Lesson 3: EM SC 240N Lesson 3 Review

Overview

The purpose of this lesson is for you to review key concepts from Lesson 3 (Critical Thinking and Specific Sustainability Issues) in EM SC 240N. I strongly encourage you to at least browse through Lesson 3 [1] of EM SC 240N, though that is not required.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- analyze the credibility of information sources;

- identify characteristics of the Anthropocene;

- explain how the greenhouse effect increases the average surface temperature of the earth;

- identify evidence for anthropogenic climate change;

- identify characteristics of the 6th Mass Extinction;

- explain the benefits of biodiversity;

- analyze the sustainability impacts of freshwater availability; and

- apply the precautionary principle to sustainability considerations.

Lesson Roadmap

| To Read | Lesson 3 Online Content | You're here! |

|---|---|---|

| To Do |

|

|

Questions?

If you have any general course questions, please post them to our HAVE A QUESTION discussion forum located under the Discussions tab in Canvas. I will check that discussion forum regularly to respond as appropriate. While you are there, feel free to post your own responses and comments if you are able to help out a classmate. If you have a question but would like to remain anonymous to the other students, email me through Canvas.

If you have something related to the material that you'd like to share, feel free to post to the Coffee Shop forum, also under the Discussions tab in Canvas.

Critical Thinking and Critiquing Information Sources

Critical Thinking

There has never been a time in human history where such a massive quantity of information is readily available to most people, but the ease with which information can be shared has led to an abundance of questionable information. As the adage goes, "You can always find someone that agrees with you on the Internet" (okay, maybe that's not an actual adage, but you have to admit it is difficult to disagree with it.) At any rate, enter critical thinking, an essential skill to have in our modern information-overloaded world.

Feel free to read through The Foundation for Critical Thinking [2]'s definition of critical thinking (here) [3]. The summary is as follows:

- Critical thinking requires a skilled evaluation of information using all manner of analytical and observational tools at your disposal. Regardless of what you are analyzing, you should use the same or similar set of skills. Critical thinking transcends the subject material.

- Critical thinking requires self-evaluation of what you know and do not know, your assumptions, the scientific basis of the problem at hand, and an analysis of the results. One aspect of this is looking at issues from viewpoints different than your own, to the extent possible.

- Critical thinking requires more than just "knowing things" and having information processing skills. You must apply this knowledge and these skills, and accept the results, whether they are the results you had hoped for/expected or not.

- If you are seeking selfish (subjective) motives, you may be able to think critically, but the results will usually be flawed. You must approach the issue with "intellectual integrity," which really refers to the above three points (thorough analysis and acceptance of the results).

- No one knows everything, and everyone is subject to bias by virtue of being limited in knowledge and experience. You can be an extremely skilled critical thinker but are limited by your knowledge and experience of the topic at hand. The best critical analysis may arrive at an incorrect conclusion due to this. The flip side of this is that the more you know about, experience, and objectively analyze a piece or type of information, the more likely you are to arrive at a sound conclusion. As stated in the article: "The development of critical thinking skills and dispositions is a life-long endeavor."

They also provide a good approach to critical thinking:

A well cultivated critical thinker:

- raises vital questions and problems, formulating them clearly and precisely;

- gathers and assesses relevant information, using abstract ideas to interpret it effectively;

- comes to well-reasoned conclusions and solutions, testing them against relevant criteria and standards;

- thinks open mindedly within alternative systems of thought, recognizing and assessing, as need be, their assumptions, implications, and practical consequences; and

- communicates effectively with others in figuring out solutions to complex problems.

Credit: The Foundation for Critical Thinking [3]

I am asking you to apply these principles as much as possible. Keep an open mind, and try to analyze information using evidence, logic, reason, and with an eye on alternative viewpoints. Try to recognize the limitations of your knowledge, and attempt to be self-critical with regards to biases and limited worldviews that you have. Embrace discussion with others, and try to approach discussions with the intent of learning from each other to come to a reasonable conclusion, not to convince the other person that you are correct.

Critiquing Information Sources

In addition to critical thinking, assessing the quality of sources of information is an important part of determining whether or not the information is reliable. Though there is no universal method of doing this, with some practice (and knowledge) you can usually determine source validity with relative confidence.

Optional Reading

- "Harvard Guide to Using Sources [4]." Feel free to read through the entire webpage, but the key tabs for our purposes are "Questions to Ask About All Sources," "Evaluating Journal Articles," and "Evaluating Web Sources."

Here are some general and additional tips for analyzing sources:

- Always consider the author's credentials. This is not the only thing to look at, but it is an important element. All else being equal, someone who has spent many years analyzing a subject or has advanced training is more likely to be reliable than someone with thin credentials.

- Be careful when using a source that is expressly opinion-based, e.g., in the Opinion pages of the newspaper (hard copy or online). An opinion is not necessarily wrong - there are certainly such things as "well-informed" opinions - but you should not use this as an academic reference. Opinions from people you trust are a great way to learn things, but you should not use them as unvarnished truth. Always seek to corroborate the information provided.

- As indicated by the Harvard articles, I strongly suggest corroborating factual information presented in the article elsewhere (in general, not just for opinions).

- As indicated in a previous lesson, peer-reviewed journals are generally the most reliable information sources. When not peer-reviewed, consider where the factual information came from. Often, non-peer reviewed articles use data from peer-reviewed sources. You should always try to find the original material if possible.

- Related to the previous point, always consider where the author got their information from (check their sources!).

- Currency is important for some sources (especially for things like technology), but for others, it is less important (e.g., historical events, foundational theories). Use your best judgment.

- If you don't know already, do some research on the author of the article. Use Google to your advantage! You can search "<author or organization's name> bias" or "is <name> biased," etc. I strongly suggest searching for other articles/websites published by the author/organization. Oftentimes, you can click on the author's name on the website and it will link you to other articles written by them. Scan through them and see if a consistent bias (or at least worldview) is presented. It will often become obvious if someone holds a certain political/social viewpoint.

- The same advice as the previous point goes for the site owner - look through articles published on the website, and try to figure out if a one-sided viewpoint is presented. All that said, keep in mind that just because someone holds a certain worldview does not mean that the information is unusable (complicated, I know!). There are many reliable information sources (people and organizations) that hold a certain worldview. You should consider the other aspects of the information, particularly the objectivity. Also, keep a lookout for consistently extreme viewpoints.

- Do NOT take a website's self-description as proof of its objectivity. I wish it were that easy! Even the most biased of sources want you to believe that they are unbiased.

- Just because a website is a ".org" and not a ".com" does not mean it is unbiased. In fact, the type of organization is pretty meaningless. There are a lot of biased non-profits out there.

When analyzing sources in this course, I'll ask you to do the following things:

- The most reliable type of information is taken directly from a peer-reviewed article. If you pull your information directly from such an article, you just need to state the journal and the author, then provide some information about the author, per the next step.

- Analyze the author's credentials. Are they an authority on the subject? Do they have years of experience and/or an advanced degree in the topic? Are they a well-respected writer? Have they won journalism, academic, etc., awards?

- Consider the objectivity of the way the information is presented. Is it matter-of-fact/objective or does it use sensational/emotional language? Does the author appear to inject opinion and/or use language that tries to get an emotional response?

- Consider the objectivity of the site the information is on. Investigate other articles on the website to see if there appears to be an agenda.

- Reliability. Can you find other reliable sources that have the same information? Corroborate the information.

Overall, understanding the reliability of sources gets easier with time. The keys are a) to keep reading and paying attention to other information sources, b) to constantly investigate the reliability of sources, and most importantly c) learn as much as you can! The more you do this, the more you will develop a "bias detector," so to speak.

The Anthropocene and Biodiversity

Living in the Anthropocene and Recognizing Planetary Boundaries

To Read Now

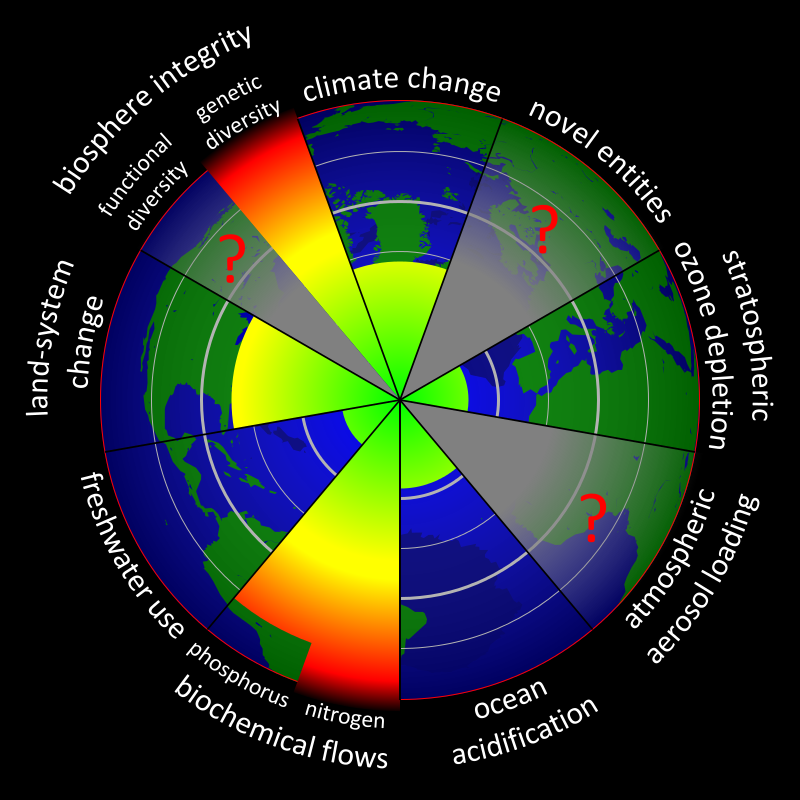

- Skim through the most up-to-date status of the 9 Planetary Boundaries [5]. This link takes you to the Stockholm Resilience Center, which is where the 9 Planetary Boundaries concept originated. (Not required, but you can access a downloadable, resizeable image of the Planetary Boundaries here [6].)

- "Ecosystem Services [7]." National Wildlife Federation.

- (Optional) Read pp. 19 - 22 of chapter 2 of Sustainability Still Possible?. "Respecting Planetary Boundaries and Reconnecting to the Biosphere." This is located in the Module tab in Canvas, under Lesson 3.

- (Optional) Feel free to read through some critiques of the 9 Planetary Boundaries concept, as well as responses from the authors [8]. This is not required, but it is enlightening if you are interested in this concept. (Access a .pdf version of these critiques/responses [9], in case you cannot access the previous link.)

The following is a summary of some key points from the readings:

- The National Wildlife Federation [10] defines an ecosystem service as:

"any positive benefit that wildlife or ecosystems provide to people."

Examples include plants that convert carbon dioxide into oxygen, fisheries that naturally replenish themselves and feed humans, wetlands that filter toxins and mitigate storm impacts, soil organisms that foster plant growth, and bees that pollinate food crops and other plants. We could cite innumerable examples, but without ecosystem services, life on earth would not be possible. Further, much of what we depend on for survival is offered for free by nature. Most ecosystem services are performed by the biosphere, which "includes all living organisms on earth, together with the dead organic matter produced by them." (Credit: Encyclopedia of Earth [11]).

- Folke starts out with a brief discussion of the biosphere, which is "the living part" of the area on and near the earth's surface.

- He points out that humans have become "a dominant force in the operation of the biosphere."

The time that we find ourselves in now is what he terms the "Anthropocene," which he defines as "the age in which human actions are a powerful planetary force shaping the biosphere."

- Note that the term "Anthropocene" is well-known in scientific circles - Folke is nowhere near alone in using it! Regardless, the unprecedented success of the human species during this time has "to a large extent...been enabled by the human ability to draw on the functioning of the biosphere." He notes that ecosystem services (e.g., "fertile soils, storm protection, and sinks for greenhouse gases and other wastes") have played an essential role in humanity's success.

- He points out that there have been many positive benefits to people, but that we are overburdening the biosphere and risk "undermin(ing) the capacity of life-supporting ecosystems to...provide the essential ecosystem services that human well-being ultimately depends on."

- If we humans are to continue the success that we have realized in the past few thousand years, he believes that we need to work on reducing our ecological impact to the point that ecosystems can continue to thrive and provide essential services. In order to do this, he points to the need to measure our impact in "critical biophysical processes in the Earth's system." These are termed the "nine planetary boundaries."

- The nine planetary boundaries provide metrics that can be analyzed to determine if humans are overusing ecological capacity. They are called "boundaries" because they represent indicators of when we have crossed into dangerous territory. He is careful to point out that there is some uncertainty with some of the boundaries, but that they provide the best scientific analysis of whether or not humanity is operating within safe ecological limits.

[12]

[12]

Why call it the Anthropocene?

So where does the term Anthropocene come from? You may remember the concept of the geologic time scale [14] from Geology or Environmental Science class, which is how the earth's history is separated into different time periods called eons, eras, periods, epochs, and ages. (Refer to this chart from the Geological Society of America [15] for details.)

The Holocene epoch began around 10,000 years ago and saw the beginning of agriculture and thus permanent human settlements. The term "Anthropocene" is a deliberate reference to the fact that humans have become such a dominant force in the world that many scientists consider it to be a new geologic epoch. "Anthro" refers to "humans" (remember anthropocentric from an earlier lesson?), which is why it is referred to as the Anthropocene.

Biodiversity

The American Museum of Natural History in New York defines biodiversity thus:

The term biodiversity (from 'biological diversity') refers to the variety of life on Earth at all its levels, from genes to ecosystems, and can encompass the evolutionary, ecological, and cultural processes that sustain life. Biodiversity includes not only species we consider rare, threatened, or endangered, but also every living thing — from humans to organisms we know little about, such as microbes, fungi, and invertebrates.

Credit: U.S. Museum of Natural History [16]

Biodiversity is the variety of life on earth, encompassing everything from the largest ecosystem to strands of DNA. It is in every living thing around us, and everything around us is part of it. I know, this all seems very poetic, and nature can be appreciated merely by virtue of its own beauty and diversity. But there are some practical, and even selfish reasons to care about biodiversity, as you will see in the readings below.

Optional Reading

- "How does biodiversity loss affect me and everyone else? [17]" World Wildlife Foundation (Note the description of ecosystem services at the bottom.)

- E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation - Introduction [18] (Please watch the video as well.)

- E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation - The Diversity of Life [19]

There are many reasons to care about biodiversity. Aside from the huge economic benefits of ecosystem services, we depend on the biosphere - and by extension, biodiversity - to sustain human life. We depend on ecosystem services for food, shelter, clothing, water, and even our oxygen. So yeah, basically everything we need to physically survive!

Life on earth is connected in innumerable ways, and compromising one part of an ecosystem - including a single organism - has impacts in other areas. Unfortunately, human activity is playing a major role in ecosystem damage, including species extinction. Wilson points out [19] that:

"Species are disappearing at an accelerating rate through human action, primarily habitat destruction but also pollution and the introduction of exotic species into residual natural environments."

Biodiversity is a key aspect of ecosystem services, and ecosystem services are essential for human survival. One thing that makes biodiversity difficult to manage is that we don't know how many species exist, and by extension do not know exactly how many are going extinct each year.

The 6th Mass Extinction

So how much danger are we in, and how do we know? As it turns out, it is possible to measure - or at least scientifically estimate - the rate at which biodiversity is dropping. As Carl Folke pointed out in Chapter 2 of Is Sustainability Still Possible?, the rate of biodiversity loss as one of "The Nine Planetary Boundaries." The metric used to quantify this loss is the background extinction rate, which is defined as the number of species going extinct every year. So, how are we doing on this front? Some recently published studies can shed some light on this issue.

Optional Reading

- "Sixth mass extinction: The era of 'biological annihilation' [20]." John D. Sutter, CNN.

- "Stanford researcher declares that the 6th mass extinction is here [21]." Rob Jordan, Stanford News, or read the full, peer-reviewed article [22].

Sutter starts out by stating: "Many scientists say it's abundantly clear that Earth is entering its sixth mass-extinction event, meaning three-quarters of all species could disappear in the coming centuries." A mass extinction event is when more than 50% of the world's species disappear in a relatively short period of time (hundreds to thousands of years), according to National Geographic [23]. There have been five mass extinction events in earth's history. The last one was around 65 million years ago when the last of the dinosaurs famously went extinct.

It's not every day that you read a serious article that quotes a knowledgeable person as stating that: "What is at stake is really the state of humanity." Alas, that is where we find ourselves on this issue. There is unequivocal evidence that populations of many species have dropped considerably since humans became the dominant species, and as the article states, the background extinction rate is probably at least "100 times what would be considered normal" (see the optional reading above for some insight on this), which may be a conservative estimate. As indicated in the article, there is some controversy regarding this issue - the Atlantic article [24] that Sutter links to provides a good, even-keeled assessment of some of them - but this primarily has to do with difficulty in determining the rate of extinction, and whether or not it should be considered a "mass extinction" or just a dangerous level of it.

Whether a true mass extinction event is happening or not, we do know that humans are causing species to go extinct at an accelerated rate for a variety of reasons, including land use change (especially food production), poaching, climate change, ocean acidification, and more. It is important to point out that it is very unlikely that we have crossed an extinction threshold from which we cannot recover, but many signs point to us risking catastrophe. There is hope, but we will likely have to take action very quickly to prevent the worst outcome(s). Before this happens, it will have to be recognized as a problem, which unfortunately is only happening very slowly.

Climate Change

Learning Objectives Self-Check

Read through the following statements/questions. You should be able to answer all of these after reading through the content on this page. I suggest writing or typing out your answers, but if nothing else, say them out loud to yourself.

First, a few important terms:

- Greenhouse effect: the term used to describe the phenomenon whereby infrared heat warms the lower atmosphere of the earth or another planet due to the gaseous content of the atmosphere.

- Enhanced greenhouse effect: This occurs when the magnitude of the greenhouse effect is enhanced by human activity, due to the emission of greenhouse gases at an unnaturally high level.

- Greenhouse gas: a gas that absorbs infrared radiation and contributes to the greenhouse effect.

- Anthropogenic: caused by humans.

- Anthropogenic climate change: the component of climate change that is believed to be caused by humans.

The following article from the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) explains a lot of the basics regarding the terms listed above.

Optional Reading

Fact 1: The Greenhouse Effect is Settled Science

The greenhouse effect is a universally accepted natural phenomenon, and carbon dioxide (CO2) is one of the primary greenhouse gases. Without it, life on earth would not be possible. The video below from NASA does the best job of succinctly explaining the greenhouse effect of any video I've found. It is not the most high-tech video out there, but don't let that distract you from the content. (For those of you who have been around long enough to remember a teacher popping a tape into a VCR player connected to one of those big CRT televisions, this may spark some memories.)

Earth's greenhouse effect greatly affects climate. See if you can describe how carbon dioxide and water vapor cause Earth's greenhouse effect. Also, see if you can describe how the greenhouse effect maintains the surface temperature of Earth.

Scientists have long known that the presence of an atmosphere keeps the surface of the planet warmer than it would be without an atmosphere. In fact, without an atmosphere, the surface of the earth would be about 30 degrees Celsius cooler than it is now. In order to understand why, we need to consider the surface of the earth and its atmosphere separately. Because there is a radiative equilibrium we know that the planet emits enough longwave radiation into space to equal the solar radiation absorbed by it. However, most of the longwave radiation that is emitted by the planet into space is emitted by the atmosphere rather than the surface of the earth beneath it. Although the surface of the earth does emit longwave radiation, only about 10 percent of this radiation passes through the atmosphere and escapes into space. The rest is absorbed by clouds and by greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

There are many greenhouse gases but the most abundant greenhouse gases are water vapor and carbon dioxide. Shortwave radiation from the Sun passes through greenhouse gases, but longwave radiation is absorbed by them. Greenhouse gases absorb longwave radiation that is emitted by the surface of the earth. Subsequently, they re-emit the energy as longwave radiation in all directions. About half of the re-emitted longwave radiation does escape into space and contributes to the planet's radiative equilibrium. About half of the longwave radiation emitted by the gases is directed back toward the surface of the earth. As a result, a continual exchange of longwave radiation takes place between the surface of the earth and the atmosphere above it. The longwave radiation contained in this exchange causes the warming effect known as the greenhouse effect.

This phenomenon is known as the greenhouse effect because, like the glass in a greenhouse, the atmosphere traps some of the energy beneath it. The greenhouse effect produces a warmer climate on earth than would be possible without an atmosphere.

In summary, water vapor and carbon dioxide allow solar energy to penetrate Earth's atmosphere but prevent much of the longwave radiation emitted by the surface of the earth from escaping to space. This trapping of longwave energy is called the greenhouse effect and enhances the surface temperature of the earth.

In a nutshell:

- Greenhouse gases (GHGs) allow shortwave radiation to pass through them, but absorb longwave radiation and re-radiate it in all directions after they absorb it. This is simply a physical property of certain gases. Nature just doing its thing.

- Sunlight is mostly shortwave radiation, so passes through the GHGs on its way toward the earth's surface.

- If the shortwave radiation is reflected on or near the earth's surface (e.g., by clouds, water, physical objects), it passes back through the GHGs, because it is still shortwave. It goes back out to space.

- If the shortwave radiation is absorbed on or near the earth's surface (e.g., by your skin, water, soil, other surfaces) then it is radiated as longwave radiation. (This is radiant/electromagnetic heat transfer that was mentioned in Lesson 1, by the way!)

- If this longwave radiation hits a GHG molecule on its way out, it is absorbed and re-radiated in all directions.

- Some of that longwave radiation (about 50%) heads back towards the earth's surface. This results in warming that would not occur if the GHGs were not in the atmosphere.

The following gases contribute to the greenhouse effect: water vapor (H2O), carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). There are a lot of details about each, but the main focus of anthropocentric climate change is carbon dioxide and methane because they play the largest role in the climate impact that most scientists believe humans are having.

Note that methane is considered approximately 30 times as powerful [26] as carbon dioxide in terms of causing increased warming (over a 100 year period). Methane is the primary component of natural gas and is what gives natural gas its energy. If natural gas is burned, it releases about half as much CO2 as if you burn an equivalent amount of coal. But if natural gas leaks or is otherwise emitted, it is about 30 times more potent than carbon dioxide. Despite this, carbon dioxide reduction is the main focus because it is far and away the biggest contributor to anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions impact.

Fact 2: Carbon Dioxide Levels are Increasing Due to Human Activity

There are a few fundamental things to know in regards to the carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere.

- First, the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere is measured in parts per million (ppm). A concentration of 1 ppm means that there is one unit of mass of fluid for every million units of mass of the enveloping fluid. The current concentration of carbon dioxide is a little more than 400 ppm [27]. (FYI, this means that if you took 1 kg of air, there would be about 400/1,000,000 kg, which is 0.0004 kg or 0.4 g of CO2 in that kg of air.)

- Second, the atmosphere is considered the same everywhere you go on earth. Localized variations occur, but the current CO2 concentration s considered to be effectively the same no matter where you are on earth.

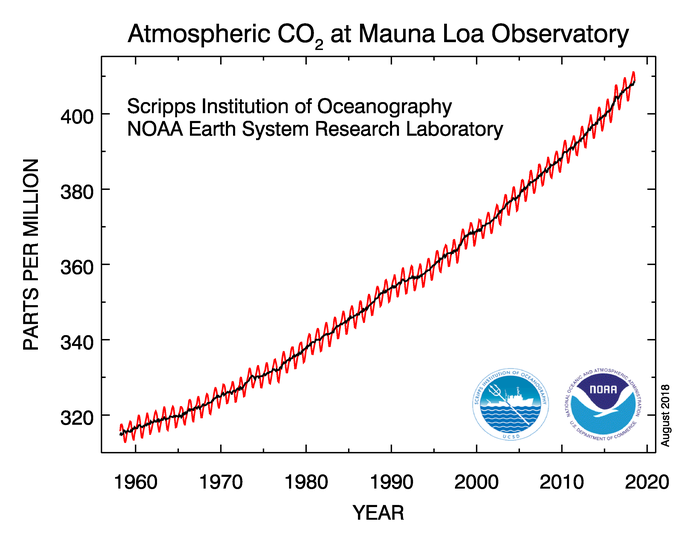

We have been directly measuring the atmospheric concentration of CO2 since 1958 in the Mauna Loa Observatory [28] in Hawaii, and have seen it increase steadily since then (see Figure 3.1 below). This is known as the Keeling curve and is named after Andrew Keeling, who initiated the measurements.

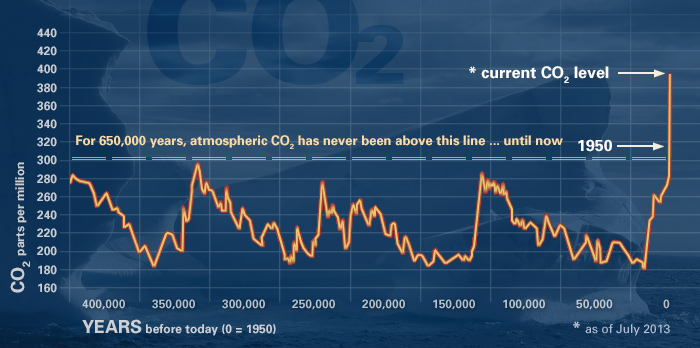

We also know with a very high level of certainty the concentration of the ancient atmosphere through time, as well through proxy measures such as ice core samples from ancient ice (click here for some links to explanations of how this is done [29] by clicking on the CO2 Past at the top of the page). The current levels of CO2 are almost certainly unprecedented in the past 800,000 years (credit: National Academy of Sciences) [30]. The chart below depicts the carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere for the past 400,000 years.

It is an established fact that the burning of fossil fuels releases carbon dioxide and that the concentration of carbon dioxide has been increasing rapidly since around the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the late 1700s. The Industrial Revolution is characterized by the increased use of fossil fuels - first coal, then oil, then natural gas. All of these non-renewable energy sources release CO2 when burned, and aside from minor natural occurrences like volcanic eruptions, are what has primarily caused the increased carbon dioxide concentration over the past 200+ years.

In short, energy is the primary culprit in anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. In fact, according to the International Energy Agency, two-thirds of global anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions are due to energy use and production (Credit: IEA, "Energy and Climate Change [32]," World Energy Outlook 2015). This boils down to the fact that we are emitting carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases at rates faster than can naturally be absorbed. This causes an imbalance, and thus the concentration increases.

Mythbusting: The Global Carbon Cycle

It is not unusual to hear something like the following as a reason to be skeptical of anthropogenic climate change: "The earth naturally emits WAY more CO2 than humans do. The emissions are so relatively small that they cannot have an impact on CO2 concentrations, never mind climate change."

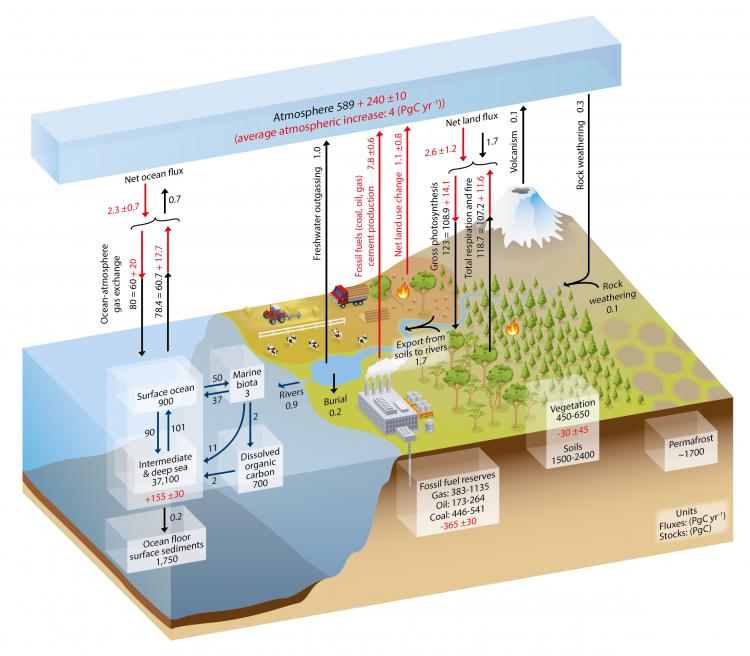

The earth does, in fact, emit significantly more CO2 than humans do! The image below is from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's (IPCC) most recent report, called the Fifth Assessment Report or simply AR5. This is an illustration of the global carbon cycle. Carbon, like most other elements, is constantly moving around the earth, e.g., being emitted and absorbed by oceans, being taken up by plants, being released by decaying plants, being released by volcanoes, etc. The carbon cycle illustrates this process. (Don't worry about analyzing this image if you don't want to - it's pretty dense, and you do not need to know any of the numbers.)

This is a pretty busy image, so I'll summarize it for you:

- Humans directly cause about 9 billion tonnes (Gt) of carbon to enter the atmosphere each year.

- Natural emissions are on the order of 170 Gt per year.

Hmm, okay, so there are way more natural than anthropogenic emissions. So why care so much about the measly 9 billion anthropogenic tonnes? As it turns out, if there were no anthropogenic emissions, the carbon cycle would likely even out, or perhaps even cause a reduction in carbon in the atmosphere. There are many natural processes that absorb carbon, mostly oceans, and vegetation. According to the IPCC, the total increase in carbon in the atmosphere is only about 4 Gt per year (including anthropogenic emissions). If you do a little math it becomes apparent: if that 9 Gt of emissions caused by humans were not there, then there would likely be no increase in overall concentration. Even though the relative contribution is small, anthropogenic emissions throw the global carbon cycle out of whack.

One good analogy of this process is weight gain. Let's say you average around 2,000 calories of food intake each day, and on average you burn off the same amount each day. If this continues over time, you will not gain weight. But if you add one extra 100 calorie snack each day, it will throw this balance out of whack. Even though you are only increasing your calorie intake by a measly 5%, over time this will cause weight gain. Well, it appears that the earth has put on some serious carbon weight in the past ~200 years, and it is almost entirely due to the extra human emissions!

Fact 3: The Climate Is Warming

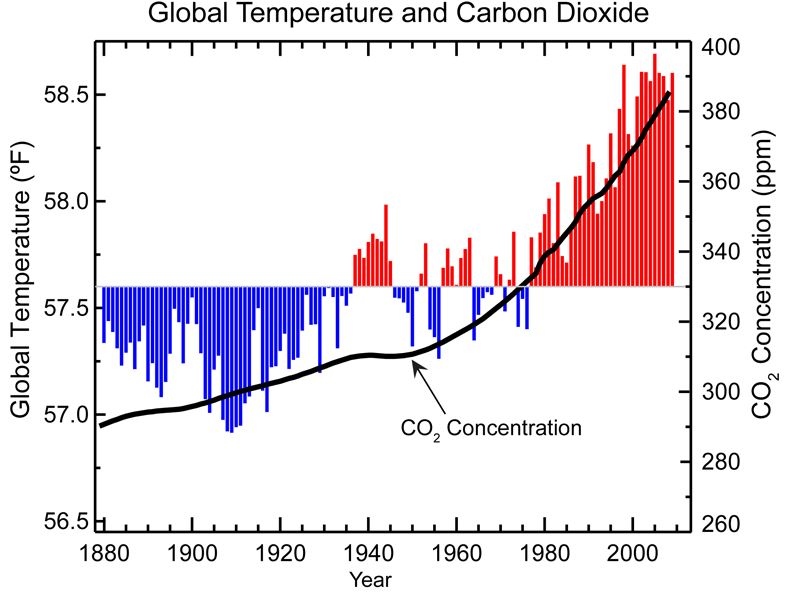

Humans have been taking direct temperature measurements since about 1880. There has been an upward trend in global temperature since around 1900, and the increase has become very sharp since about 1980.

Optional Reading

According to NASA [37]:

"Seventeen of the hottest 18 warmest years in the 136-year record all have occurred since 2001, with the exception of 1998. The year 2016 ranks as the warmest on record."

Based on this evidence (which has been corroborated by other scientific sources) and Figure 3.4 above, it is clear that the global temperature has been increasing since humans have been measuring it on a global scale, and it appears that the warming is accelerating.

One note of caution: The earth operates in cycles of thousands and millions of years, so less than 150 years of warming is not undeniable evidence that the climate will continue to warm. However, the correlation that is observed between increased CO2 levels and temperature, along with what we know about GHGs, is troubling.

Fact 4: If Climate Change Occurs as Many Scientists Believe, the Results Will Almost Certainly Be Catastrophic

There is wide consensus that if the climate continues to change and CO2 levels continue to rise the results will not be good (okay, "not good" is a pretty big understatement). As the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) stated in their 2007 report: "Taken as a whole, the range of published evidence indicates that the net damage costs of climate change are likely to be significant and to increase over time" (Credit: IPCC, quoted by NASA [38]). This is a stuffy way of saying that "things will probably be really bad and continue to get worse."

The link below outlines some of the possible impacts, some of which have already begun to occur. Note that I am not saying that all of these things will happen, even if climate change continues, but it is meant as a survey of some of the most commonly cited negative impacts of climate change. Also note that some of the likely consequences may be positive in some areas, including extended growing seasons in cool climate zones and some increased growth of plants due to extra carbon being available, but the overall impact will very likely be overwhelmingly negative.

Optional Reading

It is also very important to note that the most vulnerable to these impacts will be low-income and otherwise marginalized people all over the world. As the IPCC states in their 2014 assessment:

"(Climate change) risks are unevenly distributed and are generally greater for disadvantaged people and communities in countries at all levels of development" (IPCC, Climate Change 2014 Syntheses Report [40], p. 13).

Translation: the people with little power and/or resources will be disproportionately affected by climate change, regardless of whether they live in a low- or high-income country. This is thus an important social and environmental justice issue!

Fact 5: There is Broad Scientific Consensus that Humans are Most Likely the Primary Driver of Observed Climate Change

Multiple reports in peer-reviewed journals have found that at least 97% of scientists actively publishing in the climate field agree that the climate change observed in the past century is likely due to human influence, i.e., it is anthropogenic. See these links to some studies [41]. In 2015, 24 of Britain's top "Learned Societies" - groups of scientific experts, basically - wrote a letter [42] urging that we need to establish a "zero-carbon world" early in the second half of the 21st century. In the past 15 years, 18 U.S. scientific associations [41] have confirmed that climate change is likely being caused by humans. Big players in the private sector are concerned as well. For example, CEOs from 43 companies in various sectors (with over $1.2 trillion of revenue in 2014) signed an open lette [43]r urging action in April of 2015. Even Exxon Mobil states as their official position [44] on climate change (as of the summer of 2018) that:

"The risk of climate change is clear and the risk warrants action. Increasing carbon emissions in the atmosphere are having a warming effect. There is a broad scientific and policy consensus that action must be taken to further quantify and assess the risks."

Exxon Mobil, the world's largest publicly traded oil and gas company, is not known to be a friend of carbon reduction advocates. In fact, a study published in August of 2017 [45] found that they systematically misled the public for nearly 40 years about the dangers of climate change, even though they acknowledged the risks internally. Yet even they assert that emissions should be reduced.

Putting it All Together

Let's consider these facts together:

- We know that the greenhouse effect warms the planet and that carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas.

- We know that humans are emitting greenhouse gases at a rate that is increasing their concentration in the atmosphere.

- We know that the global climate is warming.

These three facts alone indicate that there is likely a problem. But, on top of this, you add that:

- The vast majority of active climate scientists agree that climate change is a problem and that climate change is at least very likely being caused by humans. So, the people that we trust to understand the climate widely agree that it is a problem.

- Finally, if climate change is happening, then the results will likely be devastating and on a global scale.

Even if we are not certain that humans are impacting the climate (we can never by 100% certain because we only have one planet to run this global "experiment" on), it is probably worth taking the precaution to prevent it if it is true. Yes, it is possible that so many climate experts are wrong - it is a rare occurrence that so many experts are wrong, but there is a possibility, however slim. And yes, we do not know for a fact that humans impact the climate, though basically all signs point to it being the case. And yes, there will be costs associated with making the change to a low-carbon society. But why do people buy life insurance? What about fire insurance? As silly as it sounds, what about buying an extended warranty on a new piece of electronics, or extra insurance for a rental car? The point is that even though the likelihood of using those insurances is minimal - probably less than the likelihood that climate change is caused by humans - people are willing to pay the cost in order to avoid catastrophe. The same could be said of climate change. Taking steps to avoid the worst-case scenario, or perhaps something near the worst-case scenario, is known as the precautionary principle. This may cost money or other resources in the short term, but is seen as worth it because of the situation it may prevent.

One quick addendum to this: If steps are successfully taken to reduce climate emissions to a sustainable level, it is very likely that there will also be cleaner air, less environmental damage, more energy security (not being dependent on another country for energy), and probably more active/healthy citizens. Something to think about.

Further Reading - OPTIONAL

If you are interested in reading more about this topic, here are some suggested readings.

- "Climate Change Evidence & Causes: An overview from the Royal Society and the US National Academy of Sciences [30]." The Royal Society and the National Academy of Sciences.

- "Climate Change 2014 Synthesis Report: Summary for Policymakers [40]." Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- Link to a number of IPCC documents [46].

- "Energy & Climate Change [32]." World Energy Outlook Special Report. International Energy Agency, 2015.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's Climate Change Website [47]

Optional (But Strongly Suggested)

Now that you have completed the content, I suggest going through the Learning Objectives Self-Check list at the top of the page.

Water

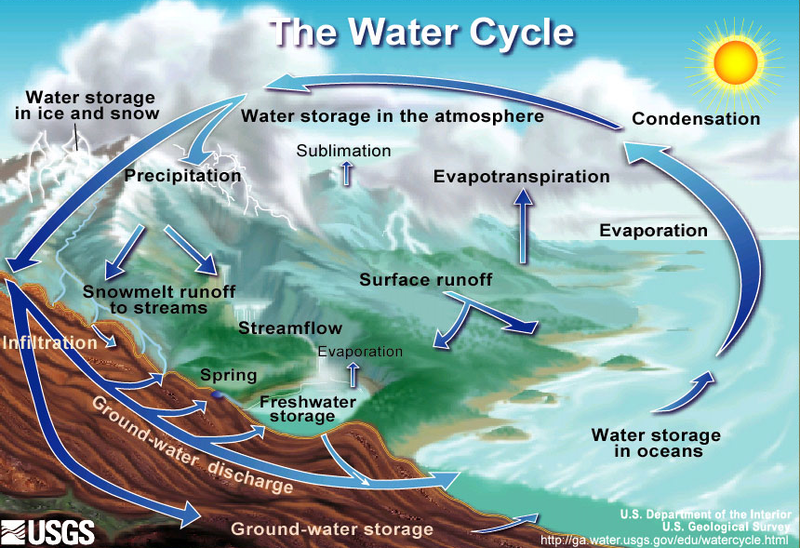

I'm sure I don't need to tell you that water is essential for life, including humans. The earth is considered a "Goldilocks" planet (not too hot, not too cold) based on the fact that water can exist in a liquid state over much of the planet. All water on earth cycles in and out of this system at different time scales (see the figure above), and has been for millennia. In fact, the water that you used to brush your teeth this morning may have been part of the iceberg that sank the Titanic, ran through ancient Roman aqueducts, or was used to wash the makeup off of Cleopatra's face. This is important to understand, because the water we have now is all of the water we'll ever have. There is no shortage of water, but freshwater is limited. The earth naturally replenishes fresh, clean water, but at a limited rate, and there are many obvious indicators that humans are not using freshwater at a sustainable rate.

The following are a number of facts presented by the World Health Organization in their article "Drinking Water [51]." You are welcome to read through the article, but that is not necessary.

- In 2015, 71% of the global population (5.2 billion people) used a safely managed drinking-water service – that is, one located on premises, available when needed, and free from contamination.

- 89% of the global population (6.5 billion people) used at least a basic service. A basic service is an improved drinking-water source within a round trip of 30 minutes to collect water.

- 844 million people lack even a basic drinking-water service, including 159 million people who are dependent on surface water.

- Globally, at least 2 billion people use a drinking water source contaminated with faeces.

- Contaminated water can transmit diseases such diarrhoea, cholera, dysentery, typhoid, and polio. Contaminated drinking water is estimated to cause 502 000 diarrhoeal deaths each year.

- By 2025, half of the world’s population will be living in water-stressed areas.

- In low- and middle-income countries, 38% of health care facilities lack an improved water source, 19% do not have improved sanitation, and 35% lack water and soap for handwashing...

- Contaminated water and poor sanitation are linked to transmission of diseases such as cholera, diarrhoea, dysentery, hepatitis A, typhoid, and polio. Absent, inadequate, or inappropriately managed water and sanitation services expose individuals to preventable health risks...

- Some 842 000 people are estimated to die each year from diarrhoea as a result of unsafe drinking-water, sanitation, and hand hygiene. Yet diarrhoea is largely preventable, and the deaths of 361 000 children aged under 5 years could be avoided each year if these risk factors were addressed...

- Diarrhoea is the most widely known disease linked to contaminated food and water but there are other hazards. Almost 240 million people are affected by schistosomiasis – an acute and chronic disease caused by parasitic worms contracted through exposure to infested water...

- Climate change, increasing water scarcity, population growth, demographic changes and urbanization already pose challenges for water supply systems. By 2025, half of the world’s population will be living in water-stressed areas.

The news is not all bad, though - according to the World Economic Forum [52] (WEF) the United Nations' Millennium Development Goal of "halv(ing) the proportion of the world's population without sustainable access to safe water" was met in 2010. However, the article indicates that while the broad goal was met (global percentage), none of the 48 "least developed" countries met the goal. As usual, there is a deficiency in terms of equity with regards to access to clean water, with "low-income, informal or illegal" populations "usually having less access to improved sources of drinking water than other residents."

These and other factors combine to make access to water an essential part of the quality of life. The United Nations has declared access to water and sanitation a human right and thus should be provided to all people equitably. The UN realizes that access is a fundamental component of the ability to live one's life and further that "clean drinking water and sanitation are essential to the realization of all human rights" (Credit: United Nations [53]).

Water Scarcity

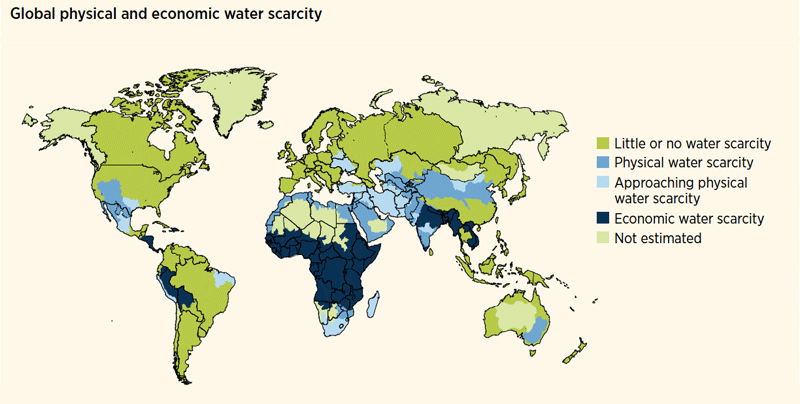

- Physical water scarcity "occurs when the demand for water...is higher than the available resource." This is pretty straightforward: this occurs when an area needs more water than it has. This usually occurs in dry areas of the world, including wealthier ones like the southwestern U.S.

- Economic water scarcity "occurs when human, institutional and financial capital limit access to water even though water in nature is available for human needs." In other words, the water is there and is accessible, but the people are not capable of getting to it. This tends to happen in lower income countries of the world, and areas with social and/or political instability.

Credit: FAO [54]

Optional Viewing

The following video from FAO has no audio narration, so there is nothing wrong with your speakers/headphones! Note that the data provided are a few years old, but have not changed much. It is important to point out that despite what is indicated in the video above, reducing domestic water use is not the most effective way to reduce total water use. As you will see in the video below, much more water is used as a result of farming and industrial uses worldwide.It says: Water scarcity occurs when the demand for water from all sectors (agriculture, cities, environment, etc...) is higher than the available resource. Because water has been relatively abundant throughout our existence on earth, we have come to take it for granted. However, we now find our water supplies severely reduced as water scarcity is fast becoming one of the most serious resource issues we face today. The amount of water on our planet is fixed, but very little of it is available for us to use with about 2.5 percent of all water on earth being freshwater and 68.9 percent of the freshwater is locked in glaciers, 30.8 percent in groundwater, and 0.3 percent in lakes and rivers.

Currently, one-third of the world population lives in countries where there isn't enough water or its quality has been compromised. By 2025 this number is expected to rise to two-thirds.

There are two types of water scarcity. One is known as Physical Water Scarcity. This occurs when there is not enough water to meet our needs. Arid regions are generally associated with physical water scarcity. Physical water scarcity occurs in: the western United States, northern Africa, Saudi Arabia, eastern Australia, and areas of India and northern China. More areas are rapidly approaching physical water scarcity. Africa, Asia and the Pacific, and the Near East use over 75 percent of their water for agriculture. The other type of water scarcity is known as Economic Water Scarcity. This occurs when human, institutional and financial capital limit access to water even though water in nature is available for human needs. Economic water scarcity occurs in central and northern South America, Middle Africa, and in and around India. Poor households in developing countries spend higher portions of their income on water than families in industrialized nations.

You may think water issues are somebody else's problem. But in a few years, it will be yours too. Follow a few easy steps to do your part in maintaining this precious resource. Don't throw your cooking water down the drain. Close the tap when brushing your teeth. Don't buy unnecessary goods, as everything produced uses water.

Here are some things to keep in mind about water scarcity, according to the United Nations [55]:

Water scarcity already affects every continent. Around 1.2 billion people, or almost one-fifth of the world's population, live in areas of physical scarcity, and 500 million people are approaching this situation. Another 1.6 billion people, or almost one quarter of the world's population, face economic water shortage (where countries lack the necessary infrastructure to take water from rivers and aquifers).

Water scarcity is among the main problems to be faced by many societies and the World in the XXIst century. Water use has been growing at more than twice the rate of population increase in the last century, and, although there is no global water scarcity as such, an increasing number of regions are chronically short of water.

Water scarcity is both a natural and a human-made phenomenon. There is enough freshwater on the planet for seven billion people but it is distributed unevenly and too much of it is wasted, polluted and unsustainably managed...

- Around 700 million people in 43 countries suffer today from water scarcity.

- By 2025, 1.8 billion people will be living in countries or regions with absolute water scarcity, and two-thirds of the world's population could be living under water stressed conditions.

- With the existing climate change scenario, almost half the world's population will be living in areas of high water stress by 2030, including between 75 million and 250 million people in Africa. In addition, water scarcity in some arid and semi-arid places will displace between 24 million and 700 million people.

- Sub-Saharan Africa has the largest number of water-stressed countries of any region

- Economic water scarcity: Sub-Saharan Africa, parts of northwestern South America, northern India and some of southeast Asia

- Physical water scarcity: Northern China, parts of the Middle East, southeastern Australia, southwest U.S.

- Approaching physical water scarcity: Central Mexico and parts of Texas, South Africa, most of the Middle East, some in northern China.

- Little or no water scarcity: Most of the rest of the world, except for Alaska, Greenland, Siberian Russia, and Central Australia, which had no data.

Considering that about 97% of the water in the world is salt water, one of the ways that scarcity can be overcome is through desalination. This is being done all over the world, but current desalination technology requires an immense amount of energy [56], can impact local environments in a variety of ways [57], and is quite expensive [56]. Desalination is probably necessary to satisfy the world's energy needs (and likely increasingly so), particularly in arid areas of the world. But as succinctly stated by Scientific American [57]: "Due to its high cost, energy intensiveness and overall ecological footprint, most environmental advocates view desalinization...as a last resort for providing fresh water to needy populations."

Water Use

It is a common misconception that household water use (taking showers, washing dishes, etc.) is the primary driver of water use in the world, but only about 8% of global freshwater consumption is from domestic uses. Most - about 70% - is used for agriculture, and over 20% is used for industrial purposes (e.g., manufacturing, energy generation).

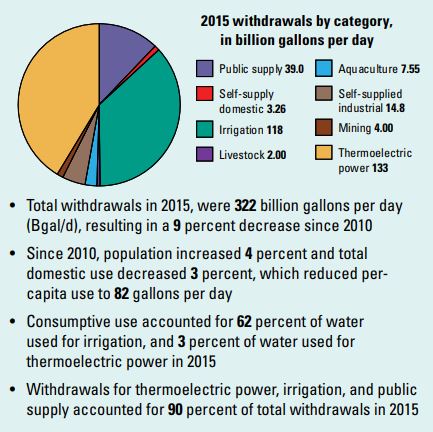

It turns out that U.S. water consumption follows a similar pattern. The chart below shows the percent of consumption different sectors of use are responsible for. Some interesting things to note:

- Thermoelectric cooling is the single biggest user of total water in the U.S. (about 40%). (Keep in mind that about 50 billion gallons of salt water are used for thermoelectric power, so irrigation is the biggest single freshwater user in the U.S.).

- Irrigation is responsible for about 38% of annual water use, but about 42% of freshwater used.

- Domestic water use accounts for about 2% of the total.

| Public Supply | 39,000 |

|---|---|

| Self-Supplied Domestic | 3,260 |

| Irrigation | 118,000 |

| Livestock | 2,000 |

| Aquaculture | 7,550 |

| Self-supplied Industrial | 14,800 |

| Mining | 4,000 |

| Thermoelectric Power | 133,000 |

Note: Values do not sum to 322,000 Mgal/d because of independent rounding.

- Total withdrawals were 322,000 million gallons per day (355 billion gallons per day).

- Thermoelectric power, irrigation, and public supply account for 90 percent of total withdrawals.

- Withdrawals declined since 2010 in all categories except irrigation.

- Freshwater withdrawals were about 88% of the total.

- Surface water supplied 78 % of all withdrawals

Keep in mind that not all water use is consumptive. For example, almost all water used in thermoelectric cooling is used for just that - cooling. Most of it ends up either as steam or as warm(er) water downstream of the power plant. Most of the water used for irrigation is consumptive (62%, according to the USGS), in that it ends up being incorporated into the crops. When water moves from one part of the water cycle to another, it can be days (water lasts about 9 days on average in the atmosphere) to thousands of years (e.g., in the ocean) before it moves to another part of the cycle. (Refer to this description of residence time [59] from the National Center for Environmental Research.)

Water Footprint

Given that most water in the world is used to grow crops and generate electricity, it follows that most of the water we use is used indirectly. Every time you use something that must be grown as a crop (food, cotton, wood, etc.) or use electricity (assuming it is from a power plant), you contribute to water use. This "hidden" water of everyday products and processes is considered the water footprint. The Water Footprint Network [60] defines water footprint as "the amount of water used to produce each of the goods and services we use" (Credit: Water Footprint Network [61]).

A water footprint - like an ecological footprint - can be calculated for individual products, individual people, or groups of people (communities, cities, countries, etc.). The folks at the Water Footprint Network provide a lot of information about water footprints [62]. Feel free to take a look at the Water Footprint Network's product gallery [63]to see the (often surprising) water footprint of many common items.

Summary and Final Tasks

Summary

By now you should be able to:

- analyze the credibility of information sources;

- identify characteristics of the Anthropocene;

- explain how the greenhouse effect increases the average surface temperature of the earth;

- identify evidence for anthropogenic climate change;

- identify characteristics of the 6th Mass Extinction;

- explain the benefits of biodiversity;

- analyze the sustainability impacts of freshwater availability; and

- apply the precautionary principle to sustainability considerations.

Reminder - Complete all of the Lesson 3 tasks!

You have reached the end of Lesson 3! Double-check the to-do list on the Lesson 3 Overview page [64] to make sure you have completed all of the activities listed there before you begin Lesson 4.