Lessons

1: Energy in Transition

About this Lesson

Before we can think about where we want our energy future to take us and how public policy can help us get there, we need to understand how it got us to where we are today. This week, we'll be exploring the history of energy use, specifically focusing on how our ability to harness and utilize varying energy resources has enabled us to make advances in our societies throughout time. By examining historical trends in energy consumption and more importantly the transition from one major energy source to another (e.g. wood to coal and coal to oil and gas), we will be better equipped to understand what we might expect in the future. This is particularly important given that we are in the midst of a transition to low-carbon sources (not as rapidly as we need to, it should be noted) and policy has and will continue to play an important role in facilitating that transition. Having even a cursory sense of society's historical relationship with energy resource utilization will help to ground our discussions of the future of energy use and the role it will have in the development and evolution of our societal structures.

By the end of this lesson, you should understand:

- the different types of energy resources humans have employed throughout history, and the consequences of each;

- the link between access to energy and population growth;

- the consequences of reliance on either hard or soft energy paths;

- the concept of energy transitions and what the historical precedent of these transitions might mean for future energy resources.

What is due?

This lesson will take us one week to complete. Please refer to the corresponding module in Canvas for specific assignments, deliverables, and due dates.

Questions?

If you have questions, please feel free to post them to the "Ask a Question about the Lesson" Forum. While you are there, feel free to post your own responses if you, too, are able to help a classmate.

Earliest Energy

Earliest Energy

In order to understand where we are with our energy resources and consumption patterns today, it's worth taking a look back at how human energy use has changed over time. Most of us have trouble imagining a day without interior lighting in our homes or Internet connectivity, so imagining early humans and their most primitive of energy resources is somewhat challenging.

The Industrial Revolution and Energy Use

It really wasn't until the Industrial Revolution in the 1800s that human's ability to harness energy on a (relatively) large, efficient scale took place and truly revolutionized our ways of life and ability to perform work. Prior to that, early people relied primarily on caloric energy from the food they consumed to give the energy they needed to perform their basic tasks for survival. With the discovery of fire and the ability to burn biomass (wood, animal dung, charcoal), humans then had an important source of heat.

With the domestication of animals, humans were able to transition from a more nomadic way of life as a hunter/gatherer into a more agrarian society. Harnessing animal energy allowed early humans to grow more food more efficiently and stay in one place. It comes as no surprise that the ability to produce more food easily translated into sustained population growth. Early society was taking a different shape, thanks in large part to human's ability to utilize these energy opportunities.

As the graph above illustrates, wood remained the dominant fuel source until it was surpassed by coal powering the Industrial Revolution in the late 1880s. Throughout wood's reign as the world's primary fuel source, overall energy consumption grew steadily, but remained quite low compared to the levels that would develop in the wake of the Industrial Revolution. Coal was our primary energy source until around the late 1940s when it was overtaken by oil, which remains out main energy source.

This explosion in energy consumption changed human history in almost every way. The ability to mass produce goods and a focus on a consumption-based economy were huge paradigm shifts from previous subsistence societies. The migration of people from rural areas to cities for work led to issues associated with poor sanitation and working conditions. But many of the modern conveniences on which we've become reliant were born out of this era.

Energy Transitions

Energy Transitions

Vaclav Smil defines an energy transition as, "the time that elapses between the introduction of a new primary energy source (coal, oil, nuclear electricity, wind captured by large turbines) and its rise to claiming a substantial share of the overall market" (2010).

If we explore historical energy transitions, we will see that they all have one thing in common - they tend to be slow, spanning decades or more. Let's look at some examples (also from Smil's Energy Myths and Realities):

- For millennia, people relied on biomass fuels to meet their energy needs. Coal did not overtake biomass as the primary fuel source until the late 1880s.

- Oil was first commercially produced in the 1860s; however, it did not reach 10% of the market share until 50 years later. It took another 30 years to raise that from 10% to 25%.

- Natural gas, first available in 1900, did not reach 20% of the total energy market until 1970. Its share in 2008 was just half of what had been anticipated in the 1970s.

What's happening with these energy transitions that are causing them to take so long to develop? Infrastructure is a big consideration. Think about the global infrastructure that exists to extract, process, transport, and utilize our current mix of fossil fuels. Even if we assume a utopian scenario of the discovery of a new energy resource that is plentiful, clean, easily accessible, and cheap, that doesn't change the reality of our past investments. And the physical infrastructure is only part of the equation. There's also a global workforce of individuals whose livelihoods are based on the development of these resources.

In addition, people are creatures of habit, and a reluctance to accept change can be a significant challenge to overcome in the quest to grow the market share of a new energy resource. One easy example is that of hybrid cars - many people are uneasy about purchasing an alternative fuel vehicle because they fear the unknown. What if something happens to the battery? The technology is still too new. Our own reluctance to accept new risks influences the marketplace. Many people are willing to accept less efficiency for more predictability.

A New Transition is Afoot

And now we find ourselves in the midst of the next big energy transition as we look to move beyond the hydrocarbons that have propelled our society for two centuries now in favor of lower-carbon, more environmentally sustainable alternatives. The transition to a low carbon economy is one borne more out of necessity from the perspective of addressing climate change than it is a response to dwindling supplies of fossil-fuel-based energy supply. However, that concern also factors into the decision. And like the energy transitions of the past, this one is playing out over an extended time frame, though the more rapid deployment of technology over time (generally speaking) may expedite this journey a bit. And while we can't perfectly predict how the transition will unfold, corporations and governments the world over are trying to understand the likely scenarios and plan for them.

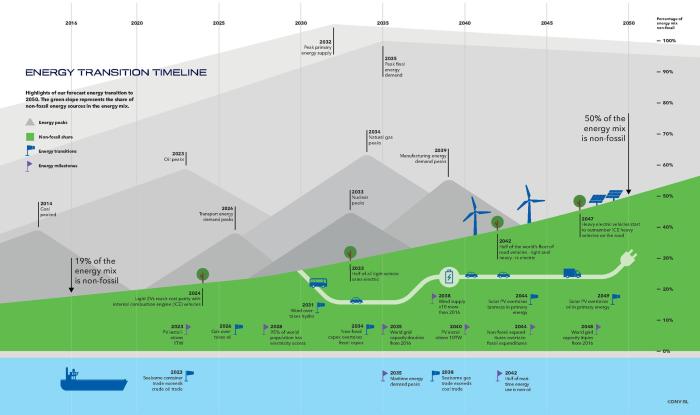

This graphic below is really nicely done because it lays out peaks in various resource use as well as the overall peak in our global demand for energy along with the ramping up of renewable capabilities. DNV GL offers a projection of the next 10 years here (spoiler: there is progress, but we are not transitioning fast enough to carbon neutrality), if you are so inclined. This is of course one think tank's best guess at what the transition will look like as they seek to prepare their partners for the changes ahead. Can you find examples of other models of what our transition to a sustainable energy future might look like? Feel free to share them in our HAVE A QUESTION discussion board!

Highlights of our forecast energy transition to 2050. The green slope represents the share of non-fossil energy sources in the energy mix.

ENERGY PEAKS:

- 2014: Coal Peaked

- 2023: Oil Peaks

- 2026: Transport energy demand peaks

- 2032: Peak primary energy supply

- 2033: Nuclear peaks

- 2034: Natural gas peaks

- 2035: Peak final energy demand

- 2039: Manufacturing energy demand peaks

ENERGY TRANSITIONS:

- 2023: Seaborne container trade exceeds crude oil trade

- 2026: Gas over-takes oil

- 2031: Wind overtakes hydro

- 2034: Non-fossil capex overtakes fossil capex

- 2038: Seaborne gas trade exceeds coal trade

- 2044: Solar PV overtakes biomass in primary energy

- 2049: Solar PV overtakes oil in primary energy

ENERGY MILESTONES:

- 2023: PV installations 1TW

- 2028: 95% of the world population has electricity access

- 2035: World grid capacity doubles from 2016

- 2035: Maritime energy demand peaks

- 2038: Wind supply x10 more than 2016

- 2040: PV installations 10TW

- 2042: Half of maritime energy use is non-oil

- 2044: Non-fossil expenditures overtake fossil expenditures

- 2048: World grid capacity triples from 2016

NON-FOSSIL SHARE:

- 2024: Light EVs reach cost parity with internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles.

- 2033: Half of all light vehicle sales electric

- 2042: Half of the world’s fleet of road vehicles - light and heavy - is electric

- 2047: Heavy electric vehicles start to outnumber ICE heavy vehicles on the road

2016: 19% of the energy mix is non-fossil

2050: 50% of the energy mix is non-fossil

The Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution

It would be difficult to discuss the history of human energy use without at least a brief discussion of the Industrial Revolution. And, in a class where we're focusing on energy not just for energy's sake, but also incorporating the climate impacts of our energy use, it's absolutely critical.

And while we tend to think of the Industrial Revolution in a historical context, because it occurred so long ago in the western world (starting in England, and spreading readily to other European countries and the colonies now known as the US), it's important to remember - especially in the context of energy policy - that much of the world is still striving to achieve industrialization. Industrialization serves as a major sticking point for international climate policy negotiations, with lesser industrialized countries lamenting the fact that the western world enjoyed unmitigated development with cheap, dirty fuel sources and had no climate considerations burdening their desire to grow and evolve. The western world, however, recognizes the implications of continued growth in carbon-intensive fuel sources to support a higher quality of life around the world and (from the luxury of their industrialized societies) calls for cleaner, more expensive energy alternatives moving forward.

The Industrial Revolution marks a turning point in how we viewed energy, consumption, and our environment. Prior to this, the manufacturing process was small and on a highly localized scale. Skilled laborers worked in small groups to create complex goods. The Industrial Revolution saw increased farm production and efficiency, allowing more people to abandon subsistence farming for livelihoods in industrial centers. Fewer farmers feeding more people allows society to advance and branch out in all areas, with individuals able to devote time to livelihoods in manufacturing, textiles, services, and other areas.

And while it's termed a 'revolution,' these changes still took time. Remember our discussions about energy transitions and how they are slow-moving events? The Industrial Revolution was no exception to that. The primary difference here is that the Industrial Revolution marks a time in history when we had a fundamental shift in how we did things, and this transcends just a system of factories. Agricultural practices, economic policies, and societal norms were all upended to make way for more efficient ways of doing business and a rapid pursuit of a higher quality of life. On a rudimentary level, we can think about the Industrial Revolution as being similar to the advent of e-mail. E-mail fundamentally changed how businesses operate - and seemingly helped make them more efficient. Good news - we didn't have to unlock millions of years' worth of carbon for the e-mail revolution.

Joking aside, you can probably pinpoint a few major shifts in how we operate. But even as revolutionary as some of our recent technological advancements have been, few things will ever be quite the spot-on history that the Industrial Revolution has been. Lumped under this heading is a series of events that cascaded into the very real quality of life improvements for people of the times, and people today. Modern-day conveniences like washing machines and sewing machines (just to name a few) owe their roots to the Industrial Revolution.

But, for many people living the reality of the changes on the ground, it wasn't all good. Poor working conditions, child labor, crowded living conditions with little sanitation, and extreme air pollution are but a few of the consequences of the growth and advancement during this time. And lest we forget that industrialization in the West would not have been possible without the horrors of slavery and colonialism (and the illiberal practice of neocolonialism that arguably exists today), as well resource exploitation. And this phenomenon is not only historical. A bevy of research has found that airborne pollution - largely from manufactururing and energy generation associated with industrialization - causes major health impacts. One recent study found that pollution reduces the averages Chinese citizens' life by almost 3 years. There are negative impacts from things like mining rare earth metals, toxic electronic waste pollution, land grabs to secure raw materials, and more - all resulting as a consequence of the current energy transition and global industrialization. These impacts are disproportionately visited upon marginalized populations domestically and globally. It's important to keep these side effects in mind as we think about radical shifts in energy sources. While our goal to be more efficient and provide more people with a better quality of life isn't all that different from the goals of large-scale industrialization, we must be mindful of the unintended consequences and externalities of our actions.

'Soft' and 'Hard' Energy Paths

In 1976, Amory Lovins wrote about 'hard' and 'soft' energy paths (which you'll be reading all about in this week's assigned reading) and how the path the nation chooses would dictate the energy future that would follow. Now, more than three decades later, we can recall the energy futures Lovins predicted based on policy choices in the 1970s and understand the implications of energy policy of that time.

Characteristics of hard energy paths:

- centralized high technologies

- increasing supplies of energy (especially electricity)

The Negawatt Revolution 1989

Characteristics of soft energy paths:

- emphasis on energy efficiency

- development of renewable energy sources - matching in scale and quality to the end use need

The Negawatt Revolution 1989

Energy in Transition Summary

Summary

In this lesson, we've taken a brief look at human energy use throughout history. By understanding how people have harnessed energy resources in the past, we can more fully appreciate the nuances of our energy challenges moving forward. We've learned that energy transitions of any kind take time, money, and support in order to be successful - and often take more of each of these things than initially estimated or anticipated. Understanding these patterns of transition has critical importance for effective and realistic energy policy development. Establishing achievable timetables for measured success requires an understanding and appreciation of the pace with which new energy resources can realistically be expected to have any real impact commercially.

One fact that will be critical for us to remember as we continue on in the course is that we're always writing history - so be thinking about what students taking a graduate-level energy policy course will be learning about in 30 years. Or 50. What will be the history we write? Will it be one of the rapid adoption of more sustainable and renewable energy technologies with more distributed infrastructure? Will it be one of the continued reliance on traditional fossil fuels with little widespread adoption of newer sources? These are tricky questions to answer, given the likelihood of currently unpredictable events that will shape our energy outlook and policy. Unforeseen technological advancement, new scientific discovery highlighting major benefits or detriments of any particular energy resource, and the real wild card of societal behaviors and preferences make it difficult to foresee what's coming. Thirty years ago, it would have been nothing short of science fiction to imagine an iPhone, or how my new car (a hybrid) coaches me as I drive to drive it with maximum efficiency - spitting out nearly continuous MPG data and suggestions for improvement. Only fifteen or so years ago, the thought that electricity from renewable energy would be as cost-effective as coal or natural gas (aka grid parity) was almost laughable. Now properly-stied onshore wind and utility-scale solar are cheaper on a levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) basis - without subsidies.

This course is designed to approach issues of energy policy in a two-pronged (somewhat conflicting) manner.

- Dream Big. I want you to think outside the box, imagine radical shifts in thinking and governance, and develop idealistic and utopian views of our future. What future do you want to see, and how can we get there?

- Stay Grounded. I also want you to recognize all of the constraints and conflicts tugging at the very core of energy policy - current and future. Our social, cultural, economic, and political circumstances are real and likely here to stay.

It's my hope that if we take a little bit of each of these approaches, we can all learn something about the energy policies governing our world and what exactly we need to do to improve them. Without the ability to dream big, we get stuck in the status quo, and our policies don't change and evolve with the times. But, if we don't stay grounded to some extent, we risk losing the ability to affect real change in the social constructs in which we must operate. Finding this delicate balance will be our goal.

This lesson was also about tradeoffs.

- There is no magic energy source. As we continue to refine existing technologies and develop new ones, we may be improving upon the social and environmental consequences of our energy consumption, but we cannot yet eliminate that from the equation. We value non-renewable energy resources for their abundance and relatively cheap costs ("cheap" ignoring externalities, of course), but are becoming increasingly discontented with their environmental pollution and social impacts, particularly with regard to greenhouse gas emissions. We value the lower emission rates of renewable resources, but find the costs, lack of social acceptance, and new environmental consequences to be barriers to widespread adoption. With this foundation, let's take a look at how policies can help alleviate some of these challenges to renewable resource adoption!

- The path we've chosen might be a bumpy road. In your review of the Amory Lovins article, you learned that even several decades ago, people were questioning our energy choices and the consequences we'd be faced with depending on what we value most in energy in this country. While his concepts of hard and soft energy paths might seem a little extreme on either end of the spectrum, he illustrates the point that we cannot (yet) have it all. Cheap, centralized energy is dirty. Energy efficiency and conservation are hard to incentivize with cheap energy. If nothing else, walk away from that article with the understanding that the decision to hop from one path to another is a complicated and daunting proposition, and one which requires strong policy decisions.

Reminder - Complete all of the Lesson tasks!

You have reached the end of this lesson! Double-check the Lesson Requirements in Canvas to make sure you have completed all of the tasks listed there.

2: Climate Policy is the New Energy Policy

About This Lesson

This lesson is structured to make you think about the interconnected nature of energy policy and climate policy.

During the Trump Administration, the United States lost virtually all momentum behind meaningful national climate policy. Efforts to meet targets associated with the Paris Agreement were halted with our intent and then formal withdrawal from the compact. The Clean Power Plan was replaced with the Affordable Clean Energy Rule. These are just a few of the larger examples of efforts to undo work set in motion by the Obama Administration to help us meet our Paris Agreement targets. However, with the start of the Biden Administration, the US rejoined the Paris Agreement, and the IIJA and the IRA both have hefty climate-friendly provisions which we'll explore in more detail later this semester, but for now I still want to take a minute to talk about the Clean Power Plan.

When considering the relative merits and challenges of addressing climate at the local scale, one issue that often comes up a lot as a benefit of local action is the ability to tailor the plans to the specific geographic, economic, and other circumstances of a location. But one of the challenges with thiis is that effectiveness may partially depend on support from higher levels of government. To some (myself included), the Clean Power Plan was the best of both worlds - it was national in scope, but allowed states the flexibility to craft their own paths forward to meet its targets. And while it's not active right now, I think we can use this as a model for how we can think about crafting large scale climate policy that is both effective (reaching large swaths of emissions generating activities) and flexible. So even though that Plan is no longer in place, I raise it here because it exemplifies a flexible policy mechanism that I think is critically important for addressing a problem such as climate - covering the totality of the country, but with state-specific flexibility and consideration for nuances in local and regional participation in our energy economy.

Here is a short clip put out by the Obama White House explaining the Clean Power Plan. However, if you're like me and want more detail, I recommend checking out the Press Conference (just under 30 minutes) from when President Obama announced the plan. While it might not seem immediately relevant given it's currently defunct, it still represents a fundamental shift in the way climate policy is crafted, creating a national umbrella with flexibility for states to meet requirements tailored to their own economic and environmental realities. In time, we may see something like this reemerge.

President Obama on America's Clean Power Plan (2:26)

The President: Our climate is changing. It's changing in ways that threaten our economy, our security, and our health. This isn't opinion; it's fact, backed up by decades of carefully collected data and overwhelming scientific consensus. And it has serious implications for the way that we live now. We can see it and we can feel it: hotter summers; rising sea levels; extreme weather events like stronger storms, deeper droughts, and longer wildfire seasons. All disasters that are becoming more frequent, more expensive, and more dangerous. Our own families experience it too. Over the past three decades, asthma rates have more than doubled. And as temperatures keep warming, and smog gets worse, those Americans will be at even greater risk of landing in the hospital.

Climate change is not a problem for another generation. Not anymore. That's why, on Monday, my administration will release the final version of America's Clean Power Plan: the biggest, most important step we've ever taken to combat climate change. Power plants are the single biggest source of the harmful carbon pollution that contributes to climate change. But until now there have been no federal limits to the amount of that pollution those plants can dump into the air. Think about that. We limit the amount of toxic chemicals, like mercury and sulfur and arsenic, in our air and water, and we're better off for it. But existing power plants can still dump unlimited amounts of harmful carbon pollution into the air we breathe.

For the sake of our kids, for the health and safety of all Americans, that's about to change. We've been working with states and power companies to make sure they've got the flexibility they need to cut this pollution, all the while lowering energy bills, ensuring reliable service, and paving the way for new job-creating innovations that help America lead the world forward. If you believe, like I do, that we can't condemn our kids and grandkids to a planet that's beyond fixing, then I'm asking you to share this message with your friends and family. Push your own communities to adopt smarter, more sustainable practices. Remind everyone who represents you that protecting the world we leave to our children is a prerequisite for your vote. Join us. We can do this. It's time for America and the world to act on climate change.

By the end of this Lesson, you will have a greater understanding of:

- the inherent link and overlaps between energy policy and climate policy;

- what climate policy looks like and the issues it specifically addresses;

- US efforts (both nationally and at smaller scales) to address climate change, focusing both on the issues and the highly politicized volatility of the issue;

- the importance (and complexity) associated with global cooperation to solve the climate crisis.

What is due this week?

This lesson will take us one week to complete. Please refer to the Calendar in Canvas for specific assignments, time frames and due dates.

Questions?

If you have questions, please feel free to post them to the "Have a question about the lesson?" discussion forum in Canvas. While you are there, feel free to post your own responses if you, too, are able to help a classmate.

Understanding the link

Energy Policy and Climate Policy

These two are inextricably linked as we move forward. We cannot address the challenges associated with reducing human-induced climate change without taking a good, long look at our energy policies and the resources on which we depend so heavily. So much of the anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions are tied directly to energy extraction, production, and consumption - as you can see in the image below, nearly 75% - therefore, any efforts to reduce these emissions will necessarily have very real consequences for all facets of the energy industry.

In effect, climate policy IS energy policy.

What are the goals of climate policy? While many countries (and other levels of government) are still trying to figure out what an effective climate policy really means for them, we can broadly explore some of the goals of instituting climate policies, recognizing that no one policy can be all things to all people.

Generally, we can sort climate policy objectives into the following two categories:

Mitigation

- reduce anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions understood to be responsible for human-induced warming of our climate

- establish achievable yet rigorous emission reduction schedules

- transition our fossil-fuel intensive industries to lower carbon alternatives in a timely and cost-effective manner

Adaptation

- react to the consequences of current and unavoidable changes

- provide funding and other support to those people disproportionately affected by the consequences of a changing climate

Addressing climate change has always been a two-fold challenge and will continue to be one. In order to avoid more severe consequences of change in the future, we must look for ways to mitigate our emissions now and moving forward. But mitigation efforts alone are not enough, because the emissions we've already released will inevitably impact the climate and because we are already seeing climate change impacts that we must react to. Adaptation policy is often more complex and less easily quantifiable than mitigation policy, but it's important to understand that together they represent a comprehensive approach to addressing global climate change.

US Efforts to Enact Federal Climate Policy

Over the past several decades, there have been various legislative attempts to combat climate change at the federal level, with varying degrees of success. Here is an excellent summary (required reading!) from the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions. You'll see on that summary that several attempts at carbon pricing (mostly through cap and trade) emerged with bipartisan support.

The list stops short of the Clean Power Plan (also 2015), which in many ways was a turning point in US federal climate policy as the first ever energy policy designed specifically to reduce carbon emissions and was done so to position the US for the then-upcoming Paris climate negotiation talks. While we could devote an entire semester (or doctoral dissertation! or career!) to an analysis and discussion of the merits, drawbacks, and politics of climate legislation in the United States, we need to condense it into part of just one lesson in our course. If you find yourself really interested in this material and would like to know more, feel free to explore the links on your own and/or post to the class discussion board.

The Paris Agreement reached in December 2015 built upon the existing momentum that finally, the US is taking climate change more seriously. But what took so long?

Read "Federal Government Activity on Climate Change" from Ballotpedia (you can start at "Policy History (1992 - 2009). This is a few years old now, but provides a valuable perspective on the then-current state of affairs related to attempts to institute federal action on climate change, including bonus coverage of Massachusetts v. EPA, a landmark Supreme Court ruling in 2007 that gave the EPA the power to regulate carbon dioxide. And remember, to understand the future of climate policy, we need to know how we got to where we are now.

The Economy....from late 2007 through mid 2009, the United States experienced an economic downturn and recession unparalleled in scope and severity since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Triggered largely by risky lending and the securitization of mortgages, coupled by increases in commodity prices like food and oil, thes "Great Recession" and substantial job loss made it quite a difficult proposition for elected officials to support climate policies perceived (to some extent, correctly so) to increase energy prices.

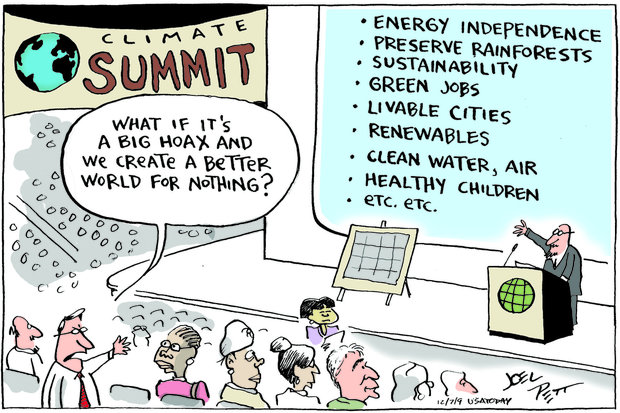

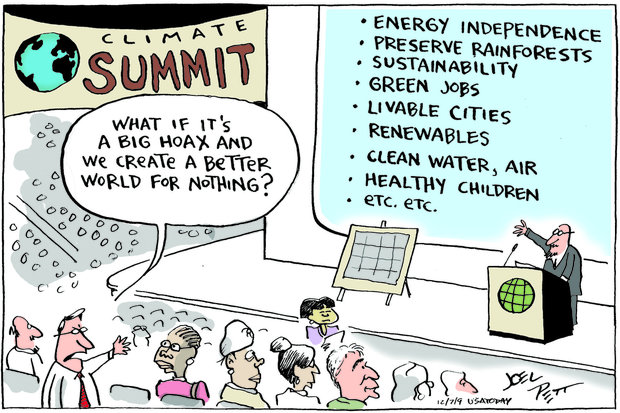

The Politics...every facet of tackling climate change is politically charged. As we saw last lesson, many people question the validity of the science that anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions are influencing our climate system. Others worry that climate policy will affect end users of energy more than energy producers. Still others are concerned that until the fast-growing, developing countries of China and India commit to reducing their unchecked emissions, the United States will put itself at a global competitive disadvantage for manufacturing goods (conveniently ignoring that the U.S. emitted GHGs unchecked for hundreds of years to establish itself as a global superpower). Climate policy is an issue with so much at stake - for everyone - that tensions run high and fears are plentiful. It isn't the goal of this class to draw political lines in the sand - instead, you need to understand the motivations of all sides and how the vested interest of various parties influences the decisions that are made about this issue.

This is a list (certainly not exhaustive) of some of the major attempts at climate legislation in the House and Senate over the past several years. While somewhat redundant with the C2ES list linked above, I include it here mostly for the summaries of these various pieces of legislation. I encourage you, as you're working on your research projects, to seek out summaries from credible, non-partisan think tanks. They can be quite helpful!

The Process...In case you are not familiar with how a bill becomes law, here is a good summary from USA.gov, and here is a more detailed explanation - including videos that provide a step-by-step explanation of the process - from the U.S. Congress.

Of course, the process is almost never this straightforward, as things such as "horse trading" (I'll support your bill if you support mine, I'll support your bill if you publicly state this or that, etc.) and political posturing have resulted in this process often being referred to as "sausage making" after the famous quote: "Laws are like sausages, it is better not to see them being made." Whether Otto von Bismarck said it or not, the quote and characterization are still used to this day.

| Components |

|---|

|

Clean Energy Jobs and American Power Act (2010)

|

|

Lugar Practical Energy and Climate Plan (S.3464) (2010)

|

|

Clean Energy Jobs and American Power Act (S.1733) (2009)

Pew Center Summary of the Clean Energy Jobs and American Power Act |

|

American Climate and Energy Security Act of 2009 (ACES)

|

|

The American Clean Energy Leadership Act of 2009 (S.1462)

Pew Center Summary of American Clean Energy Leadership Act of 2009 |

|

|

Climate Equity Act of 2020 (H.R. 8019)

|

|

H.Res.319 - Recognizing the duty of the Federal Government to create a Green New Deal

|

In the Absence of Federal Legislation - Climate Policy at Smaller Scales

As we've discussed earlier, climate policy is energy policy - and often actions we can implement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions are cost-saving and carry additional ancillary benefits. It's no surprise, then, that in the absence of a federal climate policy, smaller scale bodies of government are working hard to address these challenges in their own regions, states, and localities.

We find ourselves at a tumultuous point in US climate policy history. Retreating from the commitments of the Clean Power Plan and the Paris Agreements and renewed investment in the fossil fuel industry puts us at odds with what the scientific community understands about climate change and the actions we must take to address it. As you can imagine, in the years (decades, really) prior to 2015, the very noticeable absence of federal leadership on this problem created a void smaller geographic scales just couldn't ignore. The next several pages of this lesson will take you through the climate policy efforts which emerged at a variety of sub-national geographic scales and introduce you to new ones growing out of the stalled progress we've seen in the past several years with federal climate policy until the Biden Administration took over. Now, these efforts are to a large extent supported by federal initiatives, and so it will be interesting to see what kind of progress can be made while the IRA and IIJA rubber starts hitting the road. As the Rhodium Group notes, the IRA should "provide a decade of policy certainty" supporting emissions reductions and a change in the energy industry, which has never happened before.

As you read through these pages, think about the advantages and disadvantages to tackling these problems at different geographic scales (geography matters!). Greenhouse gas emissions are a unique environmental problem, in that, while emissions are localized and certainly the impacts of climate change are localized, the problem is global. Think about this - most GHG emissions come from the industrialized and rapidly developing parts of the world, the US, China, India. But that doesn't mean these are the countries most adversely affected by a changing climate (take a look at which places are most vulnerable). Rather, some of the most disproportionately affected countries are unindustrialized, low-lying island nations and coastal regions. So, emissions reductions in a given area don't always correlate to reducing that same location's vulnerability to climate change. Quite frankly, our comfortable western lifestyles run up a carbon tab that folks in Bangladesh or Vanuatu (or any other number of places) must pay.

Addressing climate and energy challenges at smaller scales of government offer a degree of flexibility in the strategies implemented to solve the problems which are best suited to a particular place in a way that a blanket federal approach would fail to accommodate. It affords policy makers the opportunity to explicitly tailor plans to the economic, social, and environmental factors and incorporate these place-based nuances into their decision-making process. However, the piece by piece approach also leaves room for inconsistency, and for leakage of emissions from more stringently regulated states to those which are more lax, and may fail to spur innovation across all states. This was really what was so innovative (and smart) about the Clean Power Plan's design; it was structured to strategically have the best of both worlds - a federal program with national targets which allows states to choose their own pathways to meeting reduction goals.

As you go through the various sub-national scales of climate action, think about where you live and what action, if any, your region, state, or municipality has taken. Do you live in an active region? Or, is there a lot of work to do? Maybe that's work you will want to do when you graduate!

Regional Initiatives

Without national climate policy, regional efforts sprout up

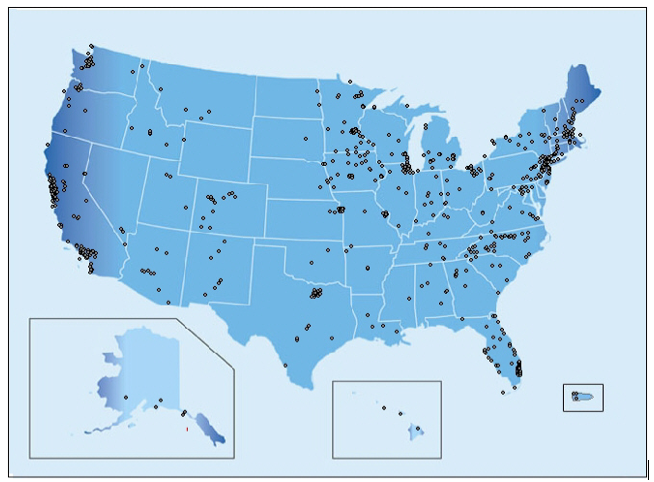

Despite the federal government's ability to enact comprehensive climate legislation to mandate a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (the IRA should lead to emissions reductions, but to not mandate it), much of the United States is moving forward to address climate change.

There are 3 Regional Programs committed to greenhouse gas reduction which together represent 23 states and 4 Canadian provinces, and account for half the US population and more than a third of US greenhouse gas emissions.

These programs represent a widespread interest in mandatory greenhouse gas reduction across the country. As you look at the participating states and provinces, you'll see a wide diversity of politics, resource consumption, economies, and environmental concerns. Their willingness to address climate issues represents not only an acknowledgment of the problem, but also an acceptance of the challenge of solving the problems while juggling economic and political considerations. Because the states are all so varied, addressing climate change at this sub-national scale represents an opportunity for the states to tailor their programs specifically to their assets and handicaps.

| Program | Participant(s) |

|---|---|

| Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative and TCI | Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Maryland, Delaware, Pennsylvania (new as of 2022 via Executive Order by Governor Wolf) |

| Midwest GHG Reduction Accord | Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas |

| MGGRA Observer | Ohio, Indiana, South Dakota |

| Western Climate Initiative | Washington, Montana, Oregon, California, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico |

| Western Climate Initiative Observer | Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, Nevada, Alaska |

1. Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI)

RGGI was the first (and currently the only) mandatory cap and trade system for the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions in the United States. It covers power plant emissions in 12 Northeastern/Mid-Atlantic states. It originally called for a 10% reduction in those emissions by 2018 and now have a goal of 30% below 2020 levels by 2030 in covered power sector emissions (any 25 MW or greater poewr plant).

Emission allowances are auctioned off, and the proceeds are re-invested in energy efficiency, clean energy technologies, and other related programs.

We can look at the RGGI program as a pilot program for national cap and trade - either economy-wide or just of the utility sector.

2. The Midwestern Greenhouse Gas Reduction Accord (MGGRA)

The Accord is comprised of 6 states and 1 Canadian province (and 3 observer states and 1 observer Canadian province). Members are charged to formally commit to greenhouse gas emission reductions, set regional targets for reductions, and establish a multi-sector cap and trade system to reach their goals.

3. The Western Climate Initiative (WCI)

There are 7 states and 4 Canadian provinces participating in the WCI along with 4 Canadian provinces, 6 US states, and 6 Mexican states signed on as observers. The WCI has committed to reducing their regional greenhouse gas emissions to 15% below 2005 levels by the year 2020 and will do so by implementing a market-based cap and trade system, similar to the future plans of the Accord and the existing RGGI program. The notable difference between WCI and RGGI is that WCI is a non-profit that provides technical assistance. Each state designs its own program. Whereas RGGI is a coalition of states that trades with each other and is managed by RGGI.

State Initiatives

Many states across the country have drafted, adopted, and implemented climate action plans. Some states have done this as part of their commitment to regional initiatives. In addition to making the progress we need now to address the climate crisis, these state level efforts might just spur federal action, too.

How does state climate action take shape? In many cases, state-level policy makers and stakeholders enlist the assistance of external groups to help them determine an appropriate list of actions and policies the state could adopt, to achieve climate goals. Often this process begins with an inventory of the state's greenhouse gas emissions across sectors, and then the adoption of reduction targets. It's quite similar to how actions arise at larger scales. Groups such as the Center for Climate Strategies come in and meet with relevant state stakeholders to scope inventories and devise strategies for emissions reduction and cost savings.

When the Trump Administration came into power and started the procedure to eventually withdraw the US from the Paris Climate Agreement and dismantled the Clean Power Plan, states took notice. Many had already been preparing for the coming Clean Power Plan requirements, and therefore weren't going to suddenly backtrack on those investments simply because the federal political winds had changed. States are often better at seeing the ancillary economic and environmental benefits, are moving forward as if the plan were still in place. In Pennsylvania, Governor Wolf signed an executive order in January 2019 to address climate change and conserve energy, and eventually signed an Executive Order joining RGGI in 2022.

What is your state doing? There are several websites providing information about state-level climate planning across the country. Find out if your state has a climate action plan!

- Center for Climate and Energy Solutions - This website allows you to click on states for their climate action plan status an provides links to the document.

- EPA Climate and Energy Resources for State, Local, and Tribal Governments - This archive of the EPA website offers information on state and local initiatives and resources. Though not part of the current EPA site, a wonderful resource!

Local Initiatives

Local Governments Solving A Global Problem

While we tend to think of climate change as a global problem, the solutions are often highly localized in nature. Therefore, it makes sense that local governments take action to reduce emissions and develop sustainable energy solutions. To an even larger extent than state governments, local scale climate change mitigation efforts offer supreme flexibility for creating solutions tailored specifically to local circumstance. Whether it's an old coal mining town in the northeast hoping to revitalize its economy with newer energy technologies or a farm town in the Midwest seeking additional revenue sources for its small-scale agricultural producers, local action empowers people because they are able to feel more connected to what is happening.

And the story of local action has never been more important than it is right now. Early local action efforts rose out of dissatisfaction with the US decision not to actively participate in the Kyoto Protocol almost 20 years ago now. Local municipalities and states filled the void left by a lack of federal leadership on climate change. During the Obama presidency, that void filled in a bit with hallmark achievements, including the Clean Power Plan and the ratification of the Paris Agreement. Then U.S. again found itself lacking federal leadership on climate action during the Trump Administration and states, municipalities, and private businesses all recognizing that there's simply no time to waste are stepping up to fill the void again. And of course, federal support is a reality again with the Biden Administration. This umnfortunate game of political football has on the one hand stunted aggressive national policies but on the other hand has motivated states and localities to take their own inititiatives.

- Notably, the We Are Still In campaign is a pledge of American businesses, non-profits, universities, and municipalities who remained committed to achieving the reductions outlined in the Paris Agreement no matter what is happening at the federal level.

- The Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy is a worldwide alliance of more than 7,500 cities and towns committed to climate action and provides resources for both inventorying emissions and enacting climate action plans to reduce them.

- The US EPA's Local Climate and Energy Program helps local governments around the country reduce emissions and meet other sustainability goals through training and competitive grants. Check out their website to learn more about what's going on where you live (perhaps you'd like to discuss this with your classmates).

- The International Council for Local Environment Initiatives (ICLEI) has been around since 1990. Their climate program is but one of many sustainability-driven initiatives the Council runs. Their Climate Program is structured into 3 areas - Mitigation, Adaptation, and Advocacy - recognizing that all parts are necessary if we're to address the totality of the problem. Specifically, their Cities for Climate Protection campaign has gained notoriety for drawing more than 1,000 members from local governments all over the world. ICLEI members can draw on an extensive network of in-house research, training programs, and the support of other members as they devise strategies for handling climate policy at their local government level. Signatories to the Global Covenant are able to access ICLEI's ClearPath software for free to conduct local GHG inventories.

- The Urban Sustainability Directors' Network joins together folks working on sustainability issues in towns and cities across the country. This focused group allows them to share ideas and best practices about programs and approaches which work.

What about your community? What's going on there? If not, maybe it's time for you to change that! You could start by revieweing some of the resources above, which provide a wealth of suggestions and models, as well as best practices. It only takes one person to get something going, especially at the local level!

Climate Policy without (in spite of?) Congress

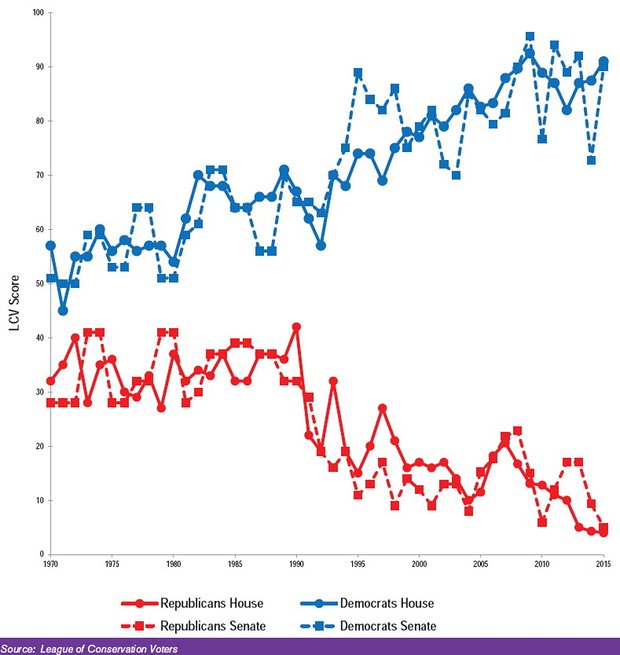

While climate change has not historically been a politically divisive issue until recent years, the fiercely partisan divide as it currently exists makes garnering the support necessary for meaningful change very challenging.

Despite Congressional stalemates to produce meaningful, broadly-scoped legislation to address greenhouse gas emissions, President Obama utilized executive authority to regulate emissions under the Clean Air Act based on the landmark 2007 Supreme Court ruling that categorizes carbon dioxide as a threat to human health. In doing so, he directed the EPA to establish rules for both new coal-fired power plants, and perhaps more controversially, for existing coal-fired power plants (in what became known as the Clean Power Plan). The former was viewed by environmentalists as a bit of a lame duck policy, since you could argue that in 2014, it seems silly to be building ANY new coal-fired power plants. But to regulate the 600+ existing facilities in the country - this could have wide-reaching implications for not only emissions themselves, but also how we as a nation view and value the carbon cost of our energy generation.

The Trump Administration rolled back the Clean Power Plan and implemented the Affordable Clean Energy Plan, which significantly neutered the original legislation. This afforded states more authority to choose to regulate (or not regulate) the emissions from their power plants, citing executive overreach of the Clean Power Plan's structure. As we know, the main federal climate policy since then is the Inflation Reduction Act, though the Infrastructure Investment Act also addresses emissions.

But what did the rollback really mean for overall emissions reductions?

It depends on where you are.

This NY Times summary provides an excellent overview (and these great maps!) of what the rollback (and eventual repeal) would really mean. Remember, a lot of actions were already set into motion before the Trump Administration rolled back the requirements. So for some states, moving forward regardless of the current political winds just makes good economic sense based on recent investments.

You can learn more about the Greenhouse Gas Tailoring Rule that lays out the specifics for regulation under the Clean Air Act, as well as a brief history timeline of this action. EPA went on to structure the proposed rules to afford states the flexibility to meet their emission standards through the employment of a cap and trade system or carbon tax. And while these efforts would have certainly been smaller in reach than an economy-wide system, because these stationary sources are such a big part of the emissions profile, the potential GHG reductions are profound.

The Center for Climate and Energy Solutions offers this list (required) of ways in which Congress can work to achieve GHG emissions reductions without necessarily explicitly crafting climate policy.

This C-SPAN video is from the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee hearing at the time of the Supreme Court Endangerment finding in 2007. That finding opened the door for EPA to regulate carbon dioxide under the Clean Air Act, resulting in the Clean Power Plan proposed rules mentioned above. It's two hours long and quite old now, but it might be something you're interested to have playing in the background while you work on something else - this is footage of our lawmakers in action. Senator James Inhofe (R-Oklahoma), might be one of the most vocal climate change deniers in the entire Congress, so that keeps things interesting. And if you remember, he then chaired this committee in the Senate.

Global Cooperation

In this lesson, we've learned about climate and energy policy at all scales of government, from local municipalities to intergovernmental panels. Climate change is unlike many other environmental challenges, in that it is a global issue. So, while we can all work separately to achieve reductions in greenhouse gases locally, we can't fully address the problem without global cooperation.

Global cooperation on anything is a challenge in itself. Integrating the disparate interests, intentions, and abilities of all the world's nations and finding a path forward is daunting to even consider. As the Kyoto Protocol experience illustrated, we really need to all be in this together. Will climate change be the ultimate tragedy of the commons? Will some countries recognize the economic potential of developing large-scale renewable energy technologies and out-compete us on the global stage? Will the US rise to the challenge of addressing climate change while managing a weak economy and public misunderstanding of the issue? These are not questions we can answer easily in one lesson or one course. But these will be the types of questions you may find yourself working on as an ESP graduate or any field that deals with climate/energy policy.

Yearly Meetings of the IPCC

Each year since 1995 the UNFCCC's Conference of the Parties (COP) gathers to discuss a global response to climate change - both in terms of mitigating future climate change through emissions reductions and adapting to the change we're already committed to experiencing thanks to present and past emissions. (COP 1 was in Berlin, Germany in 1995.) For many years, it seemed that the venue was the only thing that really changed at the annual climate talks. Until Paris.

Paris 2015: The year we finally did something.

At the COP 21 in Paris in late 2015, participating countries signed a landmark agreement to contain global average temperature warming to less than 2 degrees Celsius (with an ultimate goal of keeping it much closer to 1.5 degrees). Unlike the framework used to develop the Kyoto commitments 20 years ago, one of the most important developments which led to the success of getting 195 countries in agreement in Paris was to focus less on this developed vs. developing country designation for responsibility for reducing emissions. Instead, many of the largest emitting developing countries (like China and India) have come together to acknowledge the role they, too, must play in reducing global emissions. The agreement acknowledges that developed countries must take the lead in reducing emissions, but it does not absolve developing countries of setting and meeting targets. You can read the entirety of the Paris Agreement on the UNFCCC website. And while the Trump Administration withdrew the US from the Agreement, the rest of the world marched boldly on - recognizing the gravity and urgency of the climate crisis we collectively face - until the Biden Administration entered the U.S. back in on his first day in office, 20 January 2021. Until the Biden Admiinstration signed on, the US was the only country to not be party to the Agreement, after the other remaining holdouts - Nicaragua and Syria - had signed on a few years prior.

COP 27 - Sharm-el Sheikh

One of the important outcomes of COP 27 was the establishment of the Loss and Damage Fund, which "allocates money to assist low and middle-income countries respond to climate disasters" according to Reuturs. There was also some movement on limiting or eliminating the use of coal. Reuters provides a good summary here.

COP 26 - Glasgow

Some important agreements were made in Glasgow in 2020. This includes the Glasgow Pact, which - though not containing any binding requirements - recognizes the importance of immediate and sustained action in a number of ways, including providing funding for mitigation and adapation, as well as moving away from fossil fuels. See a summary of agreements and deficiencies here, from the UN.

COP 25 - Madrid

COP 26 in Madrid, Spain was a mixed bag of successes and failures to reach agreement. See a summary from Carbon Brief here.

COP 24 - The Kawotice Rulebook

Learn more about the outcomes of the COP meeting in December 2018. Despite the US plans to withdrawal formally from the Paris Agreement, the rest of the world remains committed to achieving the Paris Agreement goals.

Past COP Meetings Leading to the 2015 Paris Agreement

Lima 2014

Lima set the stage for the success of the Paris talks. The Lima Call for Climate Action laid the foundation for the idea that the agreements reached in Paris would be binding for both developed and developing countries. Nothing agreed upon in Lima really had any strong enforcement behind it, it was merely a stepping stone for what was expected to come in Paris the following year.

Warsaw 2013

Participants have agreed to stay on track to adopt a new 'universal climate agreement' in 2015 which will be implemented no later than 2020. In preparation for this, countries have been instructed to begin working on logistics at home in advance of the next COP in Peru so that everything will be set by 2015 in Paris. Another big outcome of this meeting was the decision to increase funding for vulnerable countries experiencing damages and hardships from severe weather events and rising sea levels.

Doha 2012

Like many of the meetings before it, a primary point of debate for this series of talks is the developing and developed country classifications for the purpose of emission reduction and adaption funding responsibility. Near the end of the meeting, participating countries did finally adopt the agenda of the Durban Platform.

Durban 2011

The most significant development to come out of this Conference of Parties was the Durban Platform. For the first time in global climate negotiations, this document sets for binding targets for all parties. This is a significant deviation from earlier agreements and incremental progress that has focused primarily on the developed/developing country divide.

Cancun 2010

This meeting followed the disappointments of the 2009 Copenhagen meeting as member countries left without making any real, solid progress on post-Kyoto plans for global reductions in emissions. The hopes for Copenhagen had been high - the US had a sitting president (Obama) who expressed interest in the importance of climate legislation, and had the Congressional backing to do so. But, the high hopes of Copenhagen were eventually met with disappointment, as that meeting failed to produce a binding climate deal. (Read about what went wrong at Copenhagen). Therefore, expectations going into the Cancun negotiations were much more measured and conservative. This means that they did not tackle some of the broad, contentious issues that have held up previous meetings, but instead focused on some important, more narrowly defined issues.

Some outcomes of the Cancun Climate Negotiations include:

- stricter and more detailed reporting guidelines for measuring, reporting, and verifying greenhouse gas emission mitigation efforts;

- $30 billion in aid through 2012 (called 'fast-start' funding) and eventually $100 billion in public/private funding annually by 2020 for mitigation efforts;

- developing national strategies to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (known as REDD).

Climate Policy: Summary

In this lesson, we've explored the connection between energy policy and climate policy. Climate change mitigation is a relatively new consideration for energy policy, but the ancillary benefits from enacting policies to curb anthropogenic climate change often overlap with goals of modern energy policy like improved efficiency, decreased dependence on foreign oil, air quality improvement, and job creation. I've tried to introduce the idea of scale of governance as a key factor in climate policy considerations, as it will factor particularly predominantly in this SP 2020 offering of the course with our local scale climate action planning project. We'll get into a bit more detail later this semester, primarily through assigned readings, but this lesson was intended to give you an overview of the interconnected nature of climate and energy and get you thinking about scale. Geography matters!

Important Concepts to take away from this lesson

- Climate policy inherently is energy policy - because so much of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions results from the combustion of fossil fuels to meet our energy needs, any policy to address climate change has substantial consequences for energy policy as well.

- Climate policy is happening at every scale - local climate change efforts enjoy the specificity of really addressing a place's unique circumstances, while national scale policies have the benefit of influencing international agreements on the issue. Regional efforts combine the like-minded goals of geographically clustered states to address climate issues and take advantage of regionally specific resources and talent in the absence of more direction from the federal government. It is the combined efforts at all scales that will allow us to tackle the problem holistically. Our lawmakers may be unwilling to address greenhouse gas emissions at a large scale, but there are other legislative courses of action, namely through the Clean Air Act, that we can pursue. Perhaps they aren't as efficient or practical, but they are likely better than nothing.

Reminder - Complete all tasks!

You have reached the end of the Lesson! Double-check the Lesson Requirements in Canvas to make sure you have completed all of the tasks listed there.

3: The Future is Local

We often think about climate action at the bigger scales - national, international, etc. It's a planetary problem, so we need a planetary solution. However, with cities responsible for 70% of our carbon emissions, the solutions to the climate crisis are inherently local ones. At COP28 in Dubai in December 2023, a recurring theme was local action. Leaders from around the world agreed that without effforts in subnational governments and civil society, the Paris Agreement commitments were not within reach.

About this Lesson

By the end of this Lesson, you should be able to:

- compare the differences between various locales' GHG emissions profiles and identify common energy-based contributors such as transportation, waste disposal, and land use;

- explain aspects of the complexity and variation of user-specific local energy use;

- describe several ways that industrial, residential, and commercial practices contribute to local GHG emissions;

- identify ways that local governments, universities, businesses, and environmental, social, and faith-based organizations are each leading local efforts to mitigate GHG emissions;

What is due this week?

This lesson will take us one week to complete. Please refer to the Calendar in Canvas for specific assignments, time frames and due dates.

Questions?

If you have questions, please feel free to post them to the "Ask a question about the lesson?" discussion forum in Canvas. While you are there, feel free to post your own responses if you, too, are able to help a classmate.

Local GHG Emission Sources

Local GHG emissions vary tremendously from place to place, depending on each area’s biophysical, socioeconomic, and cultural contexts. For example, a college town in central Pennsylvania (hey, I know one of those!) will have a significantly different emissions profile than an agricultural area in southwestern Kansas or an industrial city in northwestern Ohio. Indeed, each place’s GHG emissions profile is unique, but a few important sources appear in most locales. Those sources are energy use, transportation, waste disposal, and land use.

Local energy use is complex and varies with the specific type of user: residential, industrial, or commercial.

Residential:& This graph below shows how we're using energy in our homes here in the United States. More than half of it is to heat and cool our spaces (which means this also represents our biggest opportunities to reduce energy demand through gains in efficiency or moderated use). Understanding our energy consumption at home empowers us to make decisions that lower our utility bills and reduce our demand.

Residential GHG emissions are extremely important in both their quantities and their symbolism. Symbolically, residential emissions are vital because almost every person has a primary residence and has (some) control over his or her energy use and resulting GHG emissions. Large opportunities exist in reducing household energy consumption. Local emissions obviously vary with climate, socioeconomic status, energy systems, and more.

- Think about the things you can do in your home to reduce energy use. (I'll go first - I have made three big changes that I see on my now-lower bills: (1) I don't let my dishwasher dry my dishes, (2) I use a lower heat setting on my dryer, and (3) I set the thermostat higher in the summer and colder in the winter by a few degrees each way. Doing those things, I reduced my monthly energy bill by about 25%!

Our energy use at home is determined by a variety of factors. EIA points them out on their Energy Use In Homes page:

- Location - hey look, geography matters! (spoiler alert - geography always matters!) Your climate will dictate your heating and cooling needs, and we already determined those are the biggest piece of our energy use pie.

- Type of housing - Maybe your apartment is snuggled in among others and stays pretty cozy in the winter without needing to crank the heat too much. Or, maybe you rent a house like I did in grad school where I could see my blinds and curtains move when the wind blew because it was so drafty.

- Devices - we're adding devices to our daily lives all the time. I look around my own home at the things we're plugging in - phones, Switches, tablets, a dehumidifier that runs constantly in the basement, our pandemic era acquired chest freezer. These all require energy.

- Size of household - this is an interesting one because there are some efficiency gains to be made by more people living in one spot than occupying separate individual spaces that need to be heated/cooled separately, but that is then offset by the increased demand on laundry, hot water for showers, running the dishwasher more frequently, etc. And, there's the behavioral component. When my husband is away, I adjust the thermostat to a much more energy-saving temperature.

Do you know what kind of energy sources are used to power your home? Check out this visualization from Carbon Brief illustrating electricity sources across the US.

Industrial uses of energy reflect their GHG emissions. Utilities emit the most GHGs; manufacturing emits the next greatest proportion; mining and related extractive industries emit a smaller yet still significant proportion; and all other industrial activities emit a small quantity of GHGs. Manufacturing involves hundreds of products and processes including such diverse activities as dog food manufacturing, yarn spinning, house slipper manufacturing, ethyl alcohol manufacturing, and lime manufacturing. Local manufacturing can be specific and unique, meaning that local GHG emissions from manufacturing can also be specific and unique. For instance, because Seattle is home of Boeing’s main production facilities, emissions from aircraft manufacturing is unusually dominant in that city.

Millions of commercial enterprises consume energy daily. Keeping the commercial space comfortable for employees and customers through lighting, space heating, and ventilation consumes much of the energy, though these percentages are fluctuating as energy efficiency in various areas improves. For example, a decade ago, lighting was 25% of the total. Commercial food preparation also uses a large amount of energy. While local commercial energy use and GHG emissions are unique, but there is a remarkable uniformity in commercial enterprises across modern society. For local scale inventorying work, commercial energy consumption typically generates a 'low-hanging fruit' opportunity to reduce emissions and save building owners/occupants money by doing so. The data in the table below represent the most recent finlized data published by EIA. A more recent Commercial Energy Survey was conducted in 2018 (see Preliminary Results), but the space heating demand shown below has not yet been released (c'mon, EIA!).

Click Here for a text description.

| Type of Energy Use | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Lighting | 10% |

| Cooking | 7% |

| Water Heating | 7% |

| Space Heating | 25% |

| Ventilation | 10% |

| Space cooling | 9% |

| Refrigeration | 10% |

| Electronics | 3% |

| Computers | 6% |

| Other | 13% |

Institutions, which include such diverse entities as government buildings, prisons, military facilities, and schools, colleges, and universities, are important consumers of energy and emitters of GHGs (and are considered commercial buildings). Each local institution has a unique energy use pattern and GHG emissions profile, but, until recently, construction of most institutional buildings focused on building costs and not on energy efficiency. The net result is that the institutional sector tends to waste energy; large opportunities for energy savings and GHG reductions exist.

Local land use varies dramatically over space and time. Different places use their land for agriculture, commerce, industry, transportation, mining, forestry, or conservation. Some places have mixed land use, whereas other places have only one or two primary land uses. Each land use is associated with a particular GHG emissions pattern. Cropland emits relatively large amounts of nitrous oxide from the surface, while pastureland emits relatively large amounts of methane from cattle and other ruminants; feedlots emit much greater concentrations of methane than pastures. Forests tend to be sinks for carbon dioxide, but clear-cutting releases significant amounts of this GHG. Urbanized and suburbanized areas are hotbeds for GHG emissions: they emit large quantities of GHGs through residential, commercial, institutional, and possibly industrial activities; urban transportation activities similarly emit huge amounts of GHGs; even suburban fertilized lawns emit nitrous oxide. Thus, localities must account for their land-use emissions when addressing climate change.

Local Actors

Many different actors are promoting local mitigation. Four important –– or potentially important –– actors are local government, universities, business, and environmental, social, and faith-based organizations.

Local government and politicians have taken leadership for local mitigation at thousands of locations around the world. Perhaps the best case of local government leadership is the U.S. Conference of Mayors Climate Protection Agreement. More than 1,000 mayors have signed the Agreement, committing to the following three actions (Mayors Climate Protection Center, 2011):

- strive to meet the Kyoto Protocol targets in their own communities, through a variety of context-relevant actions;

- urge their state governments and the Federal government to enact policies and programs to meet the United States GHG emission reduction target suggested by the Kyoto Protocol;

- urge the U.S. Congress to pass bipartisan GHG reduction legislation establishing a national emissions trading system.

Universities have proven to be key agents in local mitigation efforts (Knuth et al., 2007). As large institutions, universities emit significant amounts of GHGs and have the expertise to quantify those emissions. They provide moral leadership by developing their own mitigation plans. University researchers develop new GHG inventory and mitigation techniques. Universities educate students about climate change and GHG emissions, often facilitating community outreach involving students. They also often provide scientific expertise to local governments and other local actors to help these entities develop climate mitigation plans. In the U.S. alone, hundreds of universities are engaged in climate change mitigation.

Numerous non-profit, non-governmental environmental organizations are involved in local mitigation efforts, including the following three notable examples.

- ICLEI Local Governments for Sustainability started with 14 international cities in the mid-1990s. Today, this program provides climate mitigation guidance to hundreds of cities around the world, including a couple of hundred in America. The State College Borough, Ferguson Township, and the Centre Region are all ICLEI members. There are many others throughout the state, too! Many of them have joined in the past three years as part of DEP's Local Climate Action Program. Almost a dozen ESP students have partnered with communities in this program to complete their first greenhouse gas emissions inventories and start writing local climate action plans (check out this Penn State News story from April 2020). (I told you, the future is indeed local!)

- Cool Air-Clean Planet is a U.S.-based organization that partners with companies, campuses, communities, and science centers to help reduce their GHG emissions.

- The Center for Climate Strategies has helped at least 40 state governments, their officials, and their stakeholders build consensus and take action on climate change. Their work extends beyond the US, and they're doing low emissions development planning around the world.

Penn State University Park - a local place taking action on climate

We are! Reducing Emissions!

As we think about the unique opportunities that local scale climate action affords, it's worth exploring the unusual localities that are our university and college campuses. Well-delineated and largely autonomous, university campuses offer a different perspective on emissions accounting and reduction efforts. Beyond that, universities and colleges are home to the front lines of education and research related to climate change, and so it makes sense that their campuses could serve as living laboratories for addressing these important contemporary climate challenges.

Penn State has been tracking its greenhouse gas emissions annually since 2002. Fun fact: some of the initial work on this effort as well as their early mitigation planning was born out of the Department of Geography! As you can see in this graph below, not only is your university tracking its emissions, it has adopted relatively aggressive reduction targets and is working toward meeting them. It takes a lot of different efforts and initiatives, each working together, to pull that emissions trend downward. There is no magic carbon bullet here to save us - we must take aggressive incremental action to achieve our reduction goals. The recent Solar Power Purchase Agreement was the biggest piece of that puzzle in a while, and it will continue to pull that curve down by supplying 25% of the university's electricity needs, but even that is just a portion of the story.

You can learn more about the GHG Emissions Inventories (they track them for all 24 Commonwealth campuses, too!) and other sustainability-related initiatives here at Penn State by visiting Penn State Sustainability.

In April 2020, the University Faculty Senate* passed a climate action resolution calling for the administration to take the following actions:

- develop a university-wide climate action and adaptation plan

- reduce purchased electricity emissions by 100% by 2030

- reduce net GHG emissions by 100% by 2035

- increase investment in initiatives focused on climate science, solutions, and management

- engage peer institutions to raise awareness and reduce impacts of a changing climate

It's important to understand that Faculty Senate resolutions are non-binding. So even though this passed quite handily (I think the vote was something like 114-21), it didn't have any teeth (as in, it didn't then REQUIRE that the university do anything with it). It's more of a visible and tangible expression of the collective will of the faculty. And while they didn't have to do anything with it, I can tell you that (1) the administration knew it was coming and was supportive of it being taken up by the Senate and (2) have since started taking action! The administration has convened a carbon emissions reductions task force that is meeting regularly and working to develop an action plan.

*I am very proud to tell you that I (Brandi) was the author of this climate action resolution! While it was a collective effort with colleagues at the Sustainability Institute, I got to bring it to my Senate colleagues for a vote!

One of the things about Penn State is that because we're so big, it can be really hard to keep track of everything that's going on. The Sustainability Institute website has this nice summary of ongoing initiatives related to climate and sustainability, which may be of interest to you.

What about other colleges and universities?

Penn State is certainly not unique in its pursuit of ambitious environmental initiatives and greenhouse gas reduction efforts. However, Penn State was one of the early pioneers in this space. It's exciting to see the breadth and depth of work happening in this space now in a variety of formats:

- AASHE (Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education)

- PERC (Pennsylvania Environmental Resource Consortium)

- Second Nature's University Climate Change Coalition

- Harvard - fossil fuel-free by 2050 and more recently the Harvard faculty votes to divest from fossil fuels

- Top Universities for Climate Action

- We Are Still In -University Climate Change Coalition

But, that's not to say we couldn't be doing more.

Reading Assignment

Reading Assignment (Penn State login required)*

- Deetjen, T. A., Conger, J. P., Leibowicz, B. D., & Webber, M. E. (2018). Review of climate action plans in 29 major U.S. cities: Comparing current policies to research recommendations. Sustainable Cities and Society, 41, 711-727. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2018.06.023 (link in Canvas)

- Stone, B., Vargo, J., & Habeeb, D. (2012). Managing climate change in cities: Will climate action plans work? Landscape and Urban Planning, 107 (3), 263-271. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.05.014 (link in Canvas)