Lessons

Lesson 1: Materials Classification

Overview

In today’s society, virtually every segment of our everyday life is influenced by the limitations, availability, and economic considerations of the materials used. In this lesson you will be introduced to the interconnectivity of processing, structure, properties, and performance of the design, production, and utilization of materials; the role of materials scientists and engineers; and the three important criteria in materials selection. You will also be introduced to the classical classification of materials: metals, ceramics, and polymers, as well as, composites and the advanced materials classification used in modern high-tech applications.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Describe, with specific examples, the role of materials in human development during the Stone Age.

- List the six different property classifications of materials that determine their applicability.

- Cite the four components that are involved in the design, production, and utilization of materials, and briefly describe the interrelationships between these components.

- Describe the way in which scientists and engineers differ in their utilization of materials.

- Cite three criteria that are important in the materials selection process.

- List the three primary classifications of solid materials, and then cite the distinctive features of each.

- Briefly define smart material/system.

- Note the four types of advanced materials and, for each, its distinctive feature(s).

- Judge which material is most likely to be a promising candidate for utilization when given the primary or advanced material classifications of a list of candidate materials and one design selection criteria.

Lesson Roadmap

Lesson 1 will take us 1 week to complete. Please refer to Canvas for specific due dates.

| To Read |

Read pp 7-24 (Ch. 1) in Introduction to Materials ebook Reading on course website for Lesson 1 |

|---|---|

| To Watch | Secrets of the Terracotta Warriors |

| To Do | Lesson 1 Quiz |

Questions?

If you have general questions about the course content or structure, please post them to the General Questions and Discussion forum in Canvas. If your question is of a more personal nature, feel free to send a message to all faculty and TAs through Canvas email. We will check daily to respond.

Why Study Materials?

When materials scientist and narrator of The Secret Life of Materials videos (used in this course), Mark Miodownik, opens up the video on metal, he is at Piccadilly Circus in London, England. He marvels at how strange but wonderful it is that everything around him is man-made. This is not unique to London. A visit to the center of New York, Tokyo, Hong Kong, Beijing, Dubai, Paris, or any other 21st-century modern city would yield a similar situation. It might seem like a cliché but we are surrounded by materials. And with the range of materials available - whether it be in our professional or personal lives - we are constantly being asked to make choices about materials.

Something as routine and everyday as purchasing carbonated beverages is an example where materials choice could come into play. As we will see in the textbook, carbonated beverages can be purchased in glass, metal, or plastic containers. What factors drive manufacturers of carbonated beverages to offer their products in a range of different materials? What are the advantages and disadvantages when comparing the different materials choices for carbonated beverage containers? When selecting a material for a product there are many factors that must be taken into account, including properties, performance, and lifetime of the material; availability of raw materials; costs and energy usage in all steps of the processing; sustainability; waste disposal, etc.

Why is it important for you to understand materials? Products, devices, and components that you purchase and use are all made of materials. To select appropriate materials, and processing techniques for specific applications, you must have knowledge of the material properties and understand how the structure affects the material properties.

Throughout history, material advancement has gone hand-in-hand with societal advancements. The Stone Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age were all significant materials and societal periods in humankind's development. One question I would pose to you: what is today's materials age? Is it the polymer age? Or perhaps we have already advanced past that one. Are we in the age of silicon, i.e., the electronic materials age? Or, are we possibly moving into a nanomaterials age? A biomaterials age? Some might suggest that we moved into the information age or the digital age. In any of these cases, it is clear that the materials and the capability of the materials underlying these technologies are integral to the current and future capabilities in these areas.

Now let us explore how deep-seated materials are in our culture by looking back at materials in antiquity.

Materials in Antiquity

Three of the greatest ‘cultural’ revolutions occurred in antiquity, and they are named for the material use associated with these revolutions. They were predominantly bloodless, occurred over a millennium, and were revolutionary, not evolutionary. These three revolutions occurred during the Neolithic Age (part of the Stone Age), the Urban Age (Bronze Age), and the Iron Age.

Before we look at the Neolithic Age revolution, let’s take a look at the pre-Neolithic Age. If we look at the human timeline below we can see that the usage of stone tools began about 3.4 million years ago. This marks the beginning of the Stone Age, which lasted until the advent of metalworking and ended at different regions from ~9000 BCE to 2000 BCE. The genus Homo emerged during the Stone Age. The earliest usage of cooking, clothes, and fire occurred during this pre-Neolithic Age, with their earliest known dates shown in the figure below. In addition to cooking, fire was particularly important from a materials point of view. Fire was used for the tempering of wood arrowheads, annealing flint, and creating charcoal before the Neolithic Age, and has been an important component of materials processes throughout all ages of human existence.

The first of these revolutions was the Neolithic Revolution, which was highlighted by the transformation from a hunter/gatherer population to a farmer/skilled artisan population. It has been argued that three steps were required for the Neolithic Revolution: 1) hunter/gatherer population increase, 2) food production in marginal areas, and 3) several communities at similar stages of development. Near the end of the Stone Age, six civilizations emerged that satisfied these requirements.

Now we will take a closer look at the materials used during the Stone Age.

Flint (and Obsidian)

Flint and obsidian were very important Stone Age materials. Commonly found with chalk and limestone, flint is a form of the mineral quartz. Obsidian is a naturally occurring volcanic glass. Both were widely used in weapons and tools. As we will learn in this lesson, flint and obsidian are classic examples of ceramics. Both are hard and can be worked to produce a sharp edge, but both materials are prone to breakage. Slowly heating flint to 150 to 260 °C (300 to 500 °F), holding the temperature there for 24 hours (annealing), and then slowly cooling it back to room temperature, can relieve internal stresses which can improve the ability to produce flint tools or weapons with a sharper cutting edge. As discussed later, since flint is typically found with chalk and limestone, it is possible that the annealing of flint led to the discovery of lime mortar.

Charcoal

Charcoal is perhaps the greatest invention of the Paleolithic (Stone) Age. Charcoal is produced by partially burning organic matter (wood, bone, etc.) while limiting the supply of oxygen. One way of producing charcoal is to pile a large amount of wood, as shown in the figure, and covering it with soil to limit the amount of oxygen feeding the fire. During the burning process, considerable water is released, and at the completion of the burn, the wood is reduced to black brittle lumps of carbon (charcoal).

Charcoal played an important role throughout the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age. Why? Very few elements (noble metals and copper in very limited quantities) occur naturally in their pure form. Elements usually occur bound with other elements forming compounds, and typically occur in a mixture with other compounds. Heat is usually applied to break the compounds or melt the element to produce the raw material needed for manufacturing, such as copper and iron.

The temperatures required depend on the compounds and elements involved and can vary considerably. The temperatures obtainable by fire depend on the fuel used and the supply of air. If wood is used as the fuel in an open fire, temperatures in the fire might range from 350 to 500° C. Charcoal, being a denser and drier fuel source, can provide temperatures up to 800 °C under similar conditions. If the fire is confined, such as in a kiln or a furnace, and air is forced into the fire, it is possible to obtain even higher temperatures. For charcoal, it is possible to reach temperatures above 1000 °C.

Later, in our lesson on metals, we will see that this temperature is insufficient to melt pure iron, which is why the processing of impure iron (iron plus carbon) was developed first. Impure iron has a much lower melting temperature than pure iron. We will see that an advanced design furnace coupled with a hotter burning fuel source (coke, a form of coal) was needed to obtain pure molten iron.

Lime Mortar

When annealing flint, you can expect chalk or limestone to be present. Chalk and limestone are composed primarily of calcium carbonate (CaCO3), which is the same mineral present in hard water. It often shows up as a white residue on plumbing fixtures. If chalk or limestone is heated above 800° C (obtainable with charcoal), the gas carbon dioxide is released from the calcium carbonate leaving lime (CaO). Lime produced in this matter is referred to as quicklime or burnt lime. If water is added, this quicklime or burnt lime hydrates to form a white pasty substance known as slaked lime.

It is quite possible that an observant fire tender or cook could have noticed that, after encountering rain, this material would dry and form a hard substance. We refer to the substance as lime mortar, a type of cement. It is common to confuse the term cement with concrete. Cement is a binder or material that glues things together. Concrete, on the other hand, is a combination of cement and aggregate (sand, stone, etc.). Concrete is one example of a composite material. As we will see in this lesson a composite material is a material that is composed of two or more distinct materials in combination. Cement is the material within concrete that binds the stone and sand together.

In addition to the development of lime mortar in the Fertile Crescent, the Incas, and the Mayans independently discovered lime mortar around 5000 BCE, and it was widely used in ancient Rome and Greece around 4000 BCE.

'Plaster of Paris'

Originally, the term ‘plaster of Paris’ was coined in the 1700s to describe plaster produced from gypsum located outside of Paris. Over time, the term ‘plaster of Paris’ has become the generic term for gypsum-based plaster. Many ancient Egyptian tomb paintings are created on plaster. It is produced in a way that is similar to lime mortar, except gypsum is used in place of lime and much lower temperatures are needed. The resulting plaster is not as hard as lime mortar. Plaster vessels dating from 6000 BCE have been found from ancient Egypt.

Primary Civilizations

As mentioned before, near the end of the Stone Age, six civilizations that emerged that satisfied the requirements considered necessary for the Neolithic Revolution. If you look at the map below, you can see that there were two New World civilizations and four Old World civilizations, along with their names.

The four Old World civilizations had two very important advantages over the two New World civilizations. Namely, they were situated along great river systems and, being more numerous, had a more robust trade system in place. The great river systems were very important components in trade, but possibly of equal or greater importance was the benefit of annual flooding. Annual flooding reinvigorates farmland and, before the advent of modern farming techniques, allowed for the successful growth of crops year after year over multiple decades without the need for artificial fertilizers or crop rotation management schemes.

Two of the Old World civilizations, the Nile Valley and Mesopotamia, formed what has been called the Fertile Crescent, which is widely regarded as the birthplace of civilization. As can be seen in the figure below, both locations possessed great river systems and, due to their proximity, had well-established trade routes. At the close of the pre-Neolithic age, these two civilizations were experiencing increasing populations, had extensive food production capabilities, and had several communities at similar stages of development.

Mudbrick

The mudbrick was developed during the pre-pottery (Aceramic) Neolithic Age. Mudbricks were composed of a mixture that might have included clay, mud, loam, sand, and water mixed with a material to inhibit crumbling such as straw or rice husks. This was another example of a composite material. The ceramic material (clay, mud, loam, sand) by itself could support compressive loads but could be easily pulled apart. The second component of the composite, straw or rice husks, reinforced the first material, making it more difficult to pull the mudbrick apart. Water was used to allow the brick to be easily formed during manufacturing.

Since the early civilizations were located in warm regions with very limited timber, early bricks were sun-dried. The bricks needed to be dried before installation. Otherwise, shrinkage and cracking would occur that would destabilize the building.

Before the usage of bricks, structures were limited to wood and piling of stone. Creation of the brick unleashed creative design of buildings, and the architect was born! Clay or mud (raw material) was readily available everywhere, as was the strengthening material, straw or rice husks.

Later gravel and bitumen were used for stronger bricks. Bitumen is a naturally occurring (thermoplastic) polymer that, when heated, becomes a liquid and, when cooled, becomes solid. It is a black, tar-like substance with a consistency similar to cold molasses. Adding bitumen to bricks makes them both waterproof and much stronger. Bitumen is a mixture of hydrocarbons, which contains anywhere from 50 to thousands of carbon atoms. It is found in nature in rock asphalt, lake asphalt, and near other fossil fuels. In addition to being a structural improvement, bitumen, and crude oil sometimes found near bitumen deposits, provided fuel for brick kilns.

Pottery

The development of pottery in Mesopotamia was important for the storage of food protected from moisture and insects. Pottery takes clay and water which, in the proper proportions, form a mass that can be readily shaped. Once in the desired shape, the piece is dried to remove the water and then fired to improve mechanical stability. Clay was readily available and thus an inexpensive material to use.

Initially, unfired clay was used to line woven baskets. Although these unfired clay baskets were not particularly robust, they did provide much-needed waterproofing. Possibly, one of these early clay-lined woven baskets was discarded at the end of its usefulness. One could suppose that at some point the discarded basket was put into a fire to dispose of it. Later, in the cooled coals, someone could have discovered pottery shards and had the eureka moment where they realized that the firing of clay structures would produce pottery.

The development of pottery occurred in Mesopotamia around 7000 BCE. The invention of the pottery wheel occurred in Mesopotamia sometime between 6000 and 4000 BCE. The earliest ceramic objects (figurines) known have been found in what is now the Czech Republic and have been dated as being created between 29,000 and 25,000 BCE. The earliest pottery has been found in China and dates from around 18,000 BCE. In 10,000 BCE, Japan was using roping or coiling to produce pots. In the videos of this lesson, Secrets of the Terracotta Warriors, you will see that coiling was the method used to produce these warriors.

The Near East, at the end of the Neolithic Age (c.a. 4500 BCE), had mastered fire to produce and/or modify a number of materials. They had flint tools and weapons, buildings of mud brick with plaster finish, pottery, well-established trade routes from Mesopotamia to the Indus Valley, and a robust agrarian economy. Discussions about the Bronze Age and the Iron Age await us when we get to the lessons on metals and metal alloys. But now, let's take a look at what is materials science and engineering.

Materials Science and Engineering

In my experience in this course, students have difficulty understanding the difference between materials scientists and materials engineers. In the reading for this lesson, materials science is defined as investigating relationships between structures and properties of materials, and concern with the design/development of new materials. Materials engineering is defined as the creation of products from existing materials in the development of new materials processing techniques. I would restate the roles of material scientists and materials engineers as:

- Materials scientists study materials and create new materials.

- Materials engineers use materials and create new processes.

Now, these statements of the roles for material scientists and engineers are, of course, oversimplifications. As I think you will see in the following video (5:34) produced by the Penn State Department of Materials Science and Engineering we believe that cutting-edge materials research and development require a thorough understanding of both materials science and engineering.

To Watch

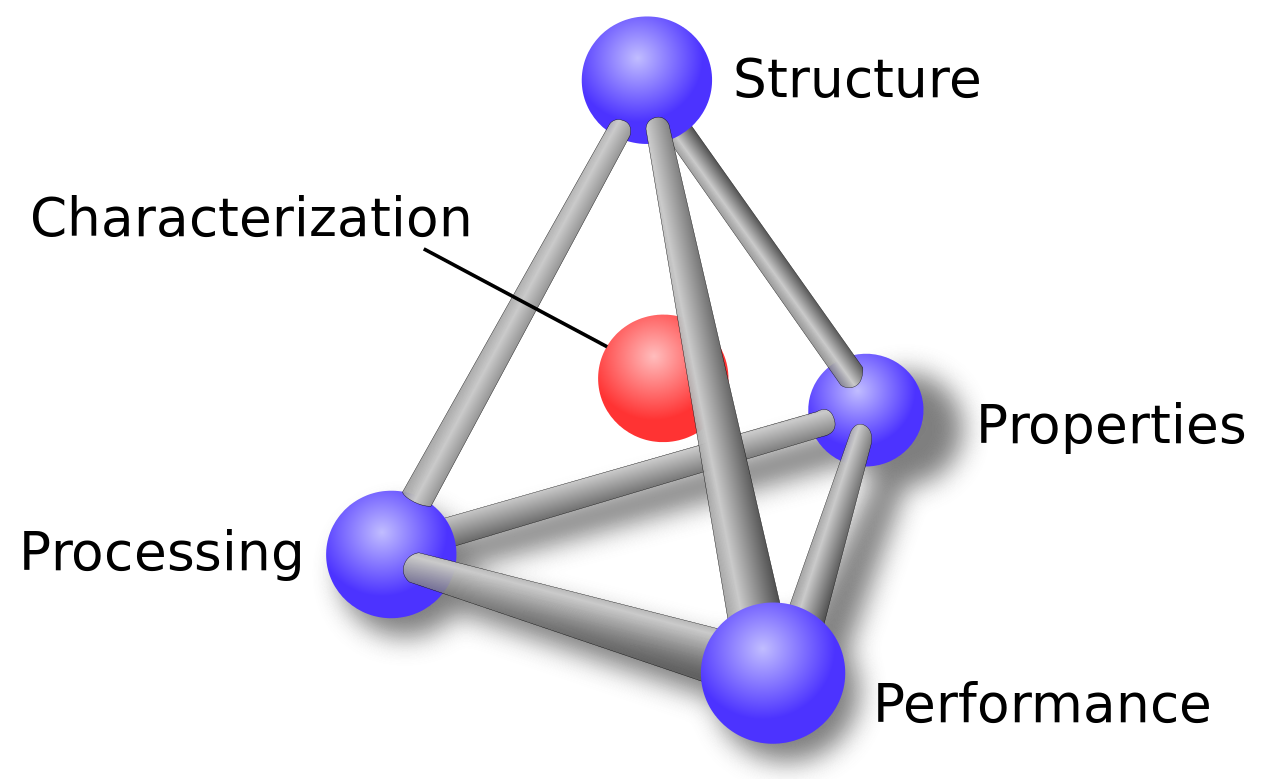

When utilizing a material, one needs to understand that the structure, properties, processing, and performance of the material are interrelated. This is represented by the materials science tetrahedron shown in the figure above. If one alters the processing, there is a direct connection with the structure, properties, and performance of the material. Adjusting any one of the factors will have varying degrees of impact on the other three factors. Characterization is the heart of the tetrahedron, signifying its role in monitoring the four components.

In this course, we will be looking at the four components (structure, properties, processing, and performance) of materials, beginning with properties. Properties of materials can be classified into six categories: mechanical, electrical, thermal, magnetic, optical, and deteriorative. We will start by looking at mechanical properties in lesson four and electrical properties in lesson 12. Unfortunately, we will not have time in this course to look at the other four properties. In lessons 3, 5, 7, and 8 we will look at the structure, both atomic and microstructure. Lesson 10 will be concerned with the processing of materials, and the performance of material will be addressed throughout the course.

Classification of Materials

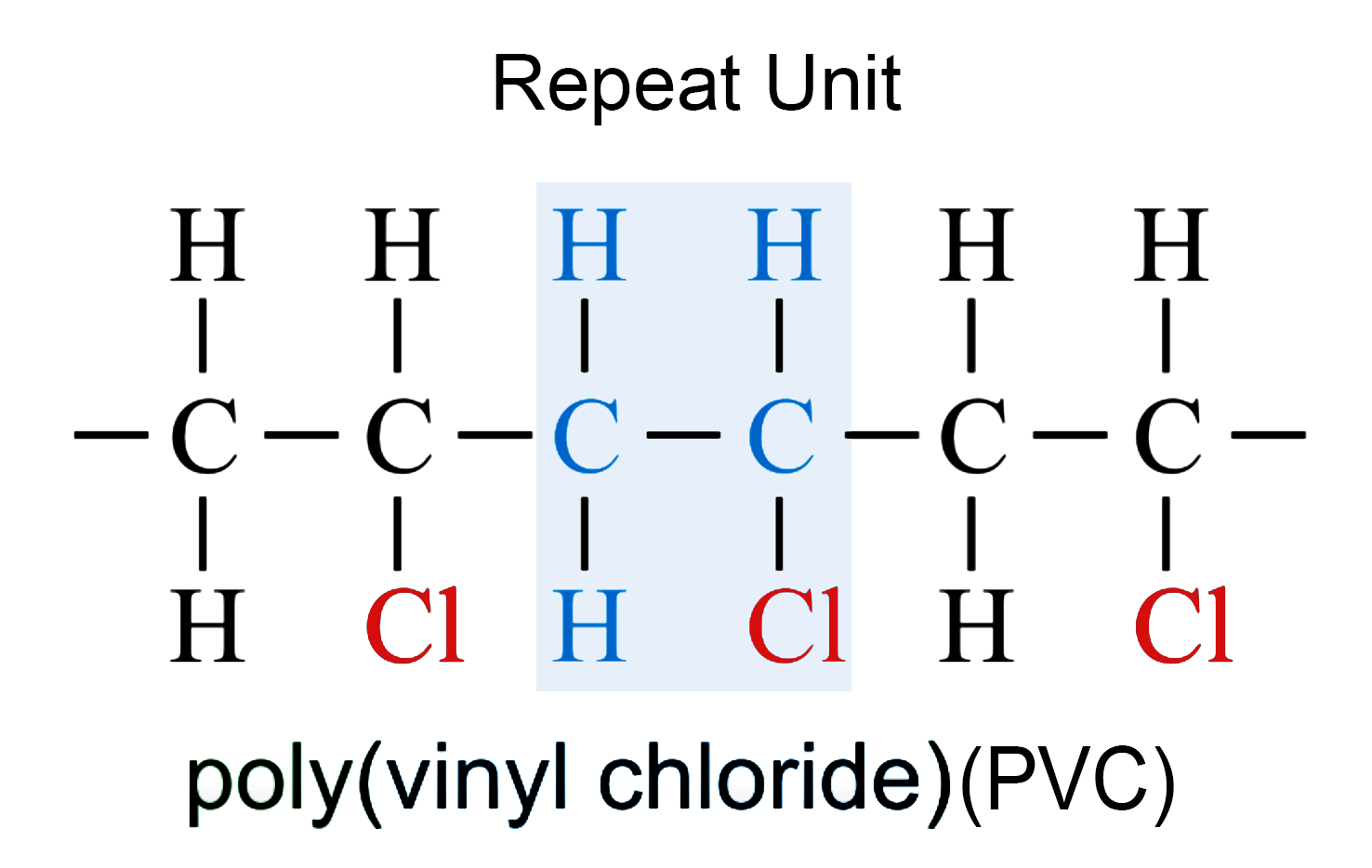

Matter is composed of solid, liquid, gas, and plasma. In this course, we are going to be looking at solids which we will break down into three classical sub-classifications: metals, ceramics, and polymers.

In the reading for this lesson, representative characteristics of the three sub-classifications will be presented. In lesson three the chemical makeup and atomic structure will be further explored. The microstructure of the three classifications will be explored in their lessons.

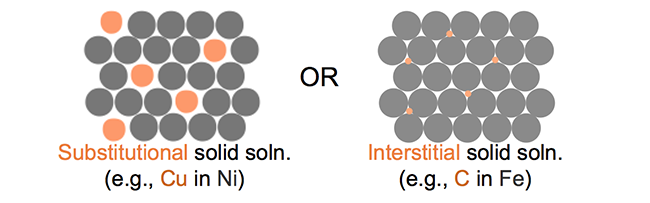

Composites is a special additional classical sub-classification. Composites are composed of two (or more) distinct materials (metals, ceramics, and polymers) to achieve a combination of properties. Composites are introduced in this lesson in the reading and we will have a later lesson devoted to them as well. (Note: composites should not be confused with alloys. We will learn later that alloys are a mixing of a metal with other elements. In an alloy the elements are blended, they are no longer distinct components.)

Advanced materials are materials that are utilized in high-tech applications. These materials are typically enhanced or designed to be high-performance materials - many times with very specific tasks in mind.

Semiconductors are materials that can be made to switch from an insulator (off) to a conductor (on) by the application of voltage. The flow of electrons in semiconductors is somewhere between insulators, i.e., those that do not readily conduct electricity; and conductors, those materials which freely allow the flow of electrons. These materials have enabled our digital electronic age. The development of semiconductors for integrated circuits has allowed for the electronics and computer revolution that we have experienced in the last 50 years.

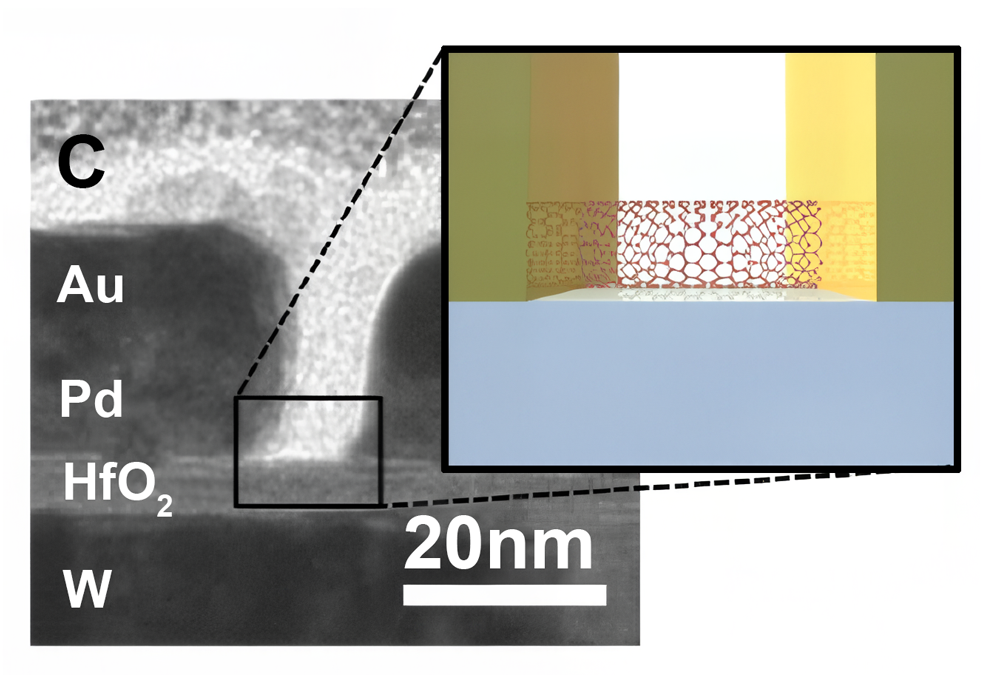

Nanomaterial, whose sizes typically range from 1 to 100 nanometers, are materials in which size and/or geometry can play a significant role in the dominant materials properties. In this size range, quantum mechanical effects can dominate, as well as, chemistry due to a large number of the atoms being surface atoms instead of atoms in bulk. In addition to size effects, these materials sometimes exhibit unique functionality due to their geometry. For example, gold nanoparticles can be very chemically active, unlike bulk gold. This effect is due to a large number of unsatisfied bonds on the surface of the gold nanoparticle.

Biomaterials are materials implanted into the body. In addition to performing their design function, they also have to have the ability to survive in the body (be biocompatible). The body can be a 'hostile' environment for materials. The body might attack the biomaterial as a foreign body (immune response) and the environment (wet and chemically active) in the body is typically one that leads to corrosion.

Smart materials are materials that are designed to mimic biological behavior. They are materials that, like biological systems, ‘respond to stimuli.' When determining whether a material system is utilizing a smart material, it is usually useful to identify the stimuli and the response that the material will exhibit, as well as, what biological system it is mimicking.

The readings and videos in the last two lessons of this course will explore advanced materials in more detail. Now that I have set the stage it is time for you to begin the additional reading for this lesson.

Reading Assignment

Things to consider...

When you read this chapter, use the following questions to guide your reading and always remember to keep the learning objectives listed on the overview page in mind.

- What are the materials' properties that determine materials applicability?

- What are the differences between material science scientists and engineers?

- What are the differences between metals, ceramics, and polymers?

- Does ‘best of both worlds’ apply to composites?

- Which of the materials classifications (metal, ceramics, polymers, composites, semiconductors, smart materials, biomaterials, and nanomaterials) are a distinct class of materials versus a group of materials with defining function composed of materials from distinct classes of materials?

Reading Assignment

Read pp 7-24 (Ch. 1) in Introduction to Materials ebook

Video Assignment: Secrets of the Terracotta Warriors

Now that you have read the text and thought about the questions I posed, take some time to watch this 54-minute video about determining how 8,000 terracotta warriors were manufactured in later third century BCE in China. As you watch this video, please note some of the problems that needed to be overcome and the assembly line approach that was necessary to complete everything in a two-year period.

Video Assignment

Go to Lesson 1 in Canvas and watch the Secrets of the Terracotta Warriors Video. You will be quizzed on the content of this video.

Summary and Final Tasks

Summary

Anthropologists, archeologists, and historians use the level of materials development (Stone Age, Bronze, Iron Age) to designate the stages of societal development. In today’s society, materials and materials development continue to shape development and advancement. In this lesson you were introduced to the important overarching themes of this course:

- materials scientists investigate the relationships that exist between the structures and properties of materials

- materials engineers design the structure of a material to produce a predetermined set of properties

- structure and properties are interlinked

- processing, structure, properties, and performance are interconnected

- environment, wear, and economics are three important criteria for materials selection

- classical classification of materials (metals, ceramics, and polymers, as well as, composites)

- and the advanced materials classification used in modern high-tech applications.

We will utilize the important concepts introduced in this lesson throughout the rest of the course.

Reminder - Complete all of the Lesson 1 tasks!

You have reached the end of Lesson 1! Double-check the to-do list on the Lesson 1 Overview page to make sure you have completed all of the activities listed there before you begin Lesson 2.

Lesson 2: Economic, Environmental, and Societal Issues in Materials Science

Overview

Overview

In addition to fundamental materials properties, selecting which material to use in an application can be limited by a number of factors. Some of these factors include the cost of production, availability of starting materials (natural resources), level of pollution resulting from the manufacturing process, and amount of waste produced at the end of the lifecycle of the application. In this lesson, I will present relatively brief overviews of economic, environmental, and societal considerations that are important in the materials selection process.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Diagram the total materials life cycle, and briefly discuss relevant issues for each stage of the cycle.

- List the inputs and outputs for the materials life cycle analysis/assessment scheme.

- Cite issues that are relevant to the "green design" philosophy of product design.

- Discuss recyclability/disposability issues relative to the three primary classifications of solid materials and composite materials.

- List and briefly discuss three controllable factors that affect the cost of a materials product.

Lesson Roadmap

Lesson 2 will take us one week to complete. Please refer to the course calendar for specific due dates.

| To Read |

Read pp 25-36 (Ch. 2) in Introduction to Materials ebook Reading on course website for Lesson 2 |

|---|---|

| To Watch | Making Stuff: Cleaner |

| To Do | Lesson 2 Quiz |

Questions?

If you have general questions about the course content or structure, please post them to the General Questions and Discussion forum in Canvas. If your question is of a more personal nature, feel free to send a message to all faculty and TA's through Canvas email. We will check daily to respond.

Reading Assignment

Things to consider...

While you read the material for this lesson in your e-book and on the course website, use the following questions to guide your learning. Also, remember to keep the learning objectives listed on the previous page in mind as you learn from this text.

- What are the relevant issues for each stage of the total materials life cycle?

- What are the inputs and outputs for the materials life cycle analysis/assessment scheme?

- What is the "green design" philosophy of product design and how does it differ from the total materials life cycle paradigm?

- What are the recyclability/disposability issues relative to metals, ceramics, polymers, and composites?

- What are the three controllable factors that affect the cost of a materials product and how do they affect the cost?

Reading Assignment

Read pp 25-36 (Ch. 2) in Introduction to Materials ebook

Introduction

In this lesson, we're going to look at the economic, environmental, and societal issues of materials science. The textbook reading for this week will introduce these topics, while the additional text on this website will supplement the reading material and explore further the topics of green design and social justice with regard to materials. The video for this lesson, Making Stuff: Cleaner, explores the science and technology of making energy production and usage cleaner and more efficient. Materials development in generating, storing, and distributing energy towards creating a more sustainable future are highlighted in the video.

To Read

Read sections 20.1 - 20.4 in the customized e-book (answer quiz questions on those sections, and then return to this website).

Economic Considerations

First and foremost, a product must make economic sense. The price of a product must be attractive to customers, and it must return a sustainable profit to the company. To minimize product costs, materials engineers should consider three factors: component design, material selection, and manufacturing technique. Also, there could be other significant costs including labor and fringe benefits, insurance, profit, and costs associated with regulatory compliance. As the world has become more populated and that population is increasing its usage of the earth's natural resources, engineers are increasingly being asked to consider sustainable practices when developing new products. Also, since it is estimated that approximately half the energy consumed by the U.S. manufacturing industry is used to produce and manufacture materials, the efficient use of energy for manufacturing processes and utilization of sustainable energy sources when available is highly desirable.

Sustainability represents the ability to maintain an acceptable lifestyle at the current level and into the future while preserving the existing environment. Your textbook discusses one approach to achieving sustainability: green product design. In the next section, we will look at some green design principles and examples of their application. Before moving on to that section, please watch the following short video. This (1:53) video on using renewable feedstock to replace nonrenewable starting raw materials highlights a green design principle used to make processes more sustainable.

To Watch

The term renewable feedstock refers to raw material that can be grown or produced by humans. The usage of renewable feedstock is attractive because it reduces the amount of harmful waste produced from the crude oil refinery and distillation processes. Most print inks are made from crude oil derived pigments. If you think about the amount of printing that is done on a global scale, this can be a problem in the long term.

Currently in development are soy-based inks which are derived from the oil of the soybean plum. As a plum, soybeans are a renewable resource. The production process of these inks is overall more environmentally friendly then their petroleum-based counterparts. Also, these soy-based inks are much brighter than the petroleum-based inks.

The recycling process of paper products printed with soy-based inks is also considerably more environmentally friendly. When paper products are recycled, the ink needs to be removed. Petroleum inks can be difficult to remove, but soy-based inks can be removed with relative ease.

Components of Green Design

There are three primary components of green design: reduce, reuse, and recycle. The reduce concept means to redesign a product to use less material. The reuse concept means to fabricate a product using material that can be used again. Recycling refers to the concept of reprocessing a product at the end of its lifecycle into new raw material that can be processed into new products.

One green design principle is that if there is less waste produced, then there is less to clean up. Please watch the following short (2:23) video that highlights this principle.

To Watch

Another green design principle related to producing less waste is to produce waste that is biodegradable. Please watch the following short (2:06) video that highlights this green design principle.

To Watch

Some processes result in waste that is toxic or hazardous. The following video (2:04) showcases a genetically modified bacteria that has been developed to produce an enzyme that, when used with glucose, can replace a known carcinogen in a widely used synthesis process. In addition, the replaced chemical is derived from nonrenewable fossil fuels, while glucose is readily available, non-toxic, and renewable.

To Watch

For more efficient use of energy, synthesis processes should be designed to occur near room temperature and at atmospheric pressure to reduce the amount of energy used when possible. Heating, cooling, and increasing or decreasing pressure, requires energy. The following green chemistry principle video (1:26) discusses the advantages of designing your synthesis process to occur near room temperature and at atmospheric pressure.

To Watch

Recycling

Recycling of used products rather than disposing of them as waste is a desirable approach for several reasons. Recycled material replaces the need to extract raw materials from the earth. The energy requirements to process recycled materials are normally less, and in the case of aluminum much less, than the energy required to process extracted raw materials from the earth. In addition, recycling conserves natural resources and eliminates the ecological impact from the extraction of raw materials from the earth. Proper product design facilitates recycling, which reduces pollution emissions and landfill deposits.

Some issues surrounding recycling include that products must be disassembled or shredded to recover materials, and collection and transportation costs are significant factors in the economics surrounding recycling. The following video examines the anatomy of a properly designed landfill. After watching the video (4:39), proceed to your textbook and read section 20.5.

To Watch

To Read

Read section 20.5 in the customized e-book.

In the next sections, we will be discussing the recycling of metals, glass, polymers, paper, and limits of recycling.

Recycling of Metals

As mentioned in the e-book, aluminum is the most commonly recycled nonferrous metal. (Ferrous is Latin for iron, so a nonferrous metal is a metal which does not contain iron.) Aluminum is recycled because it takes a lot less energy to recycle aluminum than it takes to extract aluminum from bauxite ore, which requires heating and electrolysis. In addition, aluminum readily forms an oxide that forms a protective surface. This protective surface protects the bulk of the aluminum from oxidizing further. This results in most of the aluminum being recovered every time it goes to the recycling phase, in contrast to iron.

In the case of iron, oxidation, i.e., rust, does not protect iron from oxygen and water, and significant amounts of iron are not recyclable because the iron has been converted to rust. Please watch the following video (5:04) which summarizes the points about recycling of metals emphasized in your e-book and this website.

To Watch

In the next section, we will discuss recycling of ceramics, in particular, the recycling of glass which is the most common commercial ceramic.

Recycling of Glass

Glasses are the most common commercial ceramics, however, there is little economic incentive to recycle glass. The raw materials for producing glass are inexpensive and readily available. Glass is relatively dense, which makes it expensive to transport which adds to the costs of recycling. Glass must be sorted before being processed during recycling, usually done manually which adds to costs. Not all glass is recyclable, and the glass comes in many different forms. Please watch the following video (3:29) which summarizes the points about recycling of glass emphasized in your e-book and this website.

To Watch

In the next section, we will discuss some of the limitations of recycling.

Limits of Recycling

Recycling has a number of advantages. Properly done, it reduces the usage of raw materials, energy usage, air pollution, water pollution, and greenhouse gas emissions. There are, however, a number of limits to the effective implementation of recycling. Recycling can involve energy usage, hazards, labor costs, and practices by individuals and countries, which can hamper the efficient implementation of recycling plans. The biggest limit to recycling is that not all materials can be recycled and so materials can only be recycled a limited number of times due to degradation each time through the process. This degradation is referred to as downcycling.

In addition, recycling poses a number of societal and ethical issues. As highlighted in the e-book, e-waste recycling has led to electronic waste from developed countries being shipped to undeveloped countries for recycling. In many cases, this leads to low wages and terrible conditions for workers involved in the recycling process and the release of toxins which are environmental and health risks for the individuals and their surrounding communities. Please watch the following video (5:26) which summarizes the limits of recycling as discussed in your e-book and this website.

To Watch

In the next section, we will discuss the recycling of polymers, in particular, plastics.

Recycling Polymers

One way of classifying polymers is to break them up into two classes. The two classes of polymers are thermoplastic polymers and thermosetting polymers. The basic property that separates a thermoplastic polymer from a thermosetting polymer is the polymer’s response to being heated. When the thermoplastic polymer is heated, it melts, softens, and can be reformed when cooled. When the thermosetting polymer is heated, it hardens and cannot be reformed and stays hard when cooled. We will learn much more about each of these two classes of polymers and the reasons for their defining properties later in our lesson on polymer structures.

Since thermoplastic polymers can be melted and reformed, they are easily recycled. However, their properties do degrade with each reuse. Thermosetting polymers are much more difficult to recycle. Some of them can be ground up and used as filler for other processes, and, on a case-by-case basis, some can be processed to be broken down into their underlying base units which can be reused. Another approach to reducing the amount of plastic that ends up in our landfills is the development of biodegradable plastic. The idea here is that plastic can be made to breakdown (be compostable). In addition, bioplastics often come from renewable raw materials. But this leads to an ethical issue: do you use the available arable land for plastic or food production?

Now, please watch the following video (4:38) on plastics and biodegradable plastics which summarizes some of the issues around plastic recycling and bioplastics as discussed in your e-book and this website.

To Watch

In the previous video, the incineration of waste was discussed. Incineration leads to a huge volume reduction of waste, which results in less waste ending up in the landfill. Waste in the landfill is the least environmentally friendly option. However, incineration typically results in less recycling, which would be a more efficient use of recyclable material than incinerating it. This reduction of recycling due to incineration is considered the major disadvantage of incineration. Although an important concern with incineration is the production of toxins, with proper technology these toxins can be managed. A segment of the video for this week, Making Stuff: Cleaner, discusses burning waste to create electricity. Please watch the following short video (4:40) which discusses burning waste to create electricity as well as the issues regarding incineration discussed above.

To Watch

Lastly, please watch the following video (5:40) on the recycling of paper, which touches on several themes of this lesson including sustainability, downcycling, and green design principles.

To Watch

Video Assignment: Making Stuff Cleaner

Now that you have read the text and thought about the questions I posed, go to Lesson 2 in Canvas and watch the Making Stuff: Cleaner video (55 minutes). This video highlights some innovations in materials science that can potentially help make our technology use cleaner in the future. In "Making Stuff: Cleaner," in contrast to the readings of this lesson, the rapidly developing science and business of clean energy is explored. Some of the latest materials developments in generating, storing, and distributing energy are investigated in the hope of creating a sustainable future.

Video Assignment

Go to Lesson 2 in Canvas and watch the Making Stuff: Cleaner Video (55 minutes). You will be quizzed on the content of this video.

Summary and Final Tasks

Summary

Producing a sustainable society is one of the greatest challenges facing our society. The supply of natural resources, the creation of pollution during the manufacture of materials, recycling issues, and materials waste all issues of concern towards creating a sustainable society. By considering a material's total life cycle, utilizing materials life cycle analysis, and implementing a ‘green design’ philosophy, engineers can work towards alleviating some of these issues.

Reminder - Complete all of the Lesson 2 tasks!

You have reached the end of Lesson 2! Double-check the to-do list on the Overview page to make sure you have completed all of the activities listed there before you begin Lesson 3.

Lesson 3: Atomic Structure and Bonding

Overview

Electronic configuration for elements and the interatomic bonding between atoms and molecules determine some of the important properties of solid materials, including a correlation between bonding type and material classification—namely, ionic bonding (ceramics), covalent bonding (polymers), metallic bonding (metals), and van der Waals bonding (molecular solids). In this lesson, we will review briefly atomic structure, electron configurations in atoms, the periodic table, and atomic and interatomic bonding. These fundamental and important concepts will be applied to the understanding of solid materials in this and subsequent lessons of this course.

We will see in later lessons that important properties of solid materials depend on the way in which the atoms are arranged. In this lesson, we will consider some fundamental and important concepts about how the atoms are held together that compose a solid. These concepts: atomic structure, electron configuration, the periodic table, and the various types of primary and secondary interatomic bonds, are discussed with the assumption that the student has already encountered this material in a high school chemistry course.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Describe and compare the Bohr and wave mechanical atomic models.

- Describe the important quantum-mechanical principle that relates to electron energies.

- Recognize the effect of the Pauli exclusion principle on atomic structure.

- Produce the electronic configuration for the ground state of a given element and any ions.

- Identify the locations of metallic, non-metallic, and intermediate elements on the periodic table.

- Describe the general rule for electronegativity on the periodic table.

- Contrast the behavior of valence electrons for electropositive with the valence electrons of electronegative elements.

- Briefly describe ionic, covalent, metallic, hydrogen, and van der Waals bonds.

- Find examples of materials with the following bond types; ionic, covalent, metallic, hydrogen, and van der Waals bonds.

- Briefly explain the fact that water expands upon freezing to ice from its liquid phase.

Lesson Roadmap

Lesson 3 will take us 1 week to complete. Please refer to Canvas for specific due dates.

| To Read |

Read pp 37-65 (Ch. 3) in Introduction to Materials ebook Reading on course website for Lesson 3 |

|---|---|

| To Watch | Chapters from Hunting the Elements, TED-Ed talks on Atoms and Periodic Table |

| To Do | Lesson 3 Quiz |

Questions?

If you have general questions about the course content or structure, please post them to the General Questions and Discussion forum in Canvas. If your question is of a more personal nature, feel free to send a message to the instructor through Canvas email. The instructor will check daily to respond.

Reading Assignment

Things to consider...

While you read the material for this lesson in your e-book and on the course website, use the following questions to guide your learning. Also, remember to keep the learning objectives listed on the previous page in mind as you learn from this text.

- What is the main difference between the Bohr and the wave particle atomic models?

- How does the electronic configuration of an atom determine its materials classification?

- What are some of the materials properties that the location of the element on the Periodic Table predicts?

- How does bonding affect the materials properties of atoms and molecules?

- How does bonding type determine a material's probable materials characterization?

Reading Assignment

Read pp 37-65 (Ch. 3) in Introduction to Materials ebook

The Atom

The word atom is derived from the ancient Greek adjective atomos, meaning "uncuttable" or "indivisible." The earliest concepts of the nature of the atom were debated in ancient India and ancient Greece. We now know that the atom has a nucleus composed of protons and neutrons surrounded by clouds of electrons. The protons are positively charged, electrons are negatively charged, and neutrons possess no charge. Neutrons and protons are held in the nucleus by the nuclear force, and neutrons are not simply a proton plus an electron. In fact, neutrons are required to make the nucleus stable once you have more than one proton in the nucleus.

Atoms are the fundamental building blocks of matter; they cannot be divided using chemicals. Chemical reactions to move electrons can affect how atoms bind to each other but cannot be used to divide atoms. Most of the mass of the atom is located in the nucleus, with the mass of the proton roughly equal to the larger neutron, but 1840 times the mass of the electron. In contrast, most of the volume of the atom is filled with electrons. Now please watch this brief (5:22) video on the (brief) history of atomic theory.

To Watch

To Read

Now that you have watched the video, please go to your e-textbook and read the first four sections (pages 36 to 46 in Chapter 3 of Materials for Today's World, Custom Edition for Penn State University) of this lesson's reading. When finished with the reading proceed to the next web page.

The Periodic Table

The periodic table classifies the elements according to their electron configuration. The scientist given credit for the modern periodic table is Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev. Please watch the following video (4:24) which explains the true genius of what Mendeleev accomplished.

To Watch

As mentioned in the video the true power of Mendeleev’s periodic table was the predictive ability of his table. This concept is at the heart of science. Scientists cannot just model behavior, but are required to make predictions, which later can be verified or refuted, thus, providing a test for the validity of their model or theories. It is interesting to note that Mendeleev’s work in the 1870s preceded the discovery of the atom which occurred with J.J. Thompson’s discovery of the electron in 1897 and the later work on the nucleus after 1900.

To Read

Now proceed to your e-textbook and finish reading this lesson’s reading assignment (pages 47 to 64 in Chapter 3 of Materials for Today's World, Custom Edition for Penn State University). Please proceed to the next webpage when you have completed this reading assignment.

Bonding and Bonding Type - Material Correlations

As you've recently read, there are four principal bonding types: ionic, covalent, metallic, and van der Waals. Ionic bonding involves the exchange of electrons between atoms to complete shells, either by adding or giving up electrons. The resulting atoms are oppositely charged and attract each other, resulting in an ionic bond. Covalently bonded materials have bonds in which electrons are shared between atoms. In metallic bonding, a "sea of electrons" is uniformly distributed throughout the solid and acts as a glue to hold the atoms together. Van der Waals bonds are relatively weak compared to the other three principal bond types and result when attractive forces from permanent or induced dipoles form.

In addition, the reading noted a correlation between materials classification and bonding time. Ionic bonding is associated with ceramics, covalent bonding is associated with polymers, metallic bonding is associated with metals, and van der Waals bonding is associated with molecular solids. As we study materials in further detail in this course we will utilize these associations to explain observed materials properties in the different materials classifications. Before we proceed to this lesson’s video assignment, there are a couple of more topics that I would like to address. Your textbook highlighted water as a material of importance and its volume expansion upon freezing. We will explore this topic further in the next section.

Water (Its Volume Expansion Upon Freezing)

Water is an extremely important molecule for life as we know it. An uncommon property that water possesses is the fact that frozen water (ice) is less dense than liquid water. This effect occurs due to the structure that occurs when water is cooled to form ice. The following video (3:55) takes a lighthearted approach to explain why ice floats.

To Watch

Now that you have watched this video, please proceed to the next section which highlights van der Waals forces and the gecko’s ability to walk on ceilings.

How Do Geckos Defy Gravity?

Please watch the following video (4:29) which explains how geckos use van der Waals forces to walk on ceilings. While watching this video, see if you can answer the following question: how is the gecko’s ability to walk on ceilings an example of nanomaterials?

To Watch

So now that you have watched the video, can you see how this is an example of nanomaterials? A nanomaterial can utilize size and structure to perform unique abilities. The gecko utilizes van der Waals forces which operate on the scale of nanometers. In addition, the gecko utilizes the unique geometry of its feet to adhere to and release from surfaces. This is an example of using structure (or geometry) to perform a unique ability. At this time, please proceed to the lesson’s video assignment.

Video Assignment: Hunting the Elements

Video Assignment

Now please go to Lesson 3 in Canvas and watch chapters 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 from the NOVA "Hunting the Elements" documentary. You will be quizzed on the content of these videos.

Summary and Final Tasks

Summary

Presented in this lesson were several fundamental and important concepts—namely, atomic structure, electron configurations in atoms and the periodic table, and the various types of inter-atomic bonds that hold together the atoms that compose a solid. The various types of atomic bonding, which are determined by the electron structures of the individual atoms, along with geometric atomic arrangements can determine some of the important properties of solid materials. Later in the course, we will move to the next level of the structure of materials, specifically, to some of the geometric atomic arrangements that may be assumed by atoms in the solid state.

Reminder - Complete all of the Lesson 3 tasks!

You have reached the end of Lesson 3! Double-check the to-do list on the Lesson 3 Overview page to make sure you have completed all of the activities listed there before you begin Lesson 4.

Lesson 4: Mechanical Properties

Overview

Many materials are subjected to forces or loads when in use. In such situations, it is necessary to know the characteristics of the material and to design the member in order to avoid failure during the expected life and service environment of the material. Key mechanical design properties are stiffness, strength, hardness, ductility, and toughness. Factors to be considered include the nature of the applied load and its duration, as well as the environmental conditions. The applied loads could be tensile, compressive, or shear and their magnitudes may be constant with time or may fluctuate continuously. Application time may be only a fraction of a second, or it may extend over a period of many years. Service temperature may be an important factor. In this lesson, we will introduce how the various mechanical properties are measured and what these properties represent.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Define stress and strain.

- Define elastic region, plastic region, fracture point, elasticity, tensile strength, and the yield strength.

- Given a stress-strain diagram, determine elastic region, plastic region, fracture point, elasticity, tensile strength, and the yield strength.

- Distinguish between tensile, compressive, shear, and torsional stress.

- Define hardness, resilience, and toughness.

- Evaluate whether a material is ductile or brittle using a stress-strain diagram.

Lesson Roadmap

Lesson 4 will take us 1 week to complete. Please refer to Canvas for specific due dates.

| To Read |

Read pp 66-98 (Ch. 4) in Introduction to Materials ebook Reading on course website for Lesson 4 |

|---|---|

| To Watch | Making Stuff: Stronger |

| To Do | Lesson 4 Quiz |

Questions?

If you have general questions about the course content or structure, please post them to the General Questions and Discussion forum in Canvas. If your question is of a more personal nature, feel free to send a message to the instructor through Canvas email. The instructor will check daily to respond.

Reading Assignment

Things to consider...

When you read the web material for this lesson and e-book material for this lesson, use the following questions to guide your reading. Also, remember to keep the learning objectives listed on the Overview page in mind.

- What is the difference between stress and strain?

- Given a stress-strain diagram for material, how can one identify the elastic region, plastic region, fracture point, elasticity, and the yield strength?

- Given a stress-strain diagram for a material, how can you determine if the material is ductile or brittle?

- How do tensile, compressive, and shear stress differ?

- Do the terms stiffness, strength, hardness, ductility, and toughness mean the same to the general public as they do to materials scientists and engineers?

Reading Assignment

Read pp 66-98 (Ch. 4) in Introduction to Materials ebook

Tensile, Compressive, Shear, and Torsional Stress

As we can see in the above graphic, there are quite a few materials terms that are used when describing the properties of materials. In this lesson, we are going to define the above terms. It turns out that many of the above terms are related to the stress-strain curve of a material. What are stress and strain, and how are they related?

Let us take a cylinder and stress it. To stress it, I would fix one end of the cylinder and pull from the other end as shown in the figure below.

According to Newton's third law, the cylinder will experience a force downward on the lower surface of the cylinder and an equal and opposite force on the upper surface of the cylinder. My cylinder has an original length of Io and surface area of Ao. As I pull on my material with the force F the cylinder will lengthen and the resulting length will be l. Stress, σ, is defined as the force divided by the initial surface area, σ=F/Ao. This pulling stress is called tensile stress. Strain is what results from this stress. Strain, ε, is defined as the change in length divided by the original length, ε

If instead of pulling on our material, we push or compress our cylinder we are introducing compressive stress. This is illustrated in the following figure:

If instead of applying a force perpendicular to the surface, we apply parallel but opposite forces on the two surfaces we are applying a shear stress. This is illustrated in the following figure:

Stress related to shear is torsional stress. If we hold one end of our cylinder fixed and twist the other end as shown in the figure below, we are applying a torsional (or twisting) stress.

Examples of Materials Under Stress

If we look at a picture of a ski lift, we can see several different types of stress. The cable, highlighted in the box labeled A, is subject to tensile stress. The driveshaft, highlighted in the box labeled B, is experiencing torsional stress. The support pillar, highlighted in box labeled C, is subject to compressional stress. In the two figures below, the boulder is applying a compressive stress on the rock that is supporting it and the metal struts of the bridge are experiencing compressive stress while supporting the upper structure of the bridge.

Stress-Strain Testing

A typical stress-strain testing apparatus is shown in the figure above, along with the typical geometry of a tensile test specimen. During a tensile test, the sample is slowly pulled while the resulting change in length and the applied force are recorded. Using the original length and surface area a stress-strain diagram can be generated.

To Read

Now that I have introduced stress, please go to your e-textbook and read the first two sections (pages 65 to 70 in Chapter 4 of Materials for Today's World, Custom Edition for Penn State University) of this lesson's reading. When finished with the reading proceed to the next web page.

Elastic Region

What is the elastic region? It is the region where the material can be deformed and when released will return back to its original configuration. Many metals in the elastic region have a resulting strain that is proportional to the tensile load when the applied tensile load is small. Mathematically, this can be written as , and more generally is known as a form of Hooke's law. E is the proportionality constant and is called the modulus of elasticity or Young's modulus. Physically, the larger the value of the modulus of elasticity the stiffer the material is, i.e., the more resistant to bending the material is. If we look at a stress-strain diagram for a metal in the elastic region such as that shown in the figure below, the slope of the curve is the modulus of elasticity.

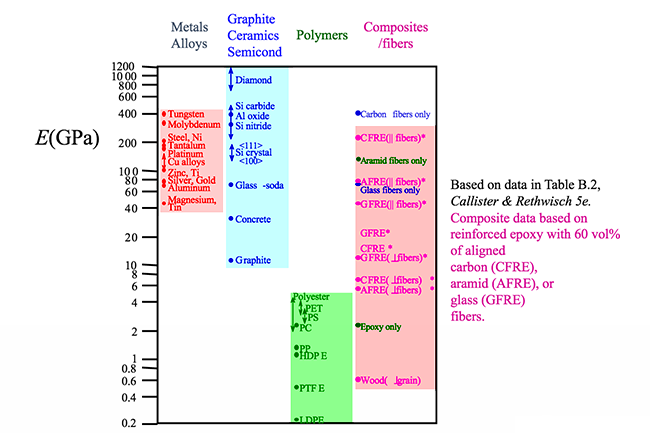

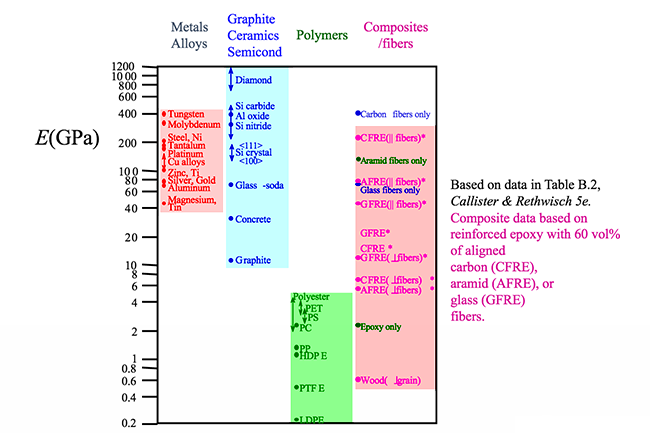

If we look at the figure below it is not surprising that the material listed with the highest E is diamond. Diamond has strong carbon bonds and is incredibly stiff. Larger E indicates a stronger bond. Later when we study composites in more detail, we will see that fibers are added to polymers to increase the stiffness of the material. Increased stiffness implies increased E, which you can see in the figure for the composite/fiber materials.

To Read

Now that you have been introduced to elasticity, please go to your e-textbook and read section 7.3 (pages 71 to 74 in Chapter 4 of Materials for Today's World, Custom Edition for Penn State University) of this lesson's reading. When finished with the reading proceed to the next web page.

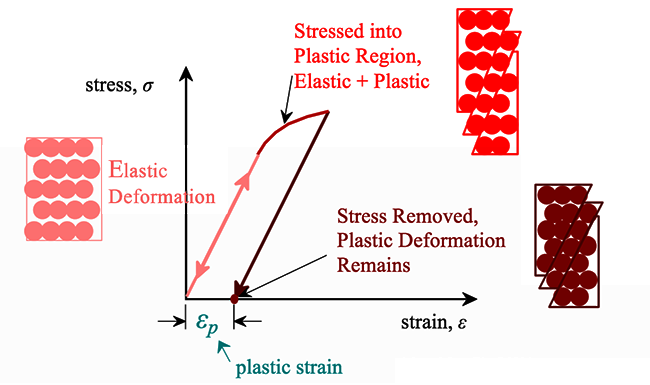

Plastic Deformation

For most metallic materials, the elastic deformation region is relatively small. At some point, the strain is no longer proportional to the applied stress. At this point, bonds with original atom neighbors start to break and reform with a new group of atoms. When this occurs and the stress is relieved, the material will no longer return to its original form, i.e., the deformation is permanent and nonrecoverable. The material has now moved into the region referred to as plastic deformation. In practice, it is difficult to identify the exact point at which a material moves from the elastic region to the plastic region. As shown in the figure below, a parallel line offset by 0.002 strain is drawn. Where that line intercepts the stress-strain curve is identified as the yield strength. The yield strength is equal to the stress at which noticeable plastic deformation has occurred.

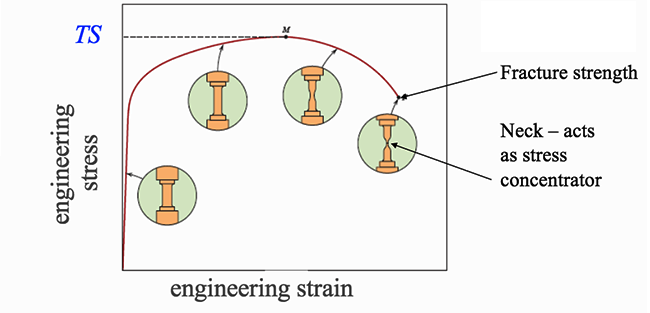

For many materials, the stress-strain curve looks like the curve shown in the figure below. As the stress is increased from zero, the strain increases linearly until it starts to deviate from linear at the yield strength. For increasing stress, the curve proceeds to a maximum, at which point it curves downward toward the fracture point. The maximum corresponds to the tensile strength, which is the maximum stress value for the curve and is indicated by M in the figure. The fracture point is the point at which the material ultimately breaks, indicated by F in the figure.

Resiliency and Toughness

When a person is resilient, we mean that they bounce back from change to their original personality. Resiliency in the material sense is similar. We can define resilience of the material to be the amount of energy the material can absorb and still return to its original state. If we are talking about stressing the material and having it return to its original state, we are talking about the material remaining in the elastic region of the stress-strain curve. It turns out that we can get the energy of elasticity by taking the area under the curve of the stress-strain curve. That area has been highlighted in the figure below, which is the area under the curve from the origin to the yield strength.

Toughness, in contrast to resilience, is how much energy can be absorbed and still keep going. One analogy that can be used when describing toughness is that of a car in a demolition derby. The car is allowed to continue the competition as long as it is capable of moving. It does not matter how many hits and how much destruction has been done to the car, but rather as long as the car can move it can stay in the competition. The toughness of the car is based on how many hits and how much damage the car can sustain and continue in the competition. In the case of materials, the amount of energy that the material can absorb plastically before fracturing is the toughness.

In the figure below, we can see that a material can have a high tensile strength (ceramics) and yet have a small toughness. In addition, materials can be extremely ductile (unreinforced polymers) and also have a small toughness. So, a large toughness (metals) is obtained by having a high tensile strength and a high ductility.

What is a Brittle Material?

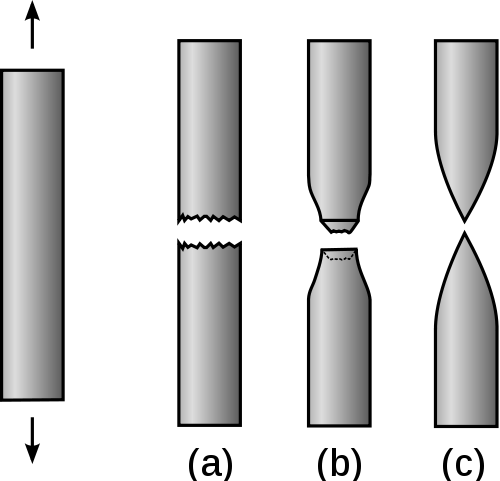

Brittle material breaks while little to no energy is absorbed when stressed. The material fractures with no plastic deformation. The material in the figure below marked with (a) shows what a brittle material will look like after pulling on a cylinder of that material. Typically, there will be a large audible snap sound when the brittle material breaks. A brittle material is also known as a material having low ductility. A stress-strain curve for brittle and ductile materials is shown in the figure below. We will talk more about ductile materials in the next section.

You may be asking: why are ceramics so much more brittle than metals? It has to do with the type of bonding. In metals, their metallic bonds allow the atoms to slide past each other easily. In ceramics, due to their ionic bonds, there is a resistance to the sliding. Since in ionic bonding every other atom is of opposite charge when a row of atoms attempts to slide past another row, positive atoms encounter positive atoms and negative atoms encounter negative atoms. This results in a huge electrodynamic repulsion which inhibits rows of ceramic atoms from sliding past other rows. In metals, the sliding of rows of atoms results in slip, which allows the metal to deform plastically instead of fracturing. Since in ceramics the rows cannot slide, the ceramic cannot plastically deform. Instead, it fractures, which makes it a brittle material.

Malleability and Ductility

Malleability and ductility are related. A malleable material is one in which a thin sheet can be easily formed by hammering or rolling. In other words, the material has the ability to deform under compressive stress.

In contrast, ductility is the ability of a solid material to deform under tensile stress. Practically, a ductile material is a material that can easily be stretched into a wire when pulled as shown in the figure below. Recall pulling is applying tensile stress.

If we pull on a rod of material, some of the possible profiles of the rods at fracture are shown in the figure below.

Profile (a) is an example of the material that fractures with no plastic deformation, i.e., it is a brittle material. Profile (b) is an example of a material that fractures after very little plastic deformation. These two profiles would be classified as having low ductility. Profile (c) in contrast is a material that plastically deforms before fracture. This material has high ductility. The stress-strain curves for the brittle, profile (a), and the ductile material, profile (c), are shown in the figure below.

To Read

Now that you have learned a bit about the mechanical behavior of metals, please go to your e-textbook and read pages 75 to 84 in Chapter 4 of Materials for Today's World, Custom Edition for Penn State University to learn more about this subject. When finished with the reading, proceed to the next web page.

Mechanical Behavior of Ceramics

It is difficult to measure the yield strength of ceramics as they tend to fracture before they enter the plastic deformation region, i.e., they are brittle. Examples of two brittle materials that fracture before entering the plastic deformation region are aluminum oxide and glass, as shown in the figure below.

Tensile tests of brittle ceramics are usually not performed. It is difficult to shape these materials into the proper test structure, difficult to grab the brittle material without breaking it, and it is difficult to align the test samples to avoid bending stresses which can destroy the sample. For brittle ceramics, a three-point bending apparatus (shown in the figure below) is used determine the stress-strain behavior, and the measurement results are used to calculate an equivalent modulus of elasticity.

To Read

Now that you have been introduced to the mechanical behavior of ceramics, please go to your e-textbook and read more on this topic on pages 84 to 86 in Chapter 4 of Materials for Today's World, Custom Edition for Penn State University. When finished with the reading proceed to the next web page.

Mechanical Behavior of Polymers

Polymers exhibit a wide range of stress-strain behaviors as shown in the figure below. The brittle polymer (red curve) elastically deforms and fractures before deforming plastically. The blue curve is a plastic polymer and is similar to curves for many metals. Its behavior begins in the linear elastic deformation region. As the curve transitions from the elastic to plastic deformation typically there is a peak stress. For polymer materials, this peak stress is identified as the yield stress. As the material is pulled further, fracture occurs. The stress value when fracture occurs is defined as the tensile strength for polymer materials. The tensile strength can be greater than, equal to, or less than the yield strength. The green curve is a class of polymers known as elastomers. These materials exhibit rubber-like elasticity and will return to their original shape and form unless they are extended to the point of fracture.

While some of the stress-strain curves for polymers might look similar to ones for metals, polymers are mechanically different than metals (or ceramics). A highly elastic polymer may stretch over 10 times the original length before breaking, while a metal might elastically stretch 10% of the original length elastically and may stretch plastically to double the original length before reaching its fracture point. As seen in the figure below, the largest elastic modulus values for polymers are well under the values for ceramics and metals.

As shown in the figure below, the tensile strength of some polymers can rival some ceramics but are no match for even the softest of metals.

To Read

Now that you have learned a bit about the mechanical behavior of plastics, please go to your e-textbook and read pages 87 to 89 in Chapter 4 of Materials for Today's World, Custom Edition for Penn State University to learn more about this subject. When finished with the reading, proceed to the next web page.

Hardness

Hardness is a measure of a material's ability to resist plastic deformation. In other words, it is a measure of how resistant material is to denting or scratching. Diamond, for example, is a very hard material. It is extremely difficult to dent or scratch a diamond. In contrast, it is very easy to scratch or dent most plastics. As shown in the diagram below, hardness increases from the very soft plastics to the incredibly hard diamond with most other materials ranging between.

A common method for measuring the hardness of a material is outlined in the figure below. A very hard-sphere is pushed with a set force into the material. The resulting indent is measured for width and depth. A harder material will have a smaller width and depth, i.e., smaller indentation. Larger hardness results in a high resistance to deformation from compressive loads, i.e., resistance to scratches and dents, and better wear properties.

To Read

Now that you have been introduced to the concept of hardness, please go to your e-textbook and finish the reading for this chapter (pages 90 to 97 in Chapter 4 of Materials for Today's World, Custom Edition for Penn State University). When finished with the reading proceed to the next web page.

Video Assignment: Making Stuff Stronger

Now that you have read the text and thought about the questions I posed, take some time to watch this 53-minute video about trying to find the strongest materials in the world. As you watch this video please pay particular attention to: (1) the ways that materials can be made stronger, (2) how stronger materials can be made lighter, cheaper, or better in other ways, and (3) how new stronger materials are designed for specific applications.

Video Assignment

Go to Lesson 4 in Canvas and watch NOVA's Making Stuff: Stronger Video. You will be quizzed on the content of this video. Skipped for Summer 2024 LEAP.

Summary and Final Tasks

Summary

In this lesson we discussed the stress–strain behaviors of metals, ceramics, and polymers and the related mechanical properties. Understanding and classifying the properties of materials allow us to design, produce, and utilize materials more efficiently and productively. In some cases, understanding materials allow us to utilize them for new applications. Lesson 4 provides us a language to discuss and compare different materials, while the previous lessons on the classification of materials and atomic structure along with upcoming lessons on the structure of materials will inform us regarding how geometric atomic arrangements and atomic structure can affect materials properties. In the next lesson, we will study how metal atoms arrange to form solids and some of the applications of metals.

Reminder - Complete all of the Lesson 4 tasks!

You have reached the end of Lesson 4! Double-check the to-do list on the Overview page to make sure you have completed all of the activities listed there before you begin Lesson 5.

Lesson 5: Structure and Applications of Metals

Overview

The crystal structure of a material can directly affect their properties. For example, gold and silver which share a common crystal structure are much less brittle than the metals beryllium and magnesium which possess a different crystal structure. Also, crystalline and noncrystalline materials of the same composition can possess significantly differing properties. In this lesson, we will discuss how structure can affect materials properties and also introduce imperfections, which can have major impacts on the properties of materials.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- List and explain the contributions to material processing made by the Egyptians.

- Explain the difference between melting and smelting.

- Distinguish between single crystals and polycrystalline materials.

- Describe the difference in atomic/molecular structure between crystalline and non-crystalline materials.

- Draw unit cells for face-centered cubic, body-centered cubic, and hexagonal close-packed crystal structures.

- Define polymorphism and allotropy.

- Sketch the three orthogonal crystal systems (cubic, tetragonal, orthorhombic) and the hexagonal crystal system with proper lattice parameter labels.

- Define isotropy and anisotropy with respect to material properties.

- List and describe the different types of imperfections in a crystal.

Lesson Roadmap

Lesson 5 will take us 1 week to complete. Please refer to Canvas for specific due dates.

| To Read |

Read pp 99-120 (Ch. 5) in Introduction to Materials ebook Webpages on this site for Lesson 5 |

|---|---|

| To Watch | Metal: The Secret Life of Materials |

| To Do | Lesson 5 Quiz |

Questions?

If you have general questions about the course content or structure, please post them to the General Questions and Discussion forum in Canvas. If your question is of a more personal nature, feel free to send a message to the instructor through Canvas email. I will check each of these daily to respond.

Things to Consider...

While you read the material for this lesson in your e-book and on the course website, use the following questions to guide your learning. Also, remember to keep the learning objectives listed on the previous page in mind as you learn.

- What contributions did the Egyptians make in the development of materials processing?

- What is the difference between melting and smelting?

- How do single crystal and polycrystalline material differ in grain structure?

- How do crystal and polycrystalline materials differ in their atomic/molecular structure?

- What is the difference between an amorphous and crystalline material?

- What is the difference between crystal structure and a crystal system?

Copper (Chalcolithic) and Bronze Ages

In the Neolithic Age, which was the period at the end of the Stone Age, the Egyptians were experiencing increasing population along with extensive food production capabilities, several communities in similar stages of development, and an extensive trade network with other civilizations. As the Egyptians entered the Copper and Bronze Ages, their technological advancements in gold, copper, and bronze processing were aided by their access to key natural resources. The figure below from the British Museum shows known natural resources of ancient Egypt.

In the following pages, we will discuss gold, copper, and bronze processing as developed by the Egyptians.

Egyptian Gold Processing

It is not surprising that gold was the first metal processed by the Egyptians. Very few metals are found in their native state, i.e., not bound to other elements in a compound such as a mineral. Copper is very rarely found in nature as an element and iron is typically only found as an element in some meteorites. Iron from meteorites was extremely rare in Egypt and was known as metal from the gods. Gold, however, is routinely found in nature as an element unlike copper and iron, and most other metallic elements. Gold, although rare, can be found as flakes or nuggets. As shown in the illustration below from an ancient Egyptian tomb, the Egyptians used charcoal and blow pipes to reach the temperatures needed to melt gold. Also, ‘slag’ (impurities) were skimmed off the molten gold.

The molten gold was poured into molds to form jewelry and other items. In addition, the Egyptians were able to hammer gold into very thin (5 µm) leafs. Gold is a malleable material. Malleability is a material’s ability to be deformed under compressive stress, i.e., to form a thin sheet by hammering or rolling. A ductile material (ability to be deformed under tensile stress, i.e. can be pulled into a wire) has to be a malleable material as well, but malleable materials do not have to be a ductile material. An example of this is lead. Lead is malleable but when pulled to form a wire it pulls apart. As you can see malleability and ductility are closely related but do not possess the same definition in material science.

The Egyptians believed gold to be a divine material which held magical powers. Electrum is an alloy of gold which is approximately 80% gold mixed with 20% silver. An alloy is a mixture of metals or a mixture of a metal with small amounts of non-metals. We will discuss metal alloys in more detail in the next lesson. In the next section, we will discuss Egyptian copper processing.

Egyptian Copper Processing

Native copper occurs in a very limited supply, so the start of the Copper Age is marked by the discovery of smelting copper from its ores which allows for a ready supply of copper. The two basic naturally occurring copper (II) carbonate minerals are pictured below.