Maps and the Geospatial Revolution

Maps and the Geospatial Revolution

Open Educational Resources

Now available for self study or re-use in your classes - the Maps MOOC [1] offered on Coursera is now offered as an Open Educational Resource by Penn State.

Since 2013, Maps and the Geospatial Revolution has been taught many times, reaching more than 150,000 learners from around the world on Coursera.

Now the course content and assignments are offered here for free for anyone to use, at any time, to support their own learning or to help them teach others about mapping and GIScience.

Want to go deeper? Penn State offers award winning online GIS, GEOINT, Geodesign, and Remote Sensing programs - check them out at the GIS program home page! [2]

Course Overview

About the Course

The past decade has seen an explosion of new mechanisms for understanding and using location information in widely-accessible technologies. This Geospatial Revolution has resulted in the development of consumer GPS tools, interactive web maps, and location-aware mobile devices. These radical advances are making it possible for people from all walks of life to use, collect, and understand spatial information like never before.

This course brings together core concepts in cartography, geographic information systems, and spatial thinking with real-world examples to provide the fundamentals necessary to engage with Geography beyond the surface-level. We will explore what makes spatial information special, how spatial data is created, how spatial analysis is conducted, and how to design maps so that they’re effective at telling the stories we wish to share. To gain experience using this knowledge, we will work with the latest mapping and analysis software to explore geographic problems.

This class has been taught three times on Coursera [1] in a Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) format. More than 100,000 learners from around the world have enrolled in the class over three offerings since 2013. This site provides the primary content of the course as Open Educational Resources for anyone to use for self-study, adapt for their own teaching, or otherwise re-use under a Creative Commons License.

Note:

This course content is provided as-is. It's a free resource that you may use and re-use under a Creative Commons License. We cannot provide service or support for anyone who uses it, sorry.

Course Overview

Lesson One: The Geospatial Revolution; highlighting the massive changes in geospatial and mapping technology in recent years and their impact on people from all walks of life.

Lesson Two: Spatial is special; an exploration of spatial thinking and geographic thought to provide the context necessary to understand the underpinnings of the Geospatial Revolution.

Lesson Three: Spatial data; how spatial data is created, what makes it different from other types of information, and how it is managed using new technologies.

Lesson Four: Spatial analysis; basic techniques for solving geographic problems that take spatial relationships into account.

Lesson Five: Cartographic design; fundamentals necessary to design great maps to tell compelling stories about geographic patterns.

Recommended Background

No background is required; all are welcome. If you're already a Geospatial Guru, then you might find this class a bit basic, in which case I hope you'll consider taking the online courses [3] that we offer at Penn State.

Suggested Readings

No readings aside from the course content are required, but students are encouraged to explore the Nature of Geographic Information [4] and the Geographic Information Science & Technology Body of Knowledge [5].

Course Format

The class consists of short lecture videos, which are 5-10 minutes in length, as well as written and graphical content to cover key geospatial concepts and competencies. Each lesson features a hands-on lab assignment using ArcGIS Online [6] using their free public account option (no downloads or purchases required).

FAQ

- What resources will I need for this class?

- For this course, all you need is an Internet connection and the time to watch lectures, read course content, complete lab assignments, and discuss your lab work with your peers. You do not need to buy or download any software.

- What will I learn if I take this class?

- You’ll learn how to make maps and analyze geographic problems using the latest tools [6], and you’ll know what makes a good map. You’ll also learn why spatial makes things special, and you’ll understand how Geography permeates nearly everything we do.

- What future learning opportunities will this class prepare me for?

- Students who successfully complete this class will be prepared to continue their education in more advanced GIS and Mapping classes [3].

- What if I need help with this course content or its assignments?

- This class content is provided as-is. Unfortunately, I'm not able to provide individual support for its use and re-use. More than 100,000 students have taken this class since 2013 on Coursera, so most of the kinks have been worked out, but I can't guarantee that its elements won't go stale, that the labs will still work, etc...

- I really need to ask you a question - how can I do that?

- If you really need to send me an email, please send it to maps@psu.edu [7] so that I can keep my inbox semi-reasonable. I will do my best to answer questions there whenever I can.

- Will this class be taught again as a MOOC on Coursera (or elsewhere)?

- Coursera is radically changing how it does courses and I am working on converting the Maps MOOC to adapt to their new model. Teaching a MOOC is a voluntary portion of my job (and most others who teach MOOCs), so it's important to understand that what my day job expects from me vs. what people want me to do for free are often incompatible with one another. I hope to relaunch it soon!

- What's the backstory on how this course was developed? What metrics can you share about how many people passed the class?

- Several research articles on aspects of the Maps MOOC are available at my Google Scholar [8] and ResearchGate [9] profiles.

- Where are the quizzes and exams?

- I haven't included those here, as I'd like to reserve the ability to use those assessments in future runs of the MOOC and other classes I may teach.

Technical Requirements

For this course, we recommend the minimum technical requirements outlined in Technical and Communication Requirements [10]. If you need technical assistance at any point during the course, please contact the Technical Support [11] (for World Campus students) or the IT Service Desk [12](for students at all other campus locations).

Internet Connection

Access to a reliable broadband Internet connection is required for this course. A problem with your Internet access may not be used as an excuse for late, missing, or incomplete coursework. If you experience problems with your Internet connection while working on this course, it is your responsibility to find an alternative Internet access point, such as a public library or wireless hotspot.

Mixed Content

This site is considered a secure website, your connection is encrypted. We do, however, link to content that isn't necessarily encrypted. This is called mixed content. By default, mixed content is blocked in Internet Explorer, Firefox, and Chrome. This may result in a blank page or a message saying that only secure content is displayed. Follow the directions on our Technical Requirements page [10] to view the mixed content.

Equations

This course must be viewed using one of the following browsers: Firefox (any version), Safari (versions 5.1 or 6.0), Chrome (0.3 or later), or Internet Explorer with the MathPlayer PlugIn (link is external) [13]. If you use any other browser, there will be pages containing equations that do not render properly. If you need technical assistance at any point during the course, please contact the Outreach Helpdesk (link is external) [14] (for World Campus students) or the IT Service Desk (link is external) [12] (for students at all other campus locations).

Course Copyright

All course materials students receive or to which students have online access are protected by copyright laws. Students may use course materials and make copies for their own use as needed, but unauthorized distribution and/or uploading of materials without the instructor’s express permission is strictly prohibited. University Policy AD 40, the University Policy Recording of Classroom Activities and Note Taking Services addresses this issue. Students who engage in the unauthorized distribution of copyrighted materials may be held in violation of the University’s Code of Conduct, and/or liable under Federal and State laws.

For example, uploading completed labs, homework, or other assignments to any study site constitutes a violation of this policy.

Accommodations for Students with Disabilities

Penn State welcomes students with disabilities into the University's educational programs. Every Penn State campus has an office for students with disabilities. The Student Disability Resources (SDR) website provides contact information for every Penn State campus: Contacts for Disability Resources at all Penn State Campuses (link is external) [15]. For further information, please visit the Student Disability Resources (SDR) website (link is external) [16].

To receive consideration for reasonable accommodations, you must contact the appropriate disability services office at the campus where you are officially enrolled. You will participate in an intake interview and provide documentation, see Applying for Services from Student Disability Resources (link is external) [17]. If the documentation supports your request for reasonable accommodations, your campus’s disability services office (link is external) [15] will provide you with an accommodation letter. Please share this letter with your instructors and discuss the accommodations with them as early in your courses as possible. You must follow this process for every semester that you request accommodations.

Reporting Bias-Motivated Incidents

Penn State takes great pride to foster a diverse and inclusive environment for students, faculty, and staff. Acts of intolerance, discrimination, or harassment due to age, ancestry, color, disability, gender, gender identity, national origin, race, religious belief, sexual orientation, or veteran status are not tolerated (Policy AD29 Statement on Intolerance (link is external) [18]) and can be reported through Educational Equity via the Report Bias webpage (link is external) [19].

Military Personnel

Veterans and currently serving military personnel and/or spouses with unique circumstances (e.g., upcoming deployments, drill/duty requirements, disabilities, VA appointments, etc.) are welcome and encouraged to communicate these, in advance if possible, to the instructor in the case that special arrangements need to be made.

Connect Online with Caution

Penn State is committed to educational access for all. Our students come from all walks of life and have diverse life experiences. As with any other online community, the lack of physical interaction in an online classroom can create a false sense of anonymity and security. While one can make new friends online, digital relationships can also be misleading. Good judgment and decision-making are critical when choosing to disclose personal information with others whom you do not know.

Author Information

318 Walker Building / 430 EES Building

The Pennsylvania State University

University Park, PA 16802

Email: maps@psu.edu [20]

Homepage: http://sites.psu.edu/arobinson [21]

Twitter: @A_C_Robinson [22]

Availability: E-mail is always the best way to get in touch with me. If you contact me by phone, know that I have two offices here at PSU and only one of them has the phone, so I have to be there to see voicemail messages I might have.

About Me:

Hi! I'm Anthony Robinson, Assistant Professor of Geography and your instructor this term for Planning GIS for Emergency Management. I serve as the Director for our Online Geospatial Education programs here at Penn State, and I split my time between research with the GeoVISTA Center [23] and online education for the John A. Dutton e-Education Institute [24]. My research work focuses closely on design issues with GIS and Geovisualization. I work with end-users and developers alike to help shape new tools and systems for a variety of application areas. I conduct experiments with users to develop design guidelines and to evaluate prototype tools. I also develop design proposals for new systems. Since I started working at Penn State in 2003 I have worked on projects for epidemiology, crisis management, and intelligence analysis domains. My research portfolio [25] is available if you'd like to see some examples.

I have a very strong passion for cartography, and I teach resident courses in cartographic design in addition to this class and GEOG 583 for our MGIS program. Outside of work, I've got plenty to keep me busy. My wife and I have a daughter who likes to break everything in our house. I have a problem collecting hobbies. Among other things, I travel as much as possible, I'm a photographer [26], I have a home studio where I record guitar and drums, I love cooking, I am an airliner [27]/airline fanatic, and I always want to go fishing. Fast cars [28] that make noise are also a passion of mine.

This course content was first presented in 2013 as a Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) on the Coursera [1] platform. Since 2013, the course has been taught three times, reaching more than 100,000 learners from around the world. The purpose of this site is to share the content and assignments from this MOOC to a wider audience who are now free to use and re-use this material under a Creative Commons License.

Cheers,

Anthony

Lesson 1: The Geospatial Revolution

Lesson 1, Lecture 1

Please watch the Lesson 1, Lecture 1 video (5:38):

Okay, let's get started. This is Lecture 1 from Lesson 1.

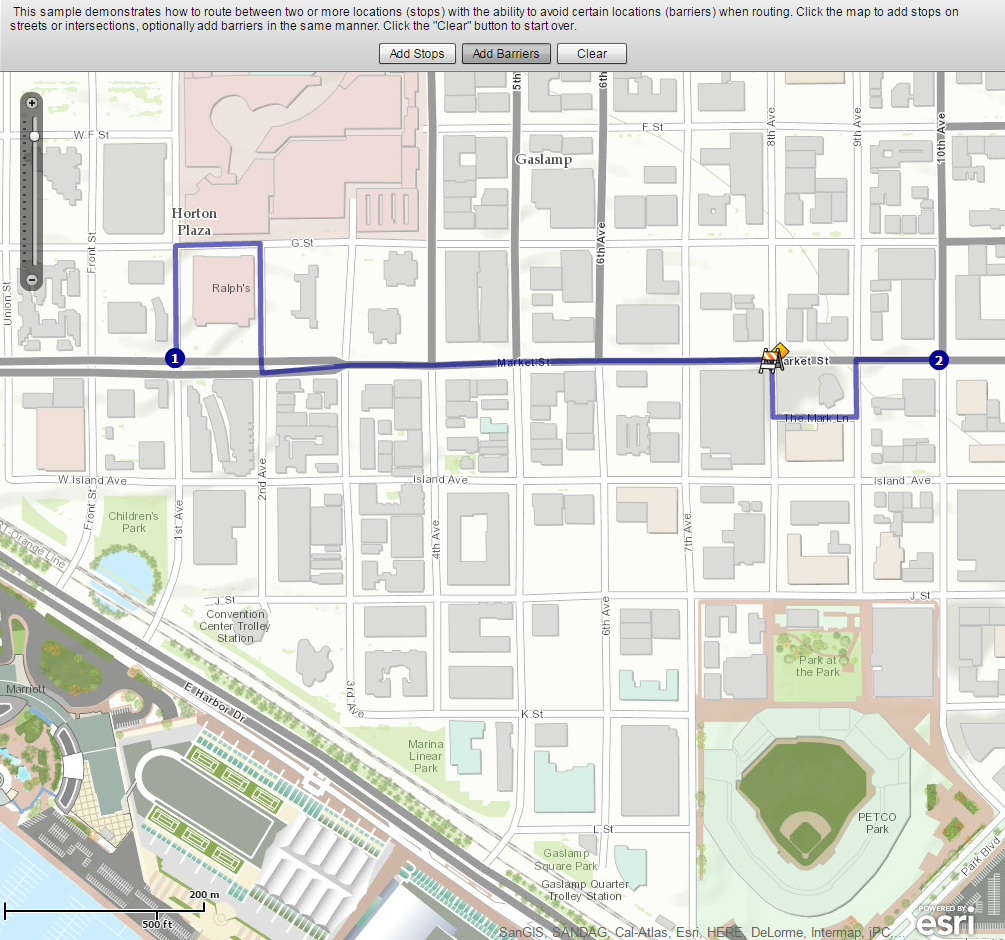

So I think the geospatial revolution is transforming how we do three major things. One of them is how we navigate, how we get from point A to point B. How we make decisions using geography. And how we share stories about what we do everyday.

Maps are now interactive, as opposed to static. We don't have to go to a bookstore anymore to buy something. You gotta plan way ahead for a trip or anything like that. And maps are now embedded in almost every single thing we do. So there's new technologies that have made spatial information more widely accessible like our phones, laptops, tablets all that kind of stuff. But it's also new science, new geographic science, that's made it possible for us to actually use spatial information in new and more powerful ways. So I'm going to talk about all three of these aspects that use spatial revolution today. So how we navigate is one of the major things that I think has transformed. If you think about even what, what someone like my daughter, who's a year and half old now, what she expects to have available at her fingertips now in terms of navigation is completely different than even someone born in 1980 like me. when I was born you know, the way you get from point A to point B is by already, already knowing the route somehow, having done it yourself. Or you go to bookstore, buy a paper map, hopefully they have one for the place you're going, and then you navigate that way. Or you stop and ask for directions, which is kind of hard and awkward to do.

Now my daughter for example, is born into a world where that's almost an insane notion to have to depend, depend on static technology like that. And for someone like her, her entire life is going to be filled with these digital affordances digital maps that come wirelessly to a device and tell you exactly where to go. So even the time it takes to plan a trip is now completely different than it was about ten years ago, for most people, assuming that you have these devices, right? and we're already kind of annoyed that our technology isn't even perfect yet, right? It's reached the point where it's pervasive at the level that we kind of complain about the free stuff that helps us navigate almost anywhere in the world with almost no notice. and most of the time flawlessly, right, whenever there's a little problems with it we sort of get a little bit upset about it. So I think that's revolutionary that it's now pervasive that anybody can navigate almost anywhere with very little technical ability, right? You can just fire up web browser and use your phone, do it.

Beyond just navigation though, I think what's revolutionary is, is now how we use geography to make better decisions. So, even simple decisions like the wonderful, age-old spousal argument around, where should we eat dinner tonight, are now enabled made easier by geospatial technology, or in some cases, harder because we have more options, right? So my wife and I want to know, want to figure out where we're going to go eat. And that could be like, well, I want to have Chinese food and she wants something with bacon in it, and we need to know where is the nearest restaurant that serves Chinese food with bacon in State College, right? We want to, we want to know whether or not it's open. What's the traffic like between here and there. And we can actually get an answer to that really quickly and help us make a decision. it doesn't actually solve the argument, right? It just kind of makes it a little bit longer in some cases. But, those kinds of decisions are now possible because of geography as well. It's not just navigation, it's actually knowing what to do, right? How, how to do things next. And that's a really mundane, silly kind of example, but the cutting edge of technology in science and geography is focused on way harder questions, such as what parts of this coast should we evacuate for the hurricane that's coming. And that's a way more difficult problem than one where the answers are not quite as clear yet. But there's a lot of effort in the science of geography right now to try to figure out questions like this. And we're going to cover a lot of that stuff in this class.

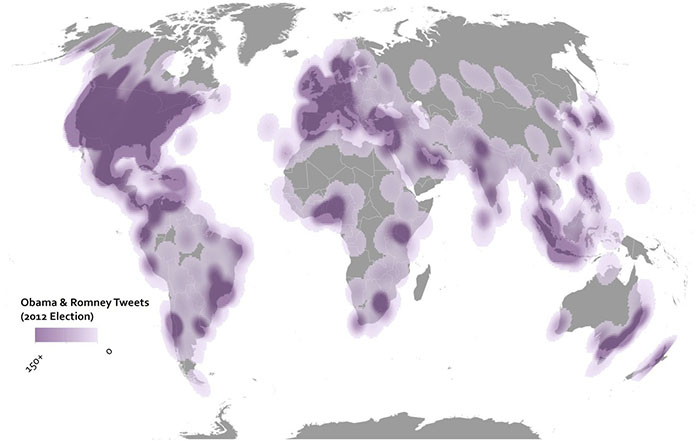

The third area that I think is quite revolutionary now is the geography can be used to ground the stories of our lives. So pictures, for example, can be really easily geotagged to make maps of your memories. You can, you can add a place to where you did something. you can add a place to your tweet, for example, and say that I talked about this wonderful coffee I had at the coffee place that I bought the drink, right? You can share all these crazy, mundane things. You can start to tell stories about your lives that are grounded in where exactly they happened. And if you think about even ten years ago, this was an extremely cumbersome thing to do. It may have been possible then with the technology that existed, but it was not easy and it certainly wasn't accessible to lots of people. And 20 years ago, it really wasn't even possible, to be honest. I mean there were maybe some people who had at the extreme cutting edge who were using lots of devices to try to do this kind of geotagging, but it certainly wasn't even a little bit common at that point. So I think that's a really transformative thing. So here's an example to look at. this is Flickr, a big popular photo sharing site. And what I've done here is I'm going to capture the priceless memory of my daughter crying during a time when she was getting a bunch of presents, I think this was at Christmas. And I want to ground this in the geographic context in where it happened. So I've assigned a location for it in our neighborhood at the house the place where this happened. And, and now I have this memory attached to a map. And so, for the rest of her life, whenever she wants to go to see exactly this time when she was so upset, so unhappy, and and really couldn't understand how many presents she was getting and, you know, her, her emotional turmoil was connected to this place. I want her to be able to relive that memory in the same depth and richness that I did, when it first happened, right? So I think that telling stories with with maps now is one of the most amazing things that's possible from geospatial revolution.

Look at the great stuff we can capture like this.

The Geospatial Revolution

I think the Geospatial Revolution involves major transformations in the way we do these things:

- How we navigate

- How we make decisions

- How we share stories

What’s unique here is that concepts of space and technologies designed to leverage location information have made huge advances in all three of these areas possible. The past decade alone has seen a complete paradigm shift in how normal people are able to use and think about Geography. It’s not just geeks like me with fancy software and high-tech expensive gear who can make and use maps anymore. And maps aren’t just for naming places or placing pins on the nearest Waffle House, although that’s pretty important too.

How We Navigate

So are we really experiencing a Geospatial Revolution? Let’s use my daughter as an example. Claire was born in 2012. When she arrived, it had already become commonplace for many people to have interactive maps accessible through computers and handheld devices at relatively low cost. In her world, nobody needs to learn how to use a paper road atlas to find their way to Grandma’s house. Instead, directions to and from almost anywhere can be had for free in an instant using easy-to-manipulate tools like Google Maps and MapQuest.

So that’s one way in which personal navigation has been completely transformed. In contrast to Claire, when I was born, it was really important to plan ahead about where you were going (using paper maps, which you had to buy or borrow) or you had to be prepared to take longer, rambling journeys that relied on dead reckoning alone. I still have fond memories of working as the navigator on our family car trips to the beach in South Carolina, spending hours poring over a big paper road atlas that showed only a couple of map scales. When we hit a lot of traffic, I might have to help find an alternate route. Today, we still need to intervene from time to time to find a new way to get somewhere, but it’s as simple as dragging the route around on the map, or telling the GPS to give us another option.

For Claire, by the time she’s ready to drive, I suspect it’s likely that making those alternate route decisions will also be a thing of the past. Our cars will simply know the best way to go given current weather and traffic conditions, and take us there with minimal intervention. We’ll all be a little dumber because we won’t even remember how to navigate the old way. I will be stumbling around an old folks home, dragging a shopping cart behind me filled with dog-eared paper atlases while loudly decrying the downfall of civilization.

Making Decisions

The Geospatial Revolution is much more than just a transformation in how we go from Point A to Point B, however. It’s also about making decisions and analyzing problems using Geography. Let’s consider the age-old problem of deciding where to eat dinner tonight. We’ll assume that we’ve already looked through the cabinets and decided that nothing good was there for us to make, so we’ll need to take a trip. My wife and I are pretty bad at reaching a decision about such matters, and thankfully we can rely on geospatially-enabled stuff to help us reach consensus. Today, we can just fire up Yelp [29] from a phone and ask it to find the nearest restaurant that serves amazing Sushi and also happens to be open on a Monday night. That question can be answered in just a few seconds now, and if we haven’t been there before, we can tap on a little button to tell us how to get from where we’re standing to our reserved table. It won’t help us sort out the personal conflict that arises when I want a sub and she wants tacos, however. That’s what we need Facebook and Twitter for—to gripe about mundane crap and hear what other people think about our mundane crap. But I digress.

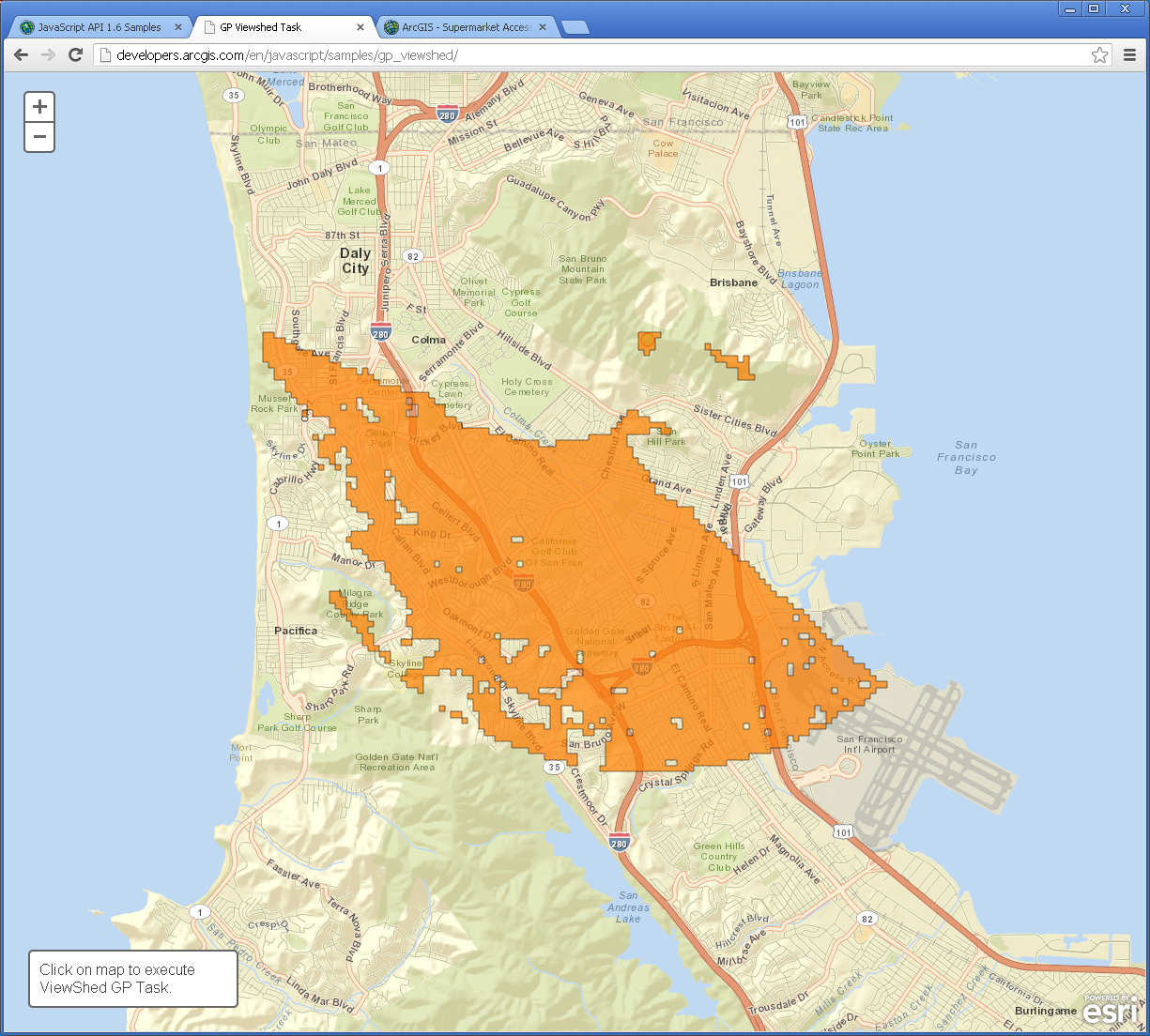

Figuring out where to eat is a pretty simple decision for me to describe. What about making decisions like where to locate the next shopping mall in your home town? How about forecasting the potential for a city to be impacted by natural disasters? What about protecting endangered species? Each of these problems requires one to use and make sense of Geography in various ways. What’s exciting is that the Geospatial Revolution has brought about new sources of data and amazing interactive tools that are capable of helping us make those decisions. In each of the five lab assignments you’ll complete in this course, you’ll gain experience evaluating Geographic problems like these and you’ll see how powerful (and how complicated) geospatial analysis can be. You’ll also lose weight, feel happy about yourself, and maximize your earning potential!

Sharing Stories

In less practical, but more engaging terms, we’re also able to use Geography now to share our personal stories in much richer ways. I’m a big photo nerd (and map nerd, and airplane nerd, and… basically just a many-faceted nerd) and even if you’ve barely been paying attention for the past 10 years, you’ve no doubt seen photo sharing sites like Flickr and Picasa. Both services allow you to easily Geotag your photos. Geotagging is a form of geocoding, which is the term used to describe the assignment of location information to a data record. After you upload your pictures to Flickr, you can say where they were taken by either assigning place information manually (“tagging” a photo of the Eiffel Tower by saying it was taken in Paris) or by uploading coordinates that were captured by a GPS device that you used to track your movements (so you can be much more specific about the exact spot on the earth where the photo was taken). I bought a new camera recently (a Canon 6D [30]) that has a built-in GPS tracker to assign coordinates to every photo automatically. As I travel, I’m actually making maps. Awesome.

It’s this kind of revolution that allows us to tell stories using Geography much more easily than ever before. In 1999 if I wanted to make a map that showed all of the places where I stood and took pictures on the epic 5-week trip I took across Bolivia, Peru, and Ecuador, I would have had to buy and carry with me a heavy, cumbersome Global Positioning System (GPS) receiver and develop my own workflow for scanning my photos from film and digitizing everything into Esri’s ArcView 3.0 Geographic Information System [31] (GIS) software. While it was possible, it would have been incredibly difficult to pull off, and it was certainly the type of thing that was well out of reach of most normal people who just want to document their cool travel experiences. If we went back another ten years to 1989, even that clumsy process would have been impossible to imagine unless you happened to also run a huge spy agency.

Today, however, I could actually go back and scan those photos, and just drag them onto the map in Flickr (assuming I remember where I took the pictures… but just play along with me). I’ve shown that process here using the current Flickr interface and a picture of my daughter crying which I thought really needed to be on my personal map [32].

Lesson 1, Lecture 2

The Changing Nature of Place

It may seem like the basic attachment of location information to anything and everything reveals a relatively stable future for Geography and Geospatial technology. All we have to do is Geotag everything and we’re done with this Geospatial Revolution thing, right? I don’t think it’s that simple, because the enormous potential of location-enabled everything faces similarly huge barriers for people who want to make sense of interconnected and massive spatial data sources. Moreover, the super-simple common format for a location—one set of coordinates on the Earth—completely fails to describe the richness of Geography.

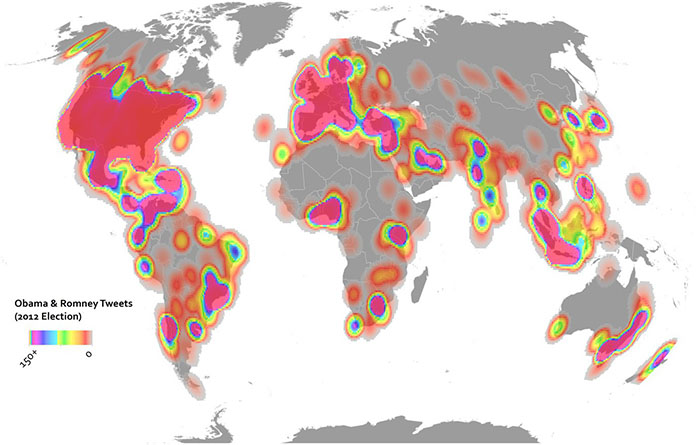

For starters, it’s often impossible to assign a single relevant location to an observation. Let’s even take something as constrained as a Tweet as an example. You only have 140 characters on Twitter to tell your story, so not much can happen here with locations, right? Wrong. There are multiple relevant locations with any Tweet. Where is the Twitter user from? Where were they when they Tweeted their message? What about the message itself? Does it contain references (explicit or implicit) to locations? We’ve done some research [33] on this area at Penn State and found that many Tweets contain references to many different locations. So how do we show that on a map? Which ones are the most important or explanatory? Like most complex analytical problems, the answer may depend a lot on what you’re trying to learn from that information. Let’s say you’re working for a crisis management organization and you want to monitor what’s happening on Twitter to identify emerging concerns in the wake of a major disaster. What types of locations would you want to see? Could you use location information to establish a basis for comparing the credibility of a particular report? How would you show millions of these reports on maps that could be used by a normal human being who isn’t just studying this stuff after the fact?

In the more benign example here, which places are relevant to this important discussion on where to find a delicious Cinnabon cinnamon roll? The United Kingdom, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Austin are all mentioned here explicitly. But what about the hometowns for each of these folks, or the place where Cinnabon is headquartered (Yumtown at the corner of Godhelpme Ave. and Gimmeicing Lane)?

While we’re at it, let’s talk about defining locations more broadly as well. Until now I’ve emphasized a single point in space as a location. Geographic locations can include well-defined formal regions like states and counties, natural areas like watersheds and mountain ranges that can sometimes be formally defined by their observable features, and ill-defined cultural regions like neighborhoods. I live in a place informally known as Happy Valley. It’s not just the city of State College or its surrounding townships and boroughs. It includes space outside of those formal areas, and it cannot be defined precisely despite the fact that it clearly corresponds to a place on Earth. We still have a lot to learn about how to collect people’s conceptions of these sorts of places and use them on maps. The example here by Andy Woodruff [34] and Tim Wallace [35]at Bostonography.com [36] shows how people in Boston conceive of their city’s neighborhoods. It’s pretty blobby and imprecise, and parts of the map are empty. This is a much more faithful representation of what we can actually know about these types of places than the neat and tidy borders we can define for legal boundaries.

What is Geography?

Geography is the science of place and space [37]. It involves the study of spatial (all stuff exists somewhere in space) phenomena of all kinds. I’m pleased to say it’s much more than just naming places on maps. I fly a lot, which means I often have to explain to someone sitting next to me that I’m a Geographer. This prompts one of several typical responses:

- Oh cool, I have a cousin who’s a Geologist!

- Haven’t all of the maps already been made?

- Oh neat, I have no idea what that is!

- Wow, that is so sad!*

*full disclosure, this didn’t happen to me but it did happen to a map nerd friend of mine who said what she did for a living to a guy hitting on her at a bar. It prompted this response.

When I talk about Geospatial stuff in this course, I’m referring to information and technology that has location as one of its key components. So Geography is the science of understanding places and spaces, while Geospatial refers to the data and technologies that allow one to explore Geographic problems. Geospatial is always a modifying term – so I’ll talk about Geospatial information, or geospatial systems, or geospatial bacon, never just “Geospatial” all on its own. This is somewhat simplified, and Geographers are infamous for having almost no ability to reach consensus on how we define ourselves or what we do, but I’ve given it my best shot here.

Maps To Tell Stories, Maps To Provide Context

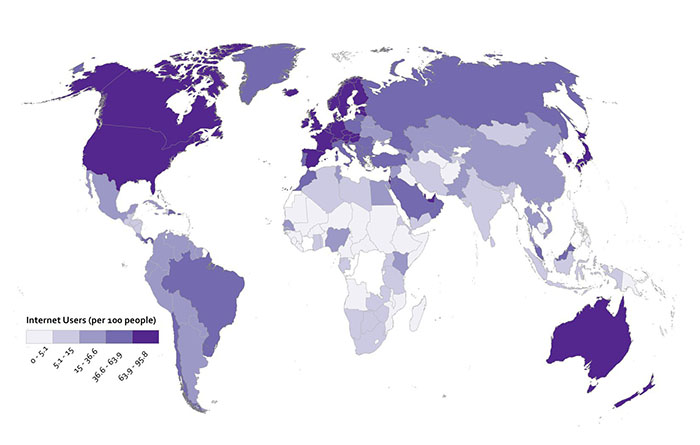

There are two major categories of maps. Thematic maps are used to showcase geographic data observations. Thematic maps are almost always associated with storytelling of one kind or another. For example, let’s assume I have a dataset showing the proportion of U.S. citizens who are currently talking about something inane on their cellphones. This hypothetical data might be collected at the county-level, and I’d want to tell a story with my map about which places in the U.S. have the most insipid talkers. The pattern of those observations by county would allow map readers to understand the geographic distribution of those folks, and begin to formulate hypotheses about their causes (places with lots of teenagers, middle-aged men roaming airports, etc…).

Or you could have a much more serious example, like the one shown below. This map shows the proportion of households in the Lower 48 United States that are headed by women.

Now you’re probably wondering about the kind of maps you thought I’d start with here. Reference maps (also frequently called basemaps) provide the basic Geographic context required to situate other stuff. A good example here would be a Web Map [38] that shows roads, physical, and cultural features. Reference maps are used all the time these days as the backdrops upon which we plop all sorts of digitally-rendered map pins [39]. If you fire up Yelp and search for a nearby place to buy a very large bag of delicious Nacho Cheese Combos at 4AM, you’ll see a bunch of these pins appear on top of a basic, multi-purpose reference map. Designing these map canvases is really hard. To give you a tiny flavor of the challenges here, check out how many named geographic features exist for just one county [40] (select "Pennsylvania" from the state dropdown and type "Centre" into the county field). You should end up with 1177 named features. Now, poke around with the web map example here [41] and pay close attention to which features exist, what they are named, and how they are drawn at different scales. Try zooming in to the area around Grand Canyon in Arizona and see how the labeling and symbols change as you change scales. Computers can’t do this stuff automatically (er… at least not without a lot of human intervention), so there is a huge amount of work that goes into designing these now taken-for-granted reference sources.

The Earth Is Round And Maps Are Flat

That’s really all you need to know, but I guess I need to explain a bit more, huh?

To identify a location for anything, we need to set up a reference system. The one we use most commonly is the geographic coordinate system of Latitude and Longitude. Think of it as an addressing system for the entire planet. It’s really just a grid system, with standard lines of Latitude providing North/South parallels and standard lines of Longitude providing East/West meridians. Latitude varies from +/- 90 degrees from the Equator, and Longitude varies from +/- 180 degrees from the Prime Meridian, which runs through the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, England [42].

Latitude and Longitude coordinates are expressed in either decimal degrees or in degrees, minutes, and seconds. Both methods are useful for different tasks, but it’s a bit beyond the scope of this class and I don’t want you to fall asleep so early in the course.

This is all well and good, but a major problem we have to deal with here is that the Earth is spherical (erm, it’s an imperfect one, so it’s actually an ellipsoid) and we need ways to take stuff off this 3D object and present it in 2D on paper or on screen (since carrying a globe around is pretty annoying). For an illustration on exactly why this is a problem at all, get yourself an orange, draw crude versions of the continents on it, and then try to peel the orange without distorting or tearing the map at all. Don’t do this on top of your iPad or while you’re supposed to be paying attention on a conference call. You’ll notice that it’s very hard to do anything that doesn’t totally ruin the map, and the best you can approximate is something like the image shown here (if you’re really good). Nathan Belz [43] tells a neat little story [44] about what he did to create this example.

This is all a lead-up to tell you that in order to make maps, we have to flatten the Earth using math. The act of making transformations to translate points on a sphere (Lat/Long) to points on a 2-dimensional plane (a map) is called Map Projection. Because math is fancy witchcraft concocted by devious wizards, there are hundreds and hundreds of possible mathematical transformations from the Earth to a map in the form of named Projections. The one you see above is called the Goode Homolosine. I’m personally partial to the Robinson Projection [45], although I unfortunately had nothing to do with its creation.

What you really need to know is that Projections allow you to preserve some, but never all of the basic characteristics of Geographic relationships. Specifically, you can preserve direction, shape, area, distance, or the shortest route between locations. Alternatively, you can choose to preserve none of these attributes and instead focus on a compromise across them (as is done with the Robinson projection and many other World Map projections).

Video Activity

Now that I’ve set things in motion a little, I want you to watch Episode 1 of the Geospatial Revolution video series [46] produced by WPSU at Penn State [47]. This video is 13 minutes long, so it’s a fair bit longer than most of the other videos you’ll watch in this class. I’ll do everything possible to keep the remaining videos short and snappy – but this one is really compelling and has cool dramatic music so I think you’ll be able to hang in there without snoozing.

Mapping Assignment

Introduction

This week, you learned that geography is the science of understanding places and spaces. You also learned that one of the ways people have sought to understand places and spaces is through maps. As you are discovering, part of what the geospatial revolution means is the advent of geospatial technology. Geospatial technology helps us create content that can be changed. In this lab, you will have the opportunity to get started with web mapping.

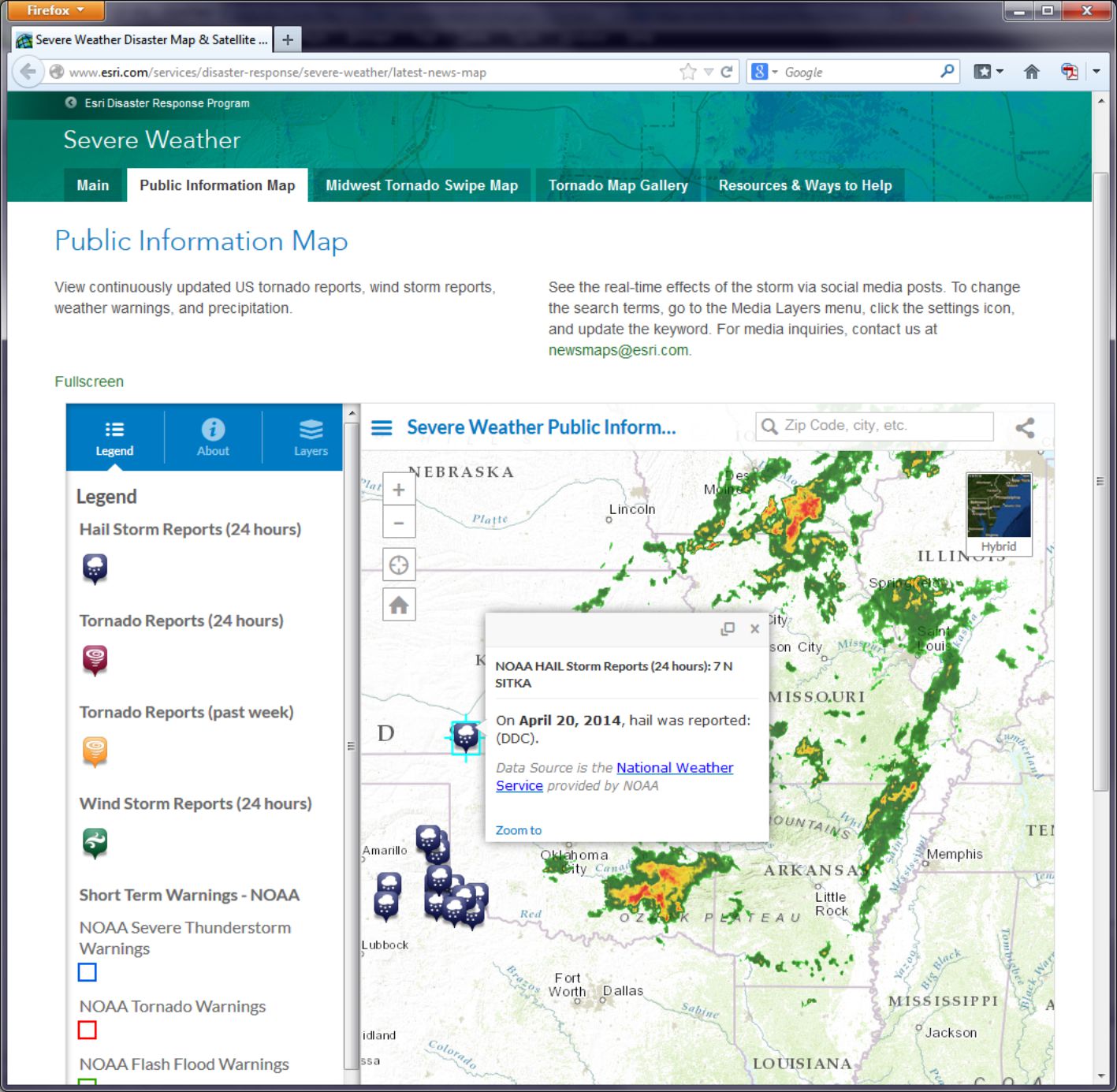

You probably already use cloud-based technologies when you use Google Drive, Facebook, Flickr, or Dropbox, for example. Web mapping is GIS in the cloud. Web mapping includes spatial data in the form of maps, databases, map services, and satellite images, and it also contains tools and functions such as the ability to measure things and to do spatial analysis.

Not all digital maps are dynamic; millions of maps exist in presentations, PDFs, and as static images like the ones I’ve made for this class. But unlike static digital maps, dynamic digital maps can show real-time things like weather, floods, or traffic. Layers of information can be added or subtracted from them so that you can change the map design yourself at will. The scale, colors, symbols, and the way their data is classified can all be changed. They can be embedded into live web pages, changed from 2D to 3D, and formatted for a smartphone. Therefore, they move beyond being simply reference documents (“Where is Uzbekistan? OK, great! Next?”) to being tools of geographic inquiry, used to understand spatial and temporal patterns in order to solve problems.

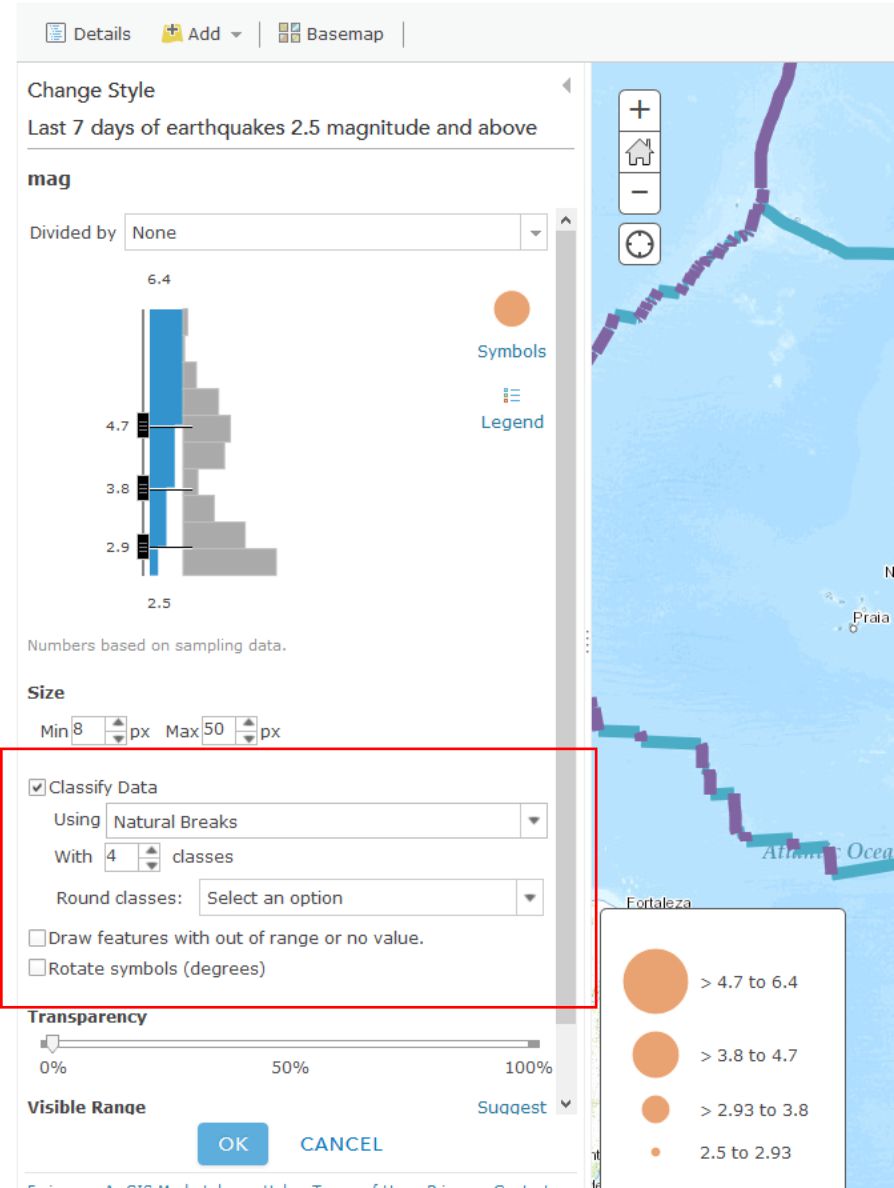

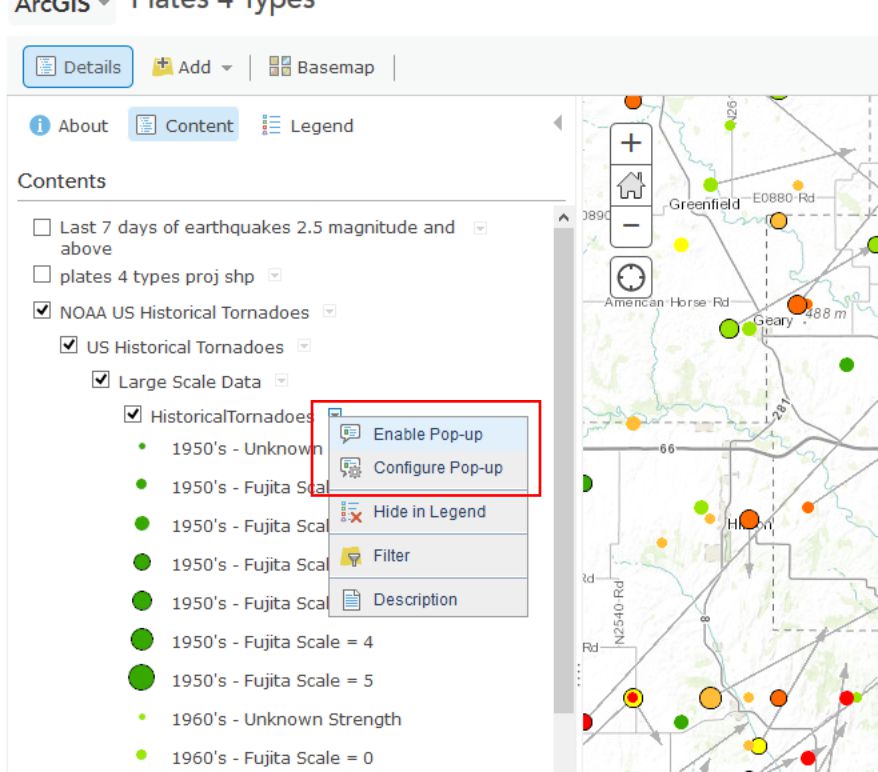

To give you hands-on experience making your own maps and doing spatial analysis, we’ll be using Esri’s (cloud-based GIS called ArcGIS Online [48]). Joseph Kerski works for Esri’s Education Team and has done a ton of great work to develop these labs for you. ArcGIS Online does many of the things a desktop GIS system can do, but it has a much easier learning curve, can be used right in your web browser, and makes it really easy to share interactive maps you make with others. Esri paid me zero dollars to say that and use this stuff in this MOOC and they have been enormously helpful to make sure that you can do awesome stuff in this class using their software.

In addition to tools made by companies like Esri, there is a flourishing community of free and open-source software for doing all things geospatial (see osgeo.org [49] for an overview and live.osgeo.org/ [50] for tools). For the final assignment in this course you’ll have the opportunity to explore an open-source options (like CartoDB [51], for example) or use ArcGIS Online.

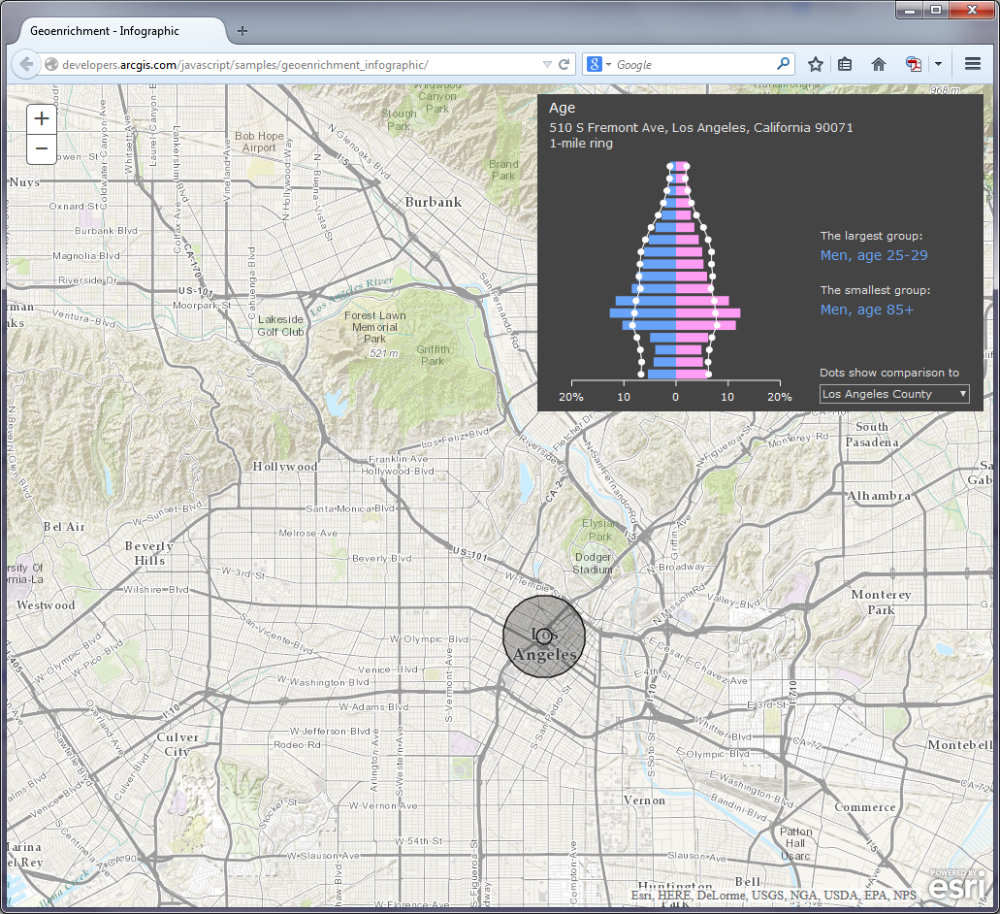

Investigating Global Population and Ecoregions

Have you heard about “big data?" Since they seek to understand the whole world and everything in it, geographers were into big data way before the term existed. With the explosion of datasets of all types, geospatial data abounds as well, at scales from local to global, and across themes ranging from natural hazards, to energy, to water, and geology. For example, in terms of population, not only can you obtain the locations of cities, but the size of those cities, and not only total population counts, but also population density, how population is changing, and characteristics of the population such as age, ethnicity, income, education, life expectancy, and other variables. You can examine the relationship of population to other phenomena, represented as map layers. In this lab, you will examine the relationship of where people have settled to the physical environment. You will also determine how population impacts the physical environment in which it exists.

Before you start using the tools, try to answer the following questions as best you can. You don't need to submit your answers, but you may want to write them down someplace.

- What is an ecoregion? You’ll probably want to fire up your Google to sort this out. That’s what I’d do.

- In what ecoregion do you live?

- What is one factor that influences population density in a given area?

- Describe the population density in the neighborhood in which you work. Make a little note of what you think this is. You’ll need it later in this lab.

Let’s Make a Freaking Map Already

When you’re ready, click here to begin building a map [52]. You may want to open links like these in a new window so that you can switch between the lab instructions and the mapping tools.

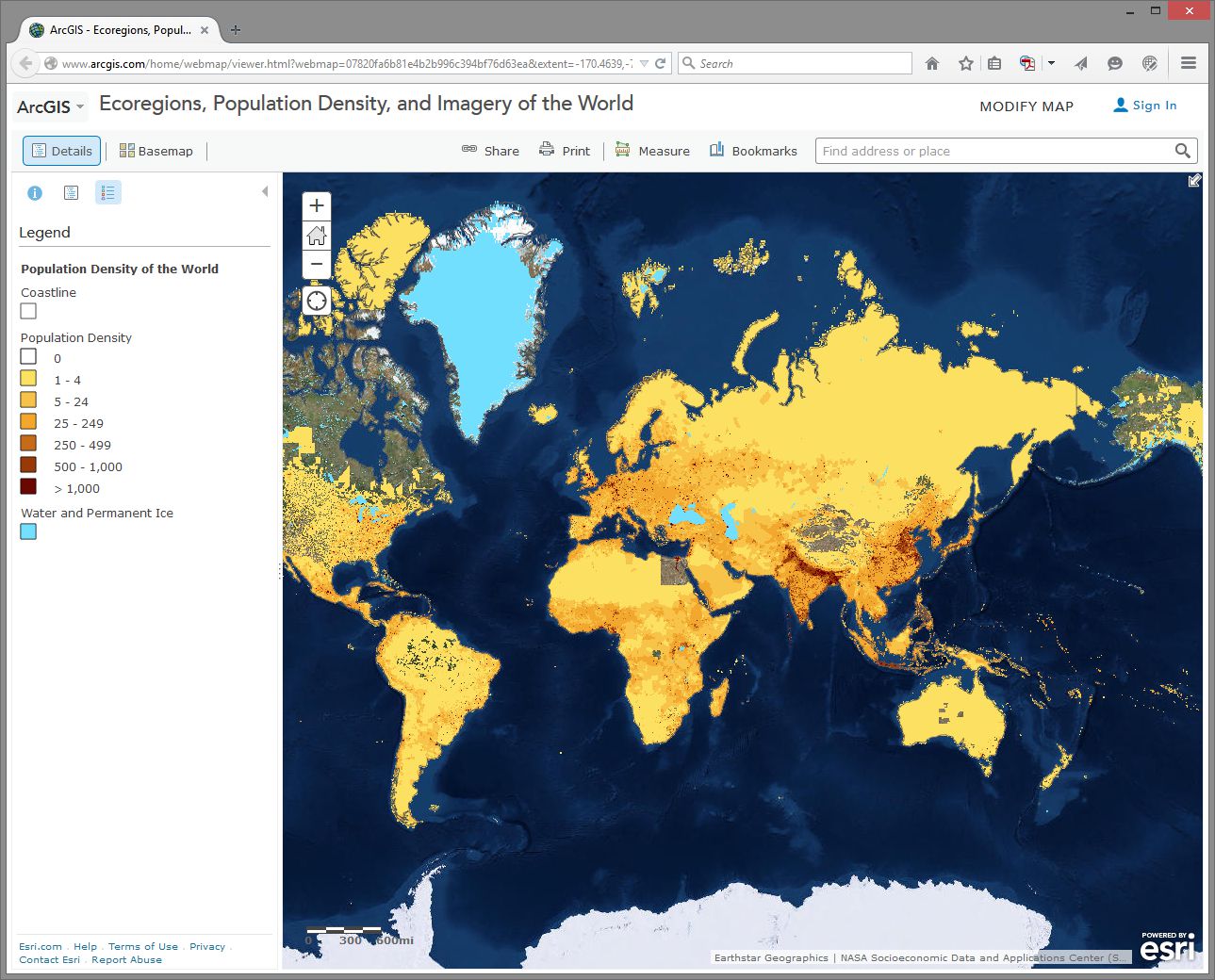

This map was built using ArcGIS Online. First, note that you have the map occupying most of the screen (as it should be!). Second, you have a set of map layers on the left. Third, you have tools—some of which are at the top, and some are available through the list of layers on the left.

This map shows Ecoregions, Population Density, and Imagery. To see these, select “Modify Map” in the upper right of the interface, then click Content above the Legend to see the list of available layers.

Take some time now to explore the About, Content, and Legend buttons directly above the Legend. Get comfortable with what these buttons do. Zoom using the vertical scale bar at the left side of the map—the middle scroll wheel of your mouse if you have one—or by holding the shift key and drawing a box on the map with your mouse. Bookmarks are another way to zoom in or out (change the map scale).

Now use Bookmarks (just left of the search bar at the top) and select World. Show the map legend. Your map should look like this:

How would you describe the pattern of world population density?

Change the Basemap back and forth from Imagery to Terrain With Labels so that you can refer to country and city names that are part of the Terrain with Labels layer.

- As we will discuss later in this course, knowing where data comes from is, to put it into geographical terms, a Very Big Deal, particularly with maps. To start thinking along these lines, examine the “details” of the population density layer by clicking the right arrow next to the layer and selecting Description.

- Who created this data, and what sources did they use?

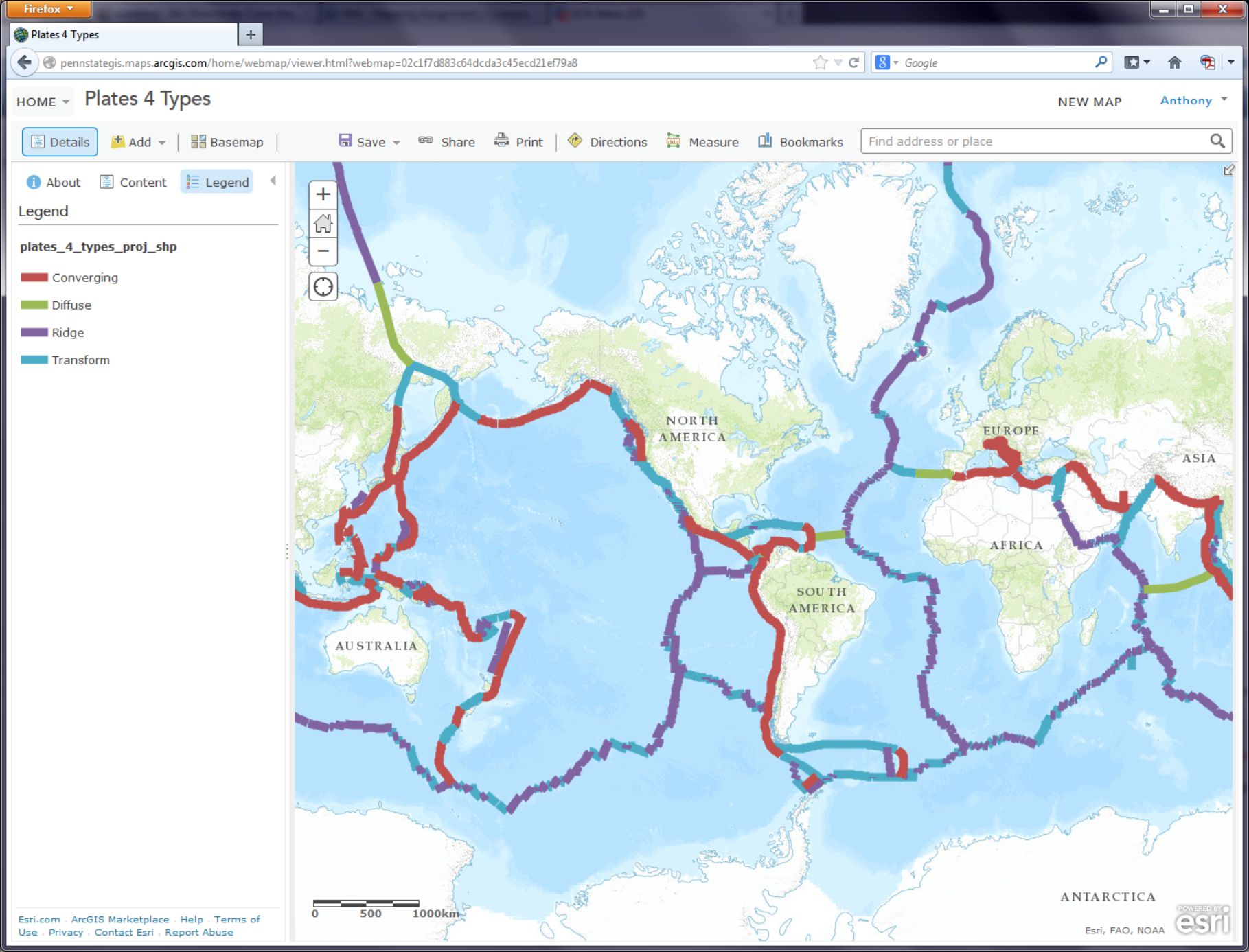

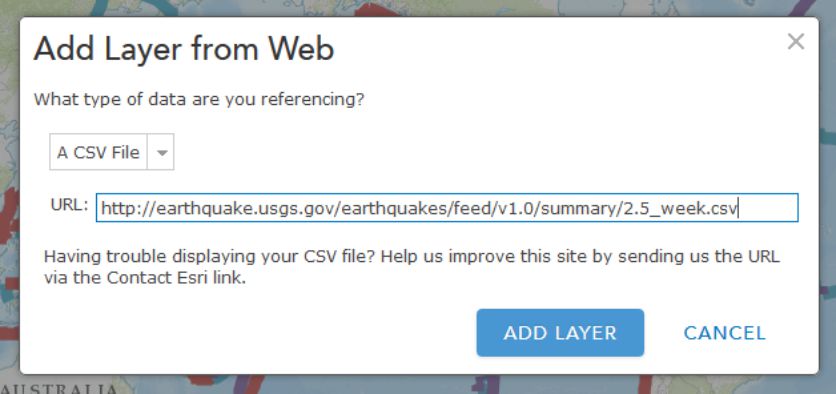

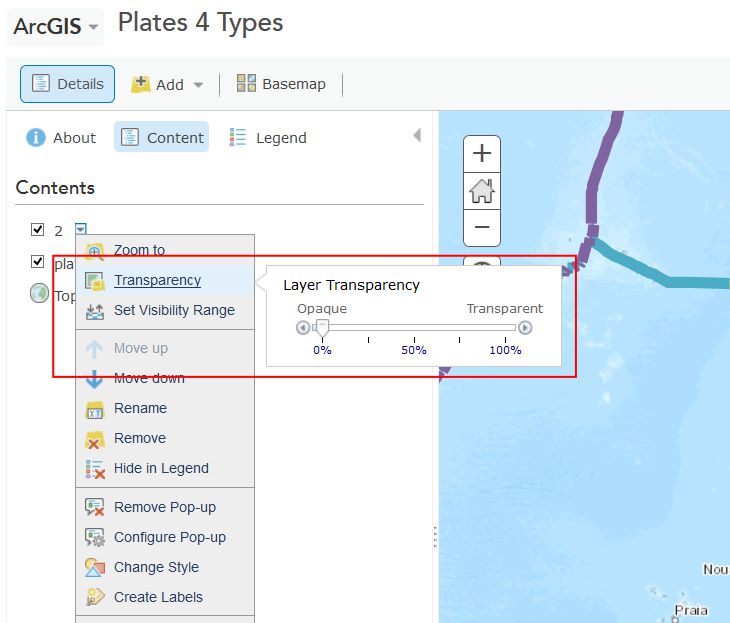

Use Bookmarks and select India-Nepal. Toggle between population density and the imagery base map. Try making the population density layer transparent by clicking on the small right arrow next to the layer name, selecting Transparency, and using the slider bar that appears.

- What is one reason you can think of for the difference between the population density in northern India compared to that of Nepal?

- Use the Measure tool and determine the distance between the area of highest population density in India to the area of lowest population density in Nepal. Be sure to note the distance units you are using (miles or kilometers).

- Switch from the Legend view to the Contents view and turn on the Ecoregions layer. Turn the Population layer on and off and note the predominant ecoregions in the most densely settled regions of northern India. Also, explore the relationship between population density and major rivers. How do you think the dense settlement here may have an effect on the ecoregions of this area?

- Describe the ecoregion and the population density in the region in which you live using the map. How does the population density compare with your earlier observation where you were asked to reflect upon the population density of your area without the aid of a map?

Exploring Population Dynamics (That’s A Lot Of Babies)

Let’s take a deeper look now at how population is changing all over the world and explore what might be driving those patterns.

Use the Add button, then Search For Layers and search for: World Bank Age and Population in ArcGIS Online. Select the one authored by “Intl_User_Community.” Then click the big blue Done Adding Layers button at the bottom to add this layer to your map.

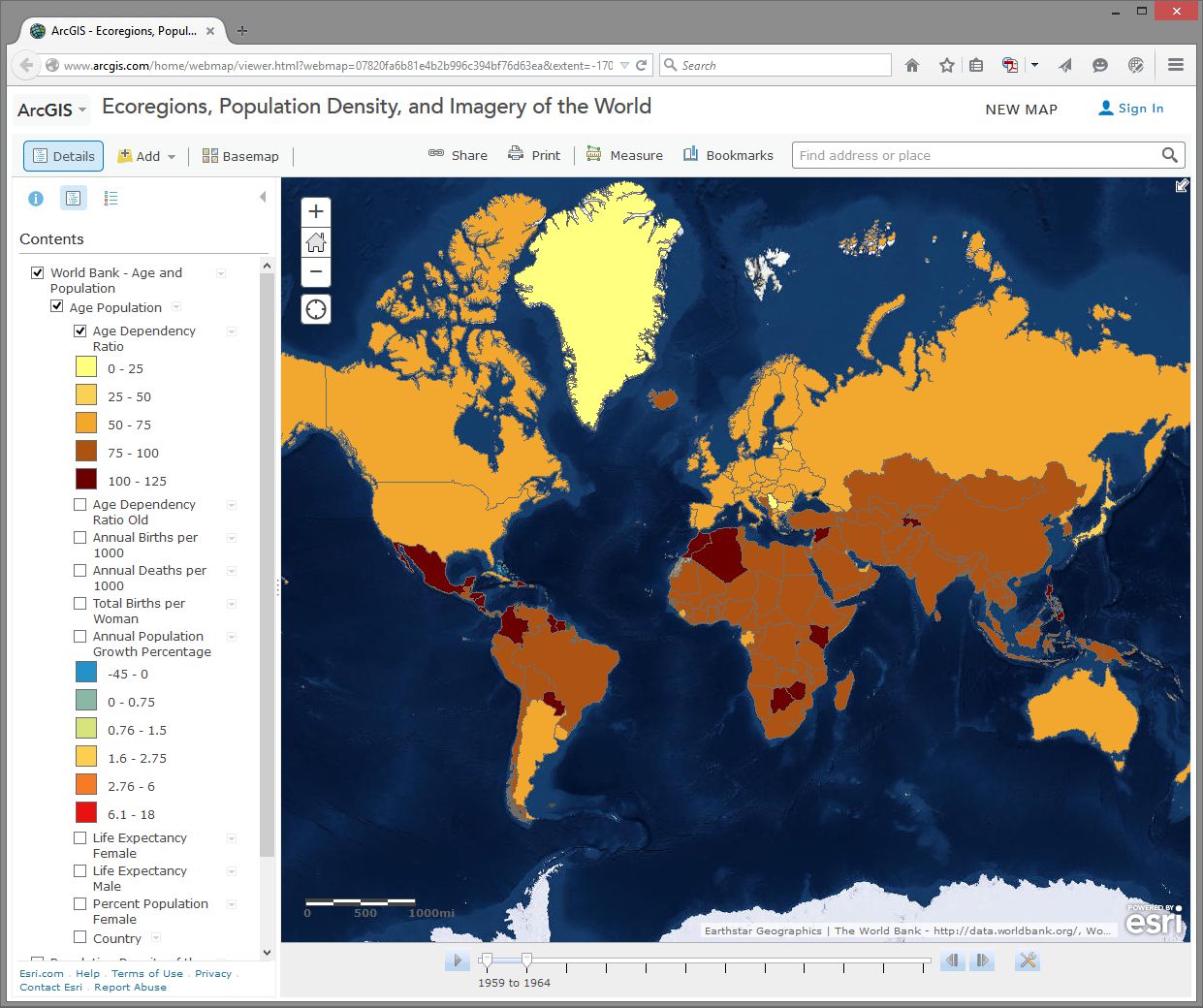

First, select the Content button to show the map layers instead of the legend. Then, expand your newly added age and population layer by clicking on its title and then click on Age Population. You will see that this map is actually a set of 10 layers (ideally, every map should be turned up to 11 though). Uncheck any layers in this set of 10 that might already be selected - we want to start with a clean slate.

Next, select the checkbox for the Annual Population Growth Percentage, show the legend by clicking on the layer name, and note how much the growth rate varies around the world. Make sure that no other layers listed before this one are turned on, since those could obscure the layer you want to see. Now turn on Age Dependency Ratio. Age Dependency Ratio [53] is the ratio of dependents (people younger than 15 or older than 64) compared to folks in the working age population (15-64). Click the Age Dependency Ratio layer name to display its legend. Your map should look similar to the one shown here:

Which statement is correct?

- Countries with a higher growth rate typically have a higher age dependency ratio.

- Countries with a higher growth rate typically have a lower age dependency ratio.

Why do you suppose the growth rate and age dependency ratio are related in the way that you've indicated above? The percentage of working age population is also known as the “dependency ratio,” because this number represents how much of the population (young and old) that is dependent upon the working age population.

- What impact do you think a high population growth rate has on a country?

Note that these data sets go back in time—to 1960 in some cases. My parents were born in 1960. Every photograph automatically looked like an Instagram back then. You can use the arrows in the popup boxes to access the different years. You can use the slider bar under the map and the play button to animate the data over time, or slide the marker all the way to the right to 2014 to display the most recent data. So with these maps you can examine not only the spatial dimensions, but also the temporal ones.

Pick a country that interests you and examine the growth percentage and life expectancy in that country over time. If you’re a rockstar student you’ll share something you discovered with your peers in the discussion forums. You can always click on the Share button to get a link to embed in your post.

- Recall your recent reading about map projections. This map uses the Web Mercator projection. How are the areas near the North and South Pole shown on this map?

- How does the projection that this map is using affect your interpretation of what you are studying?

Geodemographics – Having Fun With Stereotypes

The statistics you are examining about population tell only part of the story about the people in those places, of course. People live and behave in ways that might be described with a combination of variables, not all of which are captured on census surveys. One of the ways to measure this aspect of demography is through the creation of a variable that captures a “lifestyle” by neighborhood. It is this variable that marketing folks often use to send you forty catalogs of gourmet food products and coupons for discounted hair transplant surgery (wait - you mean that’s just me?). Marketing folks use this stuff to help determine what is stocked on your local stores’ shelves, what types of cars or bicycles or breakfast sandwiches are sold in your area, what sorts of movies are shown, and a whole lot more.

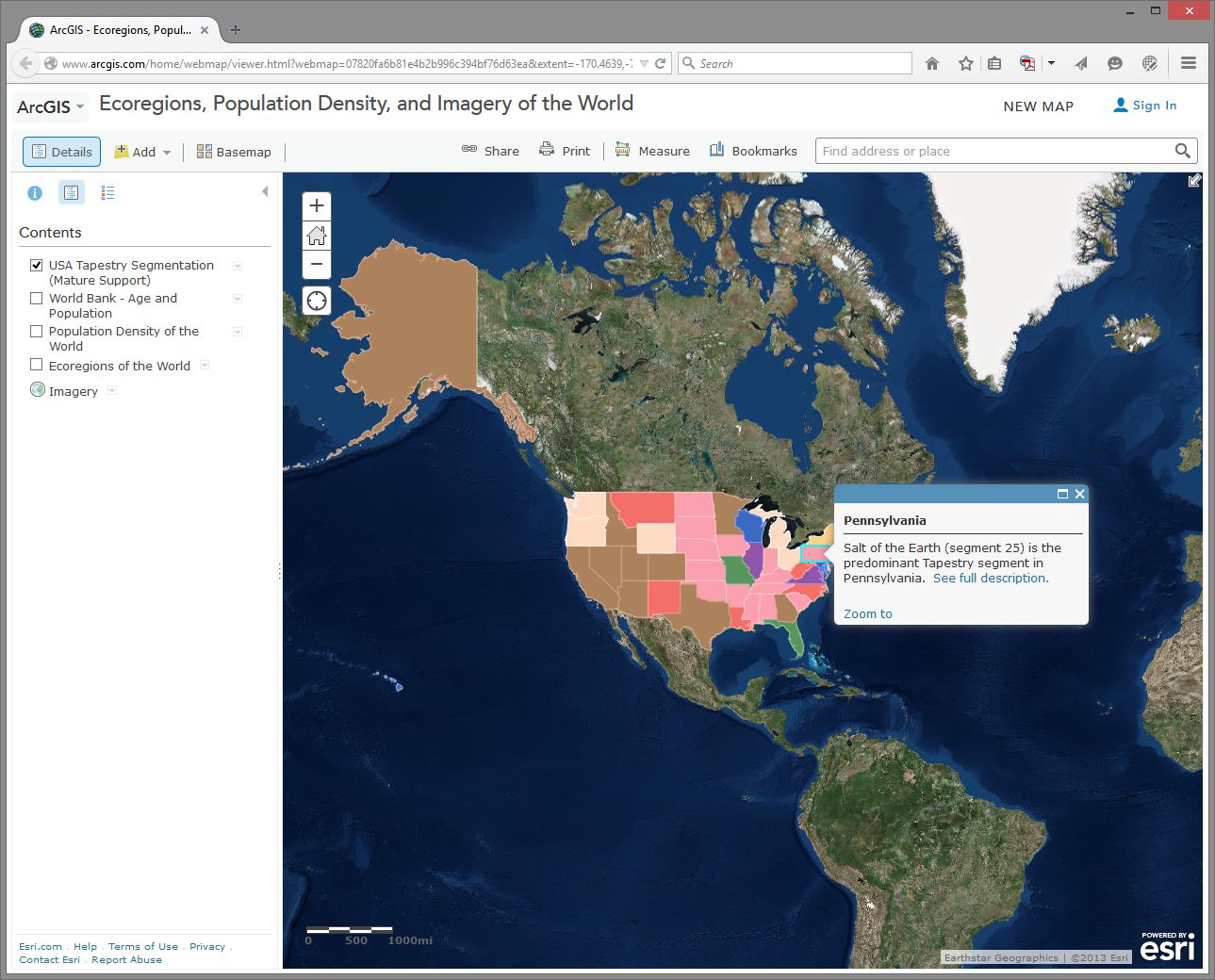

Go to Bookmarks and select the North America bookmark. Turn off all map layers. Then use the Add button and search for the data layer called Tapestry in ArcGIS Online. The “Tapestry segment” is one of these lifestyle variables we have been discussing. Add the USA Tapestry Segmentation (Mature Support) layer to your map (it should be the first result in your search results list). Zoom in and out a couple levels and watch what happens to your map (you should see counties turn into states as you zoom out to show the entire world).

Click on the state you live in (or, if you live outside the USA, pick one that sounds cool). What is the predominant tapestry segment for your state? In the popup box that appears, select See full description to learn more about how that segment is defined. Your map should look something like this:

- What is the tapestry segment of your neighborhood or a neighborhood you are interested in?

- Would you say that the tapestry segment describes you accurately? Does it describe some of your neighbors? Does the segment description make you laugh, or laugh nervously?

- What influence does the map scale have on the data you are analyzing?

Now change the Basemap in the neighborhood you are examining to Imagery and then make the Tapestry layer semi-transparent.

Is there anything on the imagery that gives a clue as to the neighborhood’s lifestyle? What do the structures and streets tell you about this place?

If you have time, feel free to explore additional data layers inside ArcGIS Online. We’ll be using it throughout this course, so if you can become more familiar with it now, it will serve you well later. Add other population data of interest to you, such as median income, median age, and median home value. Do these variables help explain the tapestry segment of your chosen neighborhood and surrounding ones?

Congratulations – You Just Made Some Maps!

Awesome job. You have just been using maps in exciting ways to explore the relationships between the environment and people and to examine components of the population, using a web mapping system. Along the way, you have considered scale, data, the map projection, and other geographic concerns.

Credit Where It's Due

This lab was developed by Joseph Kerski [54] and Anthony Robinson [55].

Discussion Prompts

Privacy and the Geospatial Revolution

Have a look at a map that was created by students who took this class in 2015. [56] This map shows student's self-reported locations and some basic demographic information. It's incredibly interesting and helpful for me as the instructor, because now I have a better sense of all of the amazing places where people were experiencing this course. Some shared what seem to be very specific locations (down to a specific house, for example). Others shared locations that seem to be much more generic. People have always had conceptions of private and public space, but geospatial privacy is more relevant than ever due to the proliferation of ways in which your personal location can be shared.

Here are some prompts you can use to discuss what you've learned in this lesson:

- Why did you feel comfortable sharing what you shared?

- What is scary about potentially losing control over your geospatial privacy?

- What are some positive things that could come from openly sharing your personal location with others?

- What about geospatial privacy has really changed over time? 200 years ago, would it have been possible to live in your current location without your friends and family knowing where you were most of the time?

- Have a look around at what people submitted for answers to the question “How do you use maps?” Are there spatial patterns associated with certain types of answers?

Lesson 2: Spatial is Special

Lesson 2, Lecture 1

Spatial is Special

Leading off with a cliché is always dangerous, but I do really believe that Geography as the science of place and space depends in part on the axiom that what is Spatial is Special. This Lesson focuses on spatial thinking and spatial relationships that underpin everything we try do to with mapping and geographical analysis. A lot of this stuff will seem like common sense when you see the examples, and other aspects are likely to represent a new way of thinking about the world.

Most sciences have associated laws and axioms that govern fundamental principles and methodological approaches. In Geography we really just have one: Tobler’s First Law of Geography. In 1970, in a paper describing an urban growth model for the city of Detroit [57], Waldo Tobler proposed “the first law of geography: that everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things.”

If this law makes you say, “Well, yeah, duh!” – Great. That’s how I felt when I first encountered it too. Of course that’s true, as it makes perfect sense when you think about any possible example. I’m more likely to interact with people in my neighborhood in Central Pennsylvania than I am to interact with folks in Kolkata. The law of course extends well beyond stuff related to humans – you can expect animals, plants, and people sending too much email to each other to generally follow this law as well. Note that Tobler is talking about relationships between things. Near things are more related, but that doesn’t mean they’re necessarily more similar. The measure of similarity of observations that are close to one another is called spatial autocorrelation. While it’s not necessarily true that stuff nearby is in fact similar, there are often aspects of similarity that can be observed and measured (e.g. there are a lot of people at Dulles Airport who wear those annoying Bluetooth headset things, and they often buy very large Soy Lattes at Starbucks).

Plenty of studies have attempted to formally evaluate Tobler’s Law, and there remains consensus that it is a fundamental principle of Geography. It turns out that it even extends to something like Wikipedia if you explore the spatial relationships that underpin thousands of its articles [58].

So I think it’s quite clear that Spatial is Special, and it’s what helps separate Geographic analysis from all other forms of investigation. We aim to take location into account and leverage what we know about spatial relationships to answer questions.

However, I’d be remiss if I didn’t point out that Geographers are a really self-conscious lot (we cry if someone shouts), and there’s been considerable debate on whether or not Spatial is Special (maybe if we exclude the IT part? [59]), and whether or not Tobler’s Law is really a law [60] after all or if it matters. I’m pointing out these debates here to acknowledge that my perspective, while it’s certainly the most common one in Geography, isn’t the only valid point of view. Academics love some navel gazing, that's for sure.

Thinking like a Geographer

(by thinking Aspatially)

Chances are that you already think like a Geographer all the time, you just don’t know it yet. You compare places to one another based on their distance and their similarity across a range of attributes. You talk with your friends about Red States and Blue States [61] whenever there’s a Presidential election. You decide where to buy a house based on how long it takes for you to drive to the nearest delicious breakfast food [62] and based on which school district it’s in.

But I want you to go a couple steps deeper here, and a good way to do that is to first try to ignore space and place entirely while exploring a problem. Consider the following dataset:

| # of Annoying People | Total Population | Average Age | Average Income | # of SUVs | County | State |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 72 | 998 | 26 | 48000 | 72 | Hatchback | Wholefood |

| 48 | 2000 | 65 | 32000 | 48 | Dialupia | Wholefood |

| 776 | 2250 | 44 | 72000 | 750 | Sriracha | Traderjo |

| 789 | 3500 | 36 | 12000 | 700 | Muffintown | Wholefood |

| 469 | 1200 | 31 | 22500 | 461 | Fixieplaid | Traderjo |

| 525 | 1400 | 43 | 66000 | 400 | Burb-on-Burb | Wholefood |

| 62 | 65 | 33 | 92000/td> | 59 | Bluetooth Village | Wholefood |

| 2300 | 16450 | 51 | 35000 | 1950 | Pabsto | Traderjo |

| 9654 | 52510 | 44 | 49000 | 8912 | University Collegeville | Traderjo |

| 779 | 1459 | 41 | 61000 | 398 | Kingo | Traderjo |

What are some things we could do to analyze this information *without* considering anything spatial? For starters, we could count how many annoying people exist (14,695). The overall rate of annoying people as compared to all people can be calculated (~18% of all people in this dataset are annoying). We could determine the average age of this sample dataset (~45 years old). You get the idea.

I’ll bet almost anything (a bag of the best Gummi bears ever [63]) that you’re finding it hard to ignore the spatial stuff that’s inherent in this data. You want to see these counties and states, compare them to one another, identify the possible urban areas and rural locales, explore possible cultural differences, etc… If so, then congratulations, you’re a spatial thinker! If not, then allow me to demonstrate further.

This is a map of the fake states and counties from Table 2.1. The top row of counties is Muffintown, Bluetooth Village, and Dialupia. Below that is Hatchback and Burb-on-Burb. These 5 counties make up the state of Wholefood. Below Wholefood is the 5 counties of Traderjo. The first row of Traderjo is Kingo, University Collegeville, and Pabsto. Below that is Sriracha and Fixieplaid.

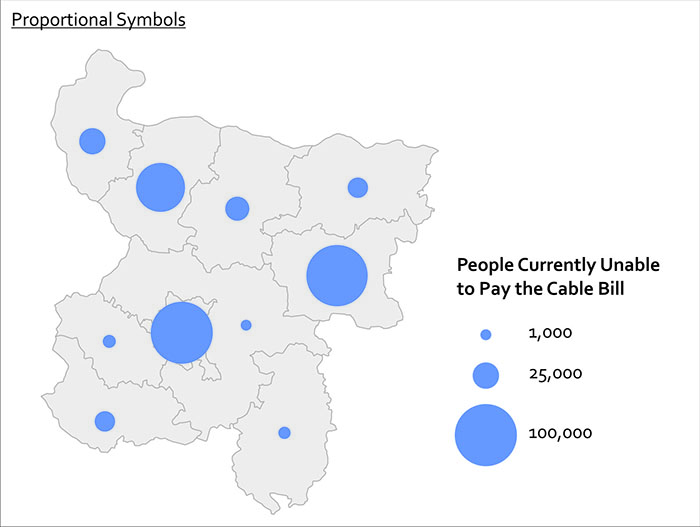

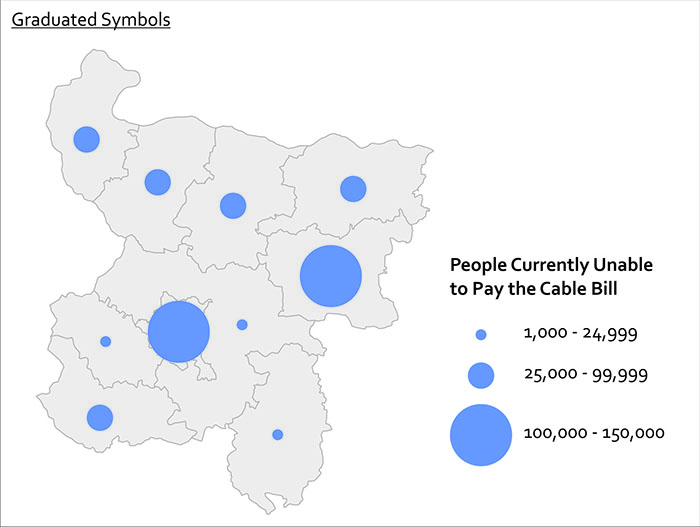

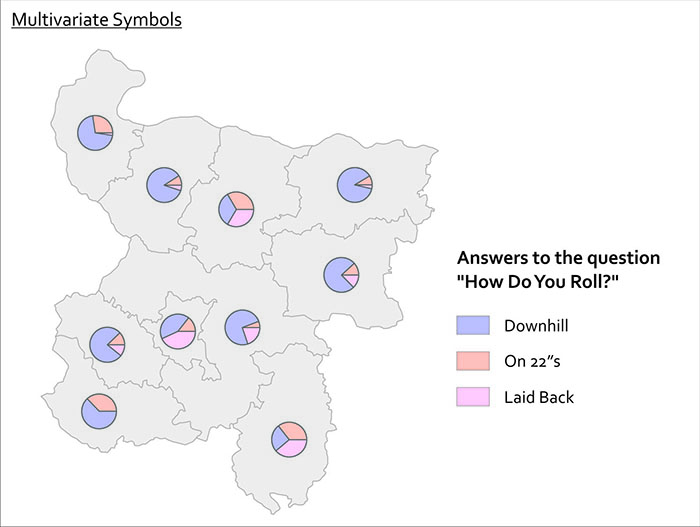

Here’s the basic Geography of my fake states and counties.* Now you are able to compare the relative distances between places, right? Let’s overlay some additional information here to give you more context. I’ve made a little population map using graduated circles (each circle size represents a given range, so the smallest circle size here would include everything from 0-1000). Next to it I’ve made a choropleth map (not chloropleth – there’s no chlorine in this map). Choropleth is a fancy way of saying “colored areas.”

This map estimates the populations of each county. It shows that Bluetooth Village and Hatchback have the 2 smallest populations, at between 0 to 1000 people. Muffintown, Dialupia, Burb-on-Burb, Kingo, Fixieplaid, and Sriracha all have populations between 1000 to 3000. Pabsto has a population between 3000 and 10000. University Collegeville has a population between 10000 and 50000.

This map estimates the percentage of each county's population that owns SUVs. In Muffintown, Dialupia, Hatchback, University Collegeville, and Pabsto 0 to 25% own SUVs. In Burb-on-Burb, Fixieplaid, and Sriracha 26 to 50% of people own SUVs. In Kingo 51 to 75% of people own SUVs. In Bluetooth Village, 76 to 100% of people own SUVs.

Now that you’ve seen both of these maps, what can you start to say about possible spatial patterns? What other maps would you want to see in order to answer questions about this data? For instance – I’d want to know the location of major roads and businesses. I’d want to see how the population relates to those features. I’d want additional data showing the # of fancy coffee places in each county so I could compare SUVs to Coffee and see if I could develop a community profile much like the ones you explored in Lab 1 [64].

I’m sure you’re thinking spatially now. If you still think this is crazy talk then maybe we’re just not meant for each other after all. :(

*Want to know why I’m using hexagons? Check out Central Place Theory [65].

Lesson 2, Lecture 2

Spatial Relationships

To have a science of place and space, and to investigate whether or not Spatial is Special, you need to set some ground rules for what is possible when it comes to spatial relationships. Spatial Topology is the set of relationships that spatial features (points, lines, or polygons) can have with one another. To make this pretty dry topic a lot more interesting, let’s consider spatial relationships using our personal relationships as a metaphor.

Some common spatial topological relations include:

Equals – A is the same as B

When we first met each other, we felt like we were “one.”

Touches – A touches B

Our first kiss was gentle – no tongue.

Overlaps - A and B have multiple points in common

During our honeymoon we… <deleted>

Contains – A contains B

For 9 months the baby was inside (and much quieter).

Disjoint – A shares nothing with B

Later on, we got sick of each other and watched TV from opposite sides of the room.

Covers – A covers B (or vice versa)

The dog sleeps on top of me, creating a huge amount of heat.

Crosses – A and B have at least one point in common

Although we both know how to find our way home from the grocery store, the only routing point we have in common is our driveway.

This list isn’t exhaustive, but it’s a good starting point. If you really get excited about this stuff (congratulations on being single!) then there is a ton of literature out there to review. I recommend starting with this paper [66] and spiraling out from there.

This stuff may seem a bit dry, but it’s really important because it formalizes the ways in which we can expect things to interact in space. Moreover, knowing all of the possible spatial relations allows us to create great software tools that can take these relationships into account.

Consider what would happen if we didn’t take these relationships into account. Let’s say you have 500 road segments that you’ve digitized to show your neighborhood’s streets. In order to ask a GIS to identify a driving route from one house to another, all of those road segments have to “know” how they are related to one another. So if your street intersects with the next street, we have to specify how both routes are topologically connected. This is how Mapquest or Google understands that when you leave a highway and go on an offramp that there are certain possibilities for navigation (the offramp is a one-way route and connects to a cross-street), and other things you can’t do (the offramp only allows right-hand turns at the end where it intersects with the cross-street). If you didn’t have a theory behind how things can relate, and ways to specify those spatial relations, you’d just have a zillion streets with their basic locations on Earth, but no way to actually use that information for routing.

Almost all of us have experienced the frustrating case where automagical navigation devices and websites have bad or missing topological information. We exit the highway believing we can make a left turn, but it turns out to be a one-way street and we can only go right. Much cursing ensues. Depending on how well we handle this problem, our topological relationship with our significant other may change drastically that night once we finally make it to the hotel.

Scale and Time

Scale

There are two concepts of scale that are fundamental to Geography. Let’s talk first about scale as it pertains to maps. Map scale is the ratio of the distance on the map to the corresponding real distance on Earth. You’ll often see a bar drawn on a map that says 1 inch equals 10 miles, or something to that effect. This means that one inch of distance measured on the map can be considered equivalent to 10 miles of actual distance on the Earth. It’s common to see these equivalencies written in fractional form instead of plain English, e.g. 1:100 or 1/24000. These are called representative fractions.

You learned a bit in Lesson 1 [67] about why it’s impossible to make perfect translations from the 3D Earth to 2D maps. This has an important impact on map scale. Depending on what map projection you’re using, your map scale will vary across your 2D map. This is another reason why map projections are important. Imagine if I gave you a paper map for a kayaking trip and I designed it using a projection that looked really cool but had scale varying wildly across the map (1 inch in the middle = 1 mile, 1 inch at the top = 50 miles). You might plan out your entire trip without realizing that you’re comparing completely different distances. That would be very mean of me to do, especially if there are lots of mosquitoes and you only brought one bag of beef jerky. At large scales (i.e. “zoomed in”), if you use a conformal projection [68], the differences in scale measurements are small enough to be insignificant for most users.

The second major concept of scale is a more general one. With Geography you have the power to explore and analyze phenomena at different levels of granularity. You could look at really large-scale (1:100) patterns in a neighborhood, or you could look at really small-scale (1:10,000,000) patterns across multiple countries. You did that last week in the lab assignment when you looked at Tapestry data at state, county, and finally neighborhood levels. At each scale the story you could tell totally changed, didn’t it? This kind of scale is often called the scale of analysis by Geographers, as opposed to the specific map scale that refers to how reality is directly translated by a map.

What About Time?

Geography requires space and spatial relationships in order to exist, but it also requires attention to time. Practically all geographic problems take place through some sort of dynamic process – meaning that things are changing from Day 1 to Day 100, for example. If you think about how most maps are made, this presents a problem, doesn’t it? How do you show changes over time? What if you don’t have data for every time step?

It’s outside the scope of this course to delve very deeply into this topic, but I want you to be aware of a couple of key examples so that you can understand the impact that time has on every map you read (and every map that you make).

I am still amazed that we can now poke around tons and tons of high-resolution satellite imagery to look at the Earth from above. Back in the old days when we had to yodel over the phone [69] to connect to the internet, this kind of thing was a total pipe dream. Anyway, let’s do a little exploring right now to have a peek at how time is inextricably linked to Geography.

In the first example here, I’m playing around on Bing Maps [70] to look at satellite imagery of Salzburg. My Grandmother was born in Salzburg, met my Grandfather there after the war, and a lot of my extended family lives there today. A summer afternoon on the rooftop at the Hotel Stein [71] is an unforgettable experience if you ever have the opportunity. But I digress. Check out what’s happening on the west side of the city; see how it looks like two pictures have been abruptly slammed together?

Furthermore, they’re of considerably different quality as well. The stuff on the west is blurry compared to the stuff on the east. So there’s a quality problem that’s immediately apparent, but there’s a bigger issue that you should always pay attention to – look at the lower right corner on any mapping service like this and you’ll see a copyright notice identifying who took the images and when they were copyrighted. In this case, there are two different sources cited from different times (2012 by Nokia and 2013 by Microsoft).

The images were taken at different times and from different sensors. This could be a good thing if you had complete coverage from both times and you wanted to look at changes happening to Salzburg, right? But it’s often the case that Geographers have exactly this sort of scenario where you have part of your data from one time and part from another, without any overlap at all. We don’t know when exactly in each year, but they could be taken during completely different seasons (which would explain some of the color differences), not to mention during different years.

The bottom line here is that time is an important factor to consider, and it’s rare to have perfect information covering every place you want to explore for every relevant time period. It doesn’t mean that you can’t make a useful map. Remember when you worked with demographic data in the Lesson 1 Mapping Assignment [72]? All of that data was based on snapshots at particular times, and frequently you were mixing together measurements taken at one time with measurements taken at another. The Geospatial Revolution has brought us closer, but we’re still a really long way away from having real-time Geographic information about everything at every second.

Video Activity

This Lesson's video assignment is to watch Chapter Two, from Episode Two of the WPSU Geospatial Revolution series [73]. This video highlights how businesses are using geospatial technologies to support better customer service and efficient operations.

Mapping Assignment

Changing Landscapes, Sharing Maps, and Fun With Projections

In this lesson you reflected on spatial relationships across space and time. This lab gives you the opportunity to practice these concepts using GIS tools. GIS was originally created way back in the 1960s to analyze these kinds of relationships. Sure, you could analyze spatial relationships via paper maps or plastic transparencies, but that’s clunky (ever tried to fold a paper map back into its original shape?). And what if you want to change the variables, or the way the data is classified, or the map scale? A GIS gives you the flexibility and power to analyze lots of data efficiently.

Ch-Ch-Ch-Changesm(sorry)

One type of change that is evident all around us is physical change and demographic change in our own communities. Think about your own community:

- What has changed since you moved there? What forces are causing that change? How did your community look in terms of the people who live there and the uses of the land in your community 10 or 100 years ago?

- How will your community look in 10 or 100 years? Could any of these changes be mapped? How do these changes compare in magnitude and scale from those changes in other parts of the world?

Unless you have been living under a rock since the 1950s, you know about space probes that have been launched to observe the Moon, Mars, and other objects in our own solar system and beyond. Since the early 1970s, satellites have also been launched specifically to observe the Earth. Some observe oceans, while others observe agricultural health, atmospheric composition, weather, or other phenomena. The first of these was Landsat [74], short for “land satellite.” Landsat became a series of satellites operated by NASA and the US Geological Survey since 1972. Landsat observes the Earth in the visible and infrared portions of the spectrum. In an infrared image, healthy vegetation appears red, cities appear gray, water appears black, and other interesting colors appear as well. The point is not actually to create weird colors, but that the infrared imagery allows for changes to be detected easily on the landscape, such as urban sprawl, agriculture, deforestation, and fluctuations in water elevation.

Open a web browser and access the Esri Change Matters site [75].

Change Matters uses Landsat imagery and ArcGIS Online. You should see three side-by-side web GIS maps, similar to the image below.

The first set of scenes is that of Mount St. Helens from 1975 and 2000. Use the information provided in the link at the lower right "how to interpret a change image" if you need it, to answer the following questions:

- Describe a few changes you observe in Mount St. Helens from 1975 to 2000.

- What do you think is the reason for those changes? Google about St. Helens if you need to.

Using the search box above the images, enter "Aral Sea."

- Describe the changes in the Aral Sea.

- What do you think are the reasons for those changes? Do some more research if you need to.

Now, examine other places around the world using this resource. What does your hometown look like?

Zoom in on one of the Change Matters image sets. The spatial resolution of Landsat imagery is now 30 meters x 30 meters (it was coarser in its earliest iterations). So, while you can’t peep on people sunbathing at this resolution, you can detect large changes across the Earth’s surface.

To share a map from the Change Matters site: click on the green box icon at the top right of the interface. That will give you a URL you can share, and those Twitter/Facebook buttons work nicely too.

Scale Matters

Now, head over to ArcGIS Online [76].

You are looking at the Northeastern Junior College campus in Sterling, Colorado. Click the Content button at the upper left of the interface to see the map layers that you have at your disposal. You should have Map Notes, USA Topo Maps, and Imagery with Labels.

Click on the pushpin at the intersection of the paths that form an “X” on campus. In the popup box that appears, you should see some notes and a photograph taken on the ground. In a few minutes you’ll create your own map notes and popups. Click on the photograph. You should be directed to a new website.

- What website was the photograph linked to?

Unlike the Landsat images, this satellite image was taken in the visible spectrum. It comes from a satellite operated by DigitalGlobe [77], and it has a much finer resolution than the Landsat imagery. You could definitely use this stuff to count the number of dog turds in someone’s lawn.

- What is the smallest object that you can see on this satellite image?

Now go to Bookmarks and select Sterling. You should now be looking at the town of Sterling, Colorado, with the USA Topo Maps layer as semi-transparent. Earlier, you used a side-by-side set of images to detect change over time. Here, using transparency on layers is another way you can look at change over time. Click the small arrow next to USA Topo Maps in the list of layers and adjust the visibility of that layer by clicking on Transparency and then drag the slider around. The USA Topo maps layer is a USGS [78] topographic map; and in the case of Sterling, the map was created in 1971. Your MOOC instructor was -9 years old at the time.

- Describe two changes you can detect in the town of Sterling from 1971 to 2011.

Now examine the Northeastern Junior College Campus, comparing the current campus as seen in the satellite image to the features on the 1971 topographic map by sliding the transparency control back and forth for the USA Topo Maps layer.

- What feature occupied most of the campus back in 1971?

Until now in our lab assignments you have been using maps and layers created by others. One of the revolutionary things about today’s mapping methods is that you can create your own content, save it, and share it with others quite easily. Let’s start doing that now. To do so, click on Sign In in the upper right hand corner of the map that you are examining.

Your screen should look similar to the one shown below. If it doesn't, navigate to the ARCGIS home page [79] directly.

At the lower left, click the link to Create a Public Account. Follow the steps there to create your account. Where it asks you to name the Organization you're part of, you can just say "Coursera" there. You will also need to give Esri a phone number, but you don't have to give them a real one. Just plug in 999 instead. You also need to review and accept the terms of use before you can click Create My Account. Once you have created your account, you should be automatically logged in. It should drop you at a page where you can edit your profile details if you'd like.

None of this will cost you any money, result in 40 catalogs sent to your house or anything crazy like that – it’s just a way for you to be able to upload stuff, save your maps, and share things more easily.

Now that you are signed into ArcGIS Online, you can do everything that you have been doing last week and earlier in this current lab exercise, but now you can save your maps. You can build on them as you see fit. And because these maps live online, you can share them with colleagues; you can embed them into your own web pages, you can create web applications from them, and you can reduce your cholesterol by 30% while improving your ability to sing opera. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves: let’s begin with those pushpins, popups, and embedded images and links that you were examining earlier by creating your own. On the menu bar at the top of the page, click Map to continue.

Navigate now to a different location in the United States that is of interest to you. If your map still is titled “Northeast Junior College” then click on “New Map” to start creating a completely new map. I would navigate to Princeville, Hawaii because it’s freaking [80] awesome [81]. Add the USA Topo Maps layer from ArcGIS Online (uncheck the "within map area" option) and compare the Imagery layer from the Basemap to the USA Topo Maps layer for your chosen location. Zoom to a location where you can observe change on the landscape between the topographic map and the satellite image.