Lessons

Chapter 1: Location is Where It’s At: Introduction to GIScience and Technology

Overview

Have you ever found driving directions and maps online, used a smartphone to ‘check in’ to your favorite restaurant, or entered a town name or ZIP code to retrieve the local weather forecast?

Every time you and millions of other users perform these tasks, you are making use of Geographic Information Science (GIScience) and related spatial technologies. Many of these technologies, such as Global Positioning Systems (GPS) and in-vehicle navigation units, are very well known, and you can probably recall the last time you’ve used them.

Other applications and services that are the products of GIScience are a little less obvious, but they are every bit as ubiquitous. In fact, if you’re connected to the Internet, you’re making use of geospatial technologies right now. Every time your browser requests a webpage from a Content Delivery Network (CDN), a geographic lookup occurs, and the server you’re connected to contacts other servers that are closest to it and retrieves the information. This happens so that the delay between your request to view the data and the data being sent to you is as short as possible.

Simply put, GIScience and the related technologies are everywhere, and we use them every day!

In this chapter, you will learn about how location-based data makes GIScience possible; ways geographical data are used; geographical information systems (GIS) that have been developed to collect, store, analyze, and disseminate geographical information; the ways in which GIScience knowledge can contribute to careers as diverse as urban planning, information science, or public health, and the kinds of careers followed by those within GIScience itself.

Objectives

The goal of Chapter 1 is to introduce the many kinds of geographical information that permeate our daily lives and to situate that information and its uses within the larger enterprise known as Geographic Information Science and Technology (GIS&T), what the U.S. Department of Labor calls the "geospatial industry." In particular, students who successfully complete Chapter 1 should be able to:

- identify geographic data and what makes location-based data special;

- explain the qualities of a map and what separates maps from other graphics;

- recognize the sources of geographic data;

- describe the kinds of questions that GIS can help answer.

Chapter lead author: Joshua Stevens.

Portions of this chapter were drawn directly from the following text:

Joshua Stevens, Jennifer M. Smith, and Raechel A. Bianchetti (2012), Mapping Our Changing World, Editors: Alan M. MacEachren and Donna J. Peuquet, University Park, PA: Department of Geography, The Pennsylvania State University.

1.1 Geospatial Research, Careers, and Competencies

"A body of knowledge" is one way to think about the GIS&T field. Another way is as an industry made up of agencies and firms that produce and consume goods and services, generate sales and (sometimes) profits, and employ people. In 2003, the U.S. Department of Labor identified "geospatial technology" as one of 14 "high growth" technology industries, along with biotech, nanotech, and others. However, the Department of Labor also observed that the geospatial technology industry was ill-defined, and poorly understood by the public.

Subsequent efforts by the Department of Labor and other organizations helped to clarify the industry's nature and scope. Following a series of "roundtable" discussions involving industry thought leaders, the Geospatial Information Technology Association (GITA) and the Association of American Geographers (AAG) submitted the following "consensus" definition to the Department of Labor in 2006:

The geospatial industry acquires, integrates, manages, analyzes, maps, distributes, and uses geographic, temporal, and spatial information and knowledge. The industry includes basic and applied research, technology development, education, and applications to address the planning, decision-making, and operational needs of people and organizations of all types.

Currently, the Department of Labor recognizes 10 geospatial occupations: Surveyors, Surveying Technicians, Surveying and Mapping Technicians, Cartographers and Photogrammetrists, Geospatial Information Scientists and Technologists, Geographic Information Systems Technicians, Remote Sensing Scientists and Technologists, Remote Sensing Technicians, Precision Agriculture Technicians, and Geodetic Surveyors. Beyond these explicitly geospatial occupations, there are many others that rely heavily on geographical data and technology; these include urban and regional planning, many careers associated with location-based services, environmental management, landscape architecture and geo-design, transportation engineering, precision agriculture, and others. Still others use geographical data and technologies for selected tasks such as in public health (for infectious disease modeling and health care accessibility analysis), energy industries (to analyze distribution of oil and gas reserves or plan shipments), disaster management (to plan for and respond to events), and criminology (to identify crime hotspots and allocate patrols).

In addition to providing a wide array of occupational opportunities, the geospatial industry is considered a high growth industry. As of 2010, the US Employment and Training Administration is investing $260,000,000 through the WIRED (Workforce Innovation in Regional Economic Development) initiative to promote high-paying geospatial careers.

Although it is helpful to see how the Department of Labor and other agencies define the geospatial industry and how these occupations are expected to grow in the coming decade, many other careers and positions reliant on GIScience exist. Similar to how some geospatial technologies are well known while others operate behind the scenes, some careers in the geospatial industry might seem obvious to you, while others will be a surprise. Some of these careers and applications likely fall within a discipline or area you already find interesting.

Visit the links below to see examples of GIScience being used in fields you might not have considered.

If you like...Video Games and Entertainment,

EA Sports Uses NASA Topographic Data in SSX Game

Link: How NASA topography brought dose of reality to SSX snowboarding courses [4] (ArsTechnica)

"He was like, 'Name any mountain on Earth,' and I was like, 'I don't know, Mount Everest.' So he goes on Wikipedia, gets the latitude and longitude coordinates... and in about 28 seconds, delivered a 3D model of Mount Everest and all the surrounding mountains in that grid from the data. He's like, 'If you give me a couple of days, we can take it for a ride...'"

If you like...Fisheries and Wildlife,

GIS and Remote Sensing are "Critical" to US Fish & Wildlife Service

Link: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service: Information Resources and Technology Management [6] | Critical Habitat Portal [7]

“Geospatial services provide the technology to create, analyze, maintain, and distribute geospatial data and information. GIS, GPS and remote sensing play a vital role in all of the Service’s long-term goals and in analyzing and quantifying the USFWS Operational Plan Measures.”

1.2 Data and Information

Whether it is a single geographic position of a movie-goer checking in at her favorite restaurant or the locations of thousands of animals equipped with GPS transmitters in a wildlife refuge, every GIS project and application is driven by data.

Data, generally, can be considered to be “values” of “variables”; the variables are the kind of phenomenon or its attributes that are measured, and the values can be numerical (e.g., the population of a city) or categorical (e.g., whether a highway is an Interstate or a U.S. route). When used in a computer system, these data must be in a form suitable for storage and processing. Data can represent all types of information and may consist of numbers, text, images, and many other formats. If you have an online profile, it probably asked you to enter a name, email address, photo, or phone number. These categories are data variables, and what you enter are the data values.

People create and study data as a means to help understand how natural and social systems work. Such systems can be hard to study because they're made up of many interacting phenomena that are often difficult to observe directly, and because they tend to change over time. We attempt to make systems and phenomena easier to study by measuring their characteristics at certain times. Because it's not practical to measure everything, everywhere, at all times, we measure selectively. How accurately data reflect the phenomena they represent depends on how, when, where, and what aspects of the phenomena were measured. It is important to keep in mind that all measurements contain a certain amount of error; the types of error, along with the concepts of accuracy and precision, will be discussed later. For now, however, we will focus on the characteristics of data and how data relate to information.

When phenomena are measured, one or more variables are recorded. As we have mentioned, recorded variables might consist of numerical values, names, or even pictures. All of these are referred to as variables, since they are only representations of the phenomena and may consist of several different values of the same type. Once collected, the variables can be treated as-is or combined and recalculated to form additional representations of the phenomena.

Encoding data in a form that can be reproduced on a computer facilitates storing these data components, sharing them with others, and adding them to structured collections, known as databases. Regardless of the type of data, computers follow instructions to convert data into various formats that are ultimately represented in binary form by series of ones and zeros, or bytes. Although the conversion of digital data to binary representations is beyond the scope of this course, it is important to remember one simple fact: if we can instruct computers to store digital data in this way, we can alter these instructions to make changes to the data. The ability to manipulate, combine, and process data is what allows us to turn a collection of measurements into information that can be used to answer specific questions.

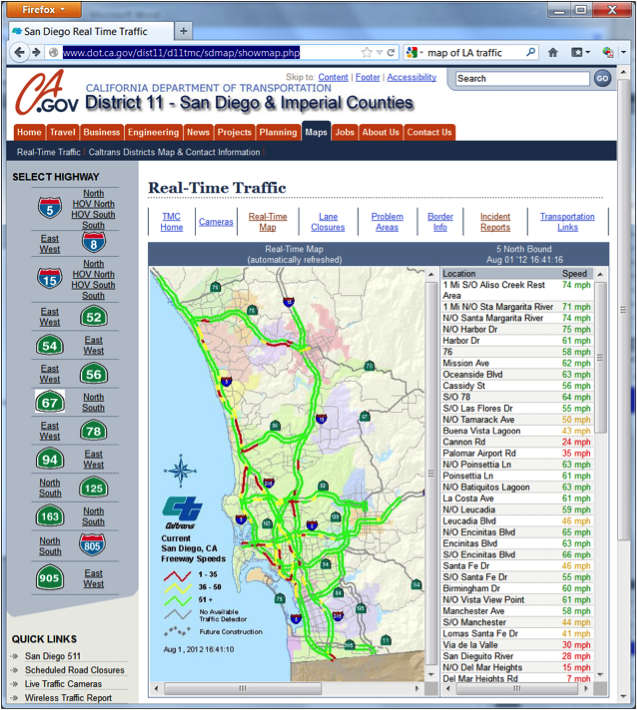

Information is data that has been selected or created in response to a question. For example, the location of a building or a route is data, until it is needed to dispatch an ambulance in response to an emergency. When used to inform those who need to know "where is the emergency, and what's the fastest route between here and there?," the data are transformed into information. The transformation involves the ability to ask the right kind of question, and the ability to retrieve existing data--or to generate new data from the old--that help people answer the question. The more complex the question, and the more locations involved, the harder it becomes to produce timely information. As a result, advancements in both computer software and hardware devices that can collect, integrate, and process large volumes of data quickly have become critical assets in the geospatial industry.

Geographic data and the information derived from it have become valuable commodities. Interestingly, in contrast to a commodity such as corn, the potential value of data is not lost when they are used. Data can be transformed into information again and again, provided that the data are kept up to date. Given the rapidly increasing accessibility of computers and communications networks in the U.S. and abroad, it is not surprising that data and information have become commodities, and that the ability to produce both has become a major growth industry.

When it comes to information, “spatial is special.” Reliance on spatial attributes is what separates geographic information from other types of information. Goodchild (1992) points out several distinguishing properties of geographic information. These properties are paraphrased below. Understanding them, and their implications for the practice of geographic information science, is a key objective of this course.

- Geographic data represent spatial locations and non-spatial attributes measured at certain times.

- Geographic space is continuous.

- Geographic space is nearly spherical.

- Geographic data tend to be spatially dependent.

The next section will clarify some of these properties and prepare you to understand the others as you progress through the course.

Practice Quiz

Registered Penn State students should return now take the self-assessment quiz about the Data and Information.

You may take practice quizzes as many times as you wish. They are not scored and do not affect your grade in any way.

1.3 Location, Attributes, and the First Law of Geography

When we generate information about phenomena that occur on or near the Earth’s surface, we do so using geographic data. Geographic data are data that include a reference to location on the Earth together with some non-spatial attributes. To be useful, they also need to include an indication of when the data refer to. The location specification is a key difference from other types of information that might only have an ID number or other descriptors, like the example in Table 1.1. When locational data are added (Table 1.2), these locations alone may be used to access the data, or one may combine location and non-spatial attributes to access data more specifically, such as when asking, “Which emergency vehicles of the type ‘ambulance’ are within 40 miles of my current location?”

| ID | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 42 | Patrol | Light-weight veh.. |

| 43 | Intercept | Performance crui.. |

| 44 | Ambulance | 2-axel diesel truc.. |

This is not geographic data. It does not have any locational data. Credit: Joshua Stevens, Department of Geography, The Pennsylvania State University.

The data in Table 1.1 above could not be used to answer the question posed. These data could only answer questions such as “which vehicle(s) is/are an ambulance?” (with an answer of ‘#44’) or “Are there any heavy-weight patrol cars in the fleet?” (with an answer of ‘no’). These data cannot answer any “where….?” question, because locations are not encoded.

By including coordinate information in the form of longitude and latitude, the data in Table 1.2 are geographic data. These spatial attributes can be used to identify the location of each item in the database, allowing us to ask questions of the type “where…?” and “how far…?”

| ID | Type | Description | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 42 | Patrol | Light-weight veh.. | 40.776853 | -77.87650 |

| 43 | Intercept | Performance crui.. | 34.594421 | -80.301819 |

| 44 | Ambulance | 2-axel diesel truc.. | 34.612899 | -79.635086 |

These geographic data have spatial attributes that can be used to link each entity to a place in the real world. (Locational Data highlighted in table above.) Credit: Joshua Stevens, Department of Geography, The Pennsylvania State University.

Later chapters will cover coordinates in more detail. The key point is that spatial attributes tell us where things are, or where things were at the time the data were collected. By simply including spatial attributes, geographic data allow us to ask a plethora of geographic questions. For example, we might ask “are gas prices in PA high?” The interactive map from GasBuddy.com [8] can help us with such a question while enabling us to generate many other spatial inquiries related to the geographic variation in fuel prices. Section 1.6 of this chapter will provide several more examples of these questions and the types of geographic data that can be used to answer them.

[8]

[8]

Another important characteristic of geographic space is that it is "continuous.” Although the Earth has valleys, canyons, caves, etc., there are no places on Earth without a location, and connections exist from one place to another. Outside of science fiction, there are no tears in the fabric of space-time. Modern technology can measure location very precisely, making it possible to generate extremely detailed depictions of geographic feature location (e.g., of the coastline of the eastern U.S). It is often possible to measure so precisely that we collect more location data than we can store and much more than is actually useful for practical applications. How much information is useful to store or to display in a map will depend on the map scale (how much of the world we represent within a fixed display such as the size of your computer screen) as well as on the map’s purpose.

Geographic data are generalized according to scale. Click on the buttons beneath the map to zoom in and out on the town of Gorham. (source: U.S. Geological Survey [9], public domain [10]).

For example, the illustration above shows a town called Gorham (in Maine) depicted on three different maps produced by the United States Geological Survey. Take note of the changes that occur when you select different scales (click the buttons below the map to change scale). The shape of the town along with the number and type of features included on the map are different at each scale. The cartographer has made generalization decisions to make sure that the information depicted is legible at each scale and to meet expected uses of maps produced at that scale.

As the map scale becomes larger (when you “zoom in”), the features become larger and more detailed. Switching to smaller scales (“zooming out”) reduces the number of features and simplifies their shapes. This feature reduction and simplification is an example of an important data processing operation called map generalization. Map generalization is a process that involves selecting which features of the world to represent (given what is possible with available data, which also will be selective) and multiple choices about the visible detail included in those representations. In the Gorham example, at the largest scale (1:24,000), all built structures in Gorham are depicted, while at 1:62,000, the built-up area is depicted abstractly as a pink polygon and you (as the map reader) are left to infer that towns include buildings. At the smallest scale (1:250,000), in addition to there being even fewer features depicted, many of the linear features have been smoothed out (e.g., highway 25 on the 1:250,000 map appears to have a slight, gentle curve as it cuts through town while its depiction on the 1:24,000 scale map shows that it has a distinct jog as well as an intersection that will appear to a driver as a U-turn).

In addition to being continuous, geographic data also tend to be spatially dependent. More simply, "everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things" (which leads to an expectation that things that are near to one another tend to be more alike than things that are far apart). The quote is the First Law of Geography, attributed to geographer Waldo Tobler (1970) -- University of California Department of Geography [11]. How alike things are in relation to their proximity to other things can be measured by a statistical calculation known as spatial autocorrelation. Without this fundamental property, geographic information science as we know it today would not be possible.

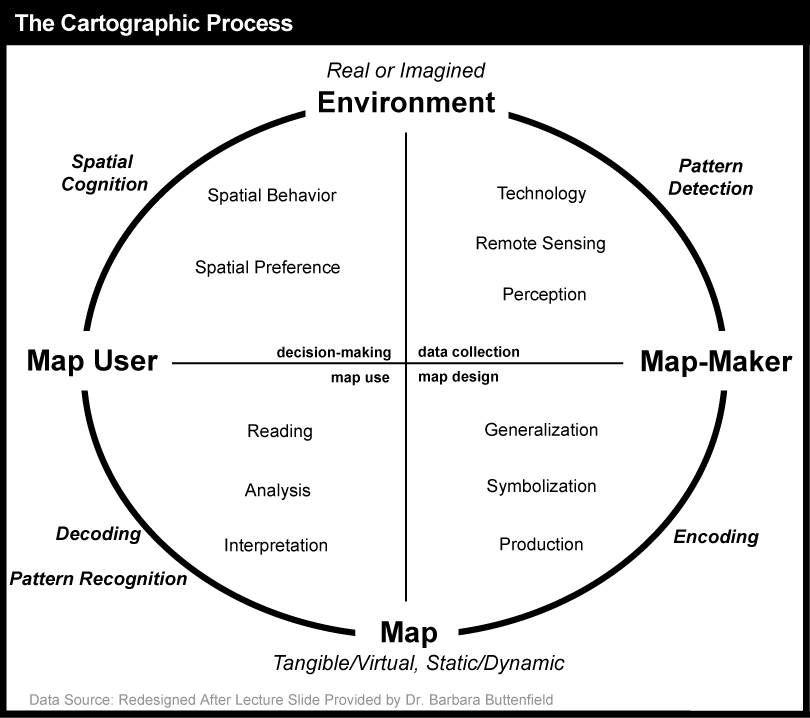

1.4 Communicating Geographic Data: What is a Map?

The table in Figure 1.2 of the previous section demonstrates one way to communicate geographic information. We can list data as a series of rows and columns and indicate locations with very specific coordinates. Despite being complete and efficient representations of data, text written in columns and rows is not very user friendly or easy for human beings to interpret. A visual representation would be much better.

The use of graphics and imagery as forms of communication predates written language by several thousand years. It is no surprise then that humans began to visually depict geographic information and have been doing so for millennia. Although the first graphic depiction of geographic information is debated (it is easy to imagine ephemeral maps drawn with sticks in the sand of a beach long before paper or even cave paintings), one of the earliest surviving representations to include both an indication of scale and orientation is the town plan of Nippur, created circa 1330 BC (O'Grady and O'Grady 2008 [12]); for a photo of this plan, see: Archaeology.org: Maps Exhibit review [13].

Try This: How would you define a map?

What is a map...exactly?

While there is a consensus that maps are extremely effective forms of communication, there are numerous definitions of what maps actually are and these definitions vary considerably. To understand why that is, let’s perform a simple exercise. Take a look at the images in Figure 1.5 below and decide which, if any, of them are maps.

It might surprise you, but with the right definition, each of the images above could qualify as a map. All of them rely on the spatial arrangement of information to communicate, and it is the spatial relationships between the elements in each image that provides meaning. Although they are not all geographic, the maps above introduce the idea of abstraction, or the process of representing phenomena or ideas with a simplified counterpart.

The idea of a map, with which you might be most familiar, is also an abstraction. Geographic maps are abstractions of the world we live in and phenomena on, within, or above its surface. As abstractions, maps allow features in the real world to be represented in paper, digital media, and databases, allowing us to calculate, present, and better understand the relationships that objects in the real world have with one another. In this course, you will learn about two primary types of maps: reference maps and thematic maps, defined more completely in Chapter 3.

As can be seen above, and in dictionary definitions, the term “map” is used well beyond geographic representations (e.g., Merriam-Webster definition [14]). Even when a geographic context is assumed, definitions include a wide range of representation forms. The International Cartographic Association has developed the following definition of geographic maps: “A map is a symbolised image of geographical reality, representing selected features or characteristics, resulting from the creative effort of its author’s execution of choices, and is designed for use when spatial relationships are of primary relevance.” This definition still allows tremendous variety. The definition is intentionally broad to include, for example, tactile maps for the visually impaired as shown below in Figure 1.4.

Practice Quiz

Registered Penn State students should return now take the self-assessment quiz About Maps.

You may take practice quizzes as many times as you wish. They are not scored and do not affect your grade in any way.

1.5 Sources of Geographic Data

Geographic data come in many types, from many different sources and captured using many techniques; they are collected, sold, and distributed by a wide array of public and private entities.

In general, we can divide the collection of geographic data into two main types:

- Directly collected data

- Remotely sensed data

Directly collected data are generated at the source of the phenomena being measured. Examples of directly collected data include measurements such as temperature readings at specific weather stations, elevations recorded by visiting the location of interest, or the position of a grizzly bear equipped with a GPS-enabled collar. Also included here are data derived through survey (e.g., the census) or observation (e.g., Audubon Christmas bird count).

Remotely sensed data are measured from remote distances without any direct contact with the phenomena or a need to visit the locations of interest (although directly collected “ground truth” data are often used to support accurate interpretation of the remotely sensed data; this is a topic we will pick up in Chapter 8). Satellite images, sonar readings, and radar are all forms of remotely sensed data.

For each type of data, there is a range of important issues about collection and processing that have an impact on how reliable and useful the data are. The federal agencies that collect and distribute geographic data and the standards by which they operate will be covered in Chapter 8.

1.6 Examples of Geographic Questions and Answers

So far, we have learned why geographic data are unique, how information differs from data, and how various forms of geographic information can be represented in computers and communicated to human beings. Let us now consider the types of questions we can ask, now that we are equipped with this knowledge.

The simplest geographic questions pertain to individual entities

Such questions include:

Questions about space

- Where is the entity located?

- What is its extent?

Questions about attributes

- What are the attributes of the entity located there?

- Do its attributes match one or more criteria?

Questions about time

- When were the entity's location, extent, or attributes measured?

- Has the entity's location, extent, or attributes changed over time?

Simple questions like these can be answered effectively with a good printed map, of course. However, GIS becomes increasingly attractive as the number of people asking the questions and the required level of precision grows, especially if they lack access to the required paper maps.

Questions concerning multiple geographic entities

- Do the entities contain one another?

- Do they overlap?

- Are they connected?

- Are they situated within a certain distance of one another?

- What is the best route from one entity to the others?

- Where are entities with similar attributes located?

Questions about attribute relationships

- Do the entities share attributes that match one or more criteria?

- Are the attributes of one entity influenced by changes in another entity?

Questions about temporal relationships

- Have the entities' locations, extents, or attributes changed over time?

Notice that all of these questions deal with where things are, how things relate to other things, and how things change or persist relative to these locations. These are the kinds of questions that GIScience and professionals in the geospatial industry are prepared to answer.

Practice Quiz

Registered Penn State students should return now take the self-assessment quiz about Geographic Questions and Properties.

You may take practice quizzes as many times as you wish. They are not scored and do not affect your grade in any way.

1.7 Glossary

Abstraction: A simplified representation of an idea, phenomenon, or concept.

Attribute: Data about geographic features are often found in geographic databases and are typically represented in the columns of the database. The spatial dimension is stored as an attribute of geographic data.

Data: Measured values of stored variables that reflect phenomena or characteristics about phenomena.

Directly Measured Data: Data that are measured at the physical location of the phenomena of interest.

Tobler's First Law of Geography: “All things are related, but near things are more alike than distant things.”

Generalization: The product or process of simplifying data or geographic representations.

Geographic Data: Recorded to represent spatial locations, that is a reference to a location on the Earth; often have associated attributes that are variables of locations across dimensions.

Geographic Information Science (GIScience): The theory, use, and application of geographic information systems and databases to answer spatial questions.

Information: Data that has been selected or created to answer a specific question.

Map Scale: The proportional difference between a distance on a map and a corresponding distance on the ground (Dm / Dg).

Remotely Sensed Data: Data collected from a distance without visiting or physically interacting with the phenomena of interest.

Variable: A property of data, that is, a record of a kind of phenomena.

1.8 Bibliography

Carstensen, L. W. (1986). Regional land information systems development using relational databases and geographic information systems. Proceedings of the AutoCarto, London, 507-516.

City of Ontario, California. (n.d.). Geographic information web server. Retrieved on July 6, 1999, from https://www.ontarioca.gov/information-technology [17] (since retired).

Cowen, D. J. (1988). GIS versus CAD versus DBMS: What are the differences? Photogrammetric Engineering and Remote Sensing 54:11, 1551-1555.

DiBiase, D. and twelve others (2010). The New Geospatial Technology Competency Model: Bringing workforce needs into focus [18]. URISA Journal 22:2, 55-72.

DiBiase, D, M. DeMers, A. Johnson, K. Kemp, A. Luck, B. Plewe, and E. Wentz (2007). Introducing the First Edition of the GIS&T Body of Knowledge [19]. Cartography and Geographic Information Science, 34(2), pp. 113-120. U.S. National Report to the International Cartographic Association.

Ennis, M. R. (2008). Competency models: A review of the literature and the role of the employment and training administration (ETA). http://www.careeronestop.org/COMPETENCYMODEL/info_documents/OPDRLiteratureReview.pdf [20].

GITA and AAG (2006). Defining and communicating geospatial industry workforce demand: Phase I report.

Goodchild, M. (1992). Geographical information science. International Journal of Geographic Information Systems 6:1, 31-45.

Goodchild, M. (1995). GIS and geographic research. In J. Pickles (Ed.), Ground truth: the social implications of geographic information systems (pp. of chapter). New York: Guilford.

National Decision Systems. A zip code can make your company lots of money! Retrieved on July 6, 1999, from http://laguna.natdecsys.com/lifequiz [21] (since retired).

National Geodetic Survey. (1997). Image generated from 15'x15' geoid undulations covering the planet Earth. Retrieved 1999, from https://geodesy.noaa.gov/web/science_edu/presentations_archive/ [22] (since retired).

Nyerges, T. L. & Golledge, R. G. (n.d.) NCGIA core curriculum in GIS, National Center for Geographic Information and Analysis, University of California, Santa Barbara, Unit 007. Retrieved November 12, 1997, from http://www.ncgia.ucsb.edu/ [23] (since retired).

O'Grady, J. V. and K. V. O'Grady (2008). The Information Design Handbook. Cincinnati, HOW Books.

Tobler, W.R. 1970: A computer movie simulating urban growth in the Detroit region. Economic Geography 46, 234-240.

United States Department of the Interior Geological Survey. (1977). [map]. 1:24 000. 7.5 minute series. Washington, D.C.: USDI.

United States Geologic Survey. "Bellefonte, PA Quadrangle" (1971). [map]. 1:24 000. 7.5 minute series. Washington, D.C.:USGS.

University Consortium for Geographic Information Science. Retrieved April 26, 2006, from http://www.ucgis.org [24]

Wilson, J. D. (2001). Attention data providers: A billion-dollar application awaits. GEOWorld, February, 54.

Worboys, M. F. (1995). GIS: A computing perspective. London: Taylor and Francis.

Chapter 2: Shrinking and Flattening the Globe: Scale, Projections, and Datums

Overview

Chapter 1 outlined several of the distinguishing properties of geographic information. One of these properties is that geographic maps are necessarily generalized, and that generalization tends to vary with scale. This chapter will introduce another distinguishing property related to the measurement and display of geographic information: that the Earth's complex, nearly-spherical but somewhat irregular shape complicates efforts to specify exact positions on the Earth's surface. In this chapter, we will explore the implications of these properties by illuminating concepts of scale, Earth geometry, coordinate systems, and the "horizontal datums" that define the relationship between coordinate systems and the Earth's shape.

Objectives

Compared to Chapter 1, Chapter 2 may seem long, technical, and abstract, particularly to those for whom these concepts are new. Chapter 2 will introduce some of the more technical concepts that are relevant to map construction and map reading. Students who successfully complete Chapter 2 will be able to:

- understand the concept of map scale and the multiple ways it is specified;

- demonstrate your ability to specify geographic locations using geographic coordinates;

- convert geographic coordinates between two different formats;

- explain the concept of a horizontal datum;

- recognize the kind of transformation that is appropriate to geo-register two or more data sets;

- describe the characteristics of the UTM coordinate system, including its basis in the Transverse Mercator map projection;

- describe the characteristics of the SPC system, including map projection on which it is based;

- interpret distortion diagrams to identify geometric properties of the sphere that are preserved by a particular map projection;

- classify projected map graticules by projection family.

Table of Contents:

- What is Scale?

- The Need for Coordinate Systems

- What are Map Projections?

- The Nearly Spherical Earth

- Glossary

- Biblography

Chapter lead adapter: Raechel Bianchetti.

Portions of this chapter were drawn directly from the following text:

Joshua Stevens, Jennifer M. Smith, and Raechel A. Bianchetti (2012), Mapping Our Changing World, Editors: Alan M. MacEachren and Donna J. Peuquet, University Park, PA: Department of Geography, The Pennsylvania State University.

2.1 What is Scale?

You hear the word "scale" often when you work around people who produce or use geographic information. If you listen closely, you will notice that the term has several different meanings, depending on the context in which it is used. You will hear talk about the scales of geographic phenomena and about the scales at which phenomena are represented on maps. You may even hear the word used as a verb, as in "scaling a map" or "downscaling." The goal of this section is for you to learn to tell these different meanings apart, and to be able to use concepts of scale to help make sense of geographic data.

2.1.1 Scope or Extent

Often "scale" is used as a synonym for "scope," or "extent." For example, the title of the article “Contractors Are Accused in Large-Scale Theft of Food Aid in Somalia,” [25] uses the term "large scale" to describe a widespread theft of food aid. This usage is common among the public. The term scale can also take on other meanings.

2.1.2 Measurement

The word "scale" can also be used as a synonym for a ruler--a measurement scale. Because data consist of symbols that represent measurements of phenomena, it is important to understand the reference systems used to take the measurements in the first place. In this section, we will consider a measurement scale known as the geographic coordinate system that is used to specify positions on the Earth's roughly spherical surface. In other sections, we will encounter two-dimensional (plane) coordinate systems, as well as the measurement scales used to specify attribute data.

2.1.3 Map Scale

Map scale is the proportion between a distance on a map and a corresponding distance on the ground (Dm / Dg). By convention, the proportion is expressed as a representative fraction in which map distance (Dm) is always reduced to 1. The representative fraction 1:100,000, for example, means that a section of road that measures 1 unit in length on a map stands for a section of road on the ground that is 100,000 units long. A representative fraction is unit-less, it has the same meaning if we are measuring on the map in inches, centimeters, or any other unit (in this example, the portion of the world represented on the map is 100,000 times as big as the map’s representation). If we were to change the scale of the map such that the length of the section of road on the map was reduced to, say, 0.1 units in length, we would have created a smaller-scale map whose representative fraction is 0.1:100,000, or 1:1,000,000.

2.1.4 Graphic Scales

Another way to express map scale is with a graphic (or "bar") scale (Figure 2.1). Unlike representative fractions, graphic scales remain true when maps are shrunk or magnified, thus they are especially useful on web maps where it is impossible to predict the size at which users will view them. Most maps include a bar scale like the one shown above left. Some also express map scale as a representative fraction. The implication in either case is that scale is uniform across the map. However, except for maps that show only very small areas, scale varies across every map. This follows from the fact that positions on the nearly spherical Earth must be transformed to positions on two-dimensional sheets of paper. Systematic transformations of the world (or parts of it) to flat maps are called map projections. As we will discuss in greater depth later in this chapter, all map projections are accompanied by deformation of features in some or all areas of the map. This deformation causes map scale to vary across the map. Representative fractions typically, therefore, specify map scale along a line at which deformation is minimal (nominal scale). We will discuss nominal scale in further detail later. Bar scales, also, generally denote only the nominal or average map scale. An alternative to a simple bar scale that accounts for map distortion is a variable scale. Variable scales, like the one illustrated above right, show how scale varies, in this case by latitude, due to deformation caused by map projection.

2.1.5 Changing a Map's Size

As noted above, another way that the term "scale" is used is as a verb. To ‘scale a map’ is to reproduce it at a different size. For instance, if you photographically reduce a 1:100,000-scale map to 50 percent of its original width and height, the result would be one-quarter the area of the original. Obviously, the map scale of the reduction would be smaller too: 1/2 x 1/100,000 = 1/200,000 (or a representative fraction scale specification of 1:200,000). Because of the inaccuracies inherent in all geographic data, scrupulous geographic information specialists avoid enlarging source maps. To do so is to exaggerate generalizations and errors.

In the following sections, you will learn more about the process of converting the three-dimensional Earth into a two-dimensional visual representation, the map. As you move through the chapter, keep in mind the different meanings for the term "scale" and think about how it relates to the process of map creation.

Practice Quiz

Registered Penn State students should return now take the self-assessment quiz about the Map Scale.

You may take practice quizzes as many times as you wish. They are not scored and do not affect your grade in any way.

2.2 The Need for Coordinate Systems

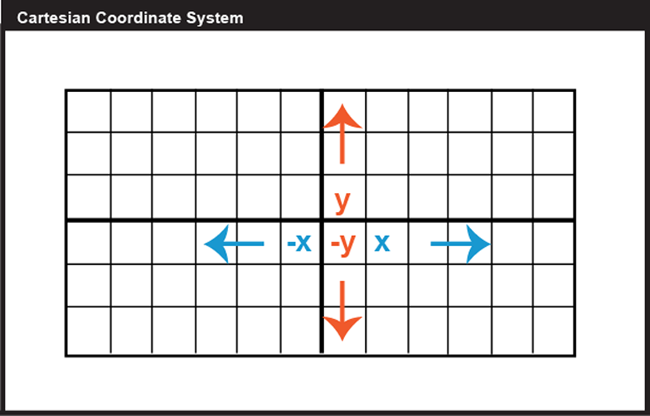

Locations on the Earth's surface are measured and represented in terms of coordinates; a coordinate is a set of two or more numbers that specifies the position of a point, line, or other geometric figure in relation to some reference system. The simplest system of this kind is a Cartesian coordinate system, named for the 17th century mathematician and philosopher René Descartes. A Cartesian coordinate system, like the one above in Figure 2.2, is simply a grid formed by put together two measurement scales, one horizontal (x) and one vertical (y). The point at which both x and y equal zero is called the origin of the coordinate system. In the illustration above, the origin (0,0) is located at the center of the grid (the intersection of the two bold lines). All other positions are specified relative to the origin. The coordinate of the upper right-hand corner of the grid is (6,3). The lower left-hand corner is (-6,-3).

Cartesian and other two-dimensional (plane) coordinate systems are handy due to their simplicity. They are not perfectly suited to specifying geographic positions. However, the geographic coordinate system, as seen in Figure 2.3, is designed specifically to define positions on the Earth's roughly spherical surface. Instead of the two linear measurement scales x and y, the geographic coordinate systems bring together two curved measurement scales.

You have probably encountered the terms latitude and longitude before in your studies. A comparison of these two scales is given below in Figure 2.4. The north-south scale, called latitude (designated by the Greek symbol phi), ranges from +90° (or 90° N) at the North pole to -90° (or 90° S) at the South pole while the equator is 0°. A line of latitude is also known as a parallel.

The east-west scale, called longitude (conventionally designated by the Greek symbol lambda), ranges from +180° to -180°. Because the Earth is round, +180° (or 180° E) and -180° (or 180° W) are the same grid line. A line of longitude is called a meridian. That +/- 180 grid line is roughly the International Date Line, which has diversions that pass around some territories and island groups so that they do not need to cope with the confusion of nearby places being in two different days. Opposite the International Date Line on the other side of the globe is the prime meridian, the line of longitude defined by international treaty as 0°. At higher latitudes, the length of parallels decreases to zero at 90° North and South. Lines of longitude are not parallel, but converge toward the poles. Thus, while a degree of longitude at the equator is equal to a distance of about 111 kilometers, that distance decreases to zero at the poles.

Try This: Geographic Coordinate System Practice Application

Have you ever encountered the terms ‘latitude’ or ‘longitude’? How well do you understand the geographic coordinate system, really? Our experience is that while everyone who enters this class has heard of latitude and longitude, only about half can point to the location on a map that is specified by a pair of geographic coordinates. The websites linked below let you test your knowledge. You’ll practice by clicking locations on a globe as specified by randomly generated geographic coordinates.

Map Quiz Game [27]

2.2.1 Geographic Coordinates

We have discussed the fact that both latitude and longitude are measured in degrees, but what about when we need a finer granularity measurement? To record geographic coordinates, we can further divide degrees into minutes, and seconds. The degree is equal to sixty minutes, and each minute equal to sixty seconds. Geographic coordinates often need to be converted in order to geo-register one data layer onto another. Geographic coordinates may be expressed in decimal degrees, or in degrees, minutes, and seconds. Sometimes, you need to convert from one form to another.

Here's how it works:

To convert Latitude of -89.40062 from decimal degrees to degrees, minutes, seconds:

Subtract the number of whole degrees (89°) from the total (89.40062°). (The minus sign is used in the decimal degree format only to indicate that the value is a west longitude or a south latitude.) In this example, the minus sign indicates South, so keep track of that.

Multiply the remainder by 60 minutes (.40062 x 60 = 24.0372).

Subtract the number of whole minutes (24') from the product.

Multiply the remainder by 60 seconds (.0372 x 60 = 2.232). Round off (to the nearest second in this case).

Assemble the pieces; the result is 89° 24' 2" S. If the starting point had been the Longitude of -89.400062, the only difference would be that the S above would be replaced by a W.

To convert 43° 4' 31" from degrees, minutes, seconds to decimal degrees, use the simple formula below:

DD = Degrees + (Minutes/60) + (Seconds/3600)

Divide the number of seconds by 60 (31 ÷ 60 = 0.5166).

Add the quotient of step (1) to the whole number of minutes (4 + 0.5166).

Divide the result of step (2) by 60 (4.5166 ÷ 60 = 0.0753).

Add the quotient of step (3) to the number of whole number degrees (43 + 0.0753).

The result is 43.0753°

Practice Quiz

Registered Penn State students should return now take the self-assessment quiz about Geographic Coordinates.

You may take practice quizzes as many times as you wish. They are not scored and do not affect your grade in any way.

2.2.2 Plane Coordinates

So far, you have read about Cartesian Coordinate Systems, but that is not the only kind of 2D coordinate system. A plane coordinate system can be thought of as the juxtaposition of any two measurement scales. In other words, if you were to place two rulers at right angles, such that the "0" marks of the rulers aligned, you would define a plane coordinate system. The rulers are called "axes." Just as in Cartesian Coordinates, the absolute location of any point in the space in the plane coordinate system is defined in terms of distance measurements along the x (east-west) and y (north-south) axes. A position defined by the coordinates (1,1) is located one unit to the right, and one unit up from the origin (0,0). The Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) grid is a widely-used type of geographic plane coordinate system in which positions are specified as eastings (distances, in meters, east of an origin) and northings (distances north of the origin).

Some coordinate transformations are simple. The transformation from non-georeferenced plane coordinates to non-georeferenced polar coordinates, described in further detail later in the chapter, shown below involves nothing more than the replacement of one kind of coordinates with another.

2.2.3 UTM: Universal Transverse Mercator

The geographic coordinate system grid of latitudes and longitudes consists of two curved measurement scales to fit the nearly-spherical shape of the Earth. As discussed above, geographic coordinates can be specified in degrees, minutes, and seconds of arc. Curved grids are inconvenient to use for plotting positions on flat maps. Furthermore, calculating distances, directions, and areas with spherical coordinates is cumbersome in comparison to doing so with plane coordinates. For these reasons, cartographers and military officials in Europe and the U.S. developed the UTM coordinate system. UTM grids are now standard not only on printed topographic maps but also for the geographic referencing of the digital data that comprise the emerging U.S. "National Map" (NationalMap.gov [30]).

"Transverse Mercator" refers to the manner in which geographic coordinates are transformed from a spherical model of the Earth into plane coordinates. The act of mathematically transforming geographic spherical coordinates to plane coordinates necessarily displaces most (but not all) of the transformed coordinates to some extent. Because of this, map scale varies within projected (plane) UTM coordinate system grids. Thus, UTM coordinates provide locations specifications that are precise, but have known amounts of positional error depending on where the place is.

Shown below is the southwest corner of a 1:24,000-scale (for which 1 inch on the map represents 2000 ft. in the world) State College topographic map in Centre County, PA, published by the United States Geological Survey (USGS). Note that the geographic coordinates (40° 45' N latitude, 77° 52' 30" W longitude) of the corner are specified. Also shown, however, are ticks and labels representing two plane coordinate systems, the Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) system and the State Plane Coordinates (SPC) system. The tick on the west edge of the map labeled "4515" represents a UTM grid line (called a "northing") that runs parallel to, and 4,515,000 meters north of, the equator. Ticks labeled "258" and "259" represent grid lines that run perpendicular to the equator and 258,000 meters and 259,000 meters east, respectively, of the origin of the UTM Zone 18 North grid (see its location on Fig 6 above). Unlike longitude lines, UTM "eastings" are straight and do not converge upon the Earth's poles.

The Universal Transverse Mercator system is not really universal, but it does cover nearly the entire Earth surface. Only polar areas--latitudes higher than 84° North and 80° South--are excluded. (Polar coordinate systems are used to specify positions beyond these latitudes.) The UTM system divides the remainder of the Earth's surface into 60 zones, each spanning 6° of longitude. These are numbered west to east from 1 to 60, starting at 180° West longitude (roughly coincident with the International Date Line).

The illustration above depicts UTM zones as if they were uniformly "wide" from the Equator to their northern and southern limits. In fact, since meridians converge toward the poles on the globe, every UTM zone tapers from 666,000 meters in "width" at the Equator (where 1° of longitude is about 111 kilometers in length) to only about 70,000 meters at 84° North and about 116,000 meters at 80° South.

To clarify this, the illustration below depicts the area covered by a single UTM coordinate system grid zone. Each UTM zone spans 6° of longitude, from 84° North to 80° South. Each UTM zone is subdivided along the equator into two halves, north and south.

The illustration above shows how UTM coordinate grids relate to the area of coverage illustrated above. The north and south halves are shown side by side for comparison. Each half is assigned its own origin. The north south zone origins are positioned to south and west of the zone. North zone origins are positioned on the Equator, 500,000 meters west of the central meridian for that zone. Origins are positioned so that every coordinate value within every zone is a positive number. This minimizes the chance of errors in distance and area calculations. By definition, both origins are located 500,000 meters west of the central meridian of the zone (in other words, the easting of the central meridian is always 500,000 meters E). These are considered "false" origins since they are located outside the zones to which they refer. UTM eastings specifying places within the zone range from 167,000 meters to 833,000 meters at the equator. These ranges narrow toward the poles. Northings range from 0 meters to nearly 9,400,000 in North zones and from just over 1,000,000 meters to 10,000,000 meters in South zones. Note that positions at latitudes higher than 84° North and 80° South are defined in Polar Stereographic coordinate systems that supplement the UTM system.

The distorted ellipse graph below shows the amount of distortion on a UTM map. This kind of plot will be explained in more detail below; the key thing to note here is that the size and shape of features plotted in red indicate the amount of size and shape distortion across the map (a wide range in sizes indicates substantial area distortion, a range from circles to flat ellipses indicates substantial shape distortion). The ellipses centered within the highlighted UTM zone are all the same size and shape. Away from the highlighted zone, the ellipses steadily increase in size, although their shapes remain uniformly circular. This pattern indicates that scale distortion is minimal within Zone 30, and that map scale increases away from that zone. Furthermore, the ellipses reveal that the character of distortion associated with this projection is that shapes of features as they appear on a globe are preserved while their relative sizes are distorted. Map projections that preserve shape by sacrificing the fidelity of sizes are called conformal projections. The plane coordinate systems used most widely in the U.S., UTM and SPC (the State Plane Coordinates system), are both based upon conformal projections.

The Transverse Mercator projection illustrated above minimizes distortion within UTM zone 30 by putting that zone at the center of the projection. Fifty-nine variations on this projection are used to minimize distortion in the other 59 UTM zones. In every case, distortion is no greater than 1 part in 1,000. This means that a 1,000 meter distance measured anywhere within a UTM zone will be no worse than + or - 1 meter off.

One disadvantage of the UTM system is that multiple coordinate systems must be used to account for large entities. The lower 48 United States, for instance, spreads across ten UTM zones. The fact that there are many narrow UTM zones can lead to confusion. For example, the city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania is east of the city of Pittsburgh. If you compare the Eastings of centroids representing the two cities, however, Philadelphia's Easting (about 486,000 meters) is less than Pittsburgh's (about 586,000 meters). Why? Because although the cities are both located in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania, they are situated in two different UTM zones. As it happens, Philadelphia is closer to the origin of its Zone 18 than Pittsburgh is to the origin of its Zone 17. If you were to plot the points representing the two cities on a map, ignoring the fact that the two zones are two distinct coordinate systems, Philadelphia would appear to the west of Pittsburgh. Inexperienced GIS users make this mistake all the time. Fortunately, GIS software is getting sophisticated enough to recognize and merge different coordinate systems automatically.

Practice Quiz

Registered Penn State students should return now take the self-assessment quiz about the UTM Coordinates.

You may take practice quizzes as many times as you wish. They are not scored and do not affect your grade in any way.

2.2.4 State Plane Coordinates

The UTM system was designed to meet the need for plane coordinates to specify geographic locations globally. Focusing on just the U.S., in consultation with various state agencies, the U.S. National Geodetic Survey (NGS) devised the State Plane Coordinate System with several design objectives in mind. Chief among these were:

- plane coordinates for ease of use in calculations of distances and areas;

- all positive values to minimize calculation errors; and

- a maximum error rate of 1 part in 10,000.

As discussed above, plane coordinates specify positions in flat grids. Map projections are needed to transform latitude and longitude coordinates to plane coordinates. The designers of the SPCS did two things to minimize the inevitable distortion associated with projecting the Earth onto a flat surface. First, they divided the U.S. into 124 relatively small zones that cover the 50 U.S. states. Second, they used slightly different map projection formulae for each zone, one that minimizes distortion along either the east-west or north-south line depending on the orientation of the zone. The curved, dashed red lines in the illustration below represent the two standard lines that pass through each zone. Standard lines indicate where a map projection has zero area or shape distortion (some projections have only one standard line).

As shown below, some states are covered with a single zone while others are divided into multiple zones. Each zone is based upon a unique map projection that minimizes distortion in that zone to 1 part in 10,000 or better. In other words, a distance measurement of 10,000 meters will be at worst one meter off (not including instrument error, human error, etc.). The error rate varies across each zone, from zero along the projection's standard lines to the maximum at points farthest from the standard lines. Errors will be much lower than the maximum at most locations within a given SPC zone. SPC zones achieve better accuracy than UTM zones because they cover smaller areas, and so are less susceptible to projection-related distortion.

As we have seen above, positions in any coordinate system are specified relative to an origin. Like UTM zones, SPC zone origins are defined so as to ensure that every easting and northing in every zone are positive numbers. As shown in the illustration below, SPC origins are positioned south of the counties included in each zone. The origins coincide with the central meridian of the map projection upon which each zone is based. The false origin of the Pennsylvania North zone, is defined as 600,000 meters East, 0 meters North. Origin eastings vary from zone to zone from 200,000 to 8,000,000 meters East.

The SPCS zones are identified with a 4 digita FIPS code, the first two digits represents the state and the second the zone (e.g., PA has a FIPS code of 37 with 2 zones, 1 and 2, thus 3701 for the nothern zone and 3702 for the sourthern). The starting "0" for states in the 1-9 range is typically dropped; thus for CA, as an example, the most norther SPCS zone is 401.

One place you can look up all zone numbers is here: USA State Plane Zones NAD83 [32]

Shown below is the southwest corner of the same 1:24,000-scale topographic map used as an example above. Along with the geographic coordinates (40 45' N latitude, 77° 52' 30" W longitude) of the corner and UTM tick marks discussed above, SPCS eastings and northings are also included. The tick labeled "1 970 000 FEET" represents a SPC grid line that runs perpendicular to the equator and 1,970,000 feet east of the origin of the Pennsylvania North zone. Notice that, in this example, SPC system coordinates are specified in feet rather than meters. The SPC system switched to use of meters in 1983, but most existing topographic maps are older than that and still give the specification in feet (as in the example below). The origin lies far to the west of this map sheet. Other SPC grid lines, called "northings" (the one for 220,000 FEET is shown), run parallel to the equator and perpendicular to SPC eastings at increments of 10,000 feet. Unlike longitude lines, SPC eastings and northings are straight and do not converge upon the Earth's poles.

SPCs, like all plane coordinate systems, pretend the world is flat. The basic design problem that confronted the geodesists who designed the State Plane Coordinate System was to establish coordinate system zones that were small enough to minimize distortion to an acceptable level, but large enough to be useful.

Most SPC zones are based on either a Transverse Mercator or Lambert Conic Conformal map projection whose parameters (such as standard line(s) and central meridians) are optimized for each particular zone. "Tall" zones like those in New York state, Illinois, and Idaho are based upon unique Transverse Mercator projections that minimize distortion by running two standard lines north-south on either side of the central meridian of each zone, much as the same projection is used for UTM zones. "Wide" zones like those in Pennsylvania, Kansas, and California are based on unique Lambert Conformal Conic projections (see below for more on this and other projections) that run two standard lines (standard parallels, in this case) west-east through each zone. (One of Alaska's zones is based upon an "oblique" variant of the Mercator projection. That means that instead of standard lines parallel to a central meridian, as in the transverse case, the Oblique Mercator runs two standard lines that are tilted so as to minimize distortion along the Alaskan panhandle.)

These two types of map projections share the property of conformality, which means that angles plotted in the coordinate system are equal to angles measured on the surface of the Earth. As you can imagine, conformality is a useful property for land surveyors, who make their livings measuring angles.

This section has hinted at some of the characteristics of map projections and how they are used to relate plane coordinates to the globe. Next, we delve more deeply into the topic of map projections, a topic that has fascinated many mathematicians and others over centuries.

Practice Quiz

Registered Penn State students should return now take the self-assessment quiz about the State Plane Coordinates.

You may take practice quizzes as many times as you wish. They are not scored and do not affect your grade in any way.

2.3 What are Map Projections?

Latitude and longitude coordinates specify positions in a spherical grid called the graticule (that approximates the more-or-less spherical Earth). The true geographic coordinates called unprojected coordinate in contrast to plane coordinates, like the Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) and State Plane Coordinates (SPC) systems, that denote positions in flattened grids. These georeferenced plane coordinates are referred to as projected. The mathematical equations used to project latitude and longitude coordinates to plane coordinates are called map projections. Inverse projection formulae transform plane coordinates to geographic. The simplest kind of projection, illustrated below, transforms the graticule into a rectangular grid in which all grid lines are straight, intersect at right angles, and are equally spaced. Projections that are more complex yield grids in which the lengths, shapes, and spacing of the grid lines vary. Even this simplest projection produces various kinds of distortions; thus, it is necessary to have multiple types of projections to avoid specific types of distortions. Imagine the kinds of distortion that would be needed if you sliced open a soccer ball and tried to force it to be completely flat and rectangular with no overlapping sections. That is the amount of distortion we have in the simple projection below (one of the more common in web maps of the world today).

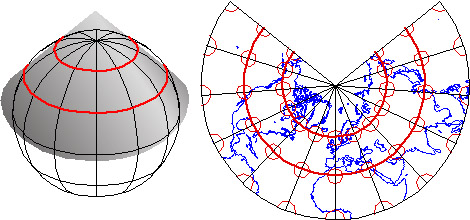

Many types of map projections have been devised to suit particular purposes. The term "projection" implies that the ball-shaped net of parallels and meridians is transformed by casting its shadow upon some flat, or flattenable, surface. While almost all map projection methods are created using mathematical equations, the analogy of an optical projection onto a flattenable surface is useful as a means to classify the bewildering variety of projection equations devised over the past two thousand years or more.

There are three main categories of map projection, those in which projection is directly onto a flat plane, those onto a cone sitting on the sphere that can be unwrapped, and other onto a cylinder around the sphere that can be unrolled (Figure 2.15 above). All three are shown in their normal aspects. The plane often is centered upon a pole. The cone is typically aligned with the globe such that its line of contact (tangency) coincides with a parallel in the mid-latitudes. Moreover, the cylinder is frequently positioned tangent to the equator (unless it is rotated 90°, as it is in the Transverse Mercator projection). As you might imagine, the appearance of the projected grid will change quite a lot depending on the type of surface it is projected onto, how that surface is aligned with the globe, and where that imagined light is held. The following illustrations show some of the projected graticules produced by projection equations in each category.

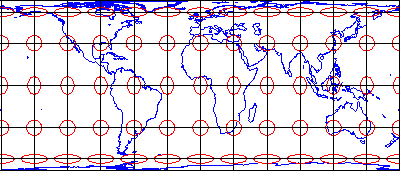

- Cylindric projection equations yield projected graticules with straight meridians and parallels that intersect at right angles. The example shown above is a Cylindrical Equidistant (also called Plate Carrée or geographic) in its normal equatorial aspect.

- Pseudocylindric projections are variants on cylindrics in which meridians are curved. The result of a Sinusoidal projection is shown above.

- Conic projections yield straight meridians that converge toward a single point at the poles, parallels that form concentric arcs. The example shown above is the result of an Albers Conic Equal Area, which is frequently used for thematic mapping of mid-latitude regions.

- Planar projections also yield meridians that are straight and convergent, but parallels form concentric circles rather than arcs. Planar projections are also called azimuthal because every planar projection preserves the property of azimuthality, directions (azimuths) from one or two points to all other points on the map. The projected graticule shown above is the result of an Azimuthal Equidistant projection in its normal polar aspect.

Appearances can be deceiving. It is important to remember that the look of a projected graticule depends on several projection parameters, including latitude of projection origin, central meridian, standard line(s), and others. Customized map projections may look entirely different from the archetypes described above (Figure 2.16).

To help interpret the wide variety of projections, it is necessary to become familiar with Spatial Reference Information that traditionally accompanies a map. There are several terms that you must understand to read the Spatial Reference Information. First, the projection name identifies which projection was used. With this information, you get an understanding of the projection category and the geometric properties the projection preserves. Next, the central meridian is the location of the central longitude meridian. The Latitude of Projection defines the origin of latitude for the projection. There are three common aspects that we can define: polar (projections centered on a pole), equatorial (usually cylindrical or pseudo-cylindrical projections aligned with the equator), and oblique (those centered on any other place). Scale Factor at Central Meridian is the ratio of map scale along the central meridian and the scale at a standard meridian, where scale distortion is zero. Finally, some projections, including the Lambert Conic Conformal, include parameters by which you can specify one or two standard lines along which there is no scale distortion.

2.3.1 Map Projections: Distortion

No projection allows us to flatten the globe without distorting it. Distortion ellipses help us to visualize what type of distortion a map projection has caused, how much distortion occurred, and where it occurred. The ellipses show how imaginary circles on the globe are deformed because of a particular projection. If no distortion had occurred in the process of projecting the map shown below, all of the ellipses would be the same size, and circular in shape.

When positions on the graticule are transformed to positions on a projected grid, four types of distortion can occur: distortion of sizes, angles, distances, and directions. Map projections that avoid one or more of these types of distortion are said to preserve certain properties of the globe: equivalence, conformality, equidistance, and azimuthality, respectively. Each is described below.

2.3.1.1 Equivalence

So-called equal-area projections maintain correct proportions in the sizes of areas on the globe and corresponding areas on the projected grid (allowing for differences in scale, of course). Notice that the shapes of the ellipses in the Cylindrical Equal Area projection above are distorted, but the areas each one occupies are equivalent. Equal-area projections are preferred for small-scale thematic mapping (discussed in the next chapter), especially when map viewers are expected to compare sizes of area features like countries and continents.

2.3.1.2 Conformality

The distortion ellipses plotted on the conformal projection shown above vary substantially in size, but are all the same circular shape. The consistent shapes indicate that conformal projections preserve the fidelity of angle measurements from the globe to the plane. In other words, an angle measured by a land surveyor anywhere on the Earth's surface can be plotted at its corresponding location on a conformal projection without distortion. This useful property accounts for the fact that conformal projections are almost always used as the basis for large scale surveying and mapping. Among the most widely used conformal projections are the Transverse Mercator, Lambert Conformal Conic, and Polar Stereographic.

Conformality and equivalence are mutually exclusive properties. Whereas equal-area projections distort shapes while preserving fidelity of sizes, conformal projections distort sizes in the process of preserving shapes.

As discussed above in section 2.2.4, SPC zones that trend west to east (including Pennsylvania's) are based on unique Lambert Conformal Conic projections. Instead of the cylindrical projection surface used by projections like the Mercator shown above, the Lambert Conformal Conic and map projections like it employ conical projection surfaces like the one shown below. Notice the two lines at which the globe and the cone intersect. Both of these are standard lines; specifically, standard parallels. The latitudes of the standard parallels selected for each SPC zones minimize scale distortion throughout that zone.

2.3.1.3 Equidistance

Equidistant map projections allow distances to be measured accurately along straight lines radiating from one or, at most, two points or they can have correct distance (thus maintain scale) along one or more lines. In the example below (also sometimes called an "equirectangular" projection because the parallels and meridians are both equally spaced). Notice that ellipses plotted on the Cylindrical Equidistant (Plate Carrée) projection shown above vary in both shape and size. The north-south axis of every ellipse is the same length, however. This shows that distances are true-to-scale along every meridian; in other words, the property of equidistance on this map projection is preserved from the two poles.

2.3.1.4 Azimuthality

Azimuthal projections preserve directions (azimuths) from one or two points to all other points on the map. Gnomonic projections, like the one above, display all great circles as straight lines. A great circle is the most direct path between two locations across the surface of the globe. See how the ellipses plotted on the gnomonic projection shown above vary in both size and shape, but are all oriented toward the center of the projection. In this example, that is the one point at which directions measured on the globe are not distorted on the projected graticule. This is a good projection for uses like plotting airline connections from one airport to all others.

2.3.1.5 Compromise

Some map projections preserve none of the properties described above, but instead seek a compromise that minimizes distortion of all kinds. The example shown above is the Polyconic projection, where parallels are all non-concentric circular arcs, except for a straight equator, and the centers of these circles lie along a central axis. The U.S. Geological Survey used the polyconic projection for many years as the basis of its topographic quadrangle map series until the conformal Transverse Mercator succeeded it. Another example is the Robinson projection, which is often used for small-scale thematic maps of the world (it was used as the primary world map projection by the National Geographic Society from 1988-1997, then replaced with another compromise projection, the Winkel Tripel; thus, the latter has become common in textbooks).

Try This: Album of Map Projections

John Snyder and Phil Voxland (1994) published an Album of Map Projections that describes and illustrates many more examples in each projection category. Excerpts from that important work are included in our Interactive Album of Map Projections, which registered students will use to complete Project 1. The Interactive Album is available at the PSU Interactive Album of Map Projections [33].Flex Projector is a free, open source software program developed in Java that supports many more projections and variable parameters than the Interactive Album. Bernhard Jenny of the Institute of Cartography at ETH Zurich created the program with assistance from Tom Patterson of the US National Park Service. You can download Flex Projector from FlexProjector.com [34]

Those who wish to explore map projections in greater depth than is possible in this course might wish to visit an informative page published by the International Institute for Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation (Netherlands), which is known by the legacy acronym ITC. The page is available at Kartoweb Map Projections. [35]

Practice Quiz

Registered Penn State students should return now take the self-assessment quiz about the Map Projections.

You may take practice quizzes as many times as you wish. They are not scored and do not affect your grade in any way.

2.4 The Nearly Spherical Earth

You know that the Earth is not flat; but, as we have implied already, it is not spherical either! For many purposes, we can ignore the variation from a sphere; but, if accuracy matters, the Earth is best described as a geoid. A geoid is the equipotential surface of the Earth's gravity field; put simply, it has the shape of a lumpy, slightly squashed ball. Determining the precise shape of the geoid is a major concern of the science of geodesy, the study of Earth’s size, shape, and gravitational and magnetic fields. The accuracy of coordinates that specify geographic locations depends upon how the coordinate system grid is aligned with the Earth's surface, and that alignment depends on the model we use to represent the actual shape of the geoid. While geodesy is an old science, many challenging problems remain, and geodesists continue to make advances that increase our ability to locate places accurately (and that gradually make the location of the GPS in your phone more accurate).

Geoids are lumpy because gravity varies from place to place in response to local differences in terrain and variations in the density of materials in the Earth's interior. The Earth’s geoid is also a little squat, as suggested above. Sea level gravity at the poles is greater than sea level gravity at the equator, a consequence of Earth's "oblate" shape as well as the centrifugal force associated with its rotation.

Geodesists at the U.S. National Geodetic Survey (NGS Geoid 12A [36]) describe the geoid as an "equipotential surface" because the potential energy associated with the Earth's gravitational pull is equivalent everywhere on the surface. The geoid is essentially a three-dimensional mathematical surface that fits (as closely as possible) gravity measurements taken at millions of locations around the world. As additional, and more accurate, gravity measurements become available, geodesists revise the shape of the geoid periodically. Some geoid models are solved only for limited areas; GEOID03, for instance, is calculated only for the continental U.S.

It is important to differentiate the bumpiness of a geoid from the ruggedness of Earth’s terrain, since geoids depend on gravitational measurements and are not simply representations of Earth’s topographic features. Although Earth’s topography, which consists of extreme heights like Mount Everest (29,029 ft above sea level) and incredible depths like the Mariana Trench (36,069 ft below sea level), the Earth’s average terrain is relatively smooth. Astronomer Neil de Grasse Tyson (2009) points out: "Earth, as a cosmic object is remarkably smooth; if you had a giant finger and rubbed it across Earth's surface (oceans and all), Earth would feel as smooth as a cue ball. Expensive globes that portray raised portions of Earth’s landmasses to indicate mountain ranges depict a grossly exaggerated reality (p. 39)."

2.4.1 Ellipsoid

An ellipsoid is a three-dimensional geometric figure that resembles a sphere, but whose equatorial axis (a in the Figure 2.23 above) is slightly longer than its polar axis (b). Ellipsoids are commonly used as surrogates for geoids to simplify the mathematics involved in relating a coordinate system grid with a model of the Earth's shape. Ellipsoids are good, but not perfect, approximations of geoids; they more closely model the actual shape of the Earth than a simple sphere. One implication of different models of the Earth is that they represent elevation of places as different. Surveyors and engineers measure elevations at construction sites and elsewhere. Elevations are expressed in relation to a vertical datum, a reference surface such as mean sea level. Different geoids and different ellipsoids define the vertical datum differently. The map below (Figure 2.24) shows differences in elevation between the GEOID96 geoid model and the WGS84 ellipsoid. The surface of GEOID96 represents the surface as being 75 meters higher than does the WGS84 ellipsoid over New Guinea (where the map is colored red). In the Indian Ocean (where the map is colored purple), the surface of GEOID96 represents the surface as about 104 meters below the ellipsoid surface.

Many ellipsoids are in use around the world. Local ellipsoids minimize differences between the geoid and the ellipsoid for individual countries or continents. The Clarke 1866 ellipsoid, for example, minimizes deviations in North America.

Once we have identified a preferable shape with which to represent the Earth (the specific ellipsoid), the next consideration that we must make is the coordinate system to provide a means to define positions of locations on that sphere (spherical coordinate system).

2.4.2 Horizontal Datums

Horizontal datum is an elusive concept for many GIS practitioners. However, it is relatively easy to understand if we start with the concept that the datum defines the position of a coordinate system in relation to the places being located. Before considering horizontal datums in the context of geographic (spherical) coordinates, consider the simple example below that uses plane coordinates. In this example, the “datum” is a simple Cartesian grid. The figure shows what would happen if the horizontal datum of any plane coordinate system had a different origin from which all coordinates were determined (e.g., if the false origin of any SPCS zone was a slightly different place.