Lessons

Lesson 1 - Orientation and Syllabus

Lesson 1 Overview

Objectives:

For this week, you should carefully read through the syllabus and the orientation for the course.

By the end of this week:

- students will understand the course policies, course structure, different types of assignments, and their contribution to final grades;

- students will introduce themselves to the class and read introductions of classmates.

Lesson 1 Checklist

| To Read |

Carefully read the Course Orientation Lesson 1 pages. |

Use the links below to continue moving through the lesson material. |

|---|---|---|

| To Read | The Course Syllabus. | The syllabus is in Canvas — under 'Syllabus' and under 'Modules / Important Course Information' |

| To Read | Chapter 1 of Moseley, W. G., Perramond, E., Hapke, H. M., & Laris, P. (2014). An introduction to human-environment geography: local dynamics and global processes. John Wiley & Sons. | Located in the Lesson 1 module. |

| To Submit |

|

Located in the Lesson 1 module. |

Note: Please refer to the Calendar in Canvas for specific time frames and due dates.

In the following pages, you will find important information about the course structure, requirements, scheduling, and technical requirements and assistance.

Course Structure, Description and Objectives

Course Structure:

This course will be conducted entirely online. There are no set class meeting times, but you will be required to complete weekly assignments. In this course, registered students will need to navigate between several online environments.

These include:

- this site - the instructional materials in this site include weekly course materials, including course Introduction and Orientation (Week 1), the syllabus, and several other helpful supplemental pages;

- Canvas - Penn State's course management system; in this course, we'll use Canvas for our course calendar, to communicate, to access some of the readings and films, to submit assignments, and to post grades.

- Perusall [1] - an online platform that creates a shared learning environment through collaborative annotations on a PDF. This is were you will complete all reading assignments. You can find detailed instructions on how you will use Perusall for this course in the Perusall guidelines tab in the Important Course Information module for details.

Course Description:

Geography 430 examines the human use of resources and ecosystems, the multiple causes and consequences of environmental degradation, and adaptive institutional and policy arrangements as prerequisites for resilient and sustainable management and development in different parts of the world. The major objective of this course is to help geographers, earth scientists, and other professionals develop an awareness and appreciation of the multiple perspectives that can be brought to studies of human use of the environment and of the ways in which resource-management decisions are made in human society. This is a capstone course that encourages students to place their individual major and technical skills within the context of multiple approaches to environmental decision-making and management in complex and dynamic social-ecological systems. GEOG 430 is designed as a collective/social learning experience. This implies that the professor and students share responsibility for the learning process and take advantage of collective skills, insights, experiences, and efforts of each other. As in system dynamics, this requires both commitment and flexibility and the willingness to explore foreign territory. As part of this philosophy, learning consists not only of information flow from professor to student but also from student to student and student to professor.

Learning Objectives for the Course:

- Describe the changing relationships between people and their environments, the causes and consequences of environmental degradation, strategies for building a more sustainable world, and the methods and approaches that scholars have used to describe human-environment interactions.

- Explain the complexity of human-environment systems.

- Interpret, analyze and communicate effectively regarding human-environment interactions in their lives as students, professionals, and citizens (critical thinking and synthesis of ideas, map interpretation, searching for and finding and assessing academic sources and writing).

- Analyze and critique competing approaches intended to achieve environmental conservation and sustainability.

Required Course Materials

All of the materials will be embedded in the course website and posted on Canvas corresponding to the appropriate lesson. You are not required to purchase a textbook for this class.

Course Assignments and Schedule

Course Assignments:

Please read the syllabus in Canvas to ensure you understand the assignments due in this course!

Typical Schedule of Weekly Activities:

Within any given week, most assignments can be completed on your schedule. Weekly materials on Canvas unlock every Friday at midnight and reading assignments will be due the next Sunday at midnight, giving you 10 days to complete them. Please check Canvas for specific due dates and announcements.

Topics by Week:

- Lesson 1 - Introductions

- Lesson 2 - Global Environmental Change and Planetary Boundaries

- Lesson 3 - Complex Social-Ecological Systems

- Lesson 4 - Environmental Governance

- Lesson 5 - Environmental Justice

- Lesson 6 - The Food-Energy-Water Nexus and Environmental Impacts of Agriculture

- Lesson 7 - Food (Food Security, Food Sovereignty, and Agroecology)

- Lesson 8 - Energy

- Lesson 9 - Water

- Lesson 10 - Biodiversity Conservation

- Lesson 11 - Land Use Change

- Lesson 12 - Climate Change

- Week 13 to 15 - Course Wrap Up

Course Communications

Meaningful interactions among students and instructors are the hallmark of a successful online class. Canvas supports several types of communication, as described below. Registered students have Penn State email accounts (<Access Account ID>@psu.edu) that they need to monitor for any official communications that come from the University or from the Penn State World Campus.

Announcements

These are messages from your instructor that contain important information. Current announcements can be accessed through the Announcements link in Canvas. Announcements may highlight assignment due dates, changes to due dates, tips for how to do well on future assignments, and other essential course information. Announcements are made when the instructor needs to communicate with the class, including to notify the class of changes to due dates and the syllabus.

Communications from the University and from the World Campus

Occasionally, the University or the World Campus needs to communicate with students. To do so, they use the @psu.edu email address that each registered student has been given and not Canvas course email. In addition, a letter, in PDF format, that reports your final course grade will be automatically generated and sent to your @psu.edu email address. It is important that you regularly monitor your @psu.edu email account.

Setting Communication Preferences

Canvas Profile and User Settings let you control your personal information in Canvas. Take a few minutes to personalize your Canvas profile by following the instructions below. Follow the instructions on the Canvas Profile and User Settings page to customize important aspects of your profile including, but not limited to, your preferred email address(es) and text (SMS) contact method for course notifications, your time zone, and your profile picture.

You have the option to select how, when, and for what information you would like to receive notifications. This can be very helpful when keeping track of items such as discussion posts, assignment due dates, and exams. Visit the Canvas Notification Preference Support page (link is external) and follow the instructions for setting up your notification preferences.

Click on the 'Profile' link. Set your notification preferences.

To ensure that your Canvas email messages forward to your regular email account immediately, check the "Notify me right away" option (the checkmark) for each item under "Conversations" in Notification Preferences.

In the Time Zone drop-down menu, select a time zone for your course.

Consider downloading the Canvas App!

Academic Integrity

There has been a troubling increase in the number of cases of academic integrity violations, which span from honest mistakes to cases where students know the behavior is "copying" or purchasing work but still do it anyway.

All of the following are forms of academic integrity violations:

- copying and pasting without quotations

- failing to cite the source of your ideas

- copying and pasting into an online "paraphrasing tool"

- presenting someone else's material as your own

- using someone else's material from a study help site

- purchasing assignments or essays

- seeking or sharing information about the questions or answers on a quiz or exam

- other forms of cheating or dishonesty

Throughout the course, you will be regularly writing and submitting written assignments. Every element of a submission should be either (1) your original work, or (2) a properly cited idea of somebody else's. If you want to mention somebody else's idea in your work, you should follow an established set of rules for doing so. In this class, we use the APA citation style for all citations done in all assignments. More information can be found in the 'Quick Guide to Citations' in the 'Resources' menu. Be aware that the material you submit for this course will be compared with online material using tools like Turnitin.

In terms of quizzes, you must not have in your possession any preliminary information about the specific quiz questions or correct/incorrect answers to them. Yes, they are open-book quizzes, but the only things you can refer to is raw course materials and your own notes about them. Sharing answers with classmates or seeking answers on websites such as Course Hero is an intentional violation of academic integrity.

Penn State does not exempt you from consequences even when the violation was done without sufficient knowledge ("honest mistakes"). So, please make yourself aware of what constitutes a breach of academic integrity.

Please have a look at Penn State resources (Undergrad Advising Handbook [2] and a web page from the College of Earth and Mineral Sciences [3]) to see what academic integrity is and what consequences it might bring when breached.

Information to Avoid Common Mistakes

- Please use both (1) an in-text citation and (2) an end-of-the-document citation (a.k.a. reference list, works cited list) per one work cited. For full credit, you must use BOTH in-text citations and a reference list at the end of your assignments.

- When you are borrowing somebody else's idea in a word-for-word manner ("direct quotes"), use quotation marks along with an in-text citation. Failing to do so constitutes a breach of academic integrity.

Example:

As the heroine of Little Women notes, Christmas won't be Christmas without any presents.

(Wrong)

As the heroine of Little Women notes, "Christmas won't be Christmas without any presents" (Alcott, 1868, pg. #).

(Correct)

Citation (end-of-the-document) information that frequently gets left out

In this course, we seek to provide a learning experience to practice proper citing of other people's works. Some websites, for example, deliberately omit some essential citation information. It is up to you to make sure that you provide complete citation information in your submissions of weekly questions and reactions, current event discussions, and the final essay.

Typically, the citation on a website lacks the following information about the cited material you need to fill in for your assignments:

For Articles:

- Full journal name - it is NOT the same as the name of the web database service. No Science Directs or Wileys, please.

- Journal volume and issue number

For Books and Book Chapters

- Full publisher information (e.g., city of publication)

- A book chapter citation should include both (a) the title of the whole book, and (b) the title of the specific chapter you are borrowing ideas from

Web-based, non-print resources

- Add a web address when it is an exclusively web-based resource (e.g., YouTube video clip).

An example of a citation of a journal article:

In the below image, the first (wrong) one is a Google Scholar citation copy and pasted without any revision. The second (correct) one is still a Google Scholar citation, but I added missing information by doing an additional search. This example is meant to show that you MAY use Google Scholar or another citation generator, BUT more often than not, you need to ADD to or EDIT your citation generator result to have a complete citation.

Resources for Research and Citations

The purpose of this section is to introduce you to scholastic research and proper APA citation. You will be expected to know how to find academic papers and correctly cite them over the span of this course. Links provided below are example tutorials for your reference. Please go through this material now to familiarize yourself with the content.

Video Guides to APA Citation (begins at 4:10):

Video Guides to Scholastic Research:

Helpful Hint:

If you are not familiar with the Penn State University Libraries website [6], I strongly encourage you to explore this extremely valuable website to learn about other research resources available to you as a student. The Penn State University Libraries website offers additional resources, in addition to citation help, under their 'How To' section. Refer to this page for more information on citations, scholastic research skills, and tutorials.

How to Succeed in GEOG 430

Keep these tips in mind when preparing to be successful in an online course:

Treat online learning as you would a face-to-face class

You should devote at least the same amount of time to your online courses as you would to attending lectures on campus and completing assignments. Other good study habits, such as attending class (logging on) regularly and taking notes, are as important in an online course as in a lecture hall.

Intentionally schedule your time

You should devote 10-12 hours weekly to completing lesson readings and assignments. Your learning will be most effective when you engage with the course daily.

Engage, Engage, Engage

Take every opportunity to interact with the content, the instructor, and your classmates by completing assignments and participating in discussion forums and group activities!

Be organized and keep up

Keep in sync with what is happening in the course and stay on top of deadlines and upcoming assignments. If you fall behind, it can be difficult to catch up.

Ask for help

Ask for guidance when needed. Email the instructor directly through Canvas.

Other Resources

The links below will connect you with other resources to help support your successful online learning experience:

-

Tips for Being a Successful World Campus Student [7]

This website links to many resources on everything from taking notes online to managing your time effectively. Please note that you must be a World Campus student to receive some of the support services mentioned on this website.

-

Penn State World Campus Technology Resources [8]

This website provides resources to help you learn to use technology, access Penn State tools, and purchase and download software.

-

Penn State World Campus Blog [9]

This blog features posts by Penn State staff and students on a variety of topics relevant to online learning. Learn from online students, alumni, and staff members about how you can get the most out of your online course experience.

-

Penn State iStudy for Success! [10]

The iStudy online learning tutorials are free and available to all Penn State students. They cover a broad range of topics including online learning readiness, time management, stress management, and statistics - among many others. Check out the extensive list of topics for yourself to see what topics may be of most use to you!

-

LinkedIn Learning at Penn State [11]

This website provides access to an extensive free online training library, with tutorials on everything from creating presentations to using mobile apps for education. There is a wealth of information here - all provided free of charge to Penn State faculty, staff, and currently enrolled students.

Week 1 Summary and Tasks

Summary

We’ll begin this semester with the first chapter from one of the leading Human-Environment Geography textbooks. This chapter is meant to make sure we are all on the same page. It offers a great introduction to some of the major themes we will encounter during the semester and will help you to understand what Human-Environment Geography is and how it might relate to some of the more specific issues we talk about in this course.

Tasks for this week:

- Complete the online material for Lesson 1 (You have reached the end of the mateiral for Lesson 1, please see Canvas for the reading and assignments).

- Please check the Lesson 1 Overview for a full list of tasks.

Please refer to the Calendar in Canvas for specific time frames and due dates.

Feel free to start reading matierial in Lesson 2 in order to get a head start for next week....

Lesson 2 - Global Environmental Change and Planetary Boundaries

The links below provide an outline of the material for this lesson. Be sure to carefully read through the entire lesson before returning to Canvas to submit your assignments.

Lesson 2 Overview

Please make sure that you have completed the Course Orientation [12] before going any further. The course orientation will introduce you to the instructor for the course, all the steps you need to take in order to be up to speed on the logistics of the course, and more. You need to be familiar with the course expectations and deadlines before moving on with the material.

Global Environmental Change and Planetary Boundaries:

We start the course this week by thinking about the major environmental problems facing our planet and the historical development of our thinking about the factors that drive global environmental degradation and change. You will start by reading about Thomas Malthus and his theories about overpopulation. You will then read about ideas that counter this argument, including arguments that consumption and technological innovation are equally important to how many people and environment or the planet can support. This material will set you up to engage critically with the Course Material for the week.

Consider these questions as you go through the material for this week as well as when completing your assignment:

- How many people is too many?

-

Have we exceeded the tipping point of global environmental change and can we ever revert back to previous environmental conditions?

-

Are socio-economic disparities the main contributing factor to overpopulation issues? Or are there other factors we need to consider?

Lesson 2 Checklist

| To Read | Read the Lesson 2 course content. | Use the links below to continue moving through the lesson material. |

|---|---|---|

| To Read | Pearce, F. (2018) Is the way we think about overpopulation racist? The Guardian Newspaper. | https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2018/mar/19/overpopulation-cities-environment-developing-world-racist-paul-ehrlich [13] |

| To Read | Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, Å., Chapin Iii, F. S., Lambin, E. F., . . . Foley, J. A. (2009). A safe operating space for humanity. Nature, 461, 472. doi:10.1038/461472a. | A link to the reading is provided in the Lesson 2 module. |

| To Watch | FILM: Breaking Boundaries: The Science of Our Planet | A link to the film is provided in the Lesson 2 module. |

| To Submit |

See Canvas, course announcements. |

Note: Please refer to the Calendar in Canvas for specific time frames and due dates.

Introduction to Malthus, IPAT and Overpopulation

Malthusian Theory

Thomas Malthus was an English doctor and philosopher, born in England in 1766. His “An Essay on the Principle of Population” [14] proposed that population growth eventually will place catastrophic pressure on resource use - leading to famines, conflict, and other stress. Malthus suggested that population pressures lead to resource overuse, famine and misery, in particular, because exponential population growth outstrips food production. He argued that famine and misery in turn lead to vice (such as theft).

Driven by some of the pressing issues of his day, Malthus was particularly interested in connecting the predicament of England’s poor to these issues of resources use and proposed imposing restrictions on the poor, suggesting that the poor practice sexual abstinence. Malthus took issue with England’s Poor Laws (a kind of welfare system for those unable to work). He argued that supporting the poor with social welfare only postponed the inevitable famine and conflict and placed undue pressure on the rest of society. He argued that the laws (social security) simply exacerbate the predicament of the poor by enabling the population to increase even more and requiring even more food to feed even more poor people. He argued that the poor should be left to starve to prevent environmental catastrophe.

Excerpts from An Essay on the Principles of Population, Chapter 1:

I.14

I think I may fairly make two postulata.

First, That food is necessary to the existence of man.

Secondly, That the passion between the sexes is necessary and will remain nearly in its present state.

I.17

Assuming then, my postulata as granted, I say, that the power of population is indefinitely greater than the power in the earth to produce subsistence for man.

I.18

Population, when unchecked, increases in a geometrical ratio. Subsistence increases only in an arithmetical ratio. A slight acquaintance with numbers will shew the immensity of the first power in comparison of the second.

I.19

By that law of our nature which makes food necessary to the life of man, the effects of these two unequal powers must be kept equal.

I.22

This natural inequality of the two powers of population, and of production in the earth, and that great law of our nature which must constantly keep their effects equal, form the great difficulty that to me appears insurmountable in the way to the perfectibility of society. All other arguments are of slight and subordinate consideration in comparison of this. I see no way by which man can escape from the weight of this law which pervades all animated nature. No fancied equality, no agrarian regulations in their utmost extent, could remove the pressure of it even for a single century. And it appears, therefore, to be decisive against the possible existence of a society, all the members of which, should live in ease, happiness, and comparative leisure; and feel no anxiety about providing the means of subsistence for themselves and families.

Excerpts from Chapter 5:

V.1

The positive check to population, by which I mean, the check that represses an increase which is already begun, is confined chiefly, though not perhaps solely, to the lowest orders of society.

V.3

To remedy the frequent distresses of the common people, the poor-laws of England have been instituted; but it is to be feared, that though they may have alleviated a little the intensity of individual misfortune, they have spread the general evil over a much larger surface. It is a subject often started in conversation and mentioned always as a matter of great surprise, that notwithstanding the immense sum that is annually collected for the poor in England, there is still so much distress among them….

V.10

The poor-laws of England tend to depress the general condition of the poor in these two ways. Their first obvious tendency is to increase population without increasing the food for its support. A poor man may marry with little or no prospect of being able to support a family in independence. They may be said therefore in some measure to create the poor which they maintain; and as the provisions of the country must, in consequence of the increased population, be distributed to every man in smaller proportions, it is evident that the labour of those who are not supported by parish assistance, will purchase a smaller quantity of provisions than before, and consequently more of them must be driven to ask for support.

V.27

Notwithstanding, then, the institution of the poor-laws in England, I think it will be allowed, that considering the state of the lower classes altogether, both in the towns and in the country, the distresses which they suffer from the want of proper and sufficient food, from hard labour and unwholesome habitations, must operate as a constant check to incipient population.

V.28

To these two great checks to population, in all long occupied countries, which I have called the preventive and the positive checks, may be added vicious customs with respect to women, great cities, unwholesome manufactures, luxury, pestilence, and war.

Neo-Malthusian Thought and Arguments against Overpopulation

Overpopulation is the idea that there are not enough resources on the earth to sustain the earth’s population. Key to this idea is that there are certain human needs that must be filled, and that there are finite resources to fulfill these needs. You might notice that many of the ideas and language Malthus uses resonates with discussions of population, food, and poverty heard in the press today. Malthus’ ideas gained renewed interest in the 1960s and 1970s with the publication of Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb which revisited Malthus’ prediction that overpopulation would outpace food production, resulting in catastrophe. The ideas presented in these works conceive of resources as finite. This viewpoint begets discussions of resource scarcity, as it assumes that there are limits to the capacity of nature to produce or supply resources. .

Many scholars have taken issue with these ideas, in particular pointing out that human needs can be met by multiple forms, that needs can be a product of social pressures (do you need Doritos to satisfy your hunger? or an iPhone to have human interaction?), and human ingenuity and technological fixes have helped us adapt ways to meet our needs. Humans are not just parasites on the natural environment. This mindset fails to account for the ways humans modify the environment to increase production. Overpopulation arguments tend to place blame on the poor for having too many babies and not consider over consumption by wealthy that are fueled by artifact colonial regime structures.

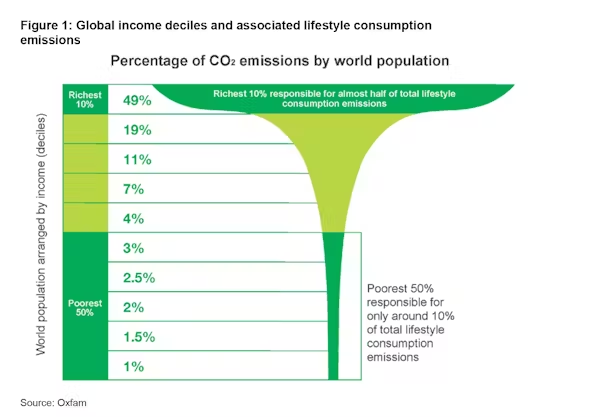

The Impact-Population Affluence-Technology (IPAT) equation is used to highlight that it is not just population that matters, but also, affluence or consumption and technology. The equation identifies three factors which contribute to environmental impacts (I): population (P), affluence / consumption (A), and technology (T). Typically, the equation is expressed as seen in the image below.

Overpopulation:

Watch this video (6 min 40 sec) to better understand population growth, changing birth rates, demographic transitions and poverty (the content might be on your quiz this week).

When we think about population we also need to think about consumption.

OPTIONAL ADDITIONAL MATERIAL:

- Peter Menzel's photo journal "Hungry Planet Family Food Portraits [16]" is a great visual documentation of how important consumption (A) is in therm of environmental impacts.

- Eric Holt-Gimenez's article "We Already Grow Enough Food For 10 Billion People -- and Still Can't End Hunger [17]" is a good start to thinking about the "doubling food production by 2050" discourse.

- The Population Research Institute’s videos on “Overpopulation is a Myth [18]”, Episodes 1-6 may also be helpful. These videos are short, only a few minutes each.

Lesson 2 Reading

Required Reading:

Pearce, F. (2018) Is the way we think about overpopulation racist? [13] The Guardian Newspaper.

Fred Pearce is a Science journalist who writes for a diversity of news outlets. He often draws on ideas from Geography to critique mainstream media content and reporting.

Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, Å., Chapin Iii, F. S., Lambin, E. F., . . . Foley, J. A. (2009). A safe operating space for humanity. Nature, 461, 472. doi:10.1038/461472a.

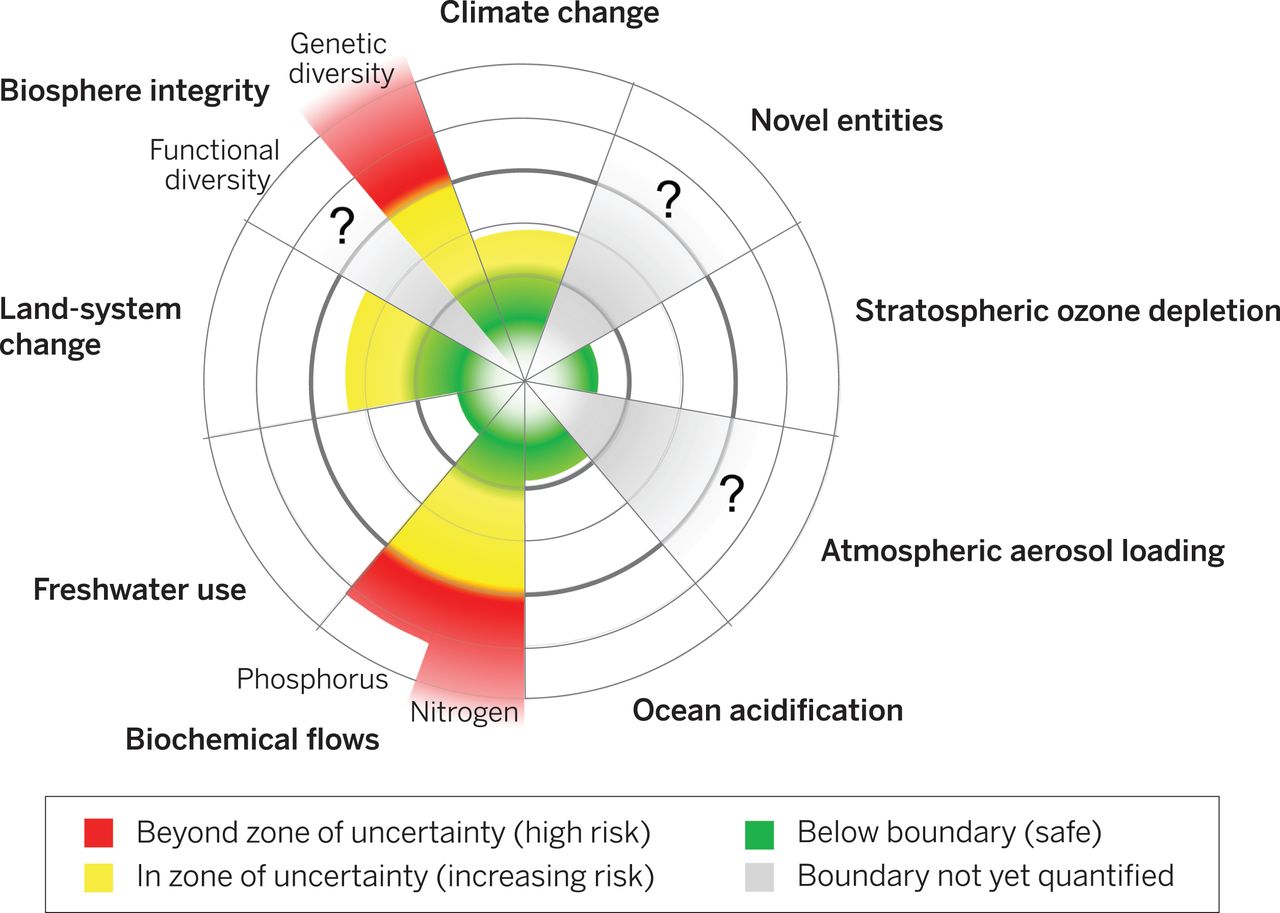

Johan Rockström and colleagues in 2009 designed a framework to determine critical planetary boundaries for 9 systems. Rockström’s research is very important because it helps us (as humanity) understand in which boundaries pose the greatest threat and where we should focus our mitigation efforts. Climate is already outside the ranges of the Holocene as we have now moved into the era of the Anthropocene. An important conclusion he drew is that the three biggest threats to our planet are the anthropogenic influences in Biodiversity Loss, Nitrogen cycle, and climate change. Human activities now convert more N2 from the atmosphere into reactive forms than all of the Earth's terrestrial processes combined. Rockström set limits to how much influence we can have in each system and both Biodiversity Loss and the Nitrogen Cycle have exceeded those limits already. Nitrogen flow should be reduced to 25% of its current value. Species are becoming extinct at a rate that has not been seen since the last global mass-extinction, with a loss of 2/3rd of mammalian animals since 2016, and 30% of all species threatened with extinction. Climate change is still within a manageable limit, but it is expected to increase exponentially towards that limit due to a wide variety of factors over the next few decades. Although Rockström’s research is very helpful, it is hard to determine the accuracy of the information due to the complex interconnectedness of systems with each other. Many of the systems are reaching what he refers to as “tipping” points. These "tipping" points are considered the point of no return for ensuring these systems stay in a balanced state such as the Holocene conditions that we have observed for the past 10,000 years. This research is important to educate the general public as it provides a great overview of the current state of our world, where it is suffering the most, and where we should focus our mitigative efforts for the future.

NOTE: A link to the Rockström reading is located in the Week 2 module in Canvas.

Film: Breaking Boundaries: The Science of Our Planet

Required Film:

Breaking Boundaries: The Science of Our Planet. 2021. Director Jonathan Clay

David Attenborough with scientist Johan Rockström and others who work on Planetary Boundaries examine Earth's biodiversity collapse and how this crisis can still be averted.

The film is currently available on Netflix (with CC) or on Dailymotion: https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x8h1bck [19]

Lesson 3 - Complex Social-Ecological Systems

The links below provide an outline of the material for this lesson. Be sure to carefully read through the entire lesson before returning to Canvas to submit your assignments.

Lesson 3 Overview

Complex Social-Ecological Systems:

As you work through this section, make sure you understand the different terms used well enough to use them correctly in your own thinking and writing (feedbacks, system state transition, thresholds, legacy, telecoupling, vulnerability, resilience, and adaptation). Can you identify examples of these outside of the course content?

More broadly, consider these questions as you go through the material for this week as well as when completing your assignment:

- Do we ever consider the long term effects of our actions in regards to the environment?

- How connected are our lives with the health state of the ecosystems?

- Have we reached the threshold of ecosystem resilience? Or have we ventured into the territory of irreversible damage?

Lesson 3 Checklist

| To Read |

Read the Lesson 3 course content. |

Use the links below to continue moving through the lesson material. |

|---|---|---|

| To Read | Reading: Liu, J., Dietz, T., Carpenter, S.R., Alberti, M., Folke, C., Moran, E., Pell, A.N., Deadman, P., Kratz, T., Lubchenco, J. and Ostrom, E., (2007). Complexity of coupled human and natural systems. Science 317 (5844): 1513-1516. | Located in the Lesson 3 module. |

| To Watch | Films: Angry Inuk and Sustainability in a Tele-coupled World | Links to the films are provided in the Lesson 3 module. |

| To Submit | See Canvas, course announcements. |

Note: Please refer to the Calendar in Canvas for specific time frames and due dates.

Social Ecological Systems, Key Definitions

Complex Social-Ecological Systems:

Complex Social-Ecological Systems is an important way of thinking about Human-Environment interactions, one which many Geographers use in their work. While Complex Social-Ecological Systems approaches are used by researchers in many fields (such as Sustainability Science, Ecology, Environmental Science, and Human Ecology), Geographers have made a central contribution to the theory and methods behind this approach. Complex Social-Ecological Systems also get called Human-Environment Systems, Adaptive Systems and Coupled Human-Natural Systems. They include interlinked "social" systems and "ecological" or "natural" systems. As you will learn in the section, the different components of these systems are complex, integrated systems composed of human society, economy, and a biological ecology.

© Penn State University is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 [21]

Positive and Negative Feed-backs:

Feedbacks refer to both an initial action and the resulting environmental reaction in a system. Positive feedbacks increase the magnitude of impact (environmental reaction) of the initial action, destabilizing the system. Melting ice [22] is an example of a positive feedback loop in the environment. On the other hand, negative feedbacks decrease the magnitude of impact (environmental reaction) of the initial action, stabilizing the system. The Carbon Cycle [23] is an example of a negative feedback loop in the environment.

© Penn State University is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 [21]

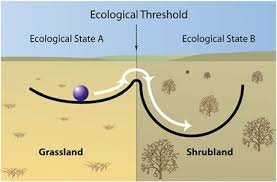

System State Transition:

System State Transition (also called Regime Shifts) are persistent changes in the structure and function of a system. System state transitions involve changes in both the composition of the system, but also the ways components of systems interact with each other. They are often perceivable to an untrained observed, such as a switch from grassland to forest or vise versa.

Threshold:

A threshold is a transitional point in one or more key factors or variables that leads to a switch between alternative system states that can be spatial (shifts through space) and temporal (shifts through time). Once a threshold in a given variable is reached, a system state transition is more likely or even unavoidable. In the example of a system state transitions between grasslands and forest there could be a threshold in the amount of precipitation, the frequency of fire or the magnitude of livestock grazing.

Legacy:

Legacy is the inheritance from anthropogenically induced change to an environmental system. Legacy effects are environmental conditions that result from past human disturbances such as land use and land cover change, fire regime, water diversions, and introduction of non-native species. Legacy effects are important because when we study how a new disturbance or change will impact a system we need to take into consideration the fact that the system may already be undergoing change from a past, sometimes unknown or unseen disturbance.

Resilience:

Resilience is the capability to retain similar structures and functioning after disturbances for continuous development (Lui et al. 2007). The term "Resilience" was first introduced to ecology by C. S. Holling (1973) and defined it as the amount of disturbance that an ecosystem could withstand without changing structure (or going through a system state transition). Other ecologists have defined it as the amount of time needed for an ecosystem to return to a stable state following a disturbance. Resilience of a system can be impacted in positive and negative ways by both human and natural component of social-ecological systems. Human intervention can play a key role in maintaining resilience.

Vulnerability

There is little agreement around the exact definition or measurement of the concept of “vulnerability”. In the context of social-ecological systems research vulnerability includes the potential for adverse consequences to occur in response to different events. For some "vulnerability" is similar to "risk". “Risk” is a combination of the magnitude of impact or adverse outcomes due to an event, as well as the likelihood that those outcomes will occur. Both the likelihood or an even and the magnitude of impact are shaped by both social and environmental factors.

Adaptation / Adaptive Capacity

Adaptive systems are able to re-configure without significant changes in crucial functions or declines in ecosystem services. Systems that are not adaptive have constrained options during periods of reorganization and renewal. Adaptive capacity in ecological systems is associated with all types of diversity (genetic, biological, and landscape) and to institutions, knowledge and networks for learning in social systems (The Resilience Alliance [25]).

Telecoupling:

Socioeconomic and environmental interactions between coupled human and natural systems over distances (Liu et al. 2013 [26]). Jack Lui explained “Telecoupling is about connecting both human and natural systems across boundaries. There are new and faster ways of connecting the whole planet -- from big events like earthquakes and floods to tourism, trade, migration, pollution, climate change, flows of information and financial capital, and invasion of animal and plant species.” The prefix “tele” means “at a distance” Liu developed the concept as a way to express one of the often-overwhelming consequences of globalization. Today increased trade, transportation, human movement and global scale environmental change means that an event or phenomenon in one corner of the world can have an impact far away.

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License [28].

Additional Information:

-

The Resilience Alliance [29] is a great supplemental resource for more in-depth definitions of the terms and additional concepts listed above.

Lesson 3 Reading

Liu, J., Dietz, T., Carpenter, S.R., Alberti, M., Folke, C., Moran, E., Pell, A.N., Deadman, P., Kratz, T., Lubchenco, J. and Ostrom, E., (2007). Complexity of coupled human and natural systems. Science 317 (5844): 1513-1516.

Liu and collaborators discuss the different aspects that define coupled human and natural systems (CHANS) and exemplifies these aspects through six case studies. These case studies help relate how the parts of these systems can be applied to our world around us. CHANS are a relatively new way of studying the connection between humans and the environment because there is rarely crossover between social sciences and ecology. This expanse into interdisciplinary research between the two fields has provided us an understanding of how our actions as humans can have impacts on ecological systems at all scales. Feedback loops and reciprocal effects go hand in hand to describe the effect of humans on environment and the resulting responses of humans to those environmental changes. Spatial and temporal thresholds mark substantial changes as humans exploit the resources of ecological systems, disrupting, and therefore shifting, the natural states of these systems. Unlike when we talked about planetary boundaries last week, CHANS does not necessarily mean there will be detrimental effects to an ecosystem. The resilience capability of an ecological system can help retain their structure and function after experiencing some type of disturbance, however human impact can impede resilience. While reading this paper, reflect on the questions posed in the overview to help guide your critical thinking.

Note: A link to the reading is located in the Lesson 3 module in Canvas.

Film: Angry Inuk

Required Film:

Arnaquq-Baril, A. (Producer and Writer), with Cross, D. and Moore, B. (Executive Producers). (2016) Angry Inuk. Produced by Unikkaat Studios Inc., in co-production with the National Film Board of Canada, in association with EyeSteelFilm.

Angry Inuk is a documentary made by Inuk woman and film maker Alethea Arnaquq-Baril. Thoughout the film, Arnaquq-Baril illustrates how seal hunting is an integral part of both the Inuk’s economy and way of life. She critiques the tactics of Greenpeace in implementing a ban on seal skin products. Arnaquq-Baril explains how the European ban on seal skins is hurting the Inuk economy, despite exemptions for seal skin products from indigenous subsistence hunting. She then demonstrates how the Inuk are using social media to sway public opinion and protest the European seal skin ban. Arnaquq-Baril also notes that Arctic seal populations are increasing.

As you watch the film, think about what the Inuit Social-Ecological system and the ways the different aspects of Complex Social-Ecological Systems and concepts from the reading this week, apply to this system.

The film is available for free on YOUTUBE: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=thzMNIBkqJM [30]

Lesson 4 - Governance

The links below provide an outline of the material for this lesson. Be sure to carefully read through the entire lesson before returning to Canvas to submit your assignments.

Lesson 4 Overview

Governance of Resources:

This week we will examine theories and approaches to study how resources (especially natural resource) are governed. Governance refers to the norms, institutions and processes that determine how power and responsibilities over resources are exercised, how decisions are made, and how different people participate in these processes. In Geography we pay particular attention to how different groups (and especially marginalized groups) participate in and benefit from the management of resources. The effectiveness and equity of governance processes critically determine both the extent to which ecosystems contribute to human well being and the sustainability of use.

Consider these questions as you go through the material for this week as well as when completing your assignment:

- Whose responsibility is it to manage local resources? Global resources?

- What are the socio-economic and socio-ecologic implications of resource extraction?

- When is it beneficial for a government or private company to control a resource? When is it not beneficial?

Lesson 4 Checklist

| To Read |

Read the Lesson 4 course content. |

Use the links below to continue moving through the lesson material. |

|---|---|---|

| To Read | Reading: Ostrom, E. (2009). A General Framework for Analyzing the Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems. Science, 325(5939): 419–22. | A link to the reading is located in the Lesson 4 module. |

| To Read | Reading: Watts, M. (2004). Resource curse? Governmentality, oil and power in the Niger Delta, Nigeria. Geopolitics, 9(1), 50-80. | A link to the reading is provided in the Lesson 4 module. |

| To Submit | See Canvas, course announcements. |

Note: Please refer to the Calendar in Canvas for specific time frames and due dates.

Resource Governance, Tragedy of the Commons and Ostrom

Resource Governance:

Governance refers to the norms, institutions and processes that determine how power and responsibilities over resources are exercised, how decisions are made, and how different people participate in these processes. In Geography we pay particular attention to how different groups (and especially marginalized groups) participate in and benefit from the management of resources. The effectiveness and equity of governance processes critically determine both the extent to which ecosystems contribute to human well being and the sustainability of use.

Garret Hardin and the Tragedy of the Commons:

Dr. Garret Hardin (1915-2003) was a famous ecologist and microbiologist at University of California - Santa Barbara (UCSB). Hardin's interdisciplinary work in human ecology and biology is considered to be part of the foundation of modern ecology. This interdisciplinary approach allowed him to develop ideas on humanity's relationship with nature and human population growth. He saw humans as a specialized entity within the biologic system that allowed it to grow nearly unchecked as a result. Hardin was a strong proponent of human population control and resource management, supporting controversial ideas such as sterilization and anti-immigration policies. He was aware that humanities resources are finite, exhausted even more with unchecked population growth, thus he justified his support of these controversial ideas based on this rationale.

Below are a few select quotes from Dr. Hardin:

“A finite world can support only a finite population; therefore, population growth must eventually equal zero.”

“It is clear that we will greatly increase human misery if we do not, during the immediate future, assume that the world available to the terrestrial human population is finite.”

“A community that renounces war as a means of settling international disputes still cannot survive without that discriminating form of altruism we call patriotism. It must defend the integrity of its borders or succumb into chaos."

“In a competitive world of limited resources, total freedom of individual action is intolerable.”

“We summarize the situation by saying: ‘There is a shortage of food.’ Why don’t we say, ‘There is a longage of people’?”

“To survive indefinitely in good shape a nation must take as its advisers people who can see farther than investment bankers.”

Hardin is most notably known for his published 1968 Science magazine essay, "The Tragedy of the Commons," cautions about finite resources and that humanity must accept and adapt to the looming future of limited resources. In his essay, Hardin observes that rational self-interest does not benefit society as a whole. Self-interested individuals who share a common-pool resource perceive the full benefits of harvesting the resource, but the negative consequences of reckless use of the commons is distributed among all users. As a result, everyone tries to consume as much as they can, thus depleting the commons. The most common example of this was provided by the British political economist William Forster Lloyd in 1832. Lloyd had made an observation that cattle grazing on a common space land were more malnourished than their counterparts which grazed on privately owned land. Following Hardin's rationale, as each farmer tries to add more cattle to capitalize on the free grazing space that space will degrade and deplete in faster than normal conditions, thus destroying the free grazing space for everyone else. Hardin prescribes either separating the resource into private allotments or putting in place restrictions and penalties to manage common-pool resources. This, along with the ideas brought forth from this essay, have been broadly accepted as an integral contribution to ecology, population theory, economics, and political science research of today.

Elinor Ostrom:

Elinor Ostrom (1933-2012) was and remains to be the first woman to win a Nobel prize in Economics for her work on sustainability and commons management. Unlike Hardin's thoughts on the impending doom of commons, Ostrom believed that the future of commons were not as bleak. Her research involved studying real world cases of commons uses, conservation, and sustainability. She found through her work, and often argued with Hardin over, that if commons resource management were to be left up to a local community, they would work together to conserve that resource. Her belief in a governmental or privatized entity being able to adequately manage common resources was limited. Overall, Ostrom felt that a polycentrist approach was the best. Although much of her research was based around localized efforts, she was also a strong advocate for global issues like climate change and sustainable practices. Ostrom encouraged economists to consider ecologic ideology in order to promote sustainable practices and mitigate climate change for the future.

Below are a few select quotes from Dr. Ostrom:

“As long as a single center has a monopoly on the use of coercion, one has a state rather than a self-governed society.”

“But until a theoretical explanation -based on human choice – for self-organized and self-governed enterprises is fully developed and accepted, major policy decisions will continue to be undertaken with a presumption that individuals cannot organize themselves and always need to be organized by external authorities.”

"Little by little, bit by bit, family by family, so much good can be done on so many levels."

“There is no reason to believe that bureaucrats and politicians, no matter how well meaning, are better at solving problems than the people on the spot, who have the strongest incentive to get the solution right.”

"Bureaucrats sometimes do not have the correct information, while citizens and users of resources do."

Optional Readings:

Resources Curse

The term Resources Curse (also referred to as the paradox of plenty) first entered debates about development and economics in the 1990s. In their paper titled "Natural Resource Abundance and Economic Growth [36]", Sachs and Warner (1995) defined this term by stating that countries with an abundance of natural resources, tend to have less economic growth, less democracy, and worse development outcomes than countries with fewer natural resources. Although it may seem intuitive that positive economic development would result from the discovery of resources within a country, it can have the opposite effect. It has been observed that there are higher rates of conflict and hegemonic practices coupled with economic instability and stunting in resource-rich countries.

Many socio-economic challenges may arise for a country as a result of resource abundance. One such challenge is the phenomena called Dutch Disease. This phenomena refers to an instance that happened in the 1960's in the Netherlands, where a discovery of a natural gas field caused temporary boom to the industry and thus created issues for other sectors of the economy. Specifically, this can be defined as a situation where other sectors within a countries economy are negatively impacted by the growth in national income from natural resource extraction. An example of this in the United States would be the oil boom that started in 2006 in the Bakken formation in western North Dakota. Ross (2015) paper titled, "What Have We Learned about the Resource Curse? [37]", argued that out of all the resource industries, petroleum/oil was the most damaging as it promotes civil instability between classes, oversight incentives (i.e. corruption), and authoritarian regimes. This is apparent in developing, third-world countries, such as equatorial Africa, where governments are more likely to be unstable and there are large disparities between social classes.

Lesson 4 Reading

As you read this week, make sure you pay attention to and learn how to define the following: Governance, Common Pool Resource, Governmentality, Resource Curse.

Ostrom, E. (2009). A General Framework for Analyzing the Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems. Science, 325(5939): 419–22.

This is one of Ostrom's most recent pieces of writing and clearly summarizes the factors needed for sustainable governance of common pool resources and the autonomous organization of resource users to maintain their resources. In this paper, she highlights that the following factors shape the success of common pool resource governance:

- Size of resource system

- Productivity of system

- Predictability of system dynamics

- Collective-choice rules

- Resource unit mobility

- Number of users

- Leadership/entrepreneurship

- Norms/social capital

- Knowledge of SES/mental models

- Importance of resource

Watts, M. (2004). Resource curse? Governmentality, oil and power in the Niger Delta, Nigeria. Geopolitics, 9(1), 50-80.

Dr. Michael Watts, an emeritus professor at the University of California - Berkely and a highly respected Environment-Society Geographer, has written extensively on resource governance and the idea of the Resources Curse. He uses a political ecology and political economy to study the governance of oil in Nigeria and the Niger Delta region. Watts uses the oil industry in Niger Delta as a case study to highlight the ongoing governmental and industry hegemony against the citizens of the region. His conclusions parallel the conclusions Ross (2015) came to in his article by bringing attention to the political disfunction which has been caused by oil.

Dr. Watts concludes his article with this profound statement that reflects and sums up the the influence of oil globally: "Oil may indeed be a curse but its violent history – and its ability to generate conflict – can only be decoded if we are attentive to the unique qualities of oil itself” as well as institutions and existing political landscape."

NOTE: Links to the readings are located in the Lesson 4 module in Canvas.

Lesson 5 - Environmental Justice

The links below provide an outline of the material for this lesson. Be sure to carefully read through the entire lesson before returning to Canvas to submit your assignments.

Lesson 5 Overview

Environmental Justice:

This week, we will learn about Environmental Justice/ injustice, Environmental Racism, and the ways that structural racism result in exposure to and protection from environmental and health hazards. We will examine the ways that less powerful communities have unequal access to and involvement in decision-making processes around their environments and related health and well-being outcomes. We will examine case studies from New York, California, and Mississippi. Some students find the material this week challenging and even emotionally difficult; please keep an open mind while you work through the material this week!

Consider these questions as you go through the material for this week as well as when completing your assignment:

- Who gets to make decisions about human use of the environment?

- Who benefits from these decisions?

- Who bears the negative impacts?

Lesson 5 Checklist

| To Read |

Read the Lesson 5 course content. |

Use the links below to continue moving through the lesson material. |

|---|---|---|

| To Read | Pulido, L. 2000. ‘‘Rethinking Environmental Racism: White Privilege and Urban Development in Southern California.’’ Annals of the Association of American Geographers 90:12–40 | A link to the reading is located in the Lesson 5 module. |

| To Read |

Gupta, J., Liverman, D., Prodani, K., Aldunce, P., Bai, X., Broadgate, W., ... & Verburg, P. H. (2023). Earth system justice needed to identify and live within Earth system boundaries. Nature Sustainability, 6(6), 630-638. |

A link to the reading is located in the Lesson 5 module. |

| To Submit | See Canvas, course announcements. |

Note: Please refer to the Calendar in Canvas for specific time frames and due dates.

Environmental Justice

Introduction

Majora Carter grew up in the South Bronx, and in this TedTalk, she details her struggle for environmental justice where she lives. Her talk describes how marginalized neighborhoods suffer the most from flawed urban policy, and delivers some of her ideas for a way forward. Since giving this Ted Talk, Majora Carter has gone on to win an astounding array of International Awards and has been given numerous honorary degrees from prestigious Universities across the USA. Pay close attention to the causes and consequences of environmental injustice that Carter identifies.

Key Concepts in Environmental Justice:

Environmental Justice: the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.

Environmental Injustice: unequal protection from environmental and health hazards and unequal access to the decision-making process to have a healthy environment in which to live, learn, and work.

History of Environmental Justice in the USA: Struggles over unequal exposure to environmental hazards have been taking place for a very long time in societies all around the world, but the origins of environmental injustice as a concept can be traced back to 1982, when the State of North Carolina needed to clean up highly toxic waste (Polychlorinated biphenyl, or PCB, which is so dangerous to the environment and human health that the US banned it in 1979) that a company had been illegally dumping along highways across the state. After sending the perpetrators to jail, North Carolina decided to clean the highways and to relocate the toxic PCB-laden soil to a landfill, which they sited in the African American community of Afton, Warren County. The landfill was not a safe way to contain PCBs, and it represented a severe threat to the health of this community. However, African Americans have historically had very little political power in North Carolina, and it took over twenty years of lawsuits, protests, and public appeals for the state to take responsibility. In 2003, state and federal agencies detoxified the 81,500 tons of PCB-laden soil by burning it in a kiln that reached over 800 degrees. The residents' struggle in Warren County remains a powerful symbol for the environmental justice movement.

White flight: a term used to refer to the large-scale movement of white people (of various European ancestries) from neighborhoods that were increasingly racially mixed in urban centers, to more racially homogeneous suburban or exurban regions.

Redlining. Click on the link for an article describing the process of white flight in the United States. Then, take a look at how Fair Housing Center of Greater Boston [39] describes redlining:

Redlining is the practice of denying or limiting financial services to certain neighborhoods based on racial or ethnic composition without regard to the residents' qualifications or credit worthiness. The term "redlining" refers to the practice of using a red line on a map to delineate the area where financial institutions would not invest.

In the United States, from the 1930s through the 1960s, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which insured private mortgages and helped encourage home ownership, commonly used redlining in urban areas as a way to maintain segregation. The practice also served to concentrate economic resources in white neighborhoods and to concentrate harmful sources of pollution in black neighborhoods. As Ta-Nehisi Coates writes in the recent Atlantic article "The Case for Reparations" [40]:

The FHA had adopted a system of maps that rated neighborhoods according to their perceived stability. On the maps, green areas, rated “A,” indicated “in demand” neighborhoods that, as one appraiser put it, lacked “a single foreigner or Negro.” These neighborhoods were considered excellent prospects for insurance. Neighborhoods, where black people lived, were rated “D” and were usually considered ineligible for FHA backing. They were colored in red. Neither the percentage of black people living there nor their social class mattered. Black people were viewed as a contagion. Redlining went beyond FHA-backed loans and spread to the entire mortgage industry, which was already rife with racism, excluding black people from most legitimate means of obtaining a mortgage.

Today, redlining is illegal, but the wealth gap that it created remains and continues to exert a huge influence on the geography of financial investment and toxic waste sitting in the United States.

Political Ecology:

Political Ecology is another approach commonly used in Geography, especially Human-Environment Geography. Like Environmental Justice, Political Ecology pays close attention to justice and equity and the ways environmental change and environmental policy impact different people differently. The three core assumptions of Political Ecology are:

- The costs and benefits associated with environmental policy and change are unequally distributed.

- Environmental policy and change can either reinforce or reduce existing social and economic inequalities.

- Those changes in equality and power relations have political implications.

Political Ecology is covered in depth in other Geography courses at Penn State, so will not be covered in detail here. However, because it is such a central approach in Human-Environment Geography, a number of the papers you will read for this course will be written from a Political Ecology perspective.

Lesson 5 Reading

Pulido, L. (2000). Rethinking Environmental Racism: White Privilege and Urban Development in Southern California. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 90:12–40.

In her piece "Rethinking Environmental Racism: White Privilege and Urban Development in Southern California", Pulido argues that existing literature holds a “narrow understanding” of racism. She points out three specific issues that contribute to the narrow conception of racism which are: an emphasis on individual facility, role of intentionality, and an uncritical approach to scale. In the beginning of the paper, Pulido presents the question, “How did whites distance themselves from pollution and nonwhites?”, which can help to answer why nonwhites are the populations exposed to more environmental “bads” than they are “goods”. Clean air and access to parks are two examples of environmental goods and polluted air and close proximity to toxic pollutants are two examples of environmental bads. Pulido criticizes Baden and Coursey’s (1997) Six Sequential Scenarios and Conclusions. She claims that their reasoning behind stating that only two of these scenarios can be the only mechanisms to measure environmental racism is creating a mindset that in order for an action to be considered environmentally racist it must be doing so intentionally, and as we can see that is not the case all the time. Pulido's groundbreaking contribution to geography (and environmental justice studies) in this article is that she combines the mapping of racial demographics and siting of toxic facilities with spatial renderings of suburbanization and white flight to produce a more complex understanding of environmental racism as an ongoing process. Specifically, she explores different ways of understanding environmental racism, and emphasizes "white privilege" as a particularly influential form of racism that has shaped urban and suburban development in the United States.

Gupta, J., Liverman, D., Prodani, K., Aldunce, P., Bai, X., Broadgate, W., ... & Verburg, P. H. (2023). Earth system justice needed to identify and live within Earth system boundaries. Nature Sustainability, 6(6), 630-638.

You have likely heard of Environmental Jusice, and may even have covered the concept in other courses. This paper and other writing by Joyeeta Gupta and coauthors is important becuase it applies concpets of justice and enironmental justice to earth systems and planetary boundaries. They propose the concept of "Earth system justice", which refers to the concept of ensuring a fair distribution of environmental benefits, risks, and responsibilities across all people, within the planetary boundaries. They note that justice must be considered alongside ecological limits of our planet to protect the planet and its inhabitants equitably. The paper emphasizes that living within planetary boundaries must also include addressing inequalities to prevent disproportionate harm to marginalized communities and prioritize their needs when making decisions about resource allocation and environmental protection.

NOTE: A link to the reading is located in the Lesson 5 module in Canvas.

Lesson 6 - The Food-Energy-Water Nexus

The links below provide an outline of the material for this lesson. Be sure to carefully read through the entire lesson before returning to Canvas to submit your assignments.

Week 6 Overview

The Food-Energy-Water Nexus:

William Easterling, NSF assistant director for Geosciences and Professor of Geography at Penn State has commented: "Food, energy and water have long been studied independently or in pairs, but not all three at once... Now, novel ways of examining all three together are yielding important new knowledge that will help us achieve food, water and energy security even with further population growth."

This week, we will read about the FEW Nexus and the Environmental Impacts of Agriculture.

As you go through the material for this week, consider the following:

- How might thinking about food-energy-water all at the same time improve decision making around sustainability?

- What links do you see to past weeks (Planetary Boundaries, Social-Ecological Systems, Governance and Environmental Justice)?

- Does the idea food-energy-water nexus consider justice and equity adequately?

- Do you believe we can produce enough food to feed the world and reduce the environmental impacts of food production? Do you see links to Malthusian thought in this weeks material?

Week 6 Checklist

| To Read | Read the Week 6 course content. |

Use the links below to continue moving through the lesson material. |

|---|---|---|

| To Read | Leck, H., Conway, D., Bradshaw, M., & Rees, J. (2015). Tracing the water–energy–food nexus: description, theory and practice. Geography Compass, 9(8), 445-460. | A link to the reading is located in the Lesson 6 module. |

| To Read | Huntington, H. P., Schmidt, J. I., Loring, P. A., Whitney, E., Aggarwal, S., Byrd, A. G., ... & Wilber, M. (2021). Applying the food–energy–water nexus concept at the local scale. Nature Sustainability, 4(8), 672-679. | A link to the reading is located in the Lesson 6 module. |

| To Read | Stein, C., & Jaspersen, L. J. (2018). A relational framework for investigating nexus governance. The Geographical Journal (online first). | A link to the reading is located in the Lesson 6 module. |

| To Submit | See Canvas, course announcements. |

Note: Please refer to the Calendar in Canvas for specific time frames and due dates.

The FEW Nexus and Environmental Impacts of Agriculture

The Food Energy Water Nexus:

Humanity depends upon the Earth's resources to provide key resources needed for human well-being and economic growth: food, energy, and water (FEW). In the face of growing pressure on our planet (see Lesson 1 - Planetary Boundaries), decisions about where and how to produce each of these must be considered carefully. There are clear trade-offs between the three, and multiple interdependences. In the face of these challenges, it is essential that we learn to think about the production of these resources in an integrated way. Geography has long excelled at thinking about such complex issues, as you have learned over the past weeks. We must find ways to best integrate social, ecological, physical and built environments to provide all three of these resources in a sustainable and just manner. The Food-Energy-Water Nexus is a new way of looking at things, and now supported by funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF). Research publications proposing, testing and using FEW frameworks are only recently starting to emerge.

The NSF notes "Known stressors in FEW systems include governance challenges, population growth and migration, land use change, climate variability, and uneven resource distribution. The interconnections and interdependencies associated with the FEW Nexus pose research grand challenges. To meet these grand challenges, there is a critical need for research that enables new means of adapting societal use of FEW systems." (Innovations at the Nexus of Food, Energy and Water Systems (INFEWS) [41]).

As you progress through the following weeks of content in the course (Lesson 7: Food, Lesson 8: Energy and Lesson 9: Water) keep thinking about each through a FEWs Nexus lense and watching for the interconnetions between them.

Week 6 Reading

Required Reading:

Leck, H., Conway, D., Bradshaw, M., & Rees, J. (2015). Tracing the water–energy–food nexus: description, theory and practice. Geography Compass, 9(8), 445-460.

The authors examine reasons for the increase in research focused around the nexus of water, energy, and food (WEF). In so doing, they investigate why it would be difficult to achieve the type of disciplinary boundary that is typically promoted in scholastic research and consider how to initiate many of the present theories and practices that have yet to be applied in the real world. Leck et al. (2015) indicate that there are although the nexus approach has been around prior to this increase, it has been challenging to encompass the interdependent WEF relationships and thus limiting its execution and progress at all scales of implementation. The future of nexus approaches to address global environmental change is promising should the movement be able to overcome previous hurdles. As advancements in technology to learn more of the linkages of WEF at varied scales as well as promoting collaboration between state and non-state entities continues, these hurdles will become more manageable.

"Identifying winners and losers in WEF nexus decision-making and giving explicit attention to justice and equity concerns are central for nexus agendas to be socially progressive (Dupar and Oates 2012; Stringer et al. 2014)."

"As Allouche et al. (2014: 23) explain, ‘food, water and energy have never been conceptually separated in the way that experts have sought to understand them. Indeed, it may be that the WEF nexus is the (re)discovery by experts working in silos of what practicing farmers and fishers already knew’."

"...scalar considerations are central to the nexus because water, energy or food interventions are not necessarily suitable or effective at all scales."

Huntington, H. P., Schmidt, J. I., Loring, P. A., Whitney, E., Aggarwal, S., Byrd, A. G., ... & Wilber, M. (2021). Applying the food–energy–water nexus concept at the local scale. Nature Sustainability, 4(8), 672-679.

This paper presents an effort to use FEW Nexus thinking to a specific social-ecological syste / setting in rural Alaska. In doing so they demonstrate that the framework can be applied beyond the theoretical. The authors raise concern that Nexus approaches fail to cover other factors that are very important to community well-being and may in fact be even more important than food, energy and water (in this case governance and transportation). They also note that proper consideration of these additional aspects of the system further complicates analysis.

Stein, C., C. Pahl-Wostl and J. Barron (2018). "Towards a relational understanding of the water-energy-food nexus: an analysis of embeddedness and governance in the Upper Blue Nile region of Ethiopia." Environmental Science & Policy 90: 173-182.

This paper provides a case study of what the study of the Food-Energy-Water Nexus looks like in real life: here in the upper Blue Nile watershed in Ethiopia. The paper tries to move from the abstract idea of the nexus to examine the collaboration and cross-sector coordination needed to achieve integrated management of Food, Energy, and Water production. As you read this paper, try to link back to your reading on governance in past weeks; what similarities and differences do you note?

NOTE: Links to the readings are located in the Week 6 module in Canvas.

Lesson 7 - Food

The links below provide an outline of the material for this lesson. Be sure to carefully read through the entire lesson before returning to Canvas to submit your assignments.

Week 7 Overview

This week, we will explore the first item in the Food-Energy-Water nexus: Food. We will examine how food and agricultural policy shape what we eat and how we produce what we eat. Last week, we looked briefly at the ways food and agricultural systems impact our planet. This week, we will focus on the ways our food and agricultural systems impact the health and well-being of people producing food, as well as consumers.

As you work though the material for this week, consider:

- Who controls the food system, and how much say do consumers have? After this week's material, how effective do you think "voting with your wallet" is?

- What concerns you more: the environmental impacts of food production, or the societal issues (such as health and well-being of farmers), or both? Are they interrelated, and if so, how?

- What can be done to improve our food and agriculture systems? Will the cost in ill-health resulting from poor quality diet eventually motivate change?

Week 7 Checklist

| To Read |

Read the Week 7 course content. |

Use the links below to continue moving through the lesson material. |

|---|---|---|

| To Read | Graddy-Lovelace, G. (2017). The coloniality of US agricultural policy: articulating agrarian (in) justice. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 44(1), 78-99 | A link to the reading is located in the Lesson 7 module. |

| To Read | Altieri, M. and V.M. Toledo, (2011). The Agroecological Revolution of Latin America: Rescuing Nature, Securing Food Sovereignty and Empowering Peasants. Journal of Peasant Studies, 38 (3): 587–612. | A link to the reading is located in the Lesson 7 module. |

| To Watch |

Film: Banana Land: Blood, Bullets, & Poison Optional Film: King Corn |

Links to the films are located in the Lesson 7 module. |

| To Submit |

See Canvas, course announcements. |

Note: Please refer to the Calendar in Canvas for specific time frames and due dates.

Food, Agriculture, Sovereignty and Sustainability

Geography of Food and Agriculture

Food, and its production through agriculture, are core topics in Human-Environment Geography. Political Ecology evolved as a field largely to deal with problems and problem narratives around food production (for example, to counter narratives of overpopulation as a reason for degradation of agricultural land). One of the earliest scholars to use a Political Ecology approach was Michael Watts in his 1983 book "Silent violence: food, famine, and peasantry in northern Nigeria" in which he argued that famine in Nigeria was linked to colonial policies that pushed commodity production on rural farmers, making them less resilient to drought. This was followed by Blaikie and Brookfield's 1987 "Land degradation and society" which is perhaps the best known example of a Political Ecology approach. Blaikie and Brookfield examined why land management often fails to prevent soil erosion, and sought to counter the narrative that poor farmers are poor land managers, to blame for soil degradation. They demonstrated how land accumulation by (largely white) elites in Southern Rhodesia had pushed poor farmers to more marginal land with higher risk of degradation. Since the 1980s, food and agriculture has remained a central topic in Human- Environment Geography. For example, Judith Carney, Rick Schroeder, Rebecca Elmhirst, and others have worked to demonstrate how social, economic, and political change in agricultural systems has lead to increasing burden on women around the world (Canrey 1993, Schroeder 1999). Penn State's Karl Zimmerer has published extensively on the Geography of Food and Agricultural systems in South America. In his book "Changing Fortunes: Biodiversity and Peasant Livelihood in the Peruvian Andes," he pushed back against the idea that the agrobiodiversity (diversity of crops grown) of the Andes was hopelessly endangered, by highlighting contemporary practices and attitudes that act to conserved agrobiodiversity, essential to adaptation.

Human-environment geographers are attentive to the ways narratives are used to justify or promote certain policies and this includes food and agriculture policy at the international scale and national scale, including here in the USA. For example, Jarosz (2014) examined the history and narratives around food security and food sovereignty, noting that food sovereignty narratives have evolved to fill a gap left by the fact that food security narratives have failed to adequately address justice and poverty as a driver of food insecurity. This week, you will read a paper by Garret Graddy-Lovelace on the ways that US agricultural policy perpetuate injustice and inequity.

When geographers examine global value chains, food is often the commodity used to demonstrate the ways global interconnections and telecoupling impact both producers and consumers (Benson and Fischer 2007, Cook 2004, Zimmerer et al. 2018). Freidberg's (2004) "French Beans and Food Scares" documents the way food safety policies demanded by European consumers perpetuate inequality for producers in Africa. The films you will watch this week will highlight the ways food has become a commodity, and the implications for farmers and consumers' health and well-being.