sustainability perspective, systems thinking means that you should at least always a) consider the short- and long-term impacts of actions, both in space and time, and b) consider the possible causes of issues. It is unwise to address a problem or situation without thinking about the possible causes and consequences.

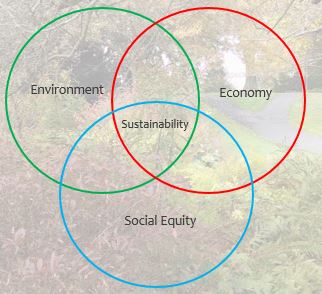

The Three Es of Sustainability

Sustainability and sustainable development are often thought of as having three core components: environment, economy, and equity. These are commonly referred to as the "3 Es" of sustainability. The 3 Es is a useful way to provide an analytical framework for sustainability. This 3E framework is useful because it provides questions that can be asked when investigating whether or not something is sustainable. While even these terms can be defined in various ways, we will use the following definitions from the reading when analyzing the sustainability implications of something:

- Is it "environmentally sustainable, or viable over the very long term"? (environment)

- Is it "economically sustainable, maintaining living standards over the long term"? (economy)

- Is it "socially sustainable, now and in the future"? (social equity)

The following provides a few more details about each of the 3 Es:

- The environment is the least confusing of the three. If we can keep doing ___________ without compromising the integrity or functioning of the environment (e.g. by not emitting wastes faster than they can be absorbed and not using natural resources faster than they can be replenished), then it can be considered environmentally sustainable. Later in this course, we will go over the concept of regenerative sustainability, which refers to taking this a step further and improving natural conditions.

- Equity refers to the fairness of opportunity and access to resources like education, health care, a clean environment, political participation, social standing, food, shelter, and others. It does not mean equal distribution of resources. There will always be inequality, whether we want it or not. In a socially equitable society, everyone has reasonable access to things that are generally considered conducive to a good quality of life. Whether or not they take advantage of them is another story. There is an important difference between being uneducated because of laziness and because of lack of access to good schools. Making this happen is easier said than done, but the distinction is important to make.

- Economic sustainability refers both to a) engaging in actions that are economically sustainable (if businesses do not make enough money to continue, they will not be in business for long) and b) promoting an economy that provides and maintains a reasonably high quality of life for all over the long term. From a sustainability perspective, money should be seen as a means to an end, and that end should be quality of life and environmental sustainability. If I run a business that makes me a lot of money but negatively impacts the quality of life for current and/or future generations, it is not considered economically sustainable from a 3E perspective.

Energy, Sustainability, and Society

I have a challenge for you: think of something that you did in the past week that did not involve energy.

Okay, so that's not really a fair challenge. Everything we do, even thinking about things that we might do, requires energy. Here's a more reasonable challenge: think of something that you did in the past week that did not involve the use of non-renewable energy.

Any food you eat almost certainly required non-renewable energy. There are obvious connections like farm machinery, artificial fertilizers, and herbicides, transporting food, refrigerating food, cooking food, and packaging food. But even if you grow your own, you likely used a tool or fencing that was manufactured using non-renewables, seeds that were processed and shipped with fossil fuel-using machines, packaging that was made using non-renewable energy, or maybe even plastic row markers made with petroleum-based plastics. Almost all transportation uses non-renewables, most businesses run on non-renewable energy sources (either directly or indirectly through electricity generation), almost all of the products you buy contain materials either made of or that are processed with fossil fuels. The electronic device you are looking at right now is partially made of and manufactured using fossil fuels. In short, modern society is very dependent upon access to non-renewable energy, particularly fossil fuels. As Asher Miller notes in The Post Carbon Reader:

Look around and you'll see that the very fabric of our lives - where we live, what we eat, how we move, what we buy, what we do, and what we value - was woven with cheap, abundant energy. (p. xiv)

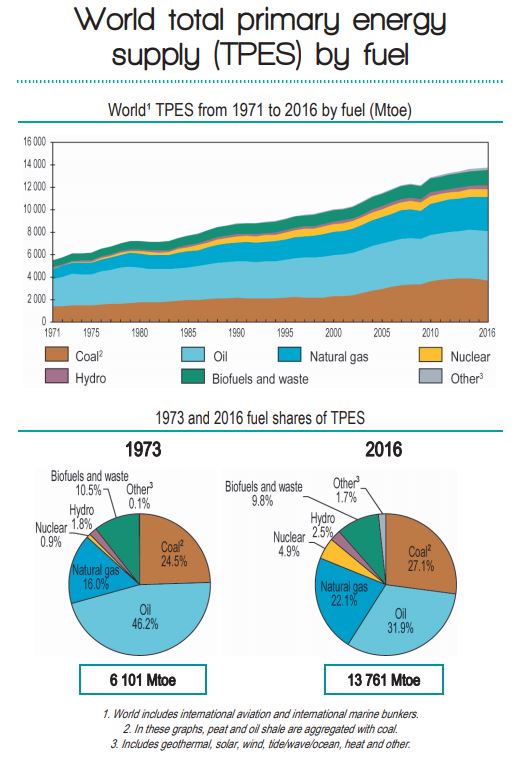

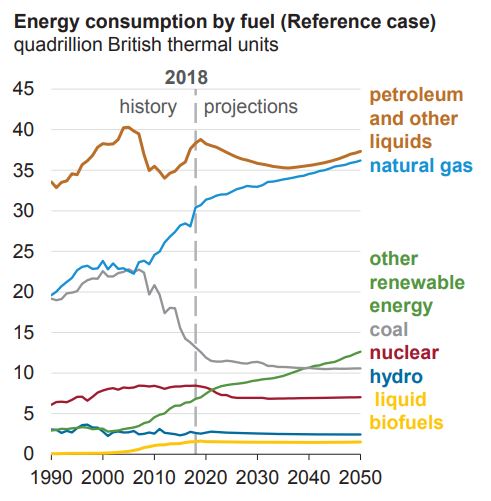

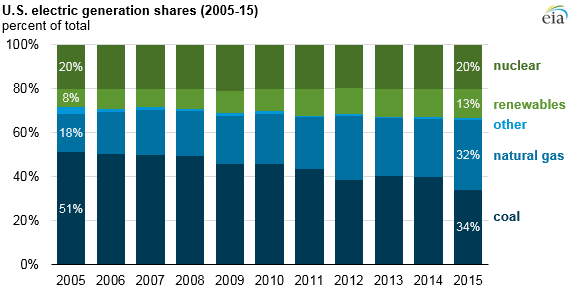

The charts below provide some insight into the U.S. and global energy regimes. The first chart is from the International Energy Agency, and the other is from the U.S. EIA. Both are excellent sources of energy information. Please take a look at them and read through the descriptions, and keep in mind that there is one final summative point provided below.

Global Energy Use

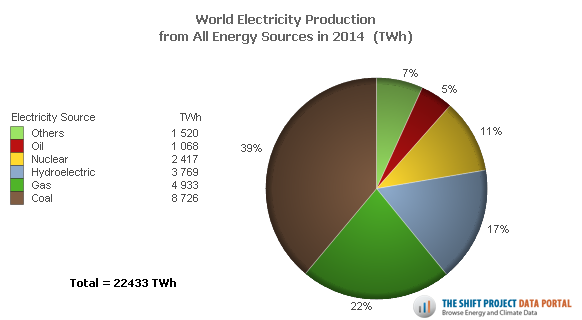

There are a few interesting things to point out from the chart above.

- These charts provide what is referred to as an energy fuel mix. The term "fuel mix" refers to the percent breakdown of energy sources for a given area or sector.

- Total Primary Energy Supply (TPES) refers to all original or primary energy consumed. For example, if your electricity is supplied by a power plant, the energy your electronic device is using right now is not primary energy because the electricity was converted from an original source (e.g. coal, oil, natural gas, nuclear). Given that electricity generation is always less than 100% efficient (sometimes much less, per the previous section), the primary energy used by your device is greater than what shows up on your electric bill.

- Biofuels are lumped together with "waste." In many parts of the world, including many states in the U.S., if you burn garbage to produce heat and/or electricity, it is considered a biofuel, and thus renewable.

- Wind and solar are lumped into the "other" category, at a measly 1.5%. This has improved since 2015 (and was 1.1% of the total in 2012), and in fact has been growing at an all-time high rate, but there is still a long way to go before wind and solar make a major dent in the global energy regime.

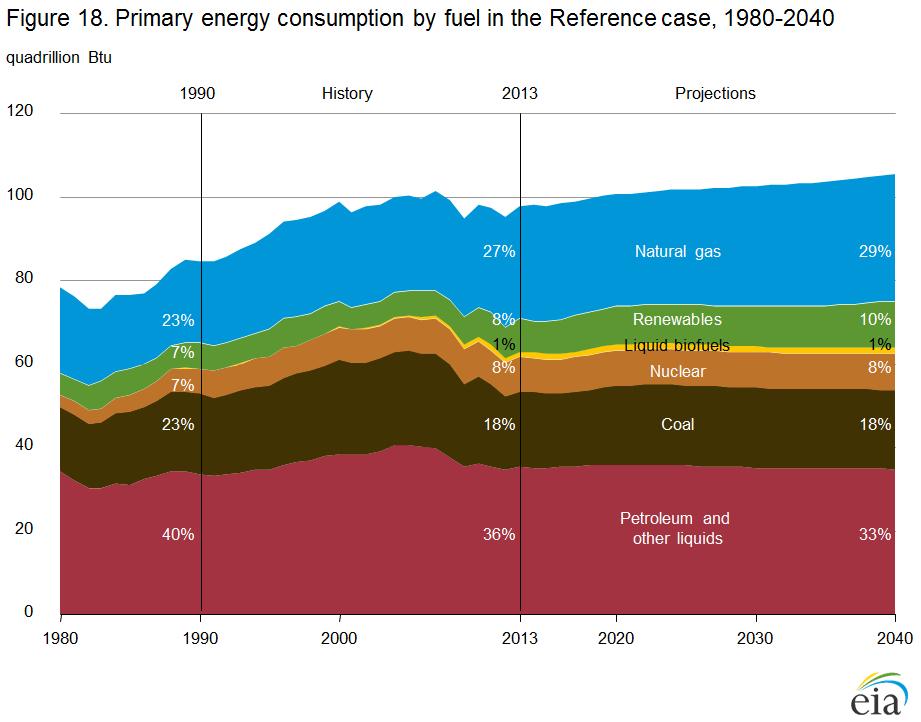

U.S. Energy Fuel Mix

The charts below provide rather dramatic evidence of how important non-renewable energy is to the U.S. Both charts are from the EIA's Annual Energy Outlook (AEO) series, which are published on a yearly basis. A few things worth pointing out:

- The first chart is from the 2015 version of the AEO. Though a bit outdated, I put it here because the chart style (distinct color-coding and percentages) makes it very easy to see the dominance of non-renewable energy sources. The second chart is from the most recent report but is not quite as easy to interpret.

- These charts include both historical use and projected future use. Any way you slice it, the charts make clear that non-renewable energy (in particular fossil fuels) has played, and will (likely) continue to play, a dominant role in society.

- Aside from recessions (e.g., the early 1980s and 2007-8), energy use continues to increase over time. Despite consistent increases in energy efficiency, the U.S. can't seem to level off, never mind reduce overall consumption. This is also something that will have to be addressed if we are going to have a sustainable energy future.

Final Thought on Energy and Sustainability

It should be clear that the vast majority of energy used worldwide comes from non-renewable sources, and this is unlikely to change any time soon. This has a lot of sustainability implications, which we will address in more detail later. From systems thinking perspective, it is important to realize that everything you do requires energy, and it is important to think about where that energy comes from and what the sustainability implications are.

Summary and Final Tasks

Summary

That's it for Lesson 1! Hopefully this review helped solidify these concepts for you. By now you should be able to:

- provide a basic description/definition of the following terms/concepts: energy, thermodynamics, the First Law of Thermodynamics, energy efficiency, renewable energy, non-renewable energy, carbon free, carbon neutral, sustainability, Brundtland Commission, 3 E's, intergenerational equity, and systems thinking;

- identify examples of the above concepts in contemporary culture;

- apply the above concepts in analyses of contemporary issues;

- identify and describe different forms of energy;

- describe how energy can be converted from one form to another; and

- analyze energy-focused charts and graphs.

Reminder - Complete all of the Lesson 1 tasks!

Double-check the to-do list on the Lesson 1 Overview page [28] to make sure you have completed all of the activities listed there before you begin Lesson 2.

Lesson 2: EM SC 240N Lesson 2 Review

Overview

The purpose of this lesson is for you to review key concepts from Lesson 2 (Fundamental Sustainability Considerations) in EM SC 240N. I strongly encourage you to at least browse through Lesson 2 [29] of EM SC 240N, though that is not required.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- define and provide examples of negative externalities;

- analyze the implications of achieving a steady state economy, and how they relate to ecological footprint.

- identify the pros and cons of energy return on energy invested;

- describe the (in)adequacies of using GDP as a development metric;

- analyze the viability of various development metrics;

- define social and environmental justice;

- identify examples of social and environmental (in)justice.

Lesson Roadmap

| To Read | Lesson 2 Online Content | You're here! |

|---|---|---|

| To Do |

|

|

Questions?

If you have any general course questions, please post them to our HAVE A QUESTION discussion forum located under the Discussions tab in Canvas. I will check that discussion forum regularly to respond as appropriate. While you are there, feel free to post your own responses and comments if you are able to help out a classmate. If you have a question but would like to remain anonymous to the other students, email me through Canvas.

If you have something related to the material that you'd like to share, feel free to post to the Coffee Shop forum, also under the Discussions tab in Canvas.

Externalities

Externalities is one of the more nuanced concepts from EM SC 240N, so I am giving it its own page. This is mostly a summary of EM SC 240N's version.

At this point, I'm sure you are all familiar enough with basic economics to know these three fundamental principles:

- All else being equal (this is known in economics as ceteris paribus [30]), as the demand for something in a market economy increases, the price increases, and when the demand decreases the price decreases.

- All else being equal, as the price of a good increases, the demand decreases, and if the price goes down, demand increases.

- Economic actors buy and sell things based on a cost-benefit analysis. They consider the private utility (the benefit to them) and the private cost (the cost to them) and engage in the transaction if they deem the cost-benefit balance to be in their favor.

The first two are not very controversial - if very few people want something (it has low demand) then it makes sense that companies would need to drop the price to sell it, and if something is in high demand, a company can charge more. Also, as the price of something rises, it makes sense that fewer people would want (or be able to) buy it, and vice versa. (It should be noted that some goods can be "inelastic" to a certain degree, which means that a price increase does not reduce demand by much and/or a price drop does not increase demand by much. Oil [31]can be inelastic under certain conditions, for example.)

The third point makes a lot of sense, too. If I go to buy apples and I go to the grocery store and see two different brands of the same apples (probably Honeycrisp, since my kids are obsessed with them) side-by-side, but one is cheaper than the other, I'll probably buy the cheaper one. The same type of decision-making process goes into most economic decisions that you make, whether it involves clothes, cars, where to go out to eat, which detergent to buy, which cell phone to purchase, and so on. You ask yourself: "Is it worth it to buy this product or that one?" and this is based on the price combined with the perceived value of the good. This lies at the heart of modern economic models.

Thus, the price of something is an essential consideration in how much of it is used, and thereby produced. But how is the price determined? In simplified terms, all of the costs that go into getting the product to the end user should be reflected in the price. For my Honeycrisp apple, the costs of at least the following should be included: the farm (paying for seeds, workers, growing equipment, etc.), the company that shipped the apple to the store (paying for workers, fuel to drive the trucks, people to arrange logistics, etc.), and of course the grocery store (paying workers, electricity bills, paying investors, insurance, etc.). These and any other costs associated with getting the apple to you should be covered. Otherwise, the businesses lose money and won't be able to stay in business much longer. In sum, all of the costs to get the good to you should be included in the price. Seems pretty straightforward, right?

As you may remember, it is not always this simple. All of the apple-related costs included in the price that was noted above are internalized, that is, they are reflected in the price. But can you think of any externalized costs, that is, costs that are not reflected in the price? Examples may include:

- If the apple is not organic, the workers may get sick from the chemicals, which costs them medical bills and lost work.

- If the farm sprays a lot of pesticides, this could harm local bee populations, which in turn reduces other crops that rely on bees to pollinate.

- The fuel used to ship the apples emits CO2, which contributes to climate change, and other pollutants such as particulates, which cause health problems and associated costs.

- The electricity used to power the grocery store may have been generated by burning coal, which has similar impacts to the gas or diesel noted above.

There may also be some external benefits involved with the process of getting the apple to you. Possible examples include:

- The tree absorbed CO2 and some pollutants from the air, reducing the damages noted above. (It should be noted that this would likely be lower than the amount emitted by the truck and the power plant noted above.)

- The trucking job provided enough income for the worker to go to school and eventually get a higher-paying job with better benefits.

- The money paid to the grocery store helped it stay in business, which contributed to the viability of the community around it.

There are many more possible impacts that are not included in the price of the apple. All of these would be considered externalities, as long as they were not included in the cost. The OECD offers a reasonably good, concise definition of externalities:

Externalities refers to situations when the effect of production or consumption of goods and services imposes costs or benefits on others which are not reflected in the prices charged for the goods and services being provided

(Please note that some economists consider anything that happens to someone that was not directly involved in a transaction an externality whether or not that "anything" is included in the price. In this course, we will only consider it if it is not included in the price.) Before moving on, feel free to watch the video below. The most relevant parts are the first 3:20 of the video and 5:06 - 6:22.

OPTIONAL video

Externalities occur when costs or benefits accrue to a person, or persons, who are not involved in the decision-making process. Note that externalities can involve either third-party costs (this would be a negative externality) or third-party benefits (this would be a positive externality). Let's address each of these in turn.

Negative externalities occur when a decision or activity imposes costs on anyone not involved in making that decision. Think of it this way: every decision involves some cost to the decision-maker; that's the private cost of your choice. But sometimes the decision imposes costs on others as well, which would be the external cost. Social cost, then, is the total cost to all members of society, or the sum of the cost to the decision-maker (which is private cost), and to others (external cost). What this means is that if a decision imposes any kind of external cost, then the social cost will exceed the private cost.

Think about this: do you think that too many people use their cell phones while driving, or too few? Well, why do you think that is? The answer lies with this notion of externalities. Look at it this way: when you're deciding whether or not to get on your cell phone while you're driving, what are the private costs, i.e. the costs to you, the decision-maker? Perhaps the cost of buying a cell phone in the first place? Or maybe the minutes you'll be using, or the cost of sending a message? It might even occur to you that you're increasing the likelihood of you getting into an accident. Now, are there any costs to other people, people who have no control over your decision to use your phone while behind the wheel? What about the increased risks to them? Or even just the annoyance of you driving like an idiot because you're on the phone? These are the external costs or the costs you impose on others with your behavior.

In the end, this discrepancy between the cost to you and the cost to society (which is the sum of the private and the external cost) leads to overproduction, if you will, of people driving while on their cell phones. Why? Because we’re all rational decision-makers – using the cost to us and the benefits to us to make our decisions. Very rarely do you find someone who includes costs to others when weighing a private decision. Essentially, you make the decision to be on the phone while driving because you consider only part of the cost - the cost to you. With negative externalities, because the private decision is based on costs that are too low, from society’s standpoint, the behaviors, or products, are overproduced from society's view.

This market failure provides a role for the government to correct the market, i.e., bring the production back to the socially optimal level. In the case of cell phones, this is most often done by putting laws in place that ban such behavior while driving and have hefty fines attached if you're caught. This effectively raises the cost of engaging in such behavior and thus decreases the amount of the behavior that occurs. The same idea would apply to, say, a steel factory. There's a certain private cost of producing steel (I’ll assume that on the benefit or demand-side, private and social are the same for now), but the production of steel also results in pollution, a cost to others in society. This means that the marginal social cost is greater than the marginal private cost. Left to its own devices, the steel market will be based on private costs and private benefits, yielding the price and quantity associated with equilibrium E1. What would society rather see? The socially optimal outcome would be based on social cost and social benefits, or equilibrium E2. Notice, this means society would like to see less production, meaning less pollution, and would be willing to pay a higher price to do so.

This is where the government comes in.

What is the government solution to a negative externality? Simple! Get the decision-maker to internalize the external effect. Since the problem arises from the decision-maker using costs that are too low, you need to somehow impose some additional cost, so the decision becomes based on level of social cost. This could be done by way of taxes, fines, regulation or cleanup fees. Or, in the case of pollution, there’s now a market for credits that allow you to pollute. If you're a clean producer, you’ll have unused credits you can sell which is an incentive for cleaner production. If you create a lot of pollution, you’ll need to acquire extra credits to continue producing, which is also an incentive to cut back on pollution production.

What about positive externalities? Just as you can make choices that impose costs on others, you can also make choices that result in benefits to others. If this is the case, then social benefits equal the private benefits, or benefits to the decision-maker, plus external benefits, or benefits to others. In the case of a positive externality, social benefits exceed the private benefits. Take education, for example. YOU decided to continue your education; why is that? What are the benefits to you of making this decision? It might just be the love of learning, or because you know that education means a better, higher-paying job in the future. But what about society? Society as a whole benefits from having a better-educated populace; highly educated, highly-skilled workers tend to be innovators, which helps keep our economy moving forward. All of this is good except for the fact that, in a free market, education will be underproduced -- this is true of any positive externality.

Why? Because the private decision-maker doesn't see the full benefit of education that society sees, so not as much education is produced. For the consumer of education, there's a certain private benefit (I’ll assume private cost and social cost are going to be the same). Decision-making based solely on private costs and benefits results in equilibrium at E1. Society as a whole sees a greater benefit; if the equilibrium were based on social costs and social benefits, equilibrium would occur at E2. Society desires a greater level of education, and is willing to pay more to achieve it. From a social standpoint, in a free-market, education will be underproduced. What's the government solution to a positive externality? Well, get the decision-maker to internalize the external effect. Sounds familiar, doesn't it? Except that with the negative externality, we had to try to get the decision-maker to see higher costs; with a positive externality, the government needs to somehow make the decision more beneficial to the private decision-maker. In the case of education, the government may provide grant money, low-interest loans, or tax credits in order to provide added incentive to get more education.

As noted in the video, there are usually external costs and/or external benefits to transactions. External costs and benefits are borne by people or other entities that had no input on the transaction and were not fully included in the price. A negative externality occurs when an external cost occurs, and a positive externality occurs when an external benefit occurs.

Sustainability Implication

There are a few important sustainability implications of externalities:

- Negative externalities are very common, and often impact sustainability. Pollution is a prime example of this. It is rare that all of the costs of pollution are included in the price of something, whether it is mercury, sulfur dioxide, or particulates emitted from a power plant, CO2 emitted from a car's tailpipe or fertilizers that run off of farms and cause dead zones. These can all have major negative sustainability impacts.

- Negative externalities are overproduced because they make the price lower than it should be. If the negative impacts of climate change were included in the cost of coal-fired electricity, for example, the cost of coal-based electricity would be higher and the demand for it would diminish.

- Positive externalities are underproduced because they make the cost lower than it should be. If all of the benefits of say, education were included in its price, the price would be lower and thus in higher demand.

- In a broader context, economics plays such an important role in modern society that externalities have become a major problem.

In sum, externalities are by definition not included in the cost of goods. Positive externalities, which are usually good for sustainability, do not occur as often as they should because the benefit is not included in the price. Negative externalities (which are more common, by the way) happen more often than they should because their cost is not included in the price.

The Social Cost of Carbon

Without getting into the specifics about the probable causes of climate change (that will be covered in the next lesson), let's take a look at climate change as an externality. As you will see in the next lesson, if the climate continues to change, the impacts will be overwhelmingly negative. Quantifying these costs is an active area of research, but many countries - including the U.S. - have placed an "official" cost on the emission of carbon dioxide (this is used to calculate the cost of new legislation). Under the Obama administration, the U.S. federal government used a social cost of carbon (SCC) of $39 per tonne [32]of carbon dioxide. (Not surprisingly, the Trump administration has proposed to lower this significantly.) A 2015 study out of Stanford University [33] found that the U.S. grossly underestimated the SCC and that it should be closer to 220 dollars/tonne. In 2013, major corporations integrate the cost of carbon emissions into their projects [34] (between 6 dollars and 60 dollars/tonne), though they use some different considerations than SCC, and by late 2016 hundreds of companies [35] worldwide had integrated SCC internally.

Summary

There is a lot of material to these points and it is very important, so here is a summary of the key points:

- An externality is a cost or benefit of the production or consumption of a good or service that is not included in the private cost/benefit of that good or service.

- An external cost (e.g. pollution) not included in the price is a negative externality. An external benefit (e.g. education) that is not included in the price is a positive externality.

- If all external costs and/or benefits are included in the price, then most economists believe that no externality has taken place.

- Goods and services with negative externalities tend to be overproduced, meaning that more is produced than is socially optimal. This is because the private cost of the good/service is less than the total (social) cost, i.e., it is cheaper than it should be.

- Goods/services with positive externalities tend to be underproduced because the total (social) benefit is higher than the private cost, i.e., it is more expensive than it should be.

- The direct short-term external costs of energy generation can be significant, due to health problems and other issues. In other words, if external costs were included in the price of fossil fuels, they would be more expensive. However, in some emerging economies, these external costs may be overcome by the positive benefits of having more energy.

- Climate change is considered a negative externality because the impacts of emissions are felt by people that did not cause the emissions. Most of these costs are in the future.

- The social cost of carbon (SCC) is an attempt to quantify the external cost of emitting CO2. This is very difficult to do but has been quantified in terms of dollars per tonne of emissions. By using dollar per tonne, the cost of a kWh of electricity, a gallon of gasoline, ccf of natural gas, etc. can be calculated.