Section 4: Food Systems and Sustainability

Section 4: Food Systems and Sustainability

Overview

Modules

- Module 10: Food Systems

- Module 11: Human-Environment Interactions

- Capstone Stage 4

- Module 12: Capstone Stage 5

Section Goals

Upon completion of Section 4 students will be able to:

- Describe ways that food systems impact the earth system.

- Explain the characteristics and scale of the three major food systems coexisting in the world today and their overlap.

- Demonstrate the complexity and interconnectedness of food system types that connecting society to the environment in different ways within a globalized world.

- Construct an assessment that measures the impacts of food systems on the earth system and local environments.

- Describe the concepts of resilience, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability (RACV) in a food system.

- Explain food access and food insecurity as a key challenge to food systems.

- Appraise the value of human seed systems and agrobiodiversity as human system components that incorporate crops as natural components and foster resilience.

- Apply concepts of RACV to understand changes in seed systems and food production in examples.

- Analyze stresses and shocks from climate change and food system failure that lead to both gradual changes in food systems and acute crises such as famines.

Section Learning Objectives

In order to reach these goals, we have established the following learning objectives for student learning. Upon completion of the modules within Section 4, you will be able to:

- Define food systems and name the component systems, the roles played by each, and the three dominant and overlapping types of food systems in the world today.

- Name different types of impacts of the food system on earth’s natural systems.

- Define the basic elements of a coupled human-natural system.

- Describe a life cycle assessment (LCA) and state what it is used for.

- Explain examples of food systems to illustrate and compare the combined social and environmental inputs and impacts.

- Apply the concept of natural human systems to food systems and distinguish different ways that food systems develop and change because of human and natural factors.

- Apply a coupled natural system framework to describe how human systems affect earth’s natural systems within food systems.

- Construct life-cycle assessments using data on food production activities that compare the impacts of different types of food systems on the earth systems.

- Synthesize outputs of LCAs you have constructed to compare impacts of different food production systems.

- Define the concepts of perturbations and shocks, resilience, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability in the context of agri-food systems.

- Define and describe agrobiodiversity within food production systems and changes in this agrobiodiversity over time

- Define the concepts of food access, food security, food Insecurity, malnutrition, and famine.

- Give examples of resilience, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability in food systems.

- Give examples of support systems for biodiversity in land use and food systems

- Use an online mapping resource to compare different parts of the United States in terms of food access, and identify key areas with low food access.

- Evaluate recent examples in land use and food systems of resilience, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability (RACV).

- Analyze an example of a recent famine and understand how multiple factors of vulnerability and shocks combine to create widespread conditions of food insecurity known as famines.

- Propose actions that can be taken to respond to and prevent famine within a recent historical example.

- Propose principles embodying RACV for incorporation into a proposal/scenario for an example food system (capstone project)

Module 10: Food Systems

Module 10: Food Systems

Overview

Understanding Coupling in Natural and Human Systems

Module 10 continues the theme of human-environment interactions seen at smaller scales in agroecosystems in module 8 and elaborates on the coupled human-natural systems (CHNS) concept introduced in Module 1. As learners, in Module 10.1 you will explore different scales and types of food systems, learn about barriers food producers face within food systems, and look in detail at how the framework of CHNS allows us to see divergences of food system into different types, and transitions from one type to another. In Module 10.2 you’ll learn about the impacts of food systems on natural systems, and practice a method called Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA) which is used to measure the impact of Human Food System components on the environment. LCAs can be applied to measure the impacts of both particular products as well as complex human systems on the environment. The food systems typology, the CHNS framework, and the broad ideas behind LCAs in measuring impacts across a system are tools that you can use to develop your ideas for the capstone project and other learning efforts beyond this course.

As you apply the CHNS framework and the LCA method, you'll be using a geoscience habit of mind introduced in module 1, that of systems thinking. Systems-oriented frameworks and methods are ways of interpreting and measuring complex systems in a way that incorporates the scale of an entire system as well as linkages among many interacting parts. As designers of this course, we believe that these frameworks and skills will be useful to you whether or not you go in some area of geosciences since systems thinking is a needed skill in today's complex world.

Goals and Learning Objectives

Goals and Learning Objectives

Goals

- Describe ways that food systems impact the earth system.

- Explain the characteristics and scale of the three major food systems coexisting in the world today and their overlap.

- Demonstrate the complexity and interconnectedness of food system types that connecting society to the environment in different ways within a globalized world.

- Construct an assessment that measures the impacts of food systems on the earth system and local environments.

Learning Objectives

After completing this module, students will be able to:

- Define food systems and name the component systems, the roles played by each, and the three dominant and overlapping types of food systems in the world today.

- Name different types of impacts of the food system on earth’s natural systems.

- Define the basic elements of a coupled human-natural system.

- Describe a life cycle assessment (LCA) and state what it is used for.

- Explain examples of food systems to illustrate and compare their combined social and environmental inputs and impacts.

- Apply the concept of natural human systems to food systems and distinguish different ways that food systems develop and change because of human and natural factors.

- Apply a coupled natural system framework to describe how human systems affect earth’s natural systems within food systems.

- Construct life-cycle assessments using data on food production activities that compare the impacts of different types of food systems on the earth systems.

- Synthesize outputs of LCAs you have constructed to compare impacts of different food production systems.

Assignments

Module 10 Roadmap

Detailed instructions for completing the Summative Assessment will be provided in each module.

| Action | Assignment | Location |

|---|---|---|

| To Read |

|

|

| To Do |

|

|

Questions?

If you prefer to use email:

If you have any questions, please send them through Canvas e-mail. We will check daily to respond. If your question is one that is relevant to the entire class, we may respond to the entire class rather than individually.

If you prefer to use the discussion forums:

If you have any questions, please post them to the discussion forum in Canvas. We will check that discussion forum daily to respond. While you are there, feel free to post your own responses if you, too, are able to help out a classmate.

Module 10.1: Food Systems

Module 10.1: Food Systems

What are food systems and what do they do?

This module builds on the introductory material in modules one and two defining food systems as coupled human-natural systems: human society interacting with the natural earth system. It marks the transition in the course to focusing on human food systems and land use and their impacts on the environment and earth systems.

Introductory Video on Food Systems

Introductory Video on Food Systems

In the introductory video below you will see a particular local example of a food system, presented by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. As you watch, look for examples of Human and Natural system components in a local food system particular to the Red River Delta in Vietnam, and the way that the food system has changed over time. Human and Natural system components were introduced in Module 1, and we have been referring to them regularly along the way in the course, as we have considered the natural system elements in agroecosystems and the way these are managed by humans. Now we will begin to take a larger, whole systems view of food systems.

Please watch the below video celebrating world food day 2013, which describes the Vietnamese “Garden, Pond, Livestock Plan” (V.A.C) food system.

Video: World Food Day 2013 [4] (6:52)

Food Systems: Environments, Production, Distribution, and Household Utilization of Food

Food Systems: Environments, Production, Distribution, and Household Utilization of Food

The introductory section below is adapted from "Chapter 3: The food system and household food security” at the document website of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization [5] (FAO).

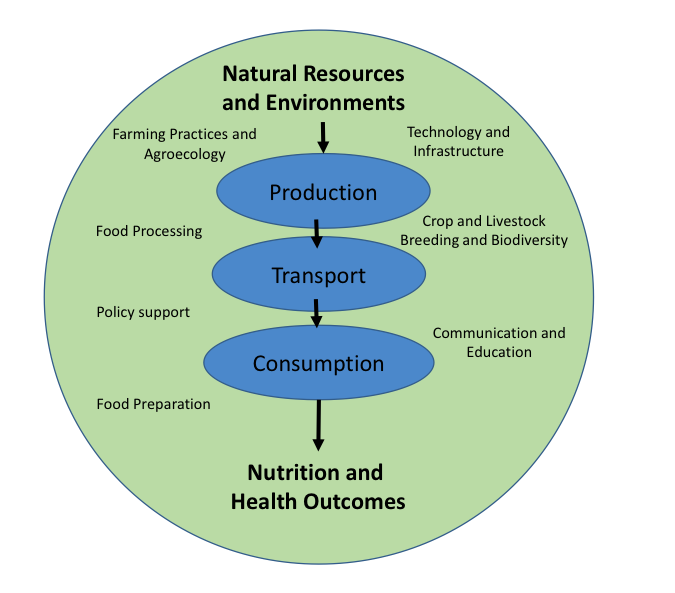

This section attempts to describe the parts of a food system in basic terms, starting from the standpoint of the systems approach. It begins, "the perception underlying the systems approach is that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Any situation is viewed in terms of relationships and integration. A food system may thus include all activities related to the production, distribution, and consumption of food that affect human nutrition and health (see Figure 10.1.1, which is reproduced from module 1).

Food production comprises such factors as the use of land for productive purposes (land use), the distribution of land ownership within communities and regions (land tenure), soil management, crop breeding and selection, crop management, livestock breeding and management and harvesting, which have been touched on in previous modules. Food distribution involves a series of post-harvest activities including the processing, transportation, storage, packaging, and marketing of food as well as activities related to household purchasing power, traditions of food use (including child feeding practices), food exchanges and gift-giving and public food distribution. Activities related to food utilization and consumption include those involved in the preparation, processing, and cooking of food at both the home and community levels, as well as household decision-making regarding food, household food distribution practices, cultural and individual food choices, and access to health care, sanitation, and knowledge.

Among the components of the food system, e.g. food processing, communication, and education, there is substantial overlap and interlinkage. For example, household decision-making behavior with regard to food is influenced by nutrition knowledge and by cultural practices with regard to food allocation within the household as well as by purchasing power and market prices."

Food systems are further embedded in environments and societies (thus, both natural and social/political contexts) which differ according to a variety of factors such as agroecology (the composition of the local agroecosystem, see previous modules), climate, social aspects, economics, health, and policy. The model presented in Figure 10.1.1 above is useful in conceptualizing the various activities that determine food security and nutritional well-being and the interactions within the food system."

Two important features that we want to emphasize in the passage above from the FAO are first, the fact that food systems involve processes at multiple scales (e.g. local agroecosystems, government policy at a national scale, international research and technology development), which eventually have many impacts at a household scale, either in the livelihoods of food producers (who gain income from the food system and also consume food); and also for consumers around the world. Second, criteria with which we should evaluate food systems are their ability to deliver nutrition and health outcomes (see e.g. module 3), and also the sustainability of natural resources and environments, which we will consider in module 10.2. We note that these criteria of environmental sustainability and health are at opposite ends of this "conveyer belt" model of food systems, where the food system "conveyer belt" can be said to deliver nutrition and health outcomes by transforming the inputs from natural resources and environments. These health and nutrition outcomes are associated with the concept of food security (sufficient access to appropriate and healthy food) which was introduced in module 3 and will be further explored in module 11. Human health and environmental sustainability correspond roughly to the positive objectives that we conceive of for the human system and natural systems, respectively: health and equitable nutrition (or food security) in the human system, and environmental sustainability of natural systems. A final observation from Fig. 10.1.1 is that food systems are ubiquitous and touch on all aspects of human societies. We are all participants in food systems, either as producers, consumers, in the distribution or in other myriad ways.

Activate Your Learning: Food's Journey in the Food System

Food systems comprise the interacting parts of human society and nature that deliver food to households and communities (see the previous page), and can be used to understand food in its relation to the earth system. To better understand food systems, in the exercise below you'll be asked to consider a familiar food of your choice, and the journey this food takes from where it is produced to the meals that we consume every day. Within the food supply chain for this food, you'll be asked to distinguish between social (human system) aspects and environmental (natural system) aspects of that product's food production and supply chain.

Activate Your Learning Activity:

In the blanks below, fill in the blanks regarding the supply chain for food products. You can also download the worksheet [7] for filling in offline, or as part of a classroom activity. As depicted in Fig. 10.1.3, you’ll need to give the origin, some intermediate destinations, and then the final consumption point for the food product. Then you should think of some social or human system dimensions of the production, supply chain, or consumption of this product, as well as some ecological or natural system dimensions and fill in the corresponding blanks. Do this first for a product familiar to you, whose supply chain you either know about or can research quickly (part 1). Then repeat the activity for a food product in the online introductory video from the first page of this module, about food systems in Vietnam (part 2). When you are done with each part you can click on the ‘answers’ link in the below each part, and see how your answers match up.

Fill in the blanks below. If you are doing this online, just note your answers on a piece of paper regarding the food product you have chosen, or download the worksheet [7]. When you are done you can click on the ‘answers’ link below to see some possible examples and see if your answers match up with these answers.

- Food product ______________________________

- Food supply Chain:

- Source: Where main raw material is produced, fished, hunted: ___________________________

- Intermediate destination 1: ___________________________ (e.g processing plant, washing, trucking, warehouse, etc.)

- Intermediate destination 2: ___________________________ (e.g processing plant, washing, trucking, warehouse, etc.)

- Intermediate destination 2: ___________________________ (if needed)

- Consumption point: ___________________________

- Up to three social or human system dimensions of this food chain (e.g. policy, economic, or cultural factors associated with the production and consumption of this food, recall the Human System factors in a Coupled Human Natural Framework, module 1.2)

- _______________

- _______________

- _______________

- Up to three ecological or natural system dimensions of this food chain: (ecological factors would include crop and animal species, agroecosystems, climate, water, and soil influences on food production):

- _______________

- _______________

- _______________

Example answers

(These may be a good deal more complete than your examples but give a sense of the range of possible answers)

Example Answer 1 - frozen, breaded fish filet from a local supermarket:

Click for the answer.

- Frozen, breaded fish filet (i.e., the fish part)

- Food supply chain:

- Fishing boat in Atlantic, Chinese, or Alaskan Fishery, e.g., including flash-freezing.

- Preparation facility in Canada or U.S.

- Cold chain shipping / Supermarket

- Kitchen oven and dining table for food preparation and consumption.

See some fascinating details about the production process, in How It's Made [8].

- Social dimensions:

- Financing, organization, and contracts for a fishing fleet and processing

- Government and fishing communities’ agreements on fisheries regulation to avoid overfishing.

- Supermarket companies

- Ecological dimensions:

- The wild fish species itself

- Food sources for the fish (algae, other fish)

- Changing ocean temperatures and conditions with climate change

Example Answer 2 - Bagel or bread from a local bake or coffee shop:

Click for the answer.

- Baked good (i.e., flour it is made from)

- Food supply chain:

- Farm in Midwest or Western U.S.

- Grain elevator purchasing and storing grain

- Flour production facility

- Café or restaurant kitchen (may be a large centralized kitchen for a chain restaurant) and coffee shop table for consumption.

- Social dimensions: (could include any of these)

- Farm enterprise belonging to a farm family or company – organization of production labor and agroecosystem management.

- Supply chains and companies for fertilizers, seed, and other agricultural inputs

- Government policies regulating subsidies to farmers, tax on diesel fuel, pollution regulations etc.

- Grain commodity markets and corporations

- Ecological dimensions:

- Domesticated wheat species (Triticum aestivum)

- Prairie soils (Mollisols) with inherent good qualities and climate for wheat growing

- Soil bacteria breaking down organic matter, releasing nutrients, accessing fertilizer N and releasing nitrous oxide.

- Bread yeast and/or sourdough bacteria used in bread making.

Exercise 2:

Recall the video celebrating world food day 2013, World Food Day 2013 Video: the Vietnamese “Garden, Pond, Livestock Plan” (V.A.C) food system" [4]. You may want to quickly skim the video again and note the food pathways that foods are following in these systems. Then choose either a product that is consumed within the household that appears in the video or one that is sold outside the household (some products fit into both categories). Fill in the same set of production and transport steps for this product as you did in part 1, as well as some social and ecological aspects. You can use a piece of scrap paper or the downloaded worksheet. Note that a product consumed in this farming household may have a very short food supply chain!

Look at the following worksheet and fill in the blanks corresponding to the blanks below. When you are done you can click on the ‘answers’ link to see some possible examples and see if your answers match up with these answers.

- Food product ______________________________

- Food supply Chain:

- Source: Where main raw material is produced, fished, hunted: ___________________________

- Intermediate destination 1: ___________________________ (e.g processing plant, washing, trucking, warehouse, etc.)

- Intermediate destination 2: ___________________________ (e.g processing plant, washing, trucking, warehouse, etc.)

- Intermediate destination 2: ___________________________ (if needed)

- Consumption point: ___________________________

- Up to three social or human system dimensions of this food chain (e.g. policy, economic, or cultural factors associated with the production and consumption of this food, recall the Human System factors in a Coupled Human Natural Framework, module 1.2)

- _______________

- _______________

- _______________

- Up to three ecological or natural system dimensions of this food chain: (ecological factors would include crop and animal species, agroecosystems, climate, water, and soil influences on food production):

- _______________

- _______________

- _______________

Example Answers

Example for the Vietnam VAC food system example:

Click for the answer.

- Food Product: Fish from the fish pond in the video

- Food supply chain (if sold):

- Brought from pond

- Transported by cart or truck to city

- Sold in market

- Prepared at home

- Brought from pond

- Prepared and eaten.

- Social dimensions: (could include any of these)

- Farm enterprise belonging to a farm family – production roles of family members

- Government policies promoting choice by farmers of what to grow and the ability to market it (note as a communist government there was a time when this was not allowed)

- Government and community efforts to promote and adapt the V.A.C. food production methods.

- The organization of local markets and food sellers that allows farmers to sell products.

- Ecological dimensions:

- Fish species e.g. carp

- Pond / Garden agroecosystem

- Recycling of organic wastes from fish production into soils

- Rainy climate/river delta geography and abundant water for fish and crop production.

Spatial Scale and Typologies of Food Systems

Spatial Scale and Typologies of Food Systems

A good way to understand the complexity of different types of food systems is to look for organizing principles to classify them. In the introductory food supply chain exercise at the beginning of this module, if you chose a product that was produced a long distance from where you consumed it, you are aware that the global food system today handles food at an enormous spatial scale. This example leads to one way to organize our understanding of food systems, which is the hierarchy global, regional, and local scales of food systems (Fig. 10.1.4).

| Scale | Examples |

|---|---|

| Global | Global grain and meat production (commodities), Global fisheries |

| Regional | Most supermarket and restaurant foods |

| Local | Farmer's market, local hunting and fishing |

| Household | Home gardens and subsistence agriculture |

Another helpful way to classify food systems is to look for typologies of food systems. Building typologies is a somewhat subjective but often helpful process where we look for groups of systems or components that hang together in order to better understand their function, importance, or other attributes. For the typology of food systems we present here, we are thinking about classifying food systems based on how production occurs and at what scale, which portions of society are involved in production and distribution, and the rationale underlying production, distribution, and consumption. In this course, we use the scheme of three overlapping food systems that exist at global, regional, and local scales shown below in Fig. 10.1.5.

Global Corporate Food System

- High volume, minimized production costs

- Simplified farms that specialize in particular crops

- Global and regional shipping

- Unprocessed and processed foods

- Coordinated through major agribusinesses and food companies

- Goals: markets and return on investment

- Local producers participate via commodity production

Smallholder Food Systems

- Smaller-volume production on many more farms

- Complex, diverse farming systems with e.g. livestock and many crops

- Local/regional shipping and marketing

- Unprocessed foods

- Goals: generating farmer livelihoods and food for direct consumption and local markets

- Mixed production and consumption roles

- Produces a large proportion of food in developing countries

Alternative Food Systems: Globalized and Community-based

- Globalized

- "Ecological modernization" of globalized food system

- Global/national trade networks

- Goals: reform of industrialized farming practices

- Certification schemes: fair-trade, sustainable forestry, etc

- Unprocessed and processed foods

- Mainstreaming of organic products in national/global distribution

- Community-based

- Emphasis on reintegration of local rural-urban economies

- Goals: reform of industrialized farming, local economies

- Local/regional shipping and farmers' markets

- Mainly unprocessed foods

- Organic and local criteria/certification

The Globalized Corporate Food System

The Globalized Corporate Food System

Consumers worldwide who enter a supermarket are largely interacting with this type of food system. Some local and regional products are provided, but food is largely sourced from major national and global production regions and can be transported long distances (100 to thousands of miles or km) with enormous quantities of food moving through the system as a whole. There is an emphasis on modern production and processing techniques, efficiency, and lowering the immediate costs of production. Also, many of the products moving through this system are thought of as commodities: products that are generic and replaceable regardless of their origin and that carry standard global and national pricing frameworks. Examples would be corn grain for food, different grades of rice, soy and corn oils, supermarket potatoes and tomatoes, and cuts of pork for supermarket consumption.

Globalized Corporate Food System

- High volume, minimized production costs

- simplified farms that specialize in particular crops

- global and regional shipping

- unprocessed and processed foods

- coordinated through major agribusiness and food companies

- goals: markets and return on investment

- local producers participate via commodity production

Calling this a ‘corporate’ system may obscure the fact that production for this national/global scale system occurs most commonly not on corporate property or company farms, but in family farm enterprises like the thousands of dairy and grain farms that populate many regions of the United States. For example, family farms still constitute about 97% of farms in the United States by number, although the acreage in company-owned farms and the value earned by these company-owned farms is larger than this numerical count suggests (top pie-charts within Figure 10.1.8a below). Also, in some areas of the country, ‘large’ and ‘very large’ family farms have mean farm sizes of many thousands of acres, which contradicts the traditional image of a small family enterprise, and illustrating the pressures for farms to become large in modern industrialized food systems, in order to take advantage of economies of scale in farming (economies of scale refers to the idea that as the size of an enterprise goes up, the efficiency of producing a given item goes up and the cost per item goes down, e.g. baking one tray of muffins every Saturday versus opening a muffin shop making hundreds of muffins every day).

Nevertheless, this portion of the food system is called both ‘global’ and ‘corporate’ because most organizations that coordinate demand and organize processing and distribution of foodstuffs in this layer of the global food system are corporations seeking benefit for their shareholders. In module 3 on nutrition we discussed the way that food has become fiscalized, i.e. it is not only a product working its way through a marketplace to consumers but an active object of investment in the future growth potential of the business of food. These investments are managed through large-scale exchanges like the stock exchange here in the United States. These exchanges allow large swaths of relatively wealthy world citizens (including many in the middle class) to invest in the large-scale production of food and reductions in prices, but can create sustainability issues within the food system because the return on investment rather than food security or environmental sustainability becomes the predominant objective of investors and corporations. Nevertheless, not just corporate entities but also government and civil society (e.g. farmer and community organizations, universities) are also heavily involved in these global systems and can act to reform problems or regulate damaging or unjust practices. They act by way of advocacy and regulation, national/international food policies and support structures such as research on food production and food processing methods.

Within this global system, then, local farmers and fishing communities often act as producers selling into commodity markets, alongside industry-owned farms, feedlots, and other production facilities. In addition to unprocessed food ingredients, the globalized corporate food system has also been largely responsible for the expansion in processed and prepared foods, that seeks to provide convenience for consumers as well as capture the added market value of more prepared foods. Processed foods have been criticized, especially by those advocating community food systems (see description further on), because they displace fresh and whole food components of diets that are important to good nutrition outcomes (see module 3). Processed foods often contain processed industrial ingredients such as corn syrup and processed, low-quality fats along with a lower fiber and vitamin content, which is usually not true of whole unprocessed foods.

Farms and acreage of different crops in United States agriculture:

The pie charts below demonstrate aspects of the description of the globalized food system above. For example, at least in terms of numbers, smaller, family-owned farms with an average size of approximately 240 acres (around 100 hectares with one hectare = 100 x 100 m) dominate the numbers of farms in the United States (Fig. 10.1.8a). Nevertheless, large farms dominate to a greater extent than these smaller farms when considering the total area taken up by farms of different sizes, and a large proportion of income is going to larger operations in a number of classes of farm products (Fig. 10.1.8b). These patterns vary somewhat by what sector of the farming economy is being described, and we include some separate graphs for maize, vegetables, and dairy farms. You will use these graphs in the knowledge check activity below.

Knowledge Check: Food products and farm sizes in U.S. agriculture

Choose the correct answers based on the graphs in Figure 10.1.8 above and then click on the space for the correct answers.

Question 1 - Short Answer

Which food product type (maize, vegetables, dairy) above had the largest participation of non-family owned farms, in terms of revenue from sales of that food product type?

Click for the answer.

Vegetables. This means that in Maize and Dairy production, family-owned farms are more important in terms of total earnings.

Question 2 - Short Answer

Which crop type above has the largest participation of family-owned farms in the SMALL category, in terms of value sold?

Click for the answer.

Maize

Question 3 - Short Answer

These charts don’t show the large variation that exists in the distribution of farm sizes around the country, which you will want to incorporate into your capstone project for your capstone region. If you have looked up this information for your capstone, does your capstone region have a smaller or larger average (or median) farm size?

Click for the answer.

Here are some answers for different regions of the country that should help you to estimate how farm size varies: California – in line or larger than these figures; Colorado: in line with these figures on farm size; Pennsylvania: smaller. In particular, the Pennsylvania dairy sector is much less dominated by very large and corporate farm holdings. This is information you will be able to find in the USDA Census county-level reports, which give a breakdown on farmland areas for each county in the United States.

Question 4 - Short Answer

How do you think the “small” category of U.S. farms in land area (236 acres or just under 100 hectares) compares to the average landholdings of the “small” category for countries like Peru, Kenya, or India where smallholders (farmers on relatively small land areas) are a large part of the population?

Click for the answer.

The median small farm size of smallholder farmers in these countries is much smaller, often 10 acres (3-4 hectares) or less, which is less than a tenth of the "small" family farm in the united states.

Smallholder Farmer Food Systems

Smallholder Farmer Food Systems

Approximately 500 million smallholder farms with areas less than 2 hectares (5 acres) support the nutrition and livelihood of approximately two billion people in smallholder farms globally (IFAD, 2013). As such smallholders form an important sector of the global food system, producing up to 80% of local and regional food supplies in Sub-Saharan Africa, South/Southeast Asia, and China. You saw an example of a smallholder system in the summative assessment for module 1. Livelihood strategies of households in this system attempt to overcome risk and guarantee subsistence as well as cash income. For this reason, these "semi-subsistence" farming systems are often complex, for example integrating agriculture, livestock, and agroforestry food production with off-farm livelihood activities that overlap with consumption from the globalized food system (previous page). Most food is consumed either on the farm where it is produced or locally and regionally, with transport and distribution handled by relatively short-distance networks.

Alternative Food Systems: Global and Local Variants

Alternative Food Systems: Global and Local Variants

"Quasi-Parallel" Alternatives to Modern Food Systems

You may recall that the concluding section of module 2 on the history of crop domestication and food systems we presented the recent development of alternatives to the modern globalized food system as "quasi-parallel" new movements as well as food production and distribution strategies intended to address sustainability issues. We use the word "quasi-parallel" because the global and local variants of these responses focus on different strategies and scales within the food system, and target different outcomes, even though both consider themselves to be responding to the sustainability challenges in the modern food system, sometimes using similar practices at the farm scale for managing crops and soils. Also, we acknowledge at the outset that dividing these strictly into two variants may not cover every case. The intention is to give you a sense of the range of alternatives being proposed so that you can potentially look for these types of alternative food systems in your capstone regions and integrate them into proposed sustainability strategies for the future of food in these regions. Also, it is likely that both variants will have advantages and disadvantages that are pointed out and debated by proponents and critics. From this debate we can see that sustainability is a contested concept, depending on the assumptions, goals, and arguments used by different advocates: it does not have a single definition to different camps in the debate over sustainability.

Globalized Alternatives: "Ecological Modernization" as a Reformation of Globalized Food Systems

Globalized variants of alternative food systems seek to correct issues of sustainability from within the framework of global food production and food trade networks. This has been called a case of "ecological modernization" because it seeks to reform certain aspects of globalized corporate food systems (previous pages) such as environmental impact and labor standards, while not altering the main features of the modern global system, for example, large scale of production, long-distance distribution, and leveraging the economic power of global investment to expand production and increase efficiency. Advocates of this approach promote strategies such as the "triple bottom line" for companies, which refers to positive environmental and social benefits from company activities being measures of company success in addition to economic profitability (thus a triple measure mirroring the "three-legged stool" of sustainability, see Module 1 and following pages in this module). Advocates also generally point to the fact that given the globalized corporate food system embodies by far the largest impact on levels of social equality and natural systems currently, reforming its activities and standards for performance is a way to have a tremendous impact on global sustainability. Detractors of "ecological modernization", including advocates of community-based food systems below, complain that these reform efforts leave in place unsustainable features of the system, such as large-scale production that is corrosive to local communities, or marginalization of smallholder farmers within markets or in land distribution in some cases (see the "agriculture of the middle" critique and the concept of a poverty trap in the following pages).

Notwithstanding this debate, it is useful to note some main features and trends in this globalized approach. Like the community-based variant, the globalized variant has prescriptive goals for the food system in response to sustainability problems of the modern food system. It supports substitution of more sustainable methods of food production, such as integrated pest management, organic methods, reduced tillage, and protection of watersheds from pollution with improved farming techniques, some of which have been seen in previous modules. Certification schemes are promoted that hold producers and distribution networks to a higher standard, such as organic certification (which generally must conform to standards in the country where the food product is sold). As another example, fair trade certification seeks to improve the price paid to local producers in source regions, who have generally received very low prices for their products, and thus shares the approach of strengthening local economies with the community-based approaches below, even if it uses global trading networks.

Alternative Food Systems: globalized and community-based

- Globalized

- "ecological modernization" of the globalized food system

- global/national trade networks

- goals: reform of industrialized farming practices, capturing market niches

- certification schemes: fair-trade, sustainable forestry, etc.

- unprocessed and processed foods

- mainstreaming of organic products in national/global distribution

- Community-based

- emphasis on reintegration of local rural-urban economies

- goals: reform of industrialized farming, local market reintegration, market niches, local/regional shipping and farmers' markets

- mainly unprocessed foods

- organic and local criteria/certification

Community-based Alternatives

Like the globalized variant, community-based alternative food systems define prescriptive goals but oppose many elements of the globalized corporate food system. The community food system primer (Wilkins and Eames-Sheavly 2010, see link below if further interested) states that "a community food system is a food system in which food production, processing, distribution, and consumption are integrated to enhance the environmental, economic, social and nutritional health of a particular place". Three examples of these prescriptive goals within common components of community food systems are:

- Organic agriculture as a way to reduce contamination of food with pesticides and improve the ecosystem health of farms

- Farmers markets and community-supported agriculture schemes that allow consumers to more directly support the activities of farmers

- An emphasis on supporting the activities of small and medium producers and resisting pressures for production and distribution enterprises to grow larger and larger

Many other examples of community food systems can be found, which also include efforts to link smallholder farmers and their food production systems (see previous page) as producers for burgeoning urban markets in developing countries, thus substituting some of the supply from the globalized corporate food system beyond the food products that are already supplied by smallholders to cities in these countries. The overall volume of food handled by these community-based food systems is generally much smaller than the globalized or smallholder types of food systems. Nevertheless, advocates point out that the potential market of urban consumers in relatively close proximity to small-scale producers around the world is potentially enormous. In fact, channels of alternative food production and distribution (e.g. organic agriculture) are among the fastest growing sectors in volume and economic value on a percentage basis, year after year [USDA-Economic Research Service [9]].

Additional Reading:

- A Primer on Community Food Systems [10]: Read the Introduction, Community Food Systems, and Goals of Community Food Systems.

Knowledge Check: Food System Typologies

For each of the following concepts, give which of the three types of food systems it pertains to (global corporate, smallholder, local/alternative).

- Shareholders invest in food companies

- Fairtrade organizations link smallholders in Kenya to consumers in the U.K.

- A dairy farmer sells small lots of milk using weekly deliveries to a mid-size city in New Hampshire.

- Most supermarket items

- Very important in densely populated rural areas of the developing world e.g. Ethiopia, Peru.

- Buying butternut squash at the local farmers market.

- Large wheat fields near Ciudad Obregón, Mexico for export to processors in Mexico, United States, and Colombia.

Scoring your answers to the knowledge check:

Click for the answer.

- global corporate

- global alternative

- local community-based, alternative

- global corporate

- smallholder

- alternative community based

- global corporate

Challenges to Producers: Sustainability and "Poverty Traps"

Challenges to Producers: Sustainability and "Poverty Traps"

- Environment

- reduce pollution and waste

- use renewable energy

- conservation

- restoration

- Community (and social sustainability)

- good working conditions

- health care

- education

- community and culture

- Economy

- employment

- profitable enterprises

- infrastructure

- fair trade

- security

Challenges to Food Producers: The issue of scale and the “three-legged stool” of sustainability

The previous page on different variants of alternative food systems stressed different ways of analyzing and critiquing the modern global food system based on issues of sustainability. In your capstone projects, you are asked to propose ideas for sustainable food systems in your capstone regions. Therefore, in this page, we repeat from module one the concept of sustainability as a "three-legged stool" combining aspects of environmental, social, and economic sustainability (Fig. 10.1.15, also seen in module 1). We may be most used to thinking about Environmental Sustainability, for example in the need to conserve energy or recycle food containers to reduce pollution and energy generation by fossil fuels, as well as avoiding litter and saving on landfill space. As we presented in module 1, however, sustainability also contains economic or financial aspects devoted to employment, livelihood, and profitability, as well as the concept of social sustainability that embodies goals of social equity and more harmonious societies. Therefore, we are also interested in the nodes of food production such as farms because of the challenges to the economic sustainability of farm (and fishery) enterprises. It is important to think about economic sustainability because of the economic risks that food producers are exposed to. Economic risk is inherent in producing for local, regional and global food systems because producers may not be producing high-value products and must absorb environmental risk, for example from droughts, floods, or pests (see the previous modules, and module 11, next, regarding adaptive capacity). In a drought year, for example, selling vastly reduced yields of soybean or maize crops usually mean an economic loss for a farm because the price of these crops is not very high on the global or local market.

In addition, social sustainability concerns regarding food production are an important part of debates about modern society: for example, smallholder farmers, and laborers on larger farms and within fisheries in the United States and globally, are some of the most economically and politically marginalized populations in the world. Many researchers and advocates point out that food systems cannot be truly sustainable until they embody a more just distribution of resources and power. In this short section, we want to highlight two important concepts that link to these ideas of social sustainability and justice: first, the idea of “poverty traps” within smallholder farming around the world (see Carter and Barrett 2006, reference below), and on the next the threat posed to so-called “agriculture of the middle” in industrialized countries where pressures on producers lead either to a small-scale, niche markets orientation (e.g.. farmers markets) or an inexorable growth toward larger and larger farms that capture economies of scale in agriculture. By introducing these concepts now, you should see both how they fit into the analysis of vulnerability and resilience in the next module. You may be able to incorporate these challenges and potential solutions into your capstone region scenarios.

What is a poverty trap in smallholder agricultural systems?

As you’ve seen in the “pond-garden-livestock” (VAC) system of Vietnam in the video at the beginning of this module, agriculture practiced in smallholder food systems on small plots of land (less than 10 acres or 4 hectares, say) around the world is a hugely important and often quite sustainable enterprise. Smallholder agriculture can embody some of the most efficient use of resources in use today, whether these are traditional methods, well-adapted domesticated plants, new innovations taken up by smallholder families, or labor that is efficiently allocated by a family that is in constant contact with their enterprise and ecosystem. However, a concern about the most impoverished smallholders is that they can fall into what is called a poverty trap, where smallholders produce food from a degraded resource base, either because they have degraded it or because they have been forced to the margins of local society, and many times, both. The diversity of diets can also suffer when the least expensive food sources are local cereal and starch crops or calories coming from the globalized food system. The combination of poverty and degradation of soils and other resources does not permit these farmers sufficient income or well-being to invest in and therefore improve their soils or other aspects of local agroecosystems, and so it is likely that they, and their farm ecosystems, will remain in a low level of productivity and earnings. This is therefore called a poverty trap, and it essentially combines a lack of economic, social, and environmental sustainability for these smallholder households. It has also been linked to the concept of a downward spiral of poverty and soil degradation (Fig. 10.1.16).

An example of this poverty trap "downward spiral" is furnished by the dust bowl of the 1930s in the United States, in the case of many families who farmed small plots of land during the depression. The combination of overexploited soils from decades of agricultural expansion after the U.S. civil war, a depressed economy contributing to overall hardship, and a multi-year drought led to a downward spiral in which many poor farmers were finally forced to leave their land and migrate to other areas of the country seeking employment and public assistance. In module 11, we'll examine further how combined human and natural system factors (like poverty and drought, for example) interact to create vulnerability for parts of human society, and ways that human systems have adapted to surviving such shocks and perturbations as drought. We'll include an example of a native American population that was relatively successful in weathering the Dust Bowl and was not subjected to this sort of poverty trap or downward spiral. Also, in the years after the dust bowl, the Soil Conservation Service of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) was highly active in helping farmers to transition to practices that helped to avoid soil erosion and aid in regeneration of degraded soils (see the additional reading resources below for this history of the Soil Conservation Service).

In current-day contexts where poverty traps represent a risk or chronic problem for small producers, then, both government agencies and development organizations focus on reducing barriers to practicing more sustainable agriculture. Development organizations include those called non-governmental organizations or NGOs, nonprofits, international aid organizations, as well as organizations founded by and managed by farmers themselves. For example, see the blog article below in "additional reading", regarding efforts to promote agroforestry in Haiti, where poverty and land degradation have long been intertwined. These organizations try to reduce barriers to investment in sustainable food production through the promotion of simple, low-cost strategies to conserve soils and raise crop diversity and productivity (see the previous modules for examples) that are within financial reach of smallholder producers. These technology options are optimally combined with credit and direct aid that helps farmers to overcome the resource barriers for investing in the protection of the natural systems that sustain their production. This sort of knowledge and technology, and the ability of farmers to invest in the productivity of their soils are an example of adaptive capacity, a concept that will a major topic of module 11. In addition, government, NGOs, and farmer organizations may also engage in political advocacy that seeks a more just distribution of land, credit, or access to markets that can help producers to avoid or move out of poverty traps.

Additional Reading:

- Carter, Michael R., and Christopher B. Barrett. "The economics of poverty traps and persistent poverty: An asset-based approach." The Journal of Development Studies 42.2 (2006): 178-199.

- Jacquet, Bruno: blog article, Agroforestry & Sustainable Land Management in Haiti [11], documenting efforts to promote agroforestry in Haiti with smallholder farmers.

- Natural Resource Conservation Service (USDA): web page giving a brief history of the dust bowl and the soil conservation service, which became the Natural Resource Conservation Service [12].

Challenges to Producers: Sustainability and "Agriculture of the Middle" in Globalized Food Systems

Challenges to Producers: Sustainability and "Agriculture of the Middle" in Globalized Food Systems

One of the characteristics of a globalized food system is that a smaller proportion of the population is needed to produce the large amounts of food for the global system. As a result, many analysts have noted shrinkage of the rural population in the rural United States over the last 100 years. Similar out-migrations from rural areas to cities have happened in Europe. Among other factors, this process has been hastened by the use of mechanization for agriculture (tractors, combine harvesters, mechanized crop processing, and transportation; we analyze the environmental impact of this in module 10.2). Mechanization and other factors mean that the cost of producing a bushel of corn, for example, and moving it into the global food system is cheaper when the scale of the farm and transportation infrastructure is larger. This phenomenon is referred to as economies of scale (recall also the example of dramatically scaled-up beef production in Greely, Colorado featured in the video of Module 1.2.) Farm producers in the United States and other industrialized economies thus often face pressures to grow their operations larger so that they can become more profitable, accentuated by competition against larger producers with lower prices, sometimes in other countries with lower labor prices.

These twin trends towards “get big or get out” and “get small for local markets” have left out a huge sector of farms that are mid-sized and that still generate a substantial amount of farm income in the U.S. economy and utilizing the lion’s share of cultivated soils (see figure 10.1.8 with pie-charts of earnings distributions different size farms in the United States). The analysis regarding this “Agriculture of the Middle” (Kirschenmann 2012) points out the threat posed to millions of farming households, most of whom produce for national and global commodity markets (e.g. soybeans, dairy). This analysis also points out that this sector of farms is vital as productive rural citizens that drive social organization, effective policy-making, and community values in most regions of the country. These mid-size farms are often leaders in the adoption of sustainable practices – especially when they are financially successful, illustrating potential linkages between financial and ecological sustainability. In any case, small and medium-sized farms have always played an important role in the maintenance of a rural landscape that most governments and citizens see as valuable. Agricultural landscapes and enterprises often contribute to the tourism value of a particular region, for example, the Pennsylvania Dutch region or wider presence of dairy farms in diverse, forested landscapes of Pennsylvania, or wine-producing regions of California and New York State.

The role of “Agriculture of the Middle” in sustaining rural life according to this analysis is worth protecting, and advocates of this analysis and action to support mid-size farm enterprises point out a few advantages these farms have in interacting with regional farm systems. When effective linkages can be built to regional markets, these farms usually combine production at a medium to large scale (compared to small diversified farms supplying farmers’ markets, say) with a flexible outlook that can allow them to change products and markets quickly, and best adopt sustainable production methods in a way that is visible to consumers and local communities (Kirschenmann 2012). As in the case of poverty traps for small farms discussed above, organizations that promote agriculture of the middle seek to clear barriers to these mid-sized producers. Note also that these “mid-sized” producers are enormous compared to farms in smallholder contexts throughout the developing world, though they are community members in an equivalent way to the role of smallholders in a rural third-world context). Mid-size producers and the food distribution organization that work with them may seek to promote “values-based food supply chains” where not just the commodity value of a food product is taken into account but also the value of a farm that demonstrates environmental sustainability and positive participation in rural communities. For example, many agricultural states now have state-level marketing efforts that promote state and regional agriculture, and these programs increasingly integrate ideas that help to promote mid-sized producers. Farmers, distribution network companies, and food markets have also banded together in different configurations to form networks that seek to support not only food availability for consumers but environmental, social, and economic sustainability along the entire food chain. Some examples of these are the Organic Valley dairy cooperative which now operates across the entire United States, the Red Tomato regional fruit and vegetable marketing effort in New England, U.S.A. (see Fig. 10.1.17 and 10.1.18), or the Country Natural Beef producers in the Northwest United States.

More Information on Values-Based Food Supply Chains

You can view a PowerPoint slide set introducing nine case studies on values-based food supply chains like the ones described above: Agriculture of the Middle [13], a research and education effort of the University of Wisconsin.

Integration into the Capstone Project

As you consider the food system of your capstone region, you may want to incorporate references to efforts that support either smallholder farmers in avoiding poverty traps or encourage continued participation of “Agriculture of the Middle” in the regional food system. The formative assessment for this module asks you to address whether you think there are concerns about poverty traps or agriculture of the middle in your capstone region. As you develop your capstone project final scenarios for sustainability, you may want to search on the internet for resources on regional food chains and food systems, as well as local farmers' markets and other initiatives, within your region of interest.

Food Systems as Coupled Natural-Human Systems

Food Systems as Coupled Natural-Human Systems

As you saw in the introductory video about a food system in Vietnam, food systems incorporate both natural and human components. In fact, because of the ubiquitous need for food, food systems are among the most important ways that human societies interact with the physical and biological elements and processes on earth's surface. Land used in some way for food production already occupies over two-thirds of the ice-free land surface (Ellis, 2011 or similar on anthromes) and the trend is for this proportion as well as for the intensity (roughly, the production from each unit of land area) to increase. Human fisheries and other forms of food production from oceans (for example, kelp farming) are also tending to exploit wider and wider areas. In addition, as seen in the multiple types of food systems presented above in section II of this unit, the interactions of human societies with earth's ecosystems in food production is not governed by a single human process but depends greatly on human priorities, land management and food production knowledge, rationales and prescriptive goals for food systems, and government policies that regulate and reward food system outcomes. Understanding these societal factors is key to improving the sustainability of food systems in their impact on the earth's ecosystems.

To understand the interaction of human societies with the earth's surface, a common and productive framework is that of coupled natural-human systems [Liu et al., 2007]. These start from a relatively simple diagram (Fig. 8.9), in which a generic human system (e.g. a community within a human society) interacts with a generic natural system (e.g. a farming-dominated landscape within a production region). The framework also recognizes that natural and human systems have many internal interactions and processes such as biogeochemical nutrient cycling (e.g. the nitrogen cycle, see unit N.N in this course) or the policies, corporate actors, and markets determining food supply chains (a human factor).

Generic Natural-Human system that can be applied to the food system in its interactions with earth system processes

Arrows labeled human to natural coupling and natural to human coupling form a circle between human system and natural system. Those are defined as follows:

Human system: human system internal interactions

Human to natural coupling: Human system impacts and reorganizes natural system

Natural System: natural system internal interactions

Natural to human coupling: Natural system a)presents food production conditions to the Human System b) responds to human management and other drivers in ways that affect the human system (feedbacks)

So, for example, in the video that you watched on the food system from the Red River delta in Vietnam, the river delta is the initial, broad natural system context that presents opportunities for farming, livestock production, and aquaculture to farming households and national/local government policies. Human farming/aquaculture knowledge and practices, markets and government policies are part of a human system that impacts and reorganizes the natural system over time into its current state. Over time the natural system internal interactions and processes may also change, for example, increases or decreases in soil fertility, crop pests, or animal diseases. Because of the evolution over time of the system, it is useful to reorganize the coupled natural-human system as evolving over time (Fig. 8.10).

Divergence and Transition of Food Systems: Human-Natural Interactions

Divergence and Transition of Food Systems: Human-Natural Interactions

Overlap and Transition in Food Systems

As a final observation about ourselves as consumers within different food system types, it is important to stress that most consumers and households participate in multiple types of food systems at once. For example, someone in a modern society might consume a breakfast energy bar with globally sourced processed ingredients, along with a fair-trade certified cup of coffee and regionally sourced milk, on the way to picking up sweet corn at a direct-marketing farm stand of a local farmer. In addition, and of special importance for thinking about sustainable scenarios for your capstone project, it is important to find explanations of how transitions occur in food systems from one type of predominant system, to the inclusion of alternatives, or in some cases a wholesale change from one food system type another.

Human-Natural Interactions as Drivers of Food System Variation and Transitions

Recall that in Module two we presented the broad strokes of the history of food systems, from prehistoric times to the modern-day, including the globalized and local-regional variants of alternative food systems that were featured on the previous page of this module. In module two, we presented the idea of drivers and feedbacks that have caused large changes in the environment-food relations over human history (for example, from hunting and gathering to agriculture). In this final page of module 10.1 we want to develop concepts that constitute Coupled Human-Natural Systems explanations or "ways of seeing" that can help to understand two different processes:

- The way that two different and parallel food systems can exist in the same place, based on divergence from a common origin

- The transition from one food system type to another, considering the three major types of food systems and the different variants of alternative food systems.

Both of these ways of seeing may be useful in understanding proposals for sustainable food systems, as well as the issues of resilience and vulnerability of food systems presented in the next module.

Regarding process (1) above, The fact that food systems develop over time due to the interactions of human and natural systems means that different food systems can develop in the same natural system environment. For example, the same environment or natural system can support either a smallholder type of food system (small plots, less mechanization, local consumption) or a global corporate food system (larger land sizes, more mechanization and industrially-produced soil inputs, global distribution and consumption). It can also support a mosaic of the two types. This overlay of two types is in fact fairly common: for example, smallholder agriculture on smaller plots for mixed home and regional consumption coexists in Central America with the export agriculture of major food commodities such as bananas or vegetables, and often involves marginalization of smallholders to smaller landholdings in less productive and more difficult to manage soils. This mosaic of food system types is also increasingly true in Southeast Asia as globalized agriculture for cassava and maize production for export to China as well as domestic consumption coexists with more traditional smallholder agriculture as portrayed in the Vietnamese "VAC" system in the introductory video for this module. Figure 10.1.19 shows how two parallel food systems can develop in the same environment according to the Coupled Human-Natural System diagram we have seen at other points in the course. Starting at "time 0" in the middle we can see how an initial food system type might develop via human system management (e.g., the smallholder system in the Central American or Southeast Asian case). At "time 1", meanwhile, differences in the human system (say marginalization of smallholders to certain environments, investment in industrial farming in other environments) have created two divergent food system types. These divergent types then develop on their own through times two and three, and into the future, incorporating interactions between human and natural systems that embody the issues of social, financial, and environmental sustainability. As we can see by the Central American and Southeast Asian examples, this parallel trajectory of two different food system types is highly relevant, since it represents exactly what has happened in developing countries that seek to industrialize their agricultural sectors but retain a large rural population practicing smallholder agriculture, often in more marginal regions with greater heterogeneity of environments (e.g. mountainous areas of Central and South America, mosaics of large export-oriented farms alongside smallholder agriculture in South and Southeast Asia as well as Eastern and Southern Africa)

Regarding the transition from one food system type to another (process 2 as listed above), the CNHS diagram (figure 10.1.20 below) can help to understand these transitions. As an example, we'll use the transition to alternative food systems from the globalized industrial food system we described in module two and again in this module. In figure 10.1.19, between the "initial coupling" point at center and "Time 1", expansion of a dominant food system begins to create strains on both the natural and the human components of the system. In the case of the globalized industrial food system that emerged in developed countries (sometimes called the global north) after World War II, this system eventually created strains in the natural and human systems and a critique responding to the unintended consequences of the expansion of this industrial and globalized model. You'll recognize these strains and critique as the same issues of sustainability discussed in the previous modules:, "diseases of affluence" from poor nutrition, food insecurity, concerns about water use and the water footprint of food, soil degradation, pest and weed resistance to pesticide and herbicide management, and others. Between Time 1 and Time 2, the human society thus receives signals from the interactions and drivers within the coupled system, and then responds, in the form of a wide range of new policies and "models" of the new system that emerge during Time 3. In some cases, these responses are modest, for example, a new regulation on fertilizer or pesticide application to moderate the unintended negative consequences. In other cases, the responses are more dramatic and become the alternative food system types described in this module, both global and community-based. These different variants of the transition may increasingly create aspects of a "complete" food system, e.g. production, distribution, and consumption pathways in an integrated whole, as compared to their initial state as outliers, regulations, or policy proposals. Through different drivers and feedbacks from the natural and human sub-systems, a transition to new food system types occurs. These new types often coexist with a more dominant food system, which is certainly the case with the coexistence of alternative food systems in the present day with the still-dominant global corporate food system.

Module 10.2: Assessing Food System Impacts on Natural Systems and Sustainability

Module 10.2: Assessing Food System Impacts on Natural Systems and Sustainability

Introduction

What are the impacts of Food Systems on the Natural Systems that support our food production? You will learn about system-level impacts and impact assessment in module 10.2. You have already considered many of these impacts on the environment in earlier modules, for example, plant domestication, nutrient cycling, water use, and water pollution. You will learn about assessing impacts that emerge from the behavior of a whole food system, and practice life cycle assessment (LCA), one method used for assessing whole-system impacts.

Earth System Impacts and Energy Use by the Food System

Earth System Impacts and Energy Use by the Food System

Human System Impacts on the Environment Within Food Systems

In modules one and two of this course, and most recently in this module, we represent food systems as coupled human-natural systems. Throughout the course, we have tried to emphasize the dramatic impacts that human food production has had and continues to have on earth's natural systems. Here are some examples from previous modules:

- Changing river basins to create irrigation systems

- Exposing soils to greater rates of erosion, and stabilizing some soils against erosion

- Domestication and development of new crop types, including transgenic engineering of new crop traits in the recent past

- Contributions of agriculture to greenhouse gas emissions that are warming planet earth and leading to climate change

Different types of food systems – global, smallholder, and alternative, as we summarized in module 10.1 -- may all impact the earth's natural systems in a different way and to different degrees. You may recognize on the short list of examples above that the impacts from these changes and the creation of agroecosystems by humans may have both positive and negative aspects. For example, irrigation and crop breeding both have as objectives increasing the productive potential of crops. They may carry other unforeseen consequences, such as depletion and collapse of water resources, changes in the dietary quality of food with domestication and breeding, and greater use of herbicides in the case of Roundup-ready crops. These human system actions within the food system improve production can be seen as the initial driving arrow as part of a human-natural system coupling (Fig. 10.2.3) and generally involve management, reorganization of the ecosystem, and energy and nutrient inputs (e.g. the use of fossil fuels to create fertilizers). The natural system then responds with positive and negative impacts on productivity and other natural system processes, which can include positive and negative consequences. These consequences eventually determine the level of sustainability of the food system. The massive extent of food systems and food production globally, within different types of food systems, translates into a large effect, or leverage, on the sustainability of human societies. To promote the sustainability of food systems, we must understand how food systems as a whole affect measures of sustainability. In this unit, we will first refer to the different human system impacts on natural systems, and then allow you to practice life-cycle assessment (LCA) to compare the energy use of two food production systems in the Andes and North America.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): Measuring the Impacts of Systems in Multi-part Processes

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): Measuring the Impacts of Systems in Multi-part Processes

Life Cycle Assessments

Life cycle assessments or life cycle analyses (LCAs) are defined as “a tool to analyze the potential environmental impacts of products at all stages in their life cycle” (International Standards Organization). Analogous to the food supply chain activity you completed in module 10.1, LCAs follow products (foods and otherwise) from production, through transport and assembly steps, to the consumption or operation of the product, and in some cases even its disposal. In contrast to the supply chain descriptions in module 10.1, at each of these stages of production, transport, consumption, and disposal, LCAs keep a running total of environmental costs or impacts of the product. Common impacts that are tracked by LCAs across product life cycles are greenhouse gas emissions, water pollution impacts, and energy use. As such LCAs are a key tool in analyzing the impacts of human on natural earth surface systems within the coupled natural-human food system (Fig. 10.2.3). LCAs require some careful thinking about where to draw the boundaries of the system for considering the life cycle of a product. For example, an LCA devoted to carrots would probably include the energy required to operate the refrigerated truck used to transport the carrots but not the energy needed to make the truck. Also, many LCAs are “cradle to grave” and include both impacts of all raw materials used in production as well as disposal impacts for the product, but some do not focus on the entire life cycle and assess other segments of the lifecycle such as “cradle to farm-gate” or “cradle to plate” in the case of food products.

Life cycle analyses are an excellent way of putting into practice a geosciences "habit of mind" of using systems thinking. Because food systems are complex, we think about a way to measure its performance and then explore all the linkages in the system within that single metric or measurement parameter (see module 1.2 for a discussion of complex systems behavior). That is, we don't content ourselves with just thinking about a crop plant in a field, the entire farm field, or the highway where foods are transported; we go several levels up to measure impacts along the entire pathway or web of interacting system parts. Along the way, it is likely that we will start to think in new ways about the linkages between parts of the system, about the most important contributions to impact, or about previously hidden factors or unexpected outcomes that explain the performance of the system.

Required Reading

National Center for Appropriate Technology (NCAT): Life Cycle Assessment of Agricultural Systems [2], pp. 1-3 and figure 3 for light bulb LCA on page 9.

You'll notice that the presentation of compact fluorescent light bulbs is somewhat dated since there has now been a big move to LED light bulbs that are further reducing energy usage for lighting. We continue to feature this presentation of LCA from the NCAT because it is one of the better non-technical introductions to the subject and also relates LCA concepts to agriculture. See the resources below if you want to read more about LCAs, including a detailed PowerPoint comparing different types of light bulbs.

Additional Reading on LCAs (optional)

- Colin Sage's book, Environment, and Food, pp. 167-172, Chapter 5, Final foods and their consequences. You may remember that the first few pages of this book were assigned as a reading in module 1.1. This document may be available through your E-Reserve System.

- A PowerPoint comparison of light bulbs to complement the reading from NCAT above, H. Dillon and C. Ross: "Updating the LED Life-Cycle Assessment [14]".

- A video of a "six-minute crash course, LCA 6 minute crash course Life cycle thinking and sustainability in design [15], by Leyla Acarogluintroducing.

Using LCAs, Part One: Comparing Costs and Impacts

Using LCAs, Part One: Comparing Costs and Impacts