Lesson 8: Catalytic Conversion Processes Part 2

Lesson 8 Overview

Overview

Video: FSC 432 Lesson 8 (7:52)

Hello. Welcome to lesson eight. We will talk about more catalytic conversion processes. We'll talk about in this class about alkylation, about polymerization, catalytic reforming, and isomerization. All of these processes are catalytic processes to produce high octane number gasoline.

Remember, for high performance, high power, we needed to produce high octane number gasoline. FCC obviously is the principal process in a refinery to produce high octane gasoline. Catalytic reforming, developed also during the Second World War, was really popular, very popular process.

Now the feed stock for catalytic cracking comes from the light ends unit. You'll remember the naphtha fractionater in the light ends unit. The heaviest product from the light ends unit is the heavy naphtha. The reason it's heavy-- it has a lot of naphthenes, or cycloalkanes in its composition.

So what happens in catalytic reforming, essentially converting these naphthenes or cycloalkanes into aromatics. Aromatics have very large octane numbers. Benzene, for example, has octane number of 100. So that it's highly, highly desirable high octane number component in the refinery blending scheme, if you will.

So dehydrogenation of naphthenes using a precious metal catalyst like platinum is pretty straightforward if you do have a clean heavy naphtha. If you have sulphur, associated with clean, or with naphtha feed, you need to hydro treat it to remove, because platinum is very susceptible to poisoning by sulphur. So you need a pre hydro treatment before catalytic reforming.

Now, up until 1990s, cat reforming was one of the most popular processes in the refinery as far as producing high octane number gasoline. But with the introduction of 1990 Clean Air Act amendments, the amount of gasoline or benzene and aromatics in gasoline were limited because of environmental issues or reasons of toxicity.

So all of a sudden now, catalytic reforming that produces a high aromatic content wasn't so desirable. But the refiners could not give up catalytic reforming. Why? Because there is a byproduct from cat reforming that is very, very valuable for the refinery. It has become, of course, increasingly valuable in the recent times. And that is hydrogen.

If you do dehydrogenate naphthenes, the byproduct is hydrogen, in addition to making aromatics. And hydrogen is needed in hydro treating processes and finishing processes that we will be talking about in the next lesson. So that is the cheapest source of hydrogen.

Obviously, you can make hydrogen from natural gas by reforming natural gas. And that is the done in refineries as well to produce additional hydrogen. But the cheapest source of hydrogen in a refinery comes from catalytic reforming. So it's still used in US refineries to make gasoline that is a reformate and, of course, the byproduct hydrogen.

The second process we will talk about this alkylation. Alkylation is, in a sense, the opposite of cracking, where you have a larger molecule, you crack it into smaller molecules. In Alkylation, we do the opposite. We take the smaller molecules and combine them into larger molecules that would fall in the boiling range for gasoline.

So the feed stocks for alkylation are three to four carbon atom alkanes, isoalkanes. Isobutane is the principal feed stock that comes from FCC. And also, olefins, three to four carbon atom olefins. That is propene and butene.

So combining isobutane with propene or butene will put you in the gasoline boiling range with seven to eight-carbon atoms. And the resulting product will be an isoalkane with a high octane number. That would be essentially making up the alkylate.

So alkylation is an alternative to catalytic reforming to make high octane gasoline without the aromatic. So that looks like really a nice alternative. But there is one problem. And the problem is for alkylation, you would need as catalyst highly concentrated acids, like highly concentrated sulfuric acid or highly concentrated hydrofluoric acid. These are, of course, not easy to our work with or transport or to have around, because of the risks involved with using this highly acidic materials.

Another process that generates larger hydrocarbons from smaller fragments are called polymerization. The difference between alkylation and polymerization is that we use just olefins in polymerization. No isobutane here.

So we use three to four carbon atom olefins-- typically again come from FCC process-- combine them using a milder acid as a catalyst this time-- so phosphoric acid. So the problems with handling phosphoric acids are not as severe as those with highly concentrated sulphuric or hydrogen fluoride used in alkylation. So polymerization produces branched olefins, which also have respectable octane numbers.

The last process we will talk about is isomerization. That's actually adding branching to straight-run paraffins. This is essentially the light naphtha that comes from the light end unit, as opposed to heavy naphtha that is naphthenic like naphtha is paraffinic. But it has only straight chain paraffins with low octane numbers. So isomerization add branching to these straight chains to increase the octane number. So all these processes just make high octane gasoline, which is, of course, the most important fuel in US refineries.

Overview

Among the catalytic conversion processes developed just before and during the Second World War are included, in addition to catalytic cracking, polymerization processes that were introduced in the mid- to late 1930s, and alkylation and isomerization processes that were developed in the early 1940s. The principal impetus for developing these processes was to meet the demand for high-octane-number gasoline required by the high compression gasoline engines, including those used in the aircraft. Catalytic reforming and catalytic isomerization were developed in the 1950s to increase the high-octane-number gasoline yields from refineries. These processes are still important in current refineries that are directed to maximize gasoline yield from the crude oil feedstock. By-products from some of these processes, such as LPG and hydrogen, have gained significance because of the increasing demand in modern refineries for LPG recently used as automobile fuel and for hydrogen to supply the increasing demand for hydrotreating and hydrocracking processes.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- locate the catalytic reforming process in the refinery flow diagram, summarize the process objectives and evaluate the chemical reactions that take place in catalytic reforming to realize the process objectives;

- identify the catalysts used for catalytic reforming, evaluate the reaction network and the activity of catalysts, and illustrate the desirable reactions with specific examples;

- outline the principles of thermodynamics, kinetics, and transport phenomena to formulate limits on reaction conditions for controlling desirable and undesirable reactions in catalytic reforming;

- assess the commercial catalytic reforming processes and compare catalyst regeneration practice in each process;

- place the alkylation process in the refinery flow diagram particularly in relation to FCC process and describe the purpose of alkylation;

- demonstrate alkylation reaction mechanisms and evaluate the use of concentrated acid catalysis of alkylation;

- demonstrate polymerization reaction mechanisms and compare alkylation and polymerization reactions and catalysis.

What is due for Lesson 8?

This lesson will take us one week to complete. Please refer to the Course Syllabus for specific time frames and due dates. Specific directions for the assignments below can be found on the Assignments page within this lesson.

| Readings: | J. H. Gary, G. E. Handwerk, Mark J. Kaiser, Chapters 10 (Catalytic Reforming and Isomerization)and 11(Alkylation and Polymerization) |

|---|---|

| Assignments: | Exercise 7 |

Questions?

If you have any questions, please post them to our Help Discussion (not email), located in Canvas. I will check that discussion forum daily to respond. While you are there, feel free to post your own responses if you, too, are able to help out a classmate.

Catalytic Reforming

Catalytic Reforming

Catalytic reforming converts low-octane, straight-run naphtha fractions, particularly heavy naphtha that is rich in naphthenes, into a high-octane, low-sulfur reformate, which is a major blending product for gasoline. The most valuable byproduct from catalytic reforming is hydrogen to satisfy the increasing demand for hydrogen in hydrotreating and hydrocracking processes. Most reforming catalysts contain platinum as the active metal supported on alumina, and some may contain additional metals such as rhenium and tin in bi- or tri-metallic catalyst formulations. In most cases, the naphtha feedstock needs to be hydrotreated before reforming to protect the platinum catalyst from poisoning by sulfur or nitrogen species. With the more stringent requirements on benzene and the total aromatics limit for gasoline in the United States and Europe, the amount of reformate that can be used in gasoline blending has been limited, but the function of catalytic reforming as the only internal source of hydrogen continues to be important for refineries.

Figure 8.1 locates the catalytic reforming process in a refinery. The feedstock for catalytic reforming is straight-run (directly from the crude oil) heavy naphtha that is separated in the naphtha fractionator of the Light Ends Unit, as discussed in Lesson 4. Light naphtha from the naphtha fractionator, inherently a low-octane-number fraction, can be sent directly to blending in gasoline pool after hydrotreating, if necessary, or sent to an isomerization process to increase its octane number. As discussed in Lesson 3, hydrotreating heavy naphtha is often necessary before catalytic reforming to protect the noble metal catalyst (e.g., Pt) used in the reforming process. The intended product from catalytic reforming is the high-octane-number reformate and the most significant by-product is hydrogen gas.

Chemistry of Catalytic Reforming

Chemistry of Catalytic Reforming

The general categories of the desired reactions in catalytic reforming are identified in the list below, along with the catalysts used in the process. Considering that the main purpose of the process is to increase the octane number of heavy naphtha, conversion of naphthenes to aromatics and isomerization of n-paraffins to i-paraffins are the most important reactions of interest. Under the right reaction conditions, aromatics in the feed, or those produced by dehydrogenation naphthenes, should remain unchanged. The reforming reactions produce large quantities of hydrogen, and one should remember that the dehydrogenation catalysts used in reforming can also catalyze hydrogenation and hydrocracking of aromatics during catalytic reforming. It is, therefore, important to keep these side reactions to a minimum by controlling the reactor conditions such as temperature and hydrogen pressure, as discussed in more detail later in this section.

The catalysts used in reforming contains platinum (Pt), palladium (Pd), or, in some processes, bimetallic formulations of Pt with Iridium or Rhenium supported on alumina (Al2O3).

Catalytic Reforming Reactions and Catalysts

Reactions of Interest

- naphthenes → aromatics

- paraffins are isomerized

- aromatics are unchanged

Catalysts Used

Platinum catalyst on metal oxide support (platforming)

Pt/Al2O3

Bimetallic – Iridium or Rhenium

Pt-Re/Al2O3

The information above shows the ranges of composition for feedstock heavy naphtha and the reformate product (high-octane gasoline). Comparing the compositions of the feedstock and the product, one can see that the largest change in feedstock composition is a substantial increase in the aromatics content of the feedstock, with attendant decreases in naphthene and paraffin contents to constitute the product.

Catalytic Reforming Feedstock and Product

|

Feedstock: Heavy Naphtha Paraffins ⇒ 45-55% Naphthenes ⇒ 30-40% Aromatics ⇒ 5-10% |

Product: High Octane Gasoline Paraffins ⇒ 30-50% Naphthenes ⇒ 5-10% Aromatics ⇒ 45-60% |

Low severity (relatively low octane) → low paraffin conversion

High severity → high paraffin conversion

Lean naphtha → high n-paraffinic content - difficult to process

Rich naphtha → low n-paraffinic (high naphthene) content - easy to process

The information above also defines some specific terms for catalytic reforming related to the feedstock composition (lean, or rich naphtha), or to the extent of n-paraffin conversion in the process (low-, or high-severity). One could conclude from these terms that reforming of heavy naphtha that contains higher n-paraffin content requires more severe conditions in the reactor.

Desirable Chemical Reactions

Desirable Chemical Reactions

Figure 8.2 illustrates more specifically the desirable chemical reactions of catalytic reforming, including:

- dehydrogenation of naphthenes to aromatics,

- dehydroisomerization of alkyl-C5-naphthenes,

- dehydrocyclization of n-paraffins to aromatics, and

- isomerization of n-alkanes to i-alkanes.

All of these reactions significantly increase the octane number (research octane number [RON] from 75 to 110 in Reaction 1, from 91 through 83 [cyclohexane] to 100 in Reaction 2, from 0 to 110 in Reaction 3, and from –19 to 90 in Reaction 4).

Reaction conditions that promote the desirable reactions are also listed in Figure 8.2. As can be seen in Figure 8.2, aromatic compounds and large quantities of by-product H2 are produced in the highly endothermic Reactions 1–3. High temperatures, low hydrogen pressures, low space velocity (SV), and low H2/HC ratio strongly promote the conversion in Reaction 1-3. Although maintaining a low hydrogen pressure is needed for promoting equilibrium conversion in Reactions 1-3, it is, however, necessary to maintain a sufficiently high hydrogen pressure in the reactors to inhibit coke deposition on the catalyst surfaces.

Undesired Reactions

Undesired Reactions

Hydrocracking is an undesired side reaction in catalytic reforming because it consumes hydrogen and decreases the reformate yield by producing gaseous hydrocarbons. Hydrocracking reactions are exothermic, but they can still be kinetically favored at high temperatures, and favored, obviously, by high hydrogen pressures. Below lists the heat of reactions for catalytic reforming reactions. Typically, reformers operate at pressures from 50 to 350 psig (345–2415 kPa), a hydrogen/feed ratio of 3–8 mol H2/mol feed, and liquid hourly space velocities of 1–3 h-1[1]. These conditions are chosen to promote the desired conversion reactions and inhibit hydrocracking while limiting coke deposition on the catalyst surfaces.

Undesired Reactions in Catalytic Reforming

Hydrocracking

n-C10+H2 → n-C6+n-C4

to inhibit this reaction, use

- high T

- high SV

- Low H2P

Catalytic reformers are normally run at low H2 pressure to inhibit hydrocracking!

Heats of Reactions:

paraffin to naphthene → 44 kJ/mol H2 - endothermic

naphthenes to aromatics → 71 kJ/mol H2 - endothermic

hydrocracking → -56 kJ/mol H2 - exothermic

Reaction Network

Reaction Network

A reaction network for catalytic reforming is shown in Figure 8.3 [2], indicating the role of metallic (M) and the acidic (A) sites on the support in catalyzing the chemical reactions. The surfaces of metals (e.g., Pt) catalyze dehydrogenation reactions, whereas the acid sites on the support (e.g., alumina) catalyze isomerization and cracking reactions. Metal and acid sites are involved in the catalysis of hydrocracking reactions. Achieving the principal objective of catalytic reforming—high yields and high quality of reformate—can be achieved, to a large extent, by controlling the activity of the catalysts and the balance between acidic and metallic sites to increase the selectivity to desirable reactions in the reaction network.

Catalytic Reforming Reaction network

KEY: R= Reversible, M = Metal Site, A=Acid Site

Lighter aromatics become alkylated aromatics (R)

-M/A (dealkylation)

Alkylated Aromatics become alkylated cyclohexanes (R)

-M (dehydrogenation)

Alkylated cyclohexanes become cyclopentanes (R)

-A

Cyclopentanes become n-paraffins (R)

-M/A (dehydrocyclization)

n-paraffins become i-paraffins (R)

-A (isomerization)

i-paraffins and n-paraffins to cracked products

-A (cracking)

Catalytic Reforming Processes

Catalytic Reforming Processes

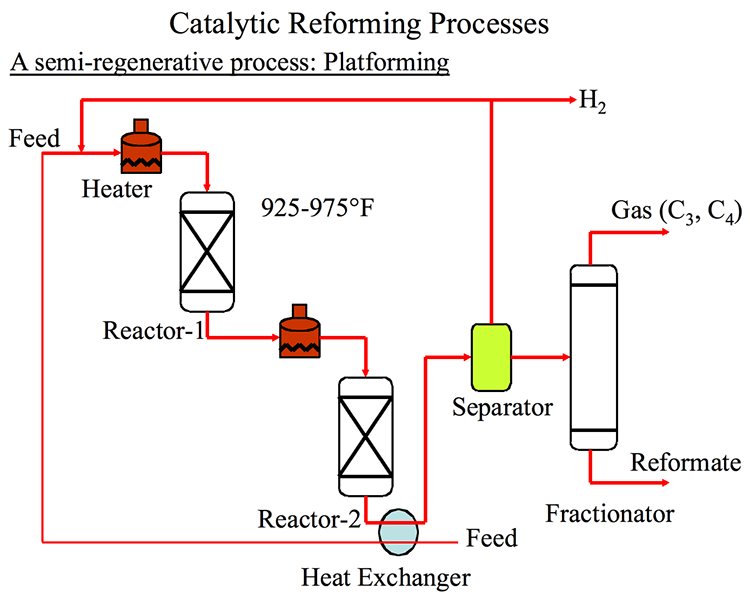

Even in the presence of hydrogen during reforming reactions, catalysts are deactivated by coke deposition. Commercial catalytic cracking processes are classified based on how catalysts are regenerated, as shown below, as semi-regenerative, cyclic, and continuous reforming processes. The first commercial catalytic reforming process was introduced by UOP in 1949 as the PlatformingTM process that used three fixed-bed reactors. Figure 8.4 (on next page), shows a process with two reactors. The reactors operate in series with furnaces placed before each reactor to heat the feedstock and the reactor effluents to 500–530°C before entering each reactor because the predominant reforming reactions are highly endothermic. These units, called “semi-regenerative catalytic reformers,” need to be shut down once every 6–24 months for the in-situ regeneration of catalysts that are deactivated by coke deposition. Later designs included an extra reactor (a swing reactor) to enable isolation of one reactor at a time to undergo catalyst regeneration, whereas the other three reactors are running (Cyclic). This configuration enables longer on-stream times (up to 5 years) before scheduled shutdowns for catalyst regeneration, but it has not become popular. In the HYSYS Project 2, you will be comparing the performance of the three different configurations of catalytic reforming processes.

Catalytic Reforming Processes

Catalytic Reforming Processes Based on Catalyst Regeneration

- Semi-regenerative (1949) – unit taken off-stream anywhere from every 3 to 24 months

- Cyclic (1960) – involves swing reactor. Basically, operate 3 out of 4 and use extra reactor to take one offline.

- Continuous (1971) – catalyst is removed and replaced during the operation. Maintains high activity. Expensive.

Licenced Processes (differences in catalysts and reactor configurations)

- Platforming (UOP process) (1949)

- Powerforming (Exxon)

- Ultraforming (Amoco)

- Catalytic Reforming (Engelhard)

- Magnaforming (Arco)

- Reforming (IEP)

- Rheniforming (Chevron)

Continuous Catalyst Regeneration

Continuous Catalyst Regeneration

A continuous catalyst regeneration (CCR) scheme for reforming came on stream in 1971. Figure 8.5 shows a flow diagram for the CCR process. The reactors are stacked with a moving bed of catalyst trickling from the top reactor to the bottom reactor by gravity. Partially deactivated catalyst from the bottom of the reactor stack is continuously withdrawn and transferred to the CCR regenerator. The regenerated catalyst is re-injected to the top of the first reactor to complete the catalyst circulation cycle. Hydrotreated naphtha feed is combined with recycled hydrogen gas and heat exchanged with the reactor effluent. The combined feed is then raised to the reaction temperature in the charge heater and sent to the first reactor section. Because the predominant reforming reactions are endothermic, an inter-reactor heater is used to reheat the charge to the desired reaction temperature before it is introduced to the next reactor. The effluent from the last reactor is heat exchanged with the combined feed, cooled, and separated into vapor and liquid products in a separator.

The vapor phase is rich in hydrogen gas, and a portion of the gas is compressed and recycled back to the reactors. Recycling hydrogen is necessary to suppress coking on the catalysts. The hydrogen-rich gas is compressed and charged together with the separator liquid phase to the product recovery section. The performance of the unit (i.e., steady reformate yield and quality) depends strongly on the ability of the CCR regenerator to completely regenerate the catalyst. In addition to UOP’s Platforming process, the major commercial catalytic reforming processes include PowerformingTM (ExxonMobil), UltraformingTM and MagnaformingTM (BP), Catalytic Reforming (Engelhard), Reforming (IFP), and RheniformingTM (Chevron).

The continuous catalytic reforming process starts at the heater, which goes to the reactor. From the reactor, it can either go back to the heater or move on. The spent catalyst exits and goes to a regenerator to regenerate the catalyst and burn off coke with air. The reformate continues to a low p separator and then a high p separator. Both separators give off H2 gas. Reformate excits and recycled H2 heads back to the heater. The temperatures are 925-975*F, Hydrogen – 4000-8000 scf/bbl fee, Pressure – 50-300 psig, LHSV – 2-3/hr.

Alkylation

Alkylation

The alkylation process combines light iso-paraffins, most commonly isobutane, with C3–C4 olefins, to produce a mixture of higher molecular weight iso-paraffins (i.e., alkylate) as a high-octane number blending component for the gasoline pool. Iso-butane and C3–C4 olefins are produced as by-products from FCC and other catalytic and thermal conversion processes in a refinery. The alkylation process was developed in the 1930s and 1940s to initially produce high-octane aviation gasoline, but later it became important for producing motor gasoline because the spark ignition engines have become more powerful with higher compression ratios that require fuel with higher octane numbers. With the recent restrictions on benzene and the total aromatic hydrocarbon contents of gasoline by environmental regulations, alkylation has gained favor as an octane number booster over catalytic reforming. Alkylate does not contain any olefinic or aromatic hydrocarbons.

Alkylation reactions are catalyzed by strong acids (i.e., sulfuric acid [H2SO4] and hydrofluoric acid [HF]) to take place more selectively at low temperatures of 70°F for H2SO4 and 100°F for HF. By careful selection of the operating conditions, a high proportion of products can fall in the gasoline boiling range with motor octane numbers (MONs) of 88–94 and RONs of 94–99 [15]. Early commercial units used H2SO4, but more recently, HF alkylation has been used more commonly in petroleum refineries. HF can be more easily regenerated than H2SO4 in the alkylation process, and HF alkylation is less sensitive to temperature fluctuations than H2SO4 alkylation [3]. In both processes, the volume of acid used is approximately equal to the volume of liquid hydrocarbon feed. Important operating variables include acid strength, reaction temperature, iso-butane/olefin ratio, and olefin space velocity. The reactions are run at sufficiently high pressures to keep the hydrocarbons and the acid in the liquid phase. Good mixing of acid with hydrocarbons is essential for high conversions.

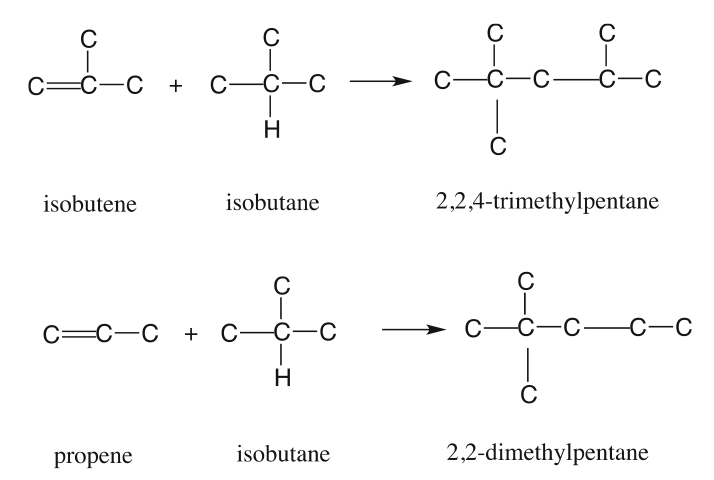

Some examples of desired alkylation reactions (combination of iso-paraffins with olefins) are given in Figure 8.6. These occur through ionic chain reactions (Figure 8.7) initiated by donation of a proton from the acid catalyst to an olefin to produce a carbocation that reacts with iso-butane to form a tert-butyl cation. Subsequent propagation reactions involve the reactions of a tert-butyl cation with olefins to form larger iso-paraffin cations that lead to final products through reactions with iso-butane to form a new tert-butyl cation to sustain the chain reaction [3]. The alkylation reaction is highly exothermic; therefore, cooling the reactor contents during alkylation is important.

UOP HF Alkylation Process

UOP HF Alkylation Process

Figure 8.8 shows a flow diagram for a UOP HF alkylation process [4]. Olefin and iso-butane feed streams are dried to remove water before they are mixed with the iso-butane recycle stream. The mixture is fed to the reactor, where it is highly dispersed into an incoming stream of acid catalyst. Conversion of reactants to high-quality alkylate takes place quickly, and the mixture flows up to the settling zone. In the settler, the catalyst is separated out as a bottom phase and flows, by gravity, through the catalyst cooler and returns to the reactor. The hydrocarbon phase from the settler, which contains propane, recycled iso-butane, normal butane, and alkylate, is charged to the main fractionator. High-purity propane is sent overhead to pass through the HF- propane stripper, de-fluorinator, and potassium hydroxide (KOH) treater before it is recovered. Recycled iso-butane is drawn from the side of the fractionator and returned to the entrance of the reactor after it is mixed with the dried olefin and isobutane feed. The n-butane product is taken from the side of the fractionators as vapor, condensed and KOH- treated before recovery. The alkylate product is obtained from the bottom of the fractionator. The HF catalyst is regenerated onsite in the regeneration section, where heavy oils (tars) are removed from the catalyst.

![UOP HF Alkylation Process [4]. More info in text above.](/fsc432/sites/www.e-education.psu.edu.fsc432/files/Lesson7/Lesson8Fig12.png)

Transporting and working with concentrated acids pose safety risks. In particular, HF tends to form a vapor cloud that is difficult to disperse. The major licensor of the HF alkylation processes is UOP, whereas ExxonMobil and Stratford Engineering Corporation license H2SO4 alkylation processes. A newly designed alkylation process by UOP uses a solid catalyst called Alkylene®. Advantages of this new process over traditional HF alkylation processes (liquid acid technology) include no acid transportation, no acid spills, no corrosion, and reduced maintenance cost. Efforts to develop alternative processes that use solid acid catalysts instead of concentrated HF and H2SO4 for alkylation are underway.

Polymerization

Polymerization

The polymerization process combines propenes and butenes to produce higher olefins with high-octane numbers (97 RON and 83 MON) for the gasoline pool. The polymerization process was used extensively in the 1930s and 1940s, but it was replaced to a large extent by the alkylation process after World War II. It has gained favor after phasing out the addition of tetraethyl lead (TEL) to gasoline, and the demand for unleaded gasoline has increased. Typical polymerization reactions are shown in Figure 8.9 [5].

The most commonly licensed polymerization process is the UOP polymerization process, which uses phosphoric acid as catalyst. IFP licenses a Dimersol® process that produces dimers from propene or butene using a homogeneous aluminum alkyl catalyst.

Isomerization

Isomerization

Isomerization processes have been used to isomerize n-butane to iso-butane used in alkylation and C5 /C6 n-paraffins in light naphtha to the corresponding iso-paraffins to produce high-octane number gasoline stocks after the adoption of lead-free gasoline. Catalytic isomerization processes that use hydrogen have been developed to operate under moderate conditions. Typical feedstocks for the isomerization process include hydrotreated light straight-run naphtha, light natural gasoline, or condensate. The fresh C5/C6 feed combined with make-up and recycled hydrogen is directed to a heat exchanger for heating the reactants to reaction temperature. Hot oil or high-pressure steam can be used as the heat source in this exchanger. The heated feed is sent to the reactor. Typical isomerate product (C5+) yields are 97 wt% of the fresh feed, and the product octane number ranges from 81 to 87, depending on the flow configuration and feedstock properties.

Self-Check Questions

Self-Check Questions

Before attempting to take the quiz this week, spend a few minutes answering the questions below. Make sure to click Check to see how well you understand the content.

Assignments

Assignment Reminder

Each week, you will have a number of assignments. This week's assignments are listed below with instructions on how and where to submit them. For due dates, please check your syllabus.

Exercise 7

Exercise 7 Instructions

Material Balance for FCC Regenerator

Problem

Burning the coke deposited on the catalyst particles generates all the heat necessary for catalytic cracking. Therefore, the coke burning rate is a critical parameter to control the rate of cracking. The composition of dry flue gas from the regenerator of an FCC unit is given in vol% as follows:

GasVolume %

N281.6

CO215.7

CO 1.5

O2 1.2

The dry air flow rate to the regenerator is given as 593 SCMM (standard cubic meters per minute). Considering that a significant portion of coke is carbon, you calculated in Exercise 6 the carbon burning rate in the regenerator as 52.6 kg/min.

For this exercise, calculate the coke burning rate in kg/min and the hydrogen content (wt%) of the coke burnt. Assume that the coke consists only of carbon and hydrogen.

Hint: Use an oxygen balance to determine the missing oxygen which was consumed to burn the hydrogen in coke. Water content of the flue gas is not given because only the dry gas analysis is reported.

Note: The assumption that “coke consists only of carbon and hydrogen” may be justified for gas oil feedstock that is virtually free of sulfur and other heteroatom species. For high sulfur feeds, sulfur content of the burnt coke can also calculated from the dry flue gas analysis.

Instructions for Submitting Response:

Once you have a solution to the exercises, you will submit your answers as a PDF by uploading your file to be graded. The MS Word, or Excel files should be saved as a PDF before submitting the exercise. Please Note: Scans of handwritten pages are not acceptable.

Please follow the instructions below.

- Find the Exercise 7 assignment in the Lesson 8 Module by either clicking Next until you find it or by clicking Assignments and scrolling down until you find it.

- Make sure that your name is in the document title before uploading it to the correct assignment (i.e. Lesson8_Exercise7_Tom Smith).

Summary and Final Tasks

Summary

Catalytic reforming, alkylation and polymerization processes aim at increasing the yield of high-octane-number gasoline in the refineries. Catalytic reforming uses naphthene-rich, straight-run heavy naphtha as feedstock and produces a high-octane number reformate for the gasoline blending pool in a refinery. Principal catalytic reactions that take place on noble metals (e.g., Pt) and on acidic catalyst supports (e.g., Al2O3) produce high yields of aromatic hydrocarbons and i-alkanes, respectively, to result in a high-octane number product. A valuable by-product from catalytic reforming is hydrogen gas for which the demand is increasing in the refineries, particularly for finishing processes, such as hydrotreatment. Alkylation and polymerization reactions take shorter chains of C3, C4 alkanes and olefins and combine them to get branched C7, C8 alkanes in alkylate, and polymerate, respectively, to increase the yield of high-octane gasoline. Isomerization processes convert n-butane to i-butane to be used as feed in alkylation processes, or isomerize n-C5 and n-C6 to the corresponding i-alkane to produce, again, high-octane-number gasoline stock.

Learning Outcomes

You should now be able to:

- locate the catalytic reforming process in the refinery flow diagram, summarize the process objectives and evaluate the chemical reactions that take place in catalytic reforming to realize the process objectives;

- identify the catalysts used for catalytic reforming, evaluate the reaction network and the activity of catalysts, and illustrate the desirable reactions with specific examples;

- outline the principles of thermodynamics, kinetics and transport phenomena to formulate limits on reaction conditions for controlling desirable and undesirable reactions in catalytic reforming;

- assess the commercial catalytic reforming processes and compare catalyst regeneration practice in each process;

- place the alkylation process in the refinery flow diagram particularly in relation to FCC process and describe the purpose of alkylation;

- demonstrate alkylation reaction mechanisms and evaluate the use of concentrated acid catalysis of alkylation;

- demonstrate polymerization reaction mechanisms and compare alkylation and polymerization reactions and catalysis.

Reminder - Complete all of the Lesson 8 tasks (Blog 8 and Quiz 4)!

You have reached the end of Lesson 8! Double-check the to-do list in the table below to make sure you have completed all of the activities listed there before you begin Lesson 9. Please refer to the Course Syllabus for specific time frames and due dates. Specific directions for the assignment below can be found within this lesson.

Questions?

If you have any questions, please post them to our Help Discussion (not email), located in Canvas. I will check that discussion forum daily to respond. While you are there, feel free to post your own responses if you, too, are able to help out a classmate.

| Readings: | J. H. Gary, G. E. Handwerk, Mark J. Kaiser, Chapters 10 (Catalytic Reforming and Isomerization)and 11(Alkylation and Polymerization) |

|---|---|

| Assignments: | Exercise 7 |