Lessons

This is the course outline.

Lesson 1: Introduction to Petroleum Refining and Crude Oil Composition

Lesson 1 Overview

Lesson 1 Overview

Video: FSC 432 Lesson 1 (2:04)

Overview

Petroleum provides the largest fraction of primary energy supply in the U.S. and in the world [Figure 1.1,eia1]. Resource consumption patterns shown in Figure 1.1 reflect major epochs in human history, such as The Industrial Revolution, ushering in the rapid increase in coal consumption. Petroleum trace, for example, marks the mass production of automobiles with the introduction of Model T by Ford, world wars, supply crises of 1973 and 1979 and the economic recession in 2008. Transportation of people and goods in many parts of the world depends almost completely on petroleum fuels, such as gasoline, jet fuel, diesel fuel, and marine fuel. Apart from the fuels, materials that are necessary for operating the combustion engines of cars, trucks, planes, and trains also come from petroleum. These materials include lubricating oils (motor oils), greases, tires on the wheels of the vehicles, and asphalt to pave the roads for smooth rides in transportation vehicles. All petroleum fuels and many materials are produced by the processing of crude oil in petroleum refineries. Petroleum refineries also supply feedstock to the petrochemicals and chemical industry for producing all consumer goods from rubber and plastics (polymers) to cosmetics and medicine. Only ten percent of petroleum consumption, the portion that is not used for transportation or other energy outlets, is sufficient to manufacture all the materials used in human economy, with the exception of those derived from wood or minerals.

The petroleum industry consists of two separate operations: Upstream and Downstream Operations. Upstream operations involve exploration of new oil reserves, development of oil fields, constructing the well-head and crude oil production facilities. Downstream operations cover processing of crude oil in petroleum refineries to produce liquid and gaseous fuels and materials for the market. This course addresses petroleum refining to review how a variety of physical processes and chemical reactions in separate refinery units are integrated to process compliant fuels and materials.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you will be able to:

- recognize the significance of petroleum fuels in the U.S. energy supply;

- express the overall objectives of petroleum refining;

- identify the economic and environmental drivers of petroleum refining;

- describe the overall approach to petroleum refining and categorize refinery processes and products;

- portray chemical constitution of petroleum.

What is due for Lesson 1?

This lesson will take us one week to complete. Please refer to the Course Syllabus for specific time frames and due dates. Specific directions for the assignments below can be found on the Assignment page within this lesson.

| Readings | J. H. Gary, G. E. Handwerk, Mark J. Kaiser, Chapter 1, pp. 1-12; Chapter 3, pp. 62-65 |

|---|---|

| Assignments | For your information, review the most recent supply of petroleum fuels from the data given at U.S. Energy Information Administration [3] (eia.gov) and research how petroleum refining addresses the environmental concerns from the combustion of petroleum fuels in internal combustion engines. |

Questions?

If you have any questions, please post them to our Help Discussion (not email), located in Canvas. I will check that discussion forum daily to respond. While you are there, feel free to post your own responses if you, too, are able to help out a classmate.

Market Drivers for the Refining Industry

Market Drivers for the Refining Industry

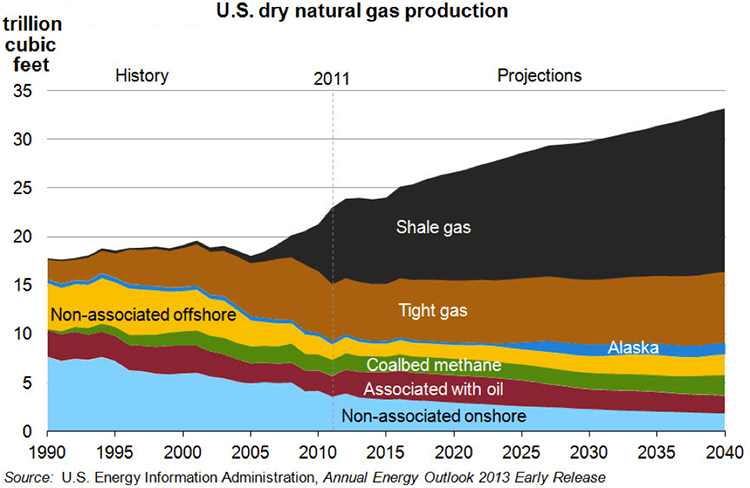

Markets and demand for refinery products depend on the dynamics of a global economy. It is generally agreed that oil and gas will continue to be the primary energy resource in the U.S. and world economies for decades to come. Because of the projected increase in the production of oil in tight formations, the United States is expected to become an exporter of petroleum products and crude oil after decades of being an importer (Figure 1.2, EIA Annual 2013, eia.gov). Petroleum fuels will continue to dominate the transportation sector, but the following trends should be noted:

- increasing fuel economy of vehicles (offset by increasing number of vehicles and miles driven);

- more strict environmental regulations with demand for cleaner fuels;

- biofuels as additives (e.g., ethanol, biodiesel) or alternative fuels in niche markets (jet fuel from algae);

- demand for high-quality, high-performance fuels

Competitive forces in the global economy lead to joint ventures and mergers and shutting down of inefficient refineries, or shutting down of processing units with low efficiency within refineries. Figure 1.3 shows the changes in the refinery capacity and number of refineries in the U.S. since 2000. The increasing refining capacity, with the decreasing number of refineries, results in the closing down of small inefficient refineries while expanding the large refineries.

Regarding the global competition, the technological advancement addresses the degrading quality of crude oils to produce cleaner and higher quality petroleum fuels. On the supply side, there is the increasing abundance of natural gas liquids (ethane, propane, n-butane, and isobutane) due to increased shale gas production in the U.S. and elsewhere. These liquids enter refineries as new feedstock in addition to crude oil supply.

Refineries need process improvements to advance their capabilities to deal with the changing crude oil base and changing environmental regulations. These improvements in refinery processes would need to create and use, for example:

- new catalysts and new chemistry;

- more sophisticated process modeling and computational methods;

- more effective use of computers in refinery management;

- online monitoring and property measurements;

- new materials to reduce maintenance and extend the useful life of the equipment.

Concerns for efficiency include running a refinery efficiently and producing fuels that will burn efficiently in the combustion engines, as follows:

- Efficiency of refinery processes

- Minimize waste and optimize the yield and properties of the refinery products to obtain maximum value from the crude oil.

- Increase the energy efficiency of each unit in the refinery.

- Fuel economy in internal combustion engines

- Produce high-performance fuels for efficient operation of combustion engines.

An Overview of Refinery Products and Processes

An Overview of Refinery Products and Processes

Considering the market drivers just reviewed along the small profit margins that are often usually associated with petroleum refinery products, refineries should carefully select the crude oil feedstock and configure the refinery processes such that they produce the desirable petroleum products at the lowest cost.

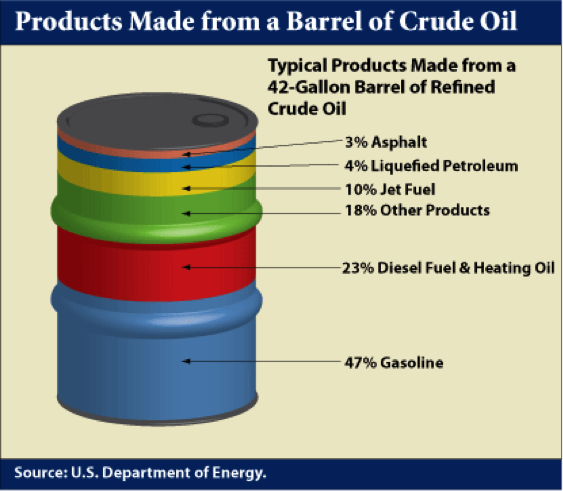

In the U.S. refineries, a principal focus is on the production of gasoline because of high demand. Diesel fuel is the principal refinery product in most other parts of the world. Figure 1.4 shows a typical distribution of products from a barrel of crude oil in a U.S. refinery. Distillation process separates the crude oil into boiling point fractions. The liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) constitutes the lowest boiling point (most volatile) product from a refinery and higher boiling fractions lead to most desirable distillate liquids, such as gasoline, jet fuel, diesel fuel, and fuel oil in the increasing order of boiling points, while asphalt is made from the residual fraction remaining after distillation.

The following animation shows a refinery flow chart indicating some of the major refinery processes and refinery products. Note that the distillation process (Fractionation Tower) separates crude oil into a number of distillate fractions that are sent as feedstocks to different processes, some of which are interconnected. It is also important to recognize that petroleum refining not only produces transportation fuels and fuels for space heating or industrial furnaces, but also produces materials needed for the operation of the combustion engines and paving the roads for vehicles to travel on.

Video: FSC 432 Refinery Flow Chart (4:12)

Figure 1.5 indicates that chemical constitution and physical properties of crude oils are important parameters that guide the refinery configurations. The refining processes can be divided into four groups, as indicated. While the separation processes involve just physical phenomena, the conversion, finishing, and support processes require chemical changes, i.e., breaking chemical bonds to modify the molecular structure of the feedstocks. These changes are necessary to produce the fuels and materials in accordance with industrial/commercial specifications.

Figure 1.6 (progressive image, 25 seconds) shows a more detailed refinery block diagram to show how different processes are integrated for producing the desired fuels and materials.

Separation processes, such as distillation, dewaxing, and deasphalting make use of the differences in the physical properties of crude oil components to separate groups of hydrocarbon compounds or inorganic impurities, whereas conversion processes cause chemical changes in the hydrocarbon composition of crude oils. For example, Fluid Catalytic Cracking process breaks chemical bonds in long-chain alkanes to produce shorter chain alkanes to produce gasoline from higher boiling gas oil fractions. Finishing processes involve hydrotreating to remove heteroatoms (S, N, and metals) and product blending to produce fuels and materials with desired specifications and in compliance with environmental and government regulations. Finally, supporting processes provide the recovery of the removed heteroatoms or heteroatom compounds, production of the hydrogen necessary for conversion and hydrotreating processes, and effluent water treatment systems.

Knowledge Check

Why is diesel fuel preferred over gasoline in many countries in the world?

Chemical Constitution of Crude Oil

Chemical Constitution of Crude Oil

Crude oil contains organic compounds, heteroatom compounds (S,N,O), hydrocarbons (C, H), metals and organic (Ni, V, Fe) and inorganic (Na+, Ca++, Cl-) compounds as listed in Figure 1.7. Compounds that contain only elements of carbon and hydrogen are called hydrocarbons and constitute the largest group of organic compounds found in petroleum. There might be as many as several thousand different hydrocarbon compounds in crude oil. Hydrocarbon compounds have a general formula of CxHy, where x and y are integer numbers.

Hydrocarbons are generally divided into four groups: (1) paraffins, (2) olefins, (3) naphthenes, and (4) aromatics (Figure 1.8). Among these groups, paraffins, olefins, and naphthenes are sometimes called aliphatic compounds, as different from aromatic compounds. The lightest hydrocarbon found as a dissolved gas is methane (CH4), the main component of natural gas. Olefins are not usually found in crude oils, but produced in a number of refining processes.

Aromatic Hydrocarbons

Aromatic Hydrocarbons

Aromatic hydrocarbons are an important series of hydrocarbons found in almost every petroleum mixture from any part of the world. Aromatics are cyclic but unsaturated hydrocarbons with alternating double bonds (Figure 1.12). The simplest aromatic hydrocarbon is benzene (C6H6). The name “aromatic” refers to the fact that such hydrocarbons are commonly fragrant compounds. Although benzene has three carbon-carbon double bonds, it has a unique arrangement of electrons with resonance structures of the double bonds (aromaticity) that allow benzene to be relatively stable. However, benzene is known to be a cancer-inducing compound. For this reason, the amount of benzene allowed in petroleum products such as gasoline or fuel oil is limited by government regulations in many countries. Under standard conditions, benzene, toluene, and xylene are in liquid form whereas higher aromatics such as naphthalene occur as solids in isolation, but dissolve to form a liquid solution with simple aromatics.

Knowledge Check

What constitutes the white crystals of moth balls?

Polyaromatic and Hydroaromatic Compounds

Polyaromatic and Hydroaromatic Compounds

Some of the common aromatics found in crude oil and petroleum products are benzene derivatives with attached methyl, ethyl, propyl, or higher alkyl groups. This series of aromatics is called alkylbenzenes, and compounds in this homologous group of hydrocarbons have the general formula of CnH2n-6 (where n ≥ 6). Generally, an aromatic series with only one benzene ring is also called mono- aromatics or mononuclear aromatics. However, heavy petroleum fractions and residues contain unsaturated multirings with many benzene and naphthene rings attached to each other. Such aromatics that exist as solids in isolation are also called polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) or polynuclear aromatics (PNAs) (Figure 1.13). Heavy crude oils usually contain more aromatics than light crudes. It is common to have compounds with naphthenic and aromatic rings side by side (hydroaromatics, or naphthenoaromatics, Figure 1.13) especially in heavy fractions.

Figure 1.13 shows examples of PAHs, such as anthracene, phenathrene, and pyrene. The configuration of rings in PAHs strongly influences the physical and chemical properties of these compounds. For example, three-ring aromatics anthracene and phenanthrene have significantly different properties. In petroleum, PAHs exist mostly as alkyl substituted ring systems such that the substitutent alkyl groups (e.g., methyl, ethyl) replace (substitute for) the hydrogen atoms on the rings.

Normally, high-molecular-weight polyaromatics contain several heteroatoms such as sulfur, nitrogen, or oxygen, but these compounds are still called aromatic compounds because their electronic configurations maintain the aromatic character.

Sulfur is the most important heteroatom found in crude oil and refinery products petroleum, and it can be found in cyclic (e.g., thiophenes) and noncyclic compounds such as mercaptans (R-S-H) and sulfides (R-S- R′), where R and R′ are alkyl groups. Sulfur in natural gas is usually found in the form of hydrogen sulfide (H2S). Figure 1.14 shows the types of sulfur compounds in crude oils. The amount of sulfur in a crude oil may vary from 0.05 to 6 % by weight. The presence of sulfur in finished petroleum products is not desirable. For example, the presence of sulfur in gasoline can promote corrosion of engine parts and produce sulfur oxides upon combustion, contributing to air pollution.

Normally, the concentration of the other heteroatom compounds (nitrogen, oxygen, and metals) in crude oils is usually lower than that of the sulfur compounds. Figure 1.15 shows the nitrogen compounds that may be found in crude oils.

Generally, in heavier crude oils the proportions of carbon, sulfur, nitrogen, and oxygen compounds are higher at the expense of hydrogen content. Heavier crude oils also contain organometallic compounds of common nickel and vanadium (Figure 1.16). These compounds are highly corrosive and toxic and should be removed in the refinery. Nickel, vanadium, and copper can also severely affect the activities of catalysts and result in lower quality products. Organometallic compounds tend to concentrate in heavy, or residual fractions of crude oils.

Knowledge Check

What is the principal type of air pollution caused by the emission of sulfur oxides into the atmosphere?

Paraffins

Paraffins

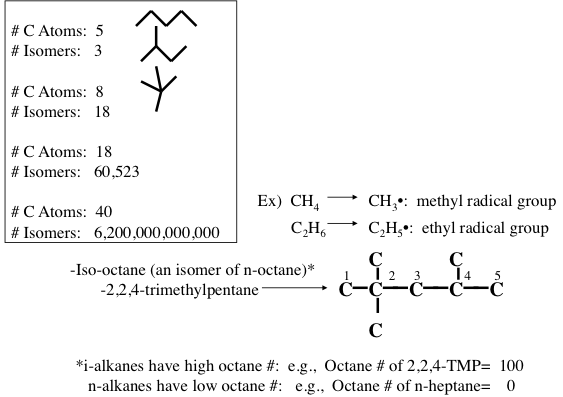

Paraffins are also called alkanes and have the general formula of CnH2n+2, where n is the number of carbon atoms in a given molecule. Paraffins are divided into two groups of normal and isoparaffins. Normal paraffins or normal alkanes are simply written as n-paraffins or n-alkanes, and they are open, straight-chain saturated hydrocarbons. The second group of paraffins is called isoparaffins, which are branched-type hydrocarbons, and they begin with isobutane (also called methylpropane), which has the same closed formula as n-butane (C4H10). Compounds of different structures with the same closed formula are called isomers (Figure 1.9). For example, the open formula for n-butane, n-C4, can be shown as CH3-CH2-CH2-CH3, based on the quadrivalency of the carbon atom, and for simplicity, only the carbon-carbon bonds are drawn and most C-H bonds are omitted, as shown in Figure 1.7 and 1.8 on the previous page. Paraffins are the largest series of hydrocarbons found in petroleum and beginning with the simplest compound, methane.

Under standard conditions of temperature and pressure (STP), the first four members of the alkane series (methane, ethane, propane, and butane) are in gaseous form, and compounds starting from C5H12 (pentane) to n-heptadecane (C17H36) are liquids (constituting large fractions of hydrocarbons found in liquid fuels (e.g., gasoline, jet fuel, and diesel fuel), whereas n-octadecane (C18H38) or heavier compounds exist in isolation as wax-like solids at STP. These heavier paraffins are soluble in lighter paraffins or other hydrocarbons and can be found in diesel fuel and fuel oils. Paraffins from C1 to C40 usually appear in crude oil (heavier alkanes in liquid solution, not as solid particles) and represent up to 20% of crude by volume.

Figure 1.10 shows the statistically possible number of isomers of paraffins that increase exponentially with carbon number, starting with just one isomer for butane, reaching approximately 60,000 for C18 paraffins. Note that the branching in hydrocarbons causes significant changes in physical properties (e.g., boiling point and density, Figure 1.11) and chemical behavior (e.g., octane number, Figure 1.10) of paraffins with the same carbon number. Note in Figure 1.10 that the removal of an H atom from alkanes generates free radicals (reactive species containing unpaired electrons) that are called alkyl species (e.g., methyl formed from methane and ethyl formed from ethane by removing a hydrogen atom) also a radical with an unpaired electron. Also note the nomenclature using alkyl groups to specifically name isoalkanes (e.g., 2,2,4-trimethylpentane to designate a specific iso-octane).

Naphthenes or cycloalkanes are rings or cyclic saturated hydrocarbons with a general formula of CnH2n5H10), cyclohexane (C6H12), and their derivatives such as n-alkylcyclopentanes are normally found in crude oils.

Assignments

Assignment Reminder

Each week, you will be required to do assignments. The assignment for this week is:

For your information (no submission), review the most recent supply of petroleum fuels from the data given at U.S. Energy Information Administration [4] and research how petroleum refining addresses the environmental concerns from the combustion of petroleum fuels in internal combustion engines.

Self-Check Questions

Self-Check Questions

Take a few minutes to answer the five questions below. Use the arrow to go to the next question. When you are ready, click Check to see the solution.

Summary and Final Tasks

Summary

Petroleum, the most important crude oil, consists of a mixture of hydrocarbon compounds including paraffinic, naphthenic, and aromatic hydrocarbons with small amounts of impurities including sulfur, nitrogen, oxygen, and metals. The first process in petroleum refining operations is the separation of crude oil into its major constituents, using distillation to separate the crude oil constituents into common boiling-point fractions. Other separation processes include deasphalting to remove the heaviest fraction of crude oil, asphalt, and dewaxing to remove long-chain n-paraffins called wax.

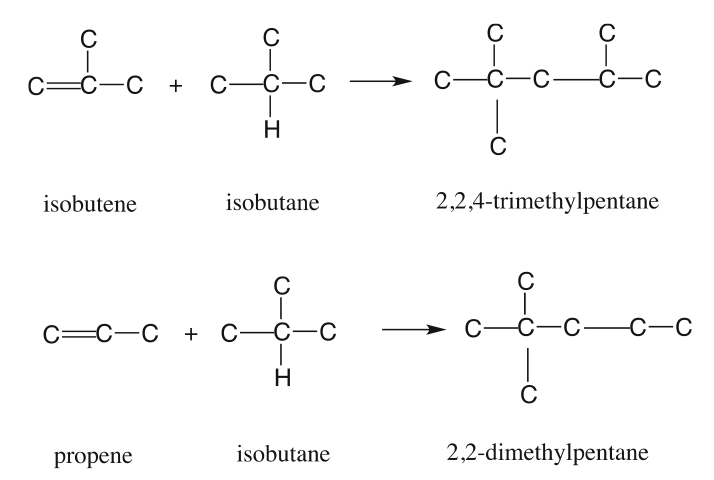

To meet the demands for high-octane gasoline, jet fuel, and diesel fuel, heavier components of crude oils are converted to gasolines and other distillate fuels. Among the conversion processes are cracking, coking, and visbreaking that are used to break large petroleum molecules into smaller ones. Polymerization and alkylation processes are used to combine molecules smaller than those in gasoline into larger ones to make more gasoline in the refinery. Isomerization and reforming processes are applied to rearrange and reform the structure of hydrocarbons to produce higher-value gasoline components of a similar molecular size.

Finishing processes in a refinery processes stabilize and upgrade petroleum products by hydrogenation and remove undesirable elements, such as sulfur and nitrogen, by hydrotreating processes. Blending of many product streams, to come up with commercial refinery products with the required specifications, also belong to the category of finishing processes.

Lesson Objectives

You should now be able to:

- recognize the significance of petroleum fuels in the U.S. energy supply;

- express the overall objectives of petroleum refining;

- identify the economic and environmental drivers of petroleum refining;

- describe the overall approach to petroleum refining and categorize refinery processes and products;

- portray chemical constitution of petroleum.

Reminder - Complete all of the Lesson 1 tasks!

You have reached the end of Lesson 1! Double-check the to-do list below to make sure you have completed all of the activities listed there before you begin Lesson 2. Please refer to the Course Syllabus for specific time frames and due dates. Specific directions for the assignment below can be found within this lesson.

| Readings | J. H. Gary, G. E. Handwerk, Mark J. Kaiser, Chapter 1, pp. 1-12; Chapter 3, pp. 62-65 |

|---|---|

| Assignments | For your information, review the most recent supply of petroleum fuels from the data given at The U.S. Energy Information Administration website [3] (eia.gov) and research how petroleum refining addresses the environmental concerns from combustion of petroleum fuels in internal combustion engines. |

Questions?

If you have any questions, please post them to our Help Discussion (not email), located in Canvas. I will check that discussion forum daily to respond. While you are there, feel free to post your own responses if you, too, are able to help out a classmate.

Lesson 2: Properties and Classification of Crude Oil

Lesson 2 Overview

Lesson 2 Overview

Video: FSC 432 Lesson 2 (2:27)

Overview

Physical properties and composition of crude oil provide critical information for the optimum operation of a petroleum refinery. This information does not only help predict the physical behavior of crude oil in refinery units, but also gives insight into its chemical composition. Therefore, the physical properties can be related to chemical properties of crude oil and its fractions and the characteristics of the resulting refinery products. The most important properties of crude include density, viscosity, boiling point distribution, pour point, and the concentration of various contaminants.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- define the significant properties of crude oil, including density, viscosity, average boiling point, sulfur, and salt content;

- understand the significance of crude oil properties in terms of refinery objectives, and describe crude oil assay;

- define and interpret the classification factors (Watson, UOP, VGC, and BMCI) as they relate to the hydrocarbon composition of crude oils;

- calculate average boiling points for crude oils using different averaging techniques and differentiate Watson and UOP characterization factors;

- analyze the elemental composition of crude oils and outline ternary classification of crude oils with respect to hydrocarbon composition, i.e., aromatics, paraffins, and naphthenes;

- assess the use of ternary classification of crude oils to estimate the refinery product yields.

What is due for Lesson 2?

This lesson will take us one week to complete. Please refer to the Course Syllabus for specific time frames and due dates. Specific directions for the assignments below can be found on the Assignments page within the Lesson.

| Readings | J. H. Gary, G. E. Handwerk, Mark J. Kaiser, Chapter 3, pp. 57-61, 65-70 and the course material from this site |

|---|---|

| Assignments | Exercise 1 - Submit to the Exercise 1 Assignment in the Lesson 2 Module.

|

Questions?

If you have any questions, please post them to our Help Discussion (not email), located in Canvas. I will check that discussion forum daily to respond. While you are there, feel free to post your own responses if you, too, are able to help out a classmate.

API Gravity

API Gravity

Density is defined as mass per unit volume of a fluid. The density of crude oil and liquid hydrocarbons is usually reported in terms of specific gravity (SG) or relative density, defined as the density of the liquid material at 60°F (15.6°C) divided by the density of liquid water at 60°F. At a reference temperature of 15.6°C, the density of liquid water is 0.999 g/cm3 (999 kg/m3), which is equivalent to 8.337 lb/gal (U.S.). Therefore, for a hydrocarbon or a petroleum fraction, the SG is defined as:

In the early years of the petroleum industry, the American Petroleum Institute (API) adopted the API gravity (°API) as a measure of the crude oil density. The API gravity is calculated from the following equation:

The API scale for gravity was adapted from the Baumé scale, developed in the late 18th century to be used in hydrometers for measuring even small differences in the specific gravity of liquids, using water as a reference material in these devices. A liquid with SG of 1 (i.e., water) has an API gravity of 10. One can note from Eq. 1 that liquid hydrocarbons with lower SGs have higher API gravities. The API of crude oils varies typically between 10 and 50, with most crude oils falling in the range of 20-45. Using API gravity, the conventional crude oils can be generally considered as light (°API>30), medium (30>°API>22), and heavy (°API<22).

Note that the relationship between °API and specific gravity is not linear. Therefore, the °API gravity of crude blends cannot be calculated by linear averaging of the component °APIs. Specific gravities of the components can be averaged, though, to determine the specific gravity of the resulting blend. In practice, averaging °APIs is usually accepted because the error involved in averaging is small.

Among the hydrocarbons, aromatic hydrocarbons have higher SG (lower °API) than paraffinic hydrocarbons with the same number of carbon atoms. For example, benzene has an SG of 0.883 (°API of 28.7), whereas n-hexane has an SG of 0.665 (°API of 81.3). Therefore, the heavy (high-density) crude oils tend to have high concentrations of aromatic hydrocarbons, whereas the light (low-density) crude oils have high concentrations of paraffinic hydrocarbons.

Viscosity

Viscosity

Viscosity, commonly depicted by the symbol μ, is a physical property of a fluid that describes its tendency/resistance to flow. A high-viscosity fluid has a low tendency to flow, whereas low-viscosity fluids flow easily. Newton’s Law of Viscosity provides a physical definition of viscosity. Power requirement to transport (e.g., to pump) a fluid depends strongly on the fluid’s viscosity. Interestingly, the viscosity of liquid decreases with increasing temperature, while viscosity of gases increases with increasing temperature. Among petroleum products, viscosity constitutes a critically important characteristic of lubricating engine oils. Viscosity of liquids is usually measured in terms of kinematic viscosity, which is defined as the ratio of absolute (dynamic) viscosity to absolute density (ν = μ/ρ). Kinematic viscosity is expressed in units of centistokes (cSt), Saybolt Universal seconds (SUS), and Saybolt Furol seconds (SFS). Values of kinematic viscosity for pure liquid hydrocarbons are usually measured and reported at two reference temperatures, 38°C (100°F) and 99°C (210°F) in cSt. However, different reference temperatures, such as 40°C (104 °F), 50 °C (122 °F), and 60 °C(140 °F), are also used to report kinematic viscosities of petroleum fractions. The viscosity of crude oils can be measured using a standard method (ASTM D2983).

Knowledge Check

What are ASTM, ISO, IP?

Pour Point

Pour Point

The pour point of a crude oil, or a petroleum fraction, is the lowest temperature at which the oil will pour or flow when it is cooled, without stirring, under standard cooling conditions. Pour point represents the lowest temperature at which oil is capable of flowing under gravity. It is one of the important low-temperature characteristics of high-boiling fractions. When the temperature is less than the pour point of a petroleum product, it cannot be stored or transferred through a pipeline. Standard test procedures for measuring pour points of crude oil or petroleum fractions are described in the ASTM D97 (ISO 3016 or IP 15) and ASTM D5985 methods. The pour point of crude oils relates to their paraffin content: the higher the paraffin content, the higher the pour point.

Knowledge Check

What are Waxes?

Concentration of Various Contaminants

Concentration of Various Contaminants

In addition to hydrocarbons, crude oil contains hetroatom (S, N, metals) species that need to be removed if their concentrations are higher than the specified thresholds. Other impurities in crude oil include salt and sediment and water. The acidity of crude oil is also important, particularly for concerns of corrosion in pipes or other process units. Carbon residue of a crude oil indicates the tendency to generate coke on heter tubes or rector surfaces. All of these contaminants and properties of crude oils are measured using standard methods, as described in this section.

Sulfur and Nitrogen Content

Sulfur and Nitrogen Content

Sulfur Content

Sulfur content of crude oils is the second most important property of crude oils, next to API gravity. Sulfur content is expressed as weight percent of sulfur in oil and typically varies in the range from 0.1 to 5.0%wt. The standard methods that are used to measure the sulfur content are ASTM D129, D1552, and D2622, depending on the sulfur level. Crude oils with more than 0.5%wt sulfur need to be treated extensively during petroleum refining. Using the sulfur content, crude oils can be classified as sweet (<0.5%wt S) and sour (>0.5% %wt S). The distillation process segregates sulfur species in higher concentrations into the higher-boiling fractions and distillation residua. Removing sulfur from petroleum products is one of the most important processes in a refinery to produce fuels compliant with environmental regulations.

Nitrogen Content

Nitrogen content of crude oils is also expressed as weight percent of oil. Basic nitrogen compounds are particularly undesirable in crude oil fractions, as they deactivate the acidic sites on catalysts used in conversion processes. Some nitrogen compounds are also corrosive. Crude oils with nitrogen contents greater than 0.25%wt need treatment in refineries for nitrogen removal.

Metals Content and Total Acid Number

Metals Content and Total Acid Number

Metals Content

Most common metals that are found in crude oil are included in organometallic compounds like nickel, vanadium iron and copper, ranging in concentration from a few ppm up to 1000 ppm by weight, depending on the source of crude oil. Similar to sulfur species, the metallic compounds tend to concentrate in the higher-boiling fraction of crude oil. Higher metal contents also require treatment during petroleum refining because of the corrosion activity of some metals and their tendency to accumulate on catalyst surfaces, thus deactivating the catalysts in a number of refinery processes. Metal content can be measured using a standard EPA Method 3040.

Total Acid Number

Acidity of crude oil is measured by titration with potassium hydroxide (KOH), using the standard method ASTM D664. The measured acidity is expressed as the Total Acid Number (TAN) that is equivalent to milligrams of KOH required to neutralize 1 gram of oil. This number is particularly important to control corrosion in the distillation columns through selection of corrosion-resistant alloys for surfaces that come into contact with oil.

Carbon Residue, Basic Sediment and Water, and Salt Content

Carbon Residue, Basic Sediment and Water, and Salt Content

Carbon Residue

Carbon residue (as % wt of crude oil, or crude oil fraction) is determined as the weight of solid residue remaining after heating crude oil to coking temperatures (700-800°C). Two standard tests with slightly different procedures are used to measure carbon residue: ASTM D524 Ramsbottom Carbon Residue (RCR) and ASTM D189 Conradson Carbon Residue (CCR). Carbon residue relates to asphalt (or asphaltenes) content of oil and indicates the tendency of fouling in heater tubes and catalyst deactivation. The higher the carbon residue, the higher is the coking (fouling) propensity of crude oil.

Basic Sediment and Water (BS&W)

The standard method ASTM D4007 is used to measure the amount of suspended inorganic solid particles and water (BS&W) in crude oils. These contaminants are mixed with the oil during production, and high concentration of BS&W causes operational problems in a refinery.

Salt Content

Salt content of crude oils can be measured using the standard method ASTM D3230 and reported as lb NaCl/1000 bbl. Desalting (removing the salt) is necessary when NaCl content is greater than 10 lbs/1000 bbl. Such high salt contents lead to corrosion in distillation towers and other equipment.

Distillation and Boiling Points

Distillation and Boiling Points

The boiling point of a pure compound in the liquid state is defined as the temperature at which the vapor pressure of the compound equals the atmospheric pressure or 1 atm. The boiling point of pure hydrocarbons depends on carbon number, molecular size, and the type of hydrocarbons (aliphatic, naphthenic, or aromatic) as discussed in Lesson 1. Figure 2.1 shows the boiling points of n-alkanes as a function of carbon number.

Complex mixtures such as crude oil, or petroleum products with thousands of different compounds, boil over a temperature range as opposed to having a single point for a pure compound. The boiling range covers a temperature interval from the initial boiling point (IBP), defined as the temperature at which the first drop of distillation product is obtained, to a final boiling point, or endpoint (EP) when the highest-boiling compounds evaporate. The boiling range for crude oil may exceed 1000 °F.

The ASTM D86 and D1160 standards describe a simple distillation method for measuring the boiling point distribution of crude oil and petroleum products. Using ASTM, D86 boiling points are measured at 10, 30, 50, 70, and 90 vol% distilled. The points are also frequently reported at 0%, 5%, and 95% distilled. ASTM D1160 is carried out at reduced pressure to distill the high-boiling components of crude oil. As an alternative method, distillation data can be obtained by gas chromatography (GC), in which boiling points are reported versus the weight percent of the sample vaporized. This test method described in ASTM D2887 is called simulated distillation (SimDis).

Average Boiling Points

Average Boiling Points

Average boiling points are useful in predicting physical properties and for characterization of complex hydrocarbon mixtures. The key here is to represent a mixture of compounds with a range of boiling points by a single characteristic boiling point. Since this is a formidable task, there are five different “average boiling points” that are used in different correlations. They are:

1, 2, and 3 can be defined for a mixture of n components as:

where ABP is is expressed as VABP, MABP, or WABP and xi is the corresponding volume, mole, or weight fraction of component i, and Tbi is the normal boiling point of component i. Cubic average boiling point (CABP) and Mean Average Boling Points (MeABP) can be calculated as follows.

For petroleum streams, volume, weight, or mole fractions of the components are not usually known. In this case, VABP is calculated from standard distillation (ASTM D86 Method) data, and empirical relationships (charts, or equations) are used to calculate the other average boiling points.

Here is the procedure:

Equation 1 (Ts are ASTM D86 temperatures for 10, 30, 50, 70, and 90% volume distilled, respectively):

Along with VABP, the slope of the ASTM D86, SL, is used for converting VABP to other average boiling points.

Equation 2:

The following empirical equations can, then, be used to obtain the temperature difference (ΔT) between VABP and other average boiling points (ABP) [2] :

Equation 3:

Equation 4:

Equation 5:

Equation 6:

and

Equation 7:

The temperature unit used for VABP, SL, and ΔT in these correlations is Kelvin.

The following script can be used to calculate VABP, MeABP by entering the distillation temperatures in the table.

You may also use the charts in Figure 4.1a and Figure 4.1b (p. 39) of your textbook [3] to obtain MeABP and MABP, respectively, from VABP. Note that the slope of the distillation curve used in those charts refers to True Boiling Point (TBP) distillation (not to ASTM distillation), and it is calculated as (T70% -T10%)/60.

[3] Petroleum Refining, by J. H. Gary, G. E. Handwerk, M. J. Kaiser, 5th Edition, CRC Press NY, 2007, Chapter 4, p.39.

Crude Assay

Crude Assay

Crude oil assay consists of a compilation of data on properties and composition of crude oils. The assay provides critical information on the suitability of crude oil for a particular refinery and estimating the desired product yields and quality. It also indicates how extensively a given crude oil should be treated in a refinery to produce fuels that are in compliance with environmental regulations. A typical crude assay should include the following major specifications:

- API Gravity

- Total Sulfur (% wt)

- Pour Point (°C)

- Viscosity @ 20°C (cSt)

- Viscosity @ 40°C (cSt)

- Nickel (ppm)

- Vanadium (ppm)

- Total Nitrogen (ppm)

- Total Acid Number (mgKOH/g)

- Distillation Data

- Characterization factor KUOP, KW

Characterization Factors

Characterization Factors

Since the early days of the petroleum industry, some physical properties of crude oil were used to define characterization factors for classification of crude oil with respect to hydrocarbon types [4] as shown in Equation 8.

where: Tb = volume, or mean average normal boiling point in R (degree Rankine) and SG = specific gravity at 15.6°C (60°F). To calculate KUOP or KW, volume average boiling point (VABP) or mean average boiling point is used, respectively. Depending on the value of the Watson characterization factor, crude oils are classified as paraffinic (Kw = 11-12.9), naphthenic (Kw =10-11), or aromatic (Kw <10).

Another parameter defined in the early years of petroleum characterization is the viscosity gravity constant (VGC). This parameter depends on viscosity expressed in Saybolt Universal Seconds (SUS) and specific gravity. According to a standard method (ASTM D2501), VGC can be calculated at a reference temperature of 100°F as follows in Equation 9:

where V(100°F) is the viscosity in SUS and SG is the specific gravity at 15.6°C (60°F). VGC varies between 0.74 to 0.75 for paraffinic, 0.89 and 0,94 for naphthenic, and 0.95 and 1.13 for aromatic hydrocarbons.

The U.S. Bureau of Mines Correlation Index (BMCI) or (CI) is useful for characterization of crude oil fractions. CI is defined in terms of Mean Average Boiling Point (Tb) and specific gravity (SG) at 60°F as shown in Equation 10:

According to this CI scale, all n-paraffins have a CI value of 0, while cyclohexane (the simplest naphthene), has a CI value of 50, and benzene has a CI value of 100. Using the CI values, crude oils can be classified as follows:

| paraffinic | CI<29.8 |

|---|---|

| naphthenic | CI<57.0 |

| aromatic | CI>75.0 |

[4] K. M. Watson, E. F. Nelson , George B. Murphy, “Characterization of Petroleum Fractions,” Ind. Eng. Chem., 1935, 27 (12), pp 1460–1464

Elemental Analysis and Ternary Classification of Crude Oils

Elemental Analysis and Ternary Classification of Crude Oils

Despite a wide variety of crude oil found in different parts of the earth, the elemental composition of most crude oils changes in narrow ranges, as shown in Table 2.2.

| Element | % Wt |

|---|---|

| C | 84-86% |

| H | 11-14% |

| S | 0-6% |

| N | 0-1% |

| O | 0-2% |

With such narrow ranges of change in elemental contents, elemental composition does not have much utility for classification of crude oil. Instead, variations in hydrocarbon composition (paraffins, naphthenes, and aromatics) are used to classify crude oils, using a ternary diagram, shown in Figure 2.2. Each apex of the triangle represents 100 percent weight of the corresponding compounds, and 0% of this particular type of hydrocarbons on the side of the triangle across from the apex. For example, the side at the bottom of the triangle (across from the apex of 100% aromatics) represents binary mixtures of paraffins and naphthenes.

If you need to refresh your memory on reading ternary diagrams, you may check "Reading a Ternary Diagram [11]", or consult other sources. The list below shows the six classes of crude oil that are defined using a ternary diagram. These classes are shown as areas on the ternary diagram for paraffins, below. It is generally accepted that Class 1 (rich in paraffins) represents the most desirable type of crude oil because refining these crudes would readily lead to high yields of light and middle distillates that constitute the fuels such as gasoline, diesel fuel, and jet fuel which are in high demand. Extensive refining would be required to produce high yields of distillate fuels from aromatic crudes (e.g., Class 4-6). Class 1 crudes tend to have high °API and low sulfur contents and tend to be more expensive than the other types of crude oils.

Ternary Classification of Crude Oils

- Paraffinic Crudes

paraffins + naphthenes > 50%

paraffins > naphthenes

paraffins > 40% - Naphthenic Crudes

paraffins +naphthenes > 50%

naphthenes > paraffins

naphthenes > 40% - Paraffinic-Naphthenic Crudes

Aromatics < 50%

paraffins < 40%

naphthenes < 40% - Aromatic-Naphthenic Crudes

Aromatics > 50%

naphthenes > 25%

paraffins < 10% - Aromatic-Intermediate Crudes

Aromatic > 50%

paraffins > 10% - Aromatic-Asphaltic Crudes

Naphthenes < 25%

paraffins < 10%

Video: Lesson 2 Paraffins (2:47)

Video: Lesson 2 Aromatics (2:34)

Self-Check Questions

Self-Check Questions

Take a few minutes to answer the questions below. When you are ready, Click Check to see the solutions.

Assignments

Assignment Reminder

Each week, you will have a number of assignments. This week's assignments are listed below. All assignments are submitted in Canvas. For due dates, please check your syllabus.

- Quiz 1 is due next Monday. Quiz 1 will cover material in both Lessons 1 and 2.

- Exercise 1 is due this week. Read the instructions carefully on what is acceptable.

Quiz 1

Quiz 1 is located in the Quizzes folder in Canvas. Quiz 1 will cover material in Lessons 1 and 2.

Exercise 1

Exercise 1 Instructions

Exercise 1 is provided in Canvas module Lesson 2 as a downloadable file. Submit your answers as a file in PDF format the Exercise 1 assignment in the Lesson 2 Module. For all the exerciase in this course, please make sure that you clearly indicate all the steps that you use to solve the problems and submit your own work.

Please note:

Scans of handwritten pages are not acceptable.

Summary and Final Tasks

Lesson 2 Summary

Selected properties of crude oil provide information on its quality and the conditions for optimum operation of a petroleum refinery for processing the crude oil to produce the desired fuels. Readily measurable physical properties of crude oil (such as density, boiling point, and viscosity) not only help predict the physical behavior of crude oil during refining but also give insight into the chemical composition of the oil. Therefore, physical properties can be used in developing characterization factors that relate to the chemical behavior of crude oil and the characteristics of the resulting refinery products. In addition to using characterization factors, crude oils are classified using ternary diagrams reflecting the hydrocarbon composition in terms of paraffins, naphthenes, and aromatics.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- define the significant properties of crude oil, including density, viscosity, average boiling point, sulfur, and salt content;

- understand the significance of crude oil properties in terms of refinery objectives, and describe crude oil assay;

- define and interpret the classification factors (Watson, UOP, VGC, and BMCI) as they relate to the hydrocarbon composition of crude oils;

- calculate average boiling points for crude oils using different averaging techniques, and differentiate Watson and UOP characterization factors;

- analyze the elemental composition of crude oils and outline ternary classification of crude oils with respect to hydrocarbon composition, i.e., aromatics, paraffins, and naphthenes;

- assess the use of ternary classification of crude oils to estimate the refinery product yields.

Reminder - Complete all of the Lesson 2 tasks!

You have reached the end of Lesson 2! Double-check the to-do list below to make sure you have completed all of the activities listed there before you begin Lesson 3. Please refer to the Course Syllabus for specific time frames and due dates. Specific directions for the assignment below can be found within this lesson.

| Readings | J. H. Gary, G. E. Handwerk, Mark J. Kaiser, Chapter 3, pp. 57-61, 65-70 and the course material from this site |

|---|---|

| Assignments | Exercise 1 - Submit to the Exercise 1 Assignment in the Lesson 2 Module.

|

Questions?

If you have any questions, please post them to our Help Discussion Forum (not email), located in Canvas. I will check that discussion forum daily to respond. While you are there, feel free to post your own responses if you, too, are able to help out a classmate.

Lesson 3: Overall Refinery Flow

Lesson 3 Overview

Overview

Video: FSC 432 Lesson 3 (2:16)

Overview

Selected properties of crude oil provide information on its quality and the conditions for the optimum operation of a petroleum refinery for processing the crude oil to produce the desired fuels. Readily measurable physical properties of crude oil (such as density, boiling point, and viscosity) not only help in predicting the physical behavior of crude oil during refinery but also give insight into the chemical composition of the oil. Therefore, physical properties can be used in developing characterization factors that relate to the chemical behavior of crude oil and the characteristics of the resulting refinery products. In addition to using characterization factors, crude oils are classified using ternary diagrams reflecting the hydrocarbon composition in terms of paraffins, naphthenes, and aromatics.

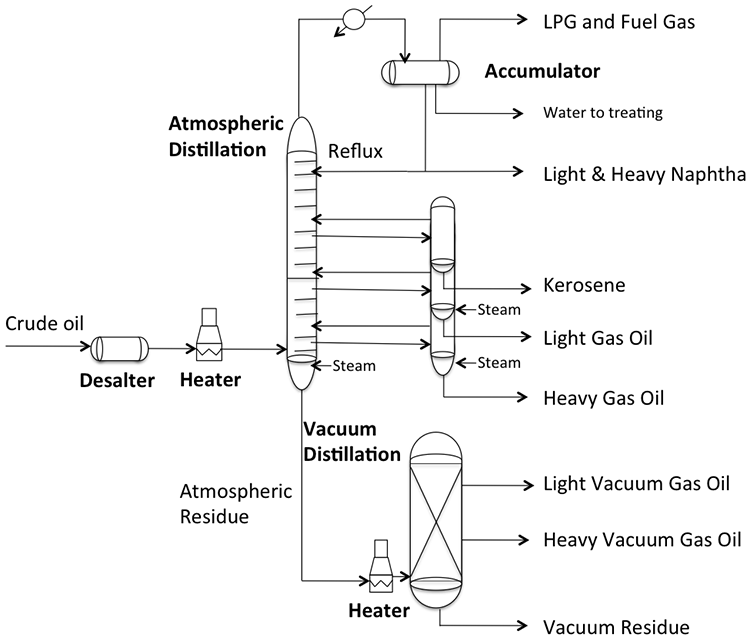

As introduced in Lesson 1, petroleum refining integrates four types of processes: separation, conversion, finishing, and supporting processes. This lesson involves a quick walk through a simple refinery in the U.S. to see what happens to a barrel of crude oil, and to provide more detail on how different processes are sequenced for optimum operation. The simple animation below shows a simplified diagram of processing network to maximize gasoline yield and produce the other distillate fuels (jet fuel, diesel fuel, and fuel oil) in high yield.

The first sequence of processes in a refinery makes use of physical separation to wash the salt out and to fractionate the desalted crude into different boiling ranges in a distillation column. Following the distillation, these fractions are subjected to further separation processes, such as those in Light Ends Unit (LEU) dewaxing and deasphalting units; to finishing processes, such as hydrotreatment; and to conversion processes, such as catalytic cracking, hydrocracking, visbreaking, and delayed coking. As shown in the animation below, the final products from these processes include Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG), lubricating oil base stock, asphalt, jet fuel and diesel fuel, gasoline, fuel oil, and petroleum coke. Some fractions from LEU are sent to finishing processes (blending and hydrotreatment) and further to a conversion process (reforming) to produce additional gasoline. Light products from catalytic cracking are subjected to further conversion in the alkylation process to produce more gasoline. Finally, supporting processes, hydrogen production and sulfur recovery, help remove the major heteroatom contaminant, sulfur, from the petroleum fuels through hydrotreatment [1].

This refinery scheme is typical in U.S. refineries where the premium product is gasoline, as one could tell from the number of processes that lead to gasoline as the major product. The gasoline streams from different processes are blended in sophisticated linear and non-linear programming schemes to produce the three grades of gasoline sold in the U.S., regular, intermediate, and premium grades defined in reference to octane number. Elsewhere in the world, there is more emphasis on producing diesel fuel rather than gasoline, since the transportation systems are not as heavily dependent on gasoline-powered passenger vehicles. Diesel fuel is preferred for mass transport options (e.g., buses and trains), as diesel engines (with compression-ignition) can deliver more power than spark-ignition gasoline engines.

In the following sections, each major process group in a refinery network will be introduced in sequence. We will discuss how they fit in the “industrial ecology” of petroleum refining for the overall economic goal of maximizing profit in the prevailing markets for crude oil and the refined petroleum products. The video below presents a flow diagram integrating the four types of processes in a petroleum refinery.

Video: FSC 432 Simple Refinery Flow (4:36)

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- illustrate the refinery processes with examples for each category of processes;

- distinguish and evaluate the functions of different refinery processes to control refinery product yield and composition;

- evaluate the principles behind the major refinery processes and examine the products from each process from Distillation to Hydrocracking;

- formulate strategies for upgrading heavy oil.

What is due for Lesson 3?

This lesson will take us one week to complete. Please refer to the Course Syllabus for specific time frames and due dates. Specific directions for the assignments below can be found on the Assignments page within this lesson.

| Readings: | J. H. Gary, G. E. Handwerk, & Mark J. Kaiser, Chapter 1, pp. 32-36; Chapter 2, pp. 41-55 and the course material from this site |

|---|---|

| Assignments: | Exercise 2: Using ternary classification to characterize crude oil blends |

Questions?

If you have any questions, please post them to our Help Discussion (not email), located in Canvas. I will check that discussion forum daily to respond. While you are there, feel free to post your own responses if you, too, are able to help out a classmate.

Desalting and Distillation

Desalting and Distillation

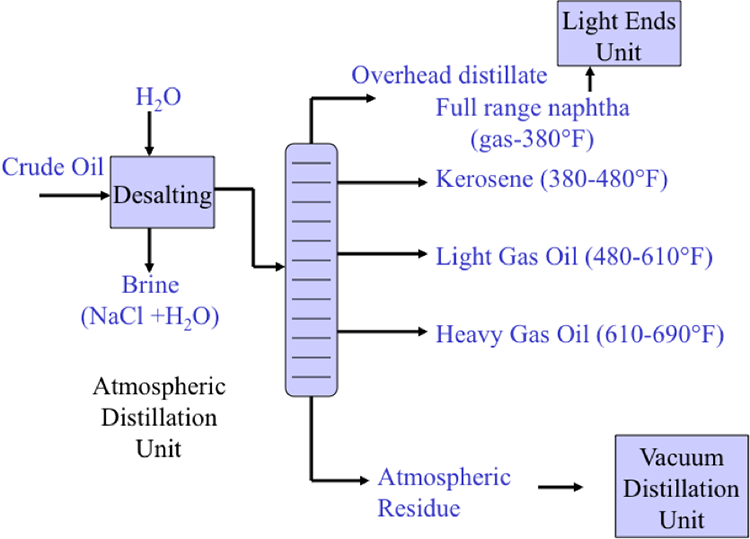

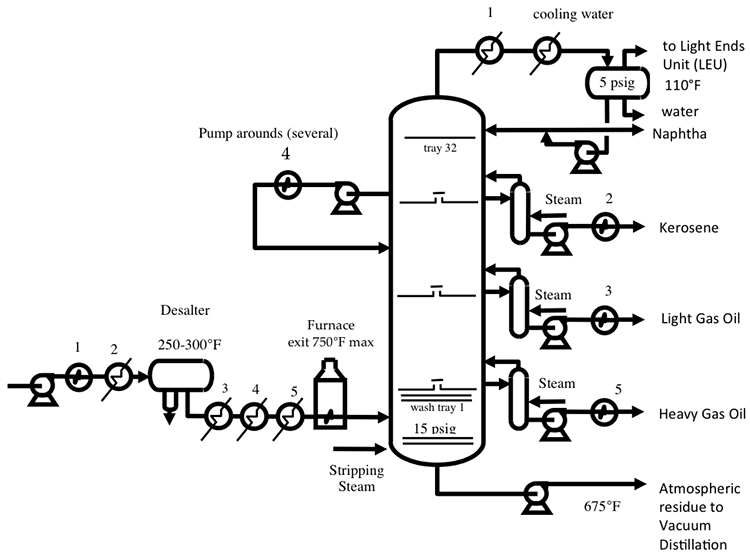

Although distillation is usually known as the first process in petroleum refineries, in many cases, desalting should take place before distillation (Figure 3.1). Salt dissolved in water (brine) enters the crude stream as a contaminant during the production or transportation of oil to refineries. If salt is not removed from crude oil, serious damage can result, especially in the heater tubes, due to corrosion caused by the presence of Cl. Salt in crude oil also causes reduction in heat transfer rates in heat exchangers and furnaces.

The three stages of desalting are:

- adding dilution water to crude;

- mixing dilution water with crude by a mixer;

- dehydration of crude in a settling tank to separate crude and sediment and water (S&W).

Desalting can be performed in a single-stage or two-stage units. The amount of water wash and the temperature of the mixing process depends mainly on the crude API gravity [2].

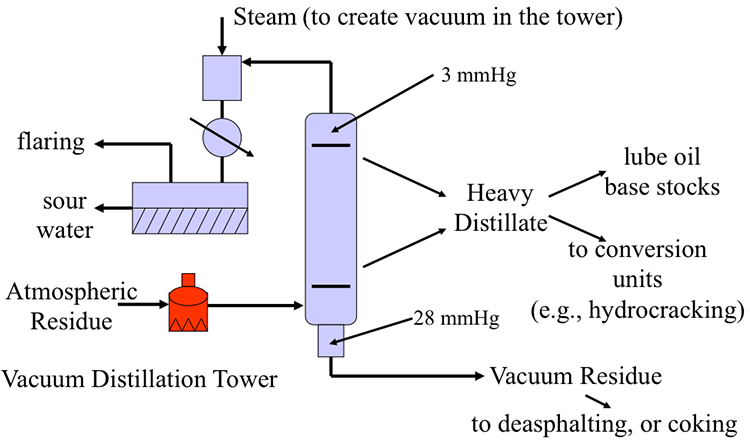

Distillation separates hydrocarbon compounds into distillate fractions based on their boiling points or volatility. More volatile compounds (with low boiling points) tend to vaporize more readily than heavy compounds, and this forms the basis of separation through distillation. In a distillation column, light components are removed from the top of the column, and the heavier part of the mixture appears in the bottom. For a crude that is a mixture of thousands of hydrocarbons, some very light compounds such as ethane and propane only appear in the top product, while extremely heavy and non-volatile compounds such as asphalts only appear in the bottom. Figure 2 shows a simple diagram of atmospheric and vacuum distillation units and the fractional separation of the crude oil into different boiling fractions with the indicated boiling ranges. The lightest compounds found in crude oil come out from the top of the distillation column (referred to as overhead distillate, or full-range naphtha) and are sent to the Light Ends Unit (LEU) for further separation into LPG and naphtha, as discussed later. The side streams separated in the atmospheric distillation column give fractions that include the “straight-run” products called kerosene, and light and heavy gas oils. The residue from the atmospheric distillation column generates two side streams, light and heavy vacuum gas oils, and vacuum residue from the bottom. All of these distillation products are subjected to subsequent processing to produce light and middle distillate fuels and non-fuel products, as described in the following sections, starting with LEU.

Light Ends Unit

Light Ends Unit

As shown in Figure 3.2, the Light Ends Unit consists of a sequence of distillation processes to separate the overhead distillate product from the atmospheric distillation column into five streams consisting of methane and ethane (C2 and lighter), to propane (C3), butane (C4), light naphtha, and heavy naphtha. The fraction C2 and lighter is used as fuel gas in the refinery to provide heat or generate steam. Propane and butane are sold as liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) after removing H2S. Light naphtha fraction that consists of C5 and C6 paraffins (pentane and hexane) is sent to the gasoline blending pool as straight-run gasoline, while the heavy naphtha fraction (rich in cycloalkanes, or naphthenes) is sent to a catalytic reforming process to produce gasoline with a high octane number.

Catalytic Reformer

Catalytic Reformer

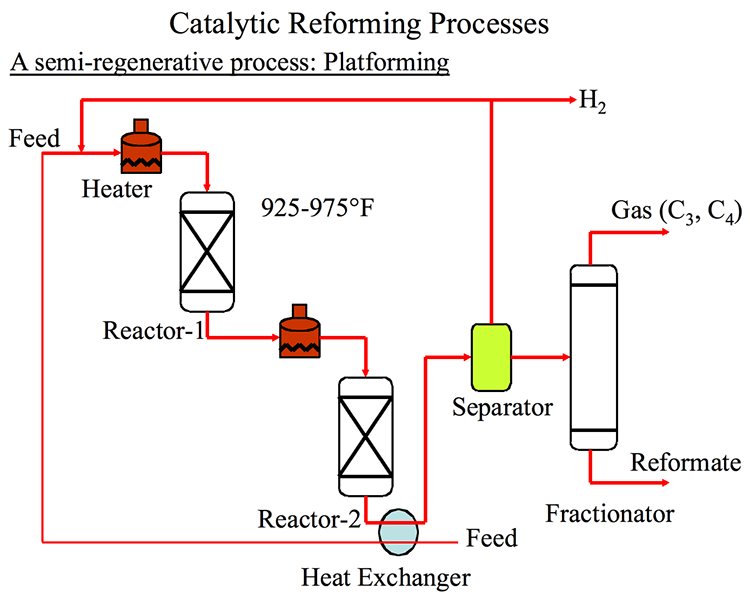

Catalytic reforming converts low-octane straight run naphtha fractions (particularly heavy naphtha that is rich in naphthenes) into a high-octane, low-sulfur reformate, which is a major blending product for gasoline (Figure 3.3). The most valuable byproduct from catalytic reforming is hydrogen, which is needed in refineries with increasing demand for hydrotreating and hydrocracking processes. Most reforming catalysts contain platinum supported on alumina, and some may contain additional metals such as rhenium and tin in bi-, or tri-metallic catalyst formulations. Early reforming processes were called platforming in reference to reforming with a platinum catalyst. In most cases for catalytic reforming, the naphtha feedstock needs to be hydrotreated before reforming, to protect the platinum catalyst from poisoning by sulfur or nitrogen species. The principal reactions in catalytic reforming include dehydrogenation of naphthenes to aromatics (with significant quantity of hydrogen as byproduct) and cracking/isomerization of n-paraffins into i-paraffins. The principal product from catalytic reforming is called reformate, consisting of C4 to C10 hydrocarbons. Reformate has a high octane number because of high concentration of aromatic compounds (benzene, toluene, and xylene) produced from naphthenes. With the more stringent requirements on benzene and total aromatics limit in US and Europe (less than 1% benzene, 15% total aromatics), the amount of reformate that can be used in gasoline blending has been limited, but the function of catalytic reforming as the only internal source of hydrogen continues to be important for refineries.

Catalytic Hydrotreatment

Catalytic Hydrotreatment

As seen with the catalytic reforming in the previous section, catalytic hydrotreatment can be used as a pretreatment step to protect catalysts from crude oil contaminants such as heteroatom (S, N, O) compounds, as well as metals (mainly Ni, V). Hydrotreatment is also used as a major finishing process in a petroleum refinery. Shifting to the side stream products from the distillation column, kerosene and light gas oil fractions can be hydrotreated to remove the heteroatoms to produce the final products of jet fuel, and diesel fuel, as shown in Figure 3.4. Particularly strict sulfur limits are imposed on diesel fuels so that the particulate emissions from diesel engines can be reduced. In the U.S., the government regulations [3] require that highway and non-road locomotive and marine (NRLM) use diesel fuel that meets a maximum specification of 15 parts per million (ppm) sulfur by 2014, with a full compliance for highway use and non-road diesel fuel since December 2010. Note in Figure 5 that typical catalysts used for hydrotreating are Co and Mo compounds supported on alumina (Al2O3). Jet fuel consists of C10 to C15 hydrocarbons, and diesel fuel consists of C15 to C20 hydrocarbons. Analogous to octane number for gasoline, a performance parameter for diesel fuel is cetane number (n-C16H34, n-hexadecane) that measures, in contrast to octane number, the tendency (not resistance) of diesel fuel to ignite upon compression with air. As a side note, light gas oil fraction is not typically used in the U.S. for producing diesel fuel, but sent to catalytic cracking to make gasoline.

Conversion of Heavy Gas Oil

Conversion of Heavy Gas Oil

Moving down to the side streams of the distillation column, heavy gas oil constitutes the next fraction in line. Some generic conversion processes for the heavy distillates, such as heavy gas oil (consisting of C20 to C25 hydrocarbons), are shown in Figure 3.5. These processes, aimed at reducing the molecular size or the boiling point of gas oil compounds, involve thermal cracking or catalytic cracking. A mild thermal cracking process, called visbreaking, is applied to reduce the viscosity of the feedstock, and it is more frequently applied to residual fractions, such as vacuum distillation residue. A more severe thermal cracking of heavy gas oil can be used to produce LPG and ethylene and light and middle distillates from heavy gas oil. A highly aromatic byproduct from thermal cracking is called ethylene tar. Ethylene is an important petrochemical feedstock, while ethylene tar can be used as feedstock to produce carbon blacks. Catalytic cracking is more frequently used for conversion of heavy gas oil to gasoline.

A particular process of catalytic cracking, Fluid Catalytic Cracking, is almost exclusively used worldwide in heavy gas oil and light vacuum gas oil conversion. This process produces high octane gasoline primarily, with important byproducts, including LPG, light olefins and i-alkanes, light cycle oil (LCO), heavy cycle oil (HCO), and clarified slurry oil (also called decant oil), as shown in Figure 3.6. LCO is used in the U.S. to produce diesel oil by hydrocracking, and decant oil can be used as fuel oil, feedstock for carbon black manufacturing, and to produce a special type of petroleum coke called needle coke. Needle coke has a microstructure that makes it a good precursor to graphite electrodes that are used in electric-arc furnaces to recycle scrap iron and steel. The manufacturing of graphite electrodes, using a byproduct from FCC used to produce gasoline, is considered a principal interface between petroleum refining and the iron and steel industry.

Conversion and Processing of Vacuum Gas Oils

Conversion and Processing of Vacuum Gas Oils

Moving to the vacuum distillation column, the vacuum distillates, light vacuum gas oil (LVGO) and heavy vacuum gas oil (HVGO) can be processed by some advanced FCC processes. However, hydrocracking is more frequently used to convert LVGO and HVGO into light and middle distillates, using particular catalysts and hydrogen. Similar to LCO, the LVGO and HVGO fractions from vacuum distillation tend to be highly aromatic. Catalytic hydrocracking combines hydrogenation and cracking to handle feedstocks that are heavier than those that can be processed by FCC, because of excessive coke deposition on the catalyst in the absence of hydrogen. Middle distillates (e.g., kerosene and diesel fuel) are the principal products of hydrocracking. In addition to light and middle distillates, hydrocracking also produces light distillates and LPG, as shown in Figure 3.7.

HVGO can also be used as a feedstock to produce lubricating oil base stock, through a sequence of solvent extraction processes to remove aromatic hydrocarbons by furfural extraction, and to remove long-chain paraffins by dewaxing (Figure 3.8).

Processing and Conversion of Vacuum Distillation Residue

Processing and Conversion of Vacuum Distillation Residue

The heaviest and the most contaminated component of crude oil is the vacuum distillation residue (VDR), also referred to as the bottom-of-the-barrel. There are multiple processing paths to upgrade VDR into usable products. One process is called deasphalting, which removes the heaviest fraction of VDR as asphalt that is used mainly to pave roadways. The lighter fraction obtained in the deasphalting process, deasphalted oil (DAO), can be used as fuel oil after hydrotreatment (Figure 3.9).

Thermal processes, such as visbreaking and coking, also provide options for upgrading VDR, which is normally a solid at ambient temperature. As shown in Figure 3.10, the visbreaking operation involves mild thermal cracking, with the primary purpose of producing a relatively low grade fuel oil (with a much lower pour point than VDR) and byproducts such as middle and light (naphtha) distillates and LPG. The yield of these byproducts would normally not exceed 10%wt of VDR. As a general rule in refinery conversion processes, producing a lighter product with a higher H/C ratio (e.g., fuel oil, middle distillates, LPG) from a feedstock (e.g., VDR) would require the simultaneous formation of a heavier product (e.g., coke) with a lower H/C ratio than the feedstock. Clearly, this compensation is dictated by the hydrogen balance, or hydrogen distribution among the products. With no external hydrogen entering the conversion unit (as it would in hydrogenation, or hydrocracking reactions), making a product(s) with a higher H/C ratio than that of the feed would require making other product(s) with a lower H/C ratio than that in the feedstock. In the case of visbreaking, what enables the production of lighter (or lower viscosity) fuel oil and other products from VDR is the formation of small quantities of coke with an extremely low H/C ratio. Hence, the term disproportination describes this unequal distribution of C or H in the conversion products, or losing (rejecting) C in the coke that accumulates on reactor tubes and is periodically burned out to clean the reactor tubes.

As different from visbreaking, coking involves severe thermal cracking with intentional production of coke with a low H/C, so that lighter fuels can be obtained from VDR (by disproportionation), as can also be seen in Figure 3.10. The product coke obtained from VDR with relatively low heteroatom concepts, termed sponge coke, can be used in manufacturing carbon anodes that are used in electrolysis of alumina (Al2O3) to produce aluminum metal. This is another important interface between petroleum refining and metals industries, similar to the coke produced from decant oil used for making needle coke for manufacturing graphite electrodes to operate electric-arc furnaces, as mentioned before.

Paths for Upgrading Heavy Oil

Paths for Upgrading Heavy Oil

It should be clear from this quick tour of a refinery, that the most valuable products from a refinery include light distillates (gasoline) and middle distillates (jet fuel and diesel). These products are mostly paraffinic and contain relatively short paraffin chains, or small molecules, or, in other words, high H/C ratios. In this context, one could summarize the overall goal of petroleum refining as managing the H/C ratio of the products for the optimum distribution of hydrogen into products to maximize profits. Controlling the H/C ratio of the products would require either lowering the C content of the products (i.e., carbon rejection), or increasing the H content (i.e., hydrogen addition). The animation below depicts these two major paths for upgrading heavy oil (or crude oil) with some examples for each path. The processes, coking, solvent extraction (e.g., deasphalting), visbreaking, and catalytic cracking reject carbon in the coke (carbonaceous) product so that lighter products (with high H/C) ratios can be obtained in these processes. Carbon in the coke, or in the heavier product, is considered to have been rejected (and potentially lost) since the carbonaceous byproducts have much lower value in comparison to those of the lighter products. In contrast, hydrogen addition, as in the processes of hydrogenation and hydrocracking, enables the conversion of all the carbon present in heavy oil (or crude oil) to high value products without rejecting, or sacrificing, any. One might ask, then, why would any refinery carry out any carbon rejection process instead of hydrogen addition? A short answer to this question involves basic refinery economics; the hydrogen addition processes cost much more than carbon rejection processes, because producing hydrogen and the catalysts used in hydrogen addition processes are very expensive.

Video: FSC 432 Upgrading Heavy Oil (3:48)

Self-Check Questions

Self-Check Questions

Please take a few minutes to answer the following questions. When you are happy with your responses, click Check below.

Assignments

Assignment Reminder

Each week, you will have a number of assignments. This week's assignments are listed below with instructions on what to do. For due dates, please check your Syllabus.

Exercise 2

Exercise 2 Instructions

Exercise 2 is provided as a downloadable file in Canvas module Lesson 3. Please submit answers as a pdf to the Exercise 2 assignment in the Lesson 3 Module.

Please Note:

Scans of handwritten pages are not acceptable.

- A refinery has access to two different crude oil stocks A and B with the following compositions:

Table 3.1 Naphthenes % Aromatics % Crude A 30 65 Crude B 10 35 - What type of crude oils are A and B according to the ternary classification based on composition? 20 pts

- What type of crude would be obtained if A and B are blended in a proportion of A/B =3/2? 20 pts

- The refiners would like to maintain a weight ratio of 1/1, Crude A/Crude C in a ternary blend of the oils A, B, and C. What would be the minimum concentration of Crude B (% wt) in a ternary blend that could be classified as naphthenic oil? 60 pts

Table 3.2 aromatics naphthenes paraffins Crude A 70%wt 10%wt 20%wt Crude B 25%wt 60%wt 15%wt Crude C 15%wt 25%wt 60%wt

Instructions for Submitting Response:

Once you have a solution to the exercises, you will submit your answers as a PDF by uploading your file to be graded. The MS Word, or Excel files should be saved as a PDF before submitting the exercise. Please Note: Scans of handwritten pages are not acceptable.

Please follow the instructions below.

- Find the Exercise 2 assignment in the Lesson 3 Module.

- Make sure that your name is in the document title before uploading it to the correct assignment (i.e., Lesson3_Exercise2_Tom Smith).

Answers to Lesson 3 Exercise 2

Answers to Lesson 3 Exercise 2

Question 1

A refinery has access to two different crude oil stocks, A and B with the following compositions:

| Naphthenes % | Aromatics % | |

|---|---|---|

| Crude A | 30 | 65 |

| Crude B | 10 | 35 |

- What type of crude oils are A and B according to the ternary classification based on composition?

- What type of crude would be obtained if A and B are blended in a proportion of A/B =2/3?

Answer:

- What type of crude oils are A and B according to the ternary classification based on composition?

Aromatic-Naphthenic crude (Aromatics > 50% , Paraffins < 10 % )

Paraphinic crude ( P + N > 50 % , P >N , P > 40 % ) - What type of crude would be obtained if A and B are blended in a proportion of A/B =2/3?

In the blend with A/B = 2/3: A: 40%, B=60%

Binary Blend C: Naphthenes = (0.4)(30) + (0.6)(10) N= 18%

Aromatics = (0.4)(65) + (0.6)(35) = 30%, A=47%

Binary Blend C: Paraffinic-Naphthenic (A<50%, P<40, N<40%)

Question 2

The compositions of three crude oils available to a refinery are as follows:

Crude A: 60%wt paraffins, 20%wt naphthenes

Crude B: 50%wt aromatics, 30%wt paraffins

Crude C: 10%wt paraffins, 20%wt naphthenes

The refiners would like to maintain a weight ratio of 1/1, Crude A/Crude C in a ternary blend of the oils A, B, and C. What would be the minimum concentration of Crude B (% wt) in a ternary blend that could be classified as naphthenic oil?

Answer:

| aromatics | naphthenes | paraffins | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crude A | 70%wt | 10%wt | 20%wt |

| Crude B | 25%wt | 60%wt | 15%wt |

| Crude C | 15%wt | 25%wt | 60%wt |

Set A+B+C = 100 and A=C

Naphtene balance:

0.1(100-B)/2 + 0.6B + 0.25(100-B)/2 > 40

0.42B >22.5

B > 54 (approximately)

B>54, Therefore, B must be greater than 54% to maintain a naphthenic crude blend.

Here is a similar exercise you may want to work on before looking at the answers given here, including a graphical solution using the ternary diagram.

Question 1

A refinery has access to two different crude oil stocks, A and B with the following compositions:

| Naphthenes % | Aromatics % | |

|---|---|---|

| Crude A | 10 | 60 |

| Crude B | 60 | 10 |

- What type of crude oils are A and B according to the ternary classification based on composition?

- What type of crude would be obtained if A and B are blended in a proportion of A/B =2/3?

Answer:

- What type of crude oils are A and B according to the ternary classification based on composition?

Aromatic-Intermediate crude (Aromatics > 50% , Paraffins > 10 % )

Naphthenic crude ( P + N > 50 % , N > P , N > 40 % ) - What type of crude would be obtained if A and B are blended in a proportion of A/B =2/3?

In the blend with A/B = 2/3: A: 40%, B=60%

Binary Blend C: Naphthenes = (0.4)(10) + (0.6)(60) = 40%

Aromatics = (0.4)(60) + (0.6)(10) = 30%, P=30%

Binary Blend C: Border-line between Paraffinic-Naphthenic (A<50%, P<40, N<40%) and Naphthenic ((P+N>50%, N>P, N>40%) crude oils.

You may solve the problem graphically using a ternary diagram, as described below.

Video: FSC 432 Blend Triangle (4:43)

Question 2

The compositions of three crude oils available to a refinery are as follows:

Crude A: 60%wt paraffins, 20%wt naphthenes

Crude B: 50%wt aromatics, 30%wt paraffins

Crude C: 10%wt paraffins, 20%wt naphthenes

The refiners would like to maintain a weight ratio of 1/1, Crude B/Crude C in a ternary blend of the oils A, B, and C. What would be the minimum concentration of Crude A (% wt) in a ternary blend that could be classified as paraffinic oil?

Answer:

| aromatics | naphthenes | paraffins | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crude A | 20%wt | 20%wt | 60%wt |

| Crude B | 50%wt | 20%wt | 30%wt |

| Crude C | 70%wt | 20%wt | 10%wt |

Set A+B+C = 100g and B=C

Paraffin balance:

0.60A + 0.3(100-A)/2 + 0.1(100-A)/2 > 40

1.2A + 30 - 0 .3A + 10 - 0.1A >80

.8A > 40

A>50, Therefore, A must be greater than 50% to maintain a paraffinic crude blend.

Summary and Final Tasks

Petroleum refining may be considered as the most sophisticated scheme of integrated physical and chemical processes to meet the market demand for a number of fuels and materials in the economy. In addition to satisfying the performance specifications required by combustion engines, the composition of the produced fuels, such as gasoline, jet fuel, and diesel fuel, should be in compliance with environmental regulations. Considering that crude oil is a natural material that displays a wide range of variability in hydrocarbon composition and the distribution of heteroatom species, it is vital to practice an optimum sequence of the four types of processes that make up petroleum refining: separation, conversion, finishing, and support. These processes are integrated as an example of industrial ecology, such that every drop of crude oil ends up as a marketable product, including the contaminants such as sulfur. The U.S. refineries are configured to maximize the yield of gasoline (a light distillate) as the major product, along with jet fuel and diesel fuel (middle distillates). A number of processes produce different gasoline streams that are blended in sophisticated linear and non-linear programming schemes to produce the three grades of gasoline sold in the U.S. for profit. A quick walk through the network of refinery processes reveals the two general strategies that are in place to create the most value in the operation: carbon rejection and hydrogen addition. The balance between these two strategies hangs in the refinery economics and the markets for crude oil and refined petroleum products.

Learning Objectives

You should now be able to:

- illustrate the refinery processes with examples for each category of processes;

- distinguish and evaluate the functions of different refinery processes to control refinery product yield and composition;

- evaluate the principles behind the major refinery processes and examine the products from each process, from Distillation to Hydrocracking;

- formulate strategies for upgrading heavy oil.

Reminder - Complete all of the Lesson 3 tasks!

You have reached the end of Lesson 3! Double-check the to-do list below to make sure you have completed all of the activities listed there before you begin Lesson 4. Please refer to the Course Syllabus for specific time frames and due dates. Specific directions for the assignment below can be found within this lesson.

| Readings: | J. H. Gary, G. E. Handwerk, Mark J. Kaiser, Chapter 1, pp. 32-36; Chapter 2, pp. 41-55 and the course material from this site |

|---|---|

| Assignments: | Submit Exercise 2 as a PDF, or Excel file to the Exercise 2 assignment in the Lesson 3 Module. |

Questions?

If you have any questions, please post them to our Help Discussion (not email), located in Canvas. I will check that discussion forum daily to respond. While you are there, feel free to post your own responses if you, too, are able to help out a classmate.

Lesson 4: Separation Processes 1

Lesson 4 Overview

Overview

Video: FSC 432 Lesson 4 (2:23)

Overview

As introduced in Lesson 3, distillation is a key separation process that fractionates crude oil into a number of streams with specific boiling point ranges, or distillation cuts. Removing salt from crude oil usually precedes the distillation process to protect the downstream units from corrosion caused by Cl¯. Desalting process could also remove metals (e.g., Fe, Ni, V) and other inorganic solids and sediments that may deactivate catalysts used in conversion and finishing units. Depending on the specific gravity and the amount of salt present in a crude oil, refineries conduct from one up to three stages of desalting [1]. Heavy and crudes may require three stages of desalting, using processes such as gravity settling, electrostatic coalescence, and packed column separation [2]. Figure 4.1 shows a simple desalting process that uses gravity settling to separate brine (NaCl +H2O) from crude oil after diluting the crude with water and adding de-emulsifiers (chemical additives) to facilitate phase separation.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- compare and evaluate different distillation methods;

- define boiling point ranges (TBP) of distillation fractions of crude oil;

- identify and exemplify distillation terminology, including cut points and product yields in distillation ranges;

- illustrate the crude fractionation in Atmospheric Distillation and calculate the extent of separation between the distillation fractions;

- illustrate Vacuum Distillation and assess the application of Watson Characterization Factor to select the temperature in Vacuum Distillation Tower.

What is due for Lesson 4?

This lesson will take us one week to complete. Please refer to the Course Syllabus for specific time frames and due dates. Specific directions for the assignment below can be found on the Assignments page within this lesson.

| Reading | J. H. Gary, G. E. Handwerk, Mark J. Kaiser, Chapter 4 (Crude Distillation) |

|---|---|

| Assignments | Exercise 3: Appraisal of the degree of separation between distillation fractions Quiz 2: Will cover the material in Lessons 3-4. |

Questions?