Writing Assignments

There are two primary types of writing assignments in this course: Assignments associated with your Final Project and weekly writing assignments. The weekly assignments do not start until Week 6. The following provides insight into how to approach them. Please read carefully!

- You should think of these writing assignments as mini research papers. What does that mean? Well first, it means that they should not be written like a blog post or journal entry. They should be written using academic language. Try to avoid the use of personal pronouns (I, we, you, etc.) unless necessary. Proper grammar, spelling, punctuation, and capitalization must be used. I have frankly surprised at the number of errors in past submissions that could have been fixed by proofreading.

- This should go without saying, but make sure you answer the question. In the past, some students have submitted very well-written insightful analyses that don't fully answer the question. Needless to say, you will lose points if you do this. Read the question/prompt carfully!

- The overall purpose of these assignments is for you to reflect on the course content, especially the required Canvas readings. This should be clear from the writing prompts. If you are reflecting on the readings, there are certain to be points in the essay where you refer to the reading(s) and use in-text citations. Make it clear that you have read and thought about the readings. The easiest way to do this is to refer to the relevant portion(s) of the readings and cite the readings.

- You should avoid using qualifiers such as “I believe” or “it is my opinion” in these assignments. If written correctly, your analysis will demonstrate that you analyzed relevant literature to arrive at any assertions you make. Instead of stating that “you believe” something, it should be clear in your analysis that when you make a statement that is an opinion that it is based on valid information. Thus, when you make such a statement, it is either implied or directly stated that it is based on the information you analyzed in the analysis, and you should just state it. For example, if you are asked to identify an issue that is best addressed using cost-benefit analysis (CBA). Instead of saying “It is my opinion that cost-benefit analysis is well-suited for climate change legislation” the details of your analysis should make it obvious why CBA is the best option. If you prefer, you can be more deliberate and state something like “Based on the information above…” or “Due to all of these factors, cost-benefit analysis is the best option” after providing your analysis.

- Finally, please note that the feedback that I provide is meant to help you learn from mistakes and to provide suggestions for more effective writing. When I don’t make a comment, it means that everything looks good, though I will make a note if you make a particularly good point or provide a good insight. If I commented on everything that was good, each assignment would be filled with markings and comments. This is not reasonable for a number of reasons. Thus, most of my comments are critiques, and it often looks on the surface that the submission is worse than it is. Keep that in mind when reading my comments.

Citation and Reference Style Guide

I expect that the text and graphics you submit as part of your assignments are original. I use the plagiarism detection service Turnitin.com to assure the originality of course assignments. You may build upon ideas, words and illustrations produced by others, but you must acknowledge such contributions formally. Unacknowledged contributions are considered to be plagiarized. This guide explains when and how you should acknowledge contributions of others to your own work.

Different disciplines adopt different standards for citations and references. Moreover, almost every professional publication enforces its own variation on the standard styles. The most widely used styles include:

- AMA—Used in medicine, health, and biological sciences

- APA—Used in psychology, education, and other social sciences

- Chicago—Used with all subjects in non-academic publications like books, magazines, and newspapers

- MLA—Used in literature, arts, and humanities

- Turabian—Designed for college students to use with all subjects

To reiterate, it is strongly suggested that you use APA in this course. If you use one of the other standards listed above, you must identify which one you are using each time you use it or I will assume you are using APA and grade accordingly.

My go-to guide for citations is Purdue's Online Writing Lab (OWL). Here is a link to their APA guide, and here is a link to a sample paper. (The sample paper is particularly helpful to use as a model.)

A few key points about citations:

- I cannot stress this enough: You must use in-text citations for any information that you looked up or otherwise got from any source or if the information is not common knowledge. Use your best judgment for the latter. If it does not fall under one of these two categories and it is something you already knew, then you don’t have to cite it. For example, if you write that greenhouse gases cause climate change, you don’t have to cite anything because it is common knowledge. If you state that anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions are the primary cause of the observed warming over the past century, you should cite the IPCC’s 6th Assessment Report since that is not common knowledge. (Here is a helpful Q&A from George Brown College.) If this is particularly egregious, you will receive a zero on part of the rubric, or possibly for the whole assignment. This is something you should already know from other courses and was also addressed in the Academic Integrity Training you went through at the beginning of this course.

- Regarding the previous point, remember that in APA the citation is in parentheses and comes before the punctuation. E.g. “Yada, yada, yada (Kasper, 2023).” Note the period comes after the closed parenthesis. A direct quote must have the page number, e.g. (Kasper, 2023, p. 251). If you use a direct quote and the source does not have pages, you should have the paragraph number, e.g. (Kasper, 2023, para. 10). Here is a helpful guide on formatting from Purdue University.

| Text Citations Example #1: A quotation | List the author(s), date of publication, and page number in parentheses at the end of the sentence with the quotation.

|

Paraphrasing: Most often, you will cite ideas rather than quotations. Your ability to paraphrase and build upon the work of others constitutes more convincing evidence of your professional and intellectual development than your ability to assemble series of quotations. The Student Judicial Services office at the University of Texas has published the following excellent explanation of proper paraphrasing (note the extended quotation is set apart as a "block quote"):

Like a direct quotation, a paraphrase is the use of another's ideas to enhance one's own work. For this reason, a paraphrase, just like a quotation, must be cited. In a paraphrase, however, the author rewrites in his or her own words the ideas taken from the source. Therefore, a paraphrase is not set within quotation marks. So, while the ideas may be borrowed, the borrower's writing must be entirely original; merely changing a few words or rearranging words or sentences is not paraphrasing. Even if properly cited, a paraphrase that is too similar to the writing of the original is plagiarized.

Good writers often signal paraphrases through clauses such as "Werner Sollors, in Beyond Ethnicity, argues that..." Such constructions avoid excessive reliance on quotations, which can clog writing, and demonstrate that the writer has thoroughly digested the source author's argument. A full citation, of course, is still required. When done properly, a paraphrase is usually much more concise than the original and always has a different sentence structure and word choice. Yet no matter how different from the original, a paraphrase must always be cited, because its content is not original to the author of the paraphrase (Student Judicial Services Center, University of Texas, no date).

| Text Citations Example #2: A paraphrased idea | List author and the date in parentheses at the end of the relevant sentence.

Another way this idea might have been cited is to mention the author directly followed by the date in parenthesis.

|

B. Graphics Citations

In the same way that you may quote and acknowledge limited passages of published text, you may also include illustrations created by others in your assignments. However, works produced by others included in your assignments without acknowledgment are considered to be plagiarized. What constitutes proper acknowledgment for graphics? That depends on the affiliation of the author(s).

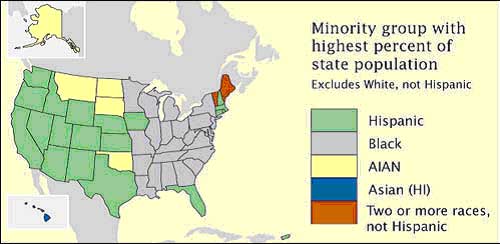

Public domain graphics: Any illustration produced by an employee of an agency of the U.S. government is said to be in the "public domain"—meaning that it is not subject to copyright, and can be reused without permission. Students should acknowledge such works, however, with the names or affiliations of the authors and the publication date, as shown in Example 1 below. Full citations should follow in the list of references at the end of your report.

|

Graphics Citations |

Choropleth map showing nominal-level data.

Brewer and Suchan, 2001

|

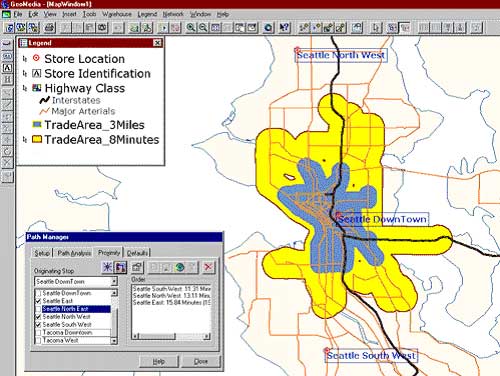

Copyrighted graphics: Any illustration not produced by an employee of an agency of the U.S. government is protected by copyright law. In general, copyrighted illustrations should only be used with authors' written permission. A provision of copyright law called "fair use" permits reuse of copyrighted illustrations for strictly educational purposes, however. (Learn more about fair use from Stanford University Libraries ). In the context of your studies at Penn State, you may reuse copyrighted illustrations without permission, provided that you include in your caption a parenthetical citation with the names or affiliations of the authors and the publication date. Additionally, you must acknowledge the authors' copyright, and state that you have used the illustration for educational purposes only. Full citations should follow in the reference list at the end of your report.

| Graphics Citations Example #2 —Copyrighted source. |

Trade areas defined by 3 miles travel distance (blue) and 8 minutes travel time (yellow)

Francica, 1999. ©1999 Geodezix. All rights reserved. Reproduced here for educational purposes only.

|

C. References

At the end of your report, you must list the full bibliographic citations of the works you have used. The list should be alphabetized by author's last name and references should include the following:

- Author(s) name(s)

- Publication date

- Publication title

- Editors (if publication appears in an edited collection)

- Edition title and number (if applicable)

- URL (if applicable)

- Date retrieved (for Web publications)

- City, State and Name of publisher (if applicable)

- Page number (for quotations from printed sources)

D. Regarding online sources

Websites have become a popular source for research. However, unlike printed material, webpages change frequently, and a source that is available may at some future point disappear. One solution we can suggest, which is purely optional, is WebCite®.

What Is WebCite ®?

Web pages cited in scholarly works are susceptible to the problem of "link rot"—the process by which the links on Web pages become unavailable for various reasons. To prevent readers from accessing Web citations only to find a “404: File Not Found” response, authors and publishers may use a free, non-profit archiving tool called WebCite®. WebCite® permanently archives Web pages and Web sites to ensure that when they are accessed they appear exactly as the citing author originally saw and used them, even after the original link has expired. Learn how WebCite® works.