Lesson 1: Materials Classification

Overview

In today’s society, virtually every segment of our everyday life is influenced by the limitations, availability, and economic considerations of the materials used. In this lesson you will be introduced to the interconnectivity of processing, structure, properties, and performance of the design, production, and utilization of materials; the role of materials scientists and engineers; and the three important criteria in materials selection. You will also be introduced to the classical classification of materials: metals, ceramics, and polymers, as well as, composites and the advanced materials classification used in modern high-tech applications.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Describe, with specific examples, the role of materials in human development during the Stone Age.

- List the six different property classifications of materials that determine their applicability.

- Cite the four components that are involved in the design, production, and utilization of materials, and briefly describe the interrelationships between these components.

- Describe the way in which scientists and engineers differ in their utilization of materials.

- Cite three criteria that are important in the materials selection process.

- List the three primary classifications of solid materials, and then cite the distinctive features of each.

- Briefly define smart material/system.

- Note the four types of advanced materials and, for each, its distinctive feature(s).

- Judge which material is most likely to be a promising candidate for utilization when given the primary or advanced material classifications of a list of candidate materials and one design selection criteria.

Lesson Roadmap

Lesson 1 will take us 1 week to complete. Please refer to Canvas for specific due dates.

| To Read |

Read pp 7-24 (Ch. 1) in Introduction to Materials ebook Reading on course website for Lesson 1 |

|---|---|

| To Watch | Secrets of the Terracotta Warriors |

| To Do | Lesson 1 Quiz |

Questions?

If you have general questions about the course content or structure, please post them to the General Questions and Discussion forum in Canvas. If your question is of a more personal nature, feel free to send a message to all faculty and TAs through Canvas email. We will check daily to respond.

Why Study Materials?

When materials scientist and narrator of The Secret Life of Materials videos (used in this course), Mark Miodownik, opens up the video on metal, he is at Piccadilly Circus in London, England. He marvels at how strange but wonderful it is that everything around him is man-made. This is not unique to London. A visit to the center of New York, Tokyo, Hong Kong, Beijing, Dubai, Paris, or any other 21st-century modern city would yield a similar situation. It might seem like a cliché but we are surrounded by materials. And with the range of materials available - whether it be in our professional or personal lives - we are constantly being asked to make choices about materials.

Something as routine and everyday as purchasing carbonated beverages is an example where materials choice could come into play. As we will see in the textbook, carbonated beverages can be purchased in glass, metal, or plastic containers. What factors drive manufacturers of carbonated beverages to offer their products in a range of different materials? What are the advantages and disadvantages when comparing the different materials choices for carbonated beverage containers? When selecting a material for a product there are many factors that must be taken into account, including properties, performance, and lifetime of the material; availability of raw materials; costs and energy usage in all steps of the processing; sustainability; waste disposal, etc.

Why is it important for you to understand materials? Products, devices, and components that you purchase and use are all made of materials. To select appropriate materials, and processing techniques for specific applications, you must have knowledge of the material properties and understand how the structure affects the material properties.

Throughout history, material advancement has gone hand-in-hand with societal advancements. The Stone Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age were all significant materials and societal periods in humankind's development. One question I would pose to you: what is today's materials age? Is it the polymer age? Or perhaps we have already advanced past that one. Are we in the age of silicon, i.e., the electronic materials age? Or, are we possibly moving into a nanomaterials age? A biomaterials age? Some might suggest that we moved into the information age or the digital age. In any of these cases, it is clear that the materials and the capability of the materials underlying these technologies are integral to the current and future capabilities in these areas.

Now let us explore how deep-seated materials are in our culture by looking back at materials in antiquity.

Materials in Antiquity

Three of the greatest ‘cultural’ revolutions occurred in antiquity, and they are named for the material use associated with these revolutions. They were predominantly bloodless, occurred over a millennium, and were revolutionary, not evolutionary. These three revolutions occurred during the Neolithic Age (part of the Stone Age), the Urban Age (Bronze Age), and the Iron Age.

Before we look at the Neolithic Age revolution, let’s take a look at the pre-Neolithic Age. If we look at the human timeline below we can see that the usage of stone tools began about 3.4 million years ago. This marks the beginning of the Stone Age, which lasted until the advent of metalworking and ended at different regions from ~9000 BCE to 2000 BCE. The genus Homo emerged during the Stone Age. The earliest usage of cooking, clothes, and fire occurred during this pre-Neolithic Age, with their earliest known dates shown in the figure below. In addition to cooking, fire was particularly important from a materials point of view. Fire was used for the tempering of wood arrowheads, annealing flint, and creating charcoal before the Neolithic Age, and has been an important component of materials processes throughout all ages of human existence.

The first of these revolutions was the Neolithic Revolution, which was highlighted by the transformation from a hunter/gatherer population to a farmer/skilled artisan population. It has been argued that three steps were required for the Neolithic Revolution: 1) hunter/gatherer population increase, 2) food production in marginal areas, and 3) several communities at similar stages of development. Near the end of the Stone Age, six civilizations emerged that satisfied these requirements.

| Millions of Years | Stage | Description |

|---|---|---|

| -10 | Hominids | Nakalipithecus (earlier apes) |

| -9 | Hominids | Ouranopithecus |

| -7 | Hominids | Sahelanthropus (earliest bipedal) |

| -6 | Hominids | Orrorin |

| -5 | Hominids | Human-like apes |

| -4.5 | Hominids | Ardiphithecus |

| -4 | Hominids | Early bipedal |

| -3.5 | Hominids | Australopithecus (earliest stone tools) |

| -3 to -2 | Homo habilis | |

| -2 to -.5 | Homo erectus | -2: Earliest exit from Africa, -1.5: Earliest fire use, -.6 Earliest cooking |

| -.5 to -.8 | Neanderthal | -.4: Earliest clothes |

| 0 | Home sapiens | Modern Humans |

Now we will take a closer look at the materials used during the Stone Age.

Flint (and Obsidian)

Flint and obsidian were very important Stone Age materials. Commonly found with chalk and limestone, flint is a form of the mineral quartz. Obsidian is a naturally occurring volcanic glass. Both were widely used in weapons and tools. As we will learn in this lesson, flint and obsidian are classic examples of ceramics. Both are hard and can be worked to produce a sharp edge, but both materials are prone to breakage. Slowly heating flint to 150 to 260 °C (300 to 500 °F), holding the temperature there for 24 hours (annealing), and then slowly cooling it back to room temperature, can relieve internal stresses which can improve the ability to produce flint tools or weapons with a sharper cutting edge. As discussed later, since flint is typically found with chalk and limestone, it is possible that the annealing of flint led to the discovery of lime mortar.

Charcoal

Charcoal is perhaps the greatest invention of the Paleolithic (Stone) Age. Charcoal is produced by partially burning organic matter (wood, bone, etc.) while limiting the supply of oxygen. One way of producing charcoal is to pile a large amount of wood, as shown in the figure, and covering it with soil to limit the amount of oxygen feeding the fire. During the burning process, considerable water is released, and at the completion of the burn, the wood is reduced to black brittle lumps of carbon (charcoal).

Charcoal played an important role throughout the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age. Why? Very few elements (noble metals and copper in very limited quantities) occur naturally in their pure form. Elements usually occur bound with other elements forming compounds, and typically occur in a mixture with other compounds. Heat is usually applied to break the compounds or melt the element to produce the raw material needed for manufacturing, such as copper and iron.

The temperatures required depend on the compounds and elements involved and can vary considerably. The temperatures obtainable by fire depend on the fuel used and the supply of air. If wood is used as the fuel in an open fire, temperatures in the fire might range from 350 to 500° C. Charcoal, being a denser and drier fuel source, can provide temperatures up to 800 °C under similar conditions. If the fire is confined, such as in a kiln or a furnace, and air is forced into the fire, it is possible to obtain even higher temperatures. For charcoal, it is possible to reach temperatures above 1000 °C.

Later, in our lesson on metals, we will see that this temperature is insufficient to melt pure iron, which is why the processing of impure iron (iron plus carbon) was developed first. Impure iron has a much lower melting temperature than pure iron. We will see that an advanced design furnace coupled with a hotter burning fuel source (coke, a form of coal) was needed to obtain pure molten iron.

Lime Mortar

When annealing flint, you can expect chalk or limestone to be present. Chalk and limestone are composed primarily of calcium carbonate (CaCO3), which is the same mineral present in hard water. It often shows up as a white residue on plumbing fixtures. If chalk or limestone is heated above 800° C (obtainable with charcoal), the gas carbon dioxide is released from the calcium carbonate leaving lime (CaO). Lime produced in this matter is referred to as quicklime or burnt lime. If water is added, this quicklime or burnt lime hydrates to form a white pasty substance known as slaked lime.

It is quite possible that an observant fire tender or cook could have noticed that, after encountering rain, this material would dry and form a hard substance. We refer to the substance as lime mortar, a type of cement. It is common to confuse the term cement with concrete. Cement is a binder or material that glues things together. Concrete, on the other hand, is a combination of cement and aggregate (sand, stone, etc.). Concrete is one example of a composite material. As we will see in this lesson a composite material is a material that is composed of two or more distinct materials in combination. Cement is the material within concrete that binds the stone and sand together.

In addition to the development of lime mortar in the Fertile Crescent, the Incas, and the Mayans independently discovered lime mortar around 5000 BCE, and it was widely used in ancient Rome and Greece around 4000 BCE.

'Plaster of Paris'

Originally, the term ‘plaster of Paris’ was coined in the 1700s to describe plaster produced from gypsum located outside of Paris. Over time, the term ‘plaster of Paris’ has become the generic term for gypsum-based plaster. Many ancient Egyptian tomb paintings are created on plaster. It is produced in a way that is similar to lime mortar, except gypsum is used in place of lime and much lower temperatures are needed. The resulting plaster is not as hard as lime mortar. Plaster vessels dating from 6000 BCE have been found from ancient Egypt.

Primary Civilizations

As mentioned before, near the end of the Stone Age, six civilizations that emerged that satisfied the requirements considered necessary for the Neolithic Revolution. If you look at the map below, you can see that there were two New World civilizations and four Old World civilizations, along with their names.

The four Old World civilizations had two very important advantages over the two New World civilizations. Namely, they were situated along great river systems and, being more numerous, had a more robust trade system in place. The great river systems were very important components in trade, but possibly of equal or greater importance was the benefit of annual flooding. Annual flooding reinvigorates farmland and, before the advent of modern farming techniques, allowed for the successful growth of crops year after year over multiple decades without the need for artificial fertilizers or crop rotation management schemes.

Two of the Old World civilizations, the Nile Valley and Mesopotamia, formed what has been called the Fertile Crescent, which is widely regarded as the birthplace of civilization. As can be seen in the figure below, both locations possessed great river systems and, due to their proximity, had well-established trade routes. At the close of the pre-Neolithic age, these two civilizations were experiencing increasing populations, had extensive food production capabilities, and had several communities at similar stages of development.

Mudbrick

The mudbrick was developed during the pre-pottery (Aceramic) Neolithic Age. Mudbricks were composed of a mixture that might have included clay, mud, loam, sand, and water mixed with a material to inhibit crumbling such as straw or rice husks. This was another example of a composite material. The ceramic material (clay, mud, loam, sand) by itself could support compressive loads but could be easily pulled apart. The second component of the composite, straw or rice husks, reinforced the first material, making it more difficult to pull the mudbrick apart. Water was used to allow the brick to be easily formed during manufacturing.

Since the early civilizations were located in warm regions with very limited timber, early bricks were sun-dried. The bricks needed to be dried before installation. Otherwise, shrinkage and cracking would occur that would destabilize the building.

Before the usage of bricks, structures were limited to wood and piling of stone. Creation of the brick unleashed creative design of buildings, and the architect was born! Clay or mud (raw material) was readily available everywhere, as was the strengthening material, straw or rice husks.

Later gravel and bitumen were used for stronger bricks. Bitumen is a naturally occurring (thermoplastic) polymer that, when heated, becomes a liquid and, when cooled, becomes solid. It is a black, tar-like substance with a consistency similar to cold molasses. Adding bitumen to bricks makes them both waterproof and much stronger. Bitumen is a mixture of hydrocarbons, which contains anywhere from 50 to thousands of carbon atoms. It is found in nature in rock asphalt, lake asphalt, and near other fossil fuels. In addition to being a structural improvement, bitumen, and crude oil sometimes found near bitumen deposits, provided fuel for brick kilns.

Pottery

The development of pottery in Mesopotamia was important for the storage of food protected from moisture and insects. Pottery takes clay and water which, in the proper proportions, form a mass that can be readily shaped. Once in the desired shape, the piece is dried to remove the water and then fired to improve mechanical stability. Clay was readily available and thus an inexpensive material to use.

Initially, unfired clay was used to line woven baskets. Although these unfired clay baskets were not particularly robust, they did provide much-needed waterproofing. Possibly, one of these early clay-lined woven baskets was discarded at the end of its usefulness. One could suppose that at some point the discarded basket was put into a fire to dispose of it. Later, in the cooled coals, someone could have discovered pottery shards and had the eureka moment where they realized that the firing of clay structures would produce pottery.

The development of pottery occurred in Mesopotamia around 7000 BCE. The invention of the pottery wheel occurred in Mesopotamia sometime between 6000 and 4000 BCE. The earliest ceramic objects (figurines) known have been found in what is now the Czech Republic and have been dated as being created between 29,000 and 25,000 BCE. The earliest pottery has been found in China and dates from around 18,000 BCE. In 10,000 BCE, Japan was using roping or coiling to produce pots. In the videos of this lesson, Secrets of the Terracotta Warriors, you will see that coiling was the method used to produce these warriors.

The Near East, at the end of the Neolithic Age (c.a. 4500 BCE), had mastered fire to produce and/or modify a number of materials. They had flint tools and weapons, buildings of mud brick with plaster finish, pottery, well-established trade routes from Mesopotamia to the Indus Valley, and a robust agrarian economy. Discussions about the Bronze Age and the Iron Age await us when we get to the lessons on metals and metal alloys. But now, let's take a look at what is materials science and engineering.

Materials Science and Engineering

In my experience in this course, students have difficulty understanding the difference between materials scientists and materials engineers. In the reading for this lesson, materials science is defined as investigating relationships between structures and properties of materials, and concern with the design/development of new materials. Materials engineering is defined as the creation of products from existing materials in the development of new materials processing techniques. I would restate the roles of material scientists and materials engineers as:

- Materials scientists study materials and create new materials.

- Materials engineers use materials and create new processes.

Now, these statements of the roles for material scientists and engineers are, of course, oversimplifications. As I think you will see in the following video (5:34) produced by the Penn State Department of Materials Science and Engineering we believe that cutting-edge materials research and development require a thorough understanding of both materials science and engineering.

To Watch

GARY L. MESSING: Materials Science and Engineering at Penn State is one of the larger departments of Materials Science in the country. By virtue of that, we are able to offer a full spectrum of research and teaching in the field of materials. We're strong in all aspects of materials - ceramics, metals, polymers, composites, semiconductors. That brings a certain uniqueness to the education of a Penn State graduate.

R. ALLEN KIMEL: We've tried to basically give the students a very strong core into the fundamentals of Materials Science and Engineering which are structure, property, relationships, but because of the breadth and depth of the expertise in this department they can choose to take courses that go towards the interest which brought them here in the first place. They could choose to focus on biomaterials or they could choose to focus on energy - it really allows a student to make their own Materials Science and Engineering degree.

ANGELA LEONE: Being at Penn State you get the large university feel where you are one in thousands of students at the same time you get the experience of the small college where everyone in the Materials department knows you by name. I'm currently studying the corrosion of nuclear waste glass fibers with Dr. Pantano. I found out that he's studying glass and I'm really interested in glass. So I just set up a meeting with him and about a week later he was showing me his labs. I think the most special thing I've done is to get involved in glass blowing. I really enjoy doing it it's very unique and I don't think I'd have that experience anywhere else. A lot of the professors look for undergrads to do research for them, to give them a feel and it helps you choose if you want to go on to grad school or go into industry.

JAME ADAIR: At any given time I'll have four to six undergraduates working in my laboratory. Right now I have about six. I bring both my research into my lectures for the undergraduates and my lectures into my research. The curriculum focuses on cutting edge technology. We also run a very strong research experience for undergraduate programs - it's a summer science program where we bring in undergraduates from all over the United States, including Penn State, into our laboratories. We're at the cutting edge in terms of early detection of cancer and much more benign delivery chemotherapeutics, as well as a host of new surgical instruments based on our ceramic powder processing.

R. ALLEN KIMEL: We even take it beyond; the department and this country, have our own international internship program. We have relationships with fourteen different universities in Europe and Asia and we send our students there to join research groups for a semester and actually perform research - so it's not a study abroad, take classes, but it's actually going there with a research question in mind and then joining a research group and actually performing that research. So it's getting involved in the research enterprise - and it's global.

STEPHEN WEITZNER: I've traveled to Germany with the department's International Internship in Materials Science Program. That was great; I was in Germany for seven months doing research at the Technical University of Darmstadt, where I was also doing some work with computational modeling and provided a nice background for coming back to campus and starting my senior thesis.

GARY L. MESSING: Materials at Penn State is actually a very big enterprise not only do we have the Department of Materials Science and Engineering, but we also have the Materials Research Institute The Institute represents all of the faculty on campus that are working in the field of materials. The Institute brings the strength of the community as well as the research facilities.

MICHAEL HICKNER: At Penn State, we have great opportunities for high-level research in Materials Science. Penn State has a long history in solving real-world problems in the industry, we have over a hundred million dollars of research that the entire university does with companies per year and we work with both large companies like General Electric and Dow Chemical Company as well as small startup companies either in State College or in Silicon Valley, and so I think that the research and the ideas here are flexible. We have a lot of unique capabilities.

JOAN REDWING: The research that we are doing at Penn State in the area of low dimensional materials is impacting the field of material science by providing new routes for the synthesis of low dimensional materials and also providing new insights into how these materials behave and ultimately how we can integrate them into devices. It feeds into other activities here at Penn State that are focused on the fabrication of devices so their faculty members in Electrical Engineering who are using the low dimensional materials to fabricate transistors or other types of electronic devices.

MICHAEL HICKNER: The material science that we do at Penn State is really creating new opportunities and pushing new frontiers in material science. Our research that we do in our labs every day makes a big difference to new types of batteries or new types of medical devices or new types of structural steels that had better corrosion resistance, or are harder, or more ductile. And so I think that we both make a difference in real-world problems, but also, we open up new ways to think about science and new ways to think about materials.

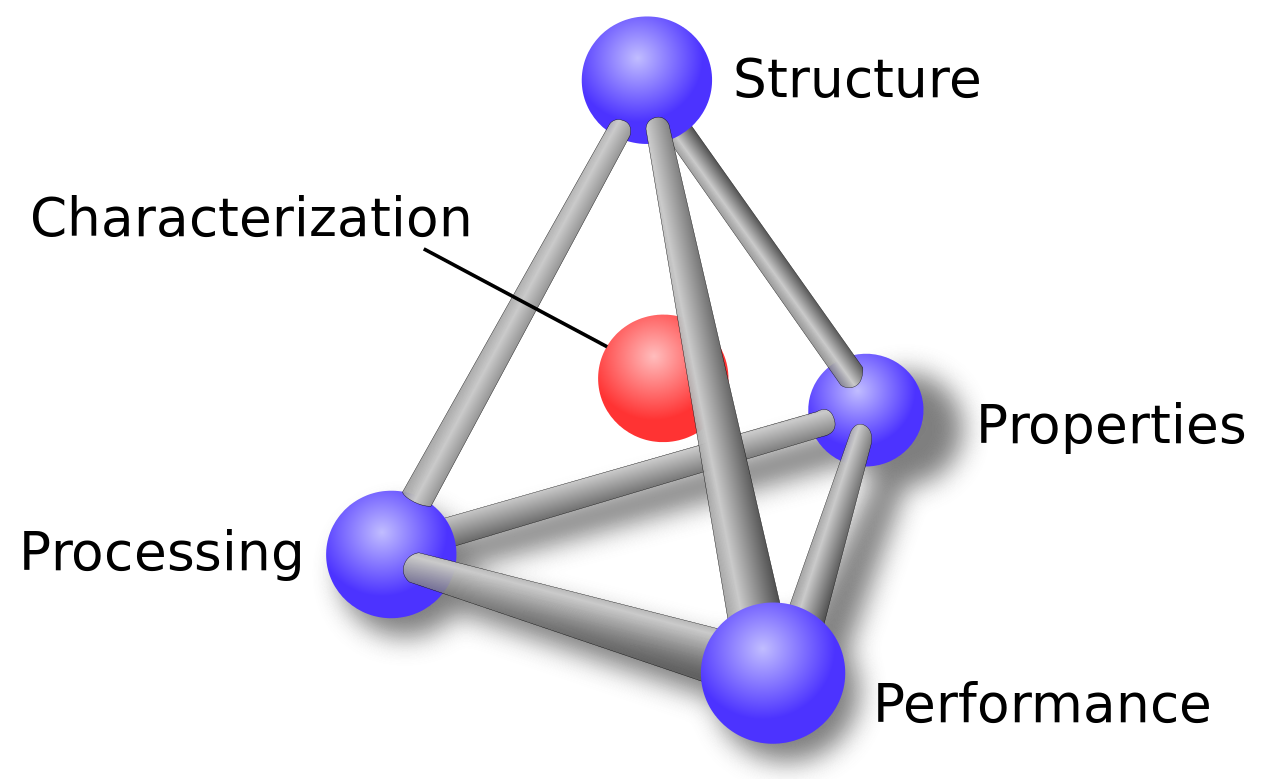

When utilizing a material, one needs to understand that the structure, properties, processing, and performance of the material are interrelated. This is represented by the materials science tetrahedron shown in the figure above. If one alters the processing, there is a direct connection with the structure, properties, and performance of the material. Adjusting any one of the factors will have varying degrees of impact on the other three factors. Characterization is the heart of the tetrahedron, signifying its role in monitoring the four components.

In this course, we will be looking at the four components (structure, properties, processing, and performance) of materials, beginning with properties. Properties of materials can be classified into six categories: mechanical, electrical, thermal, magnetic, optical, and deteriorative. We will start by looking at mechanical properties in lesson four and electrical properties in lesson 12. Unfortunately, we will not have time in this course to look at the other four properties. In lessons 3, 5, 7, and 8 we will look at the structure, both atomic and microstructure. Lesson 10 will be concerned with the processing of materials, and the performance of material will be addressed throughout the course.

Classification of Materials

Matter is composed of solid, liquid, gas, and plasma. In this course, we are going to be looking at solids which we will break down into three classical sub-classifications: metals, ceramics, and polymers.

In the reading for this lesson, representative characteristics of the three sub-classifications will be presented. In lesson three the chemical makeup and atomic structure will be further explored. The microstructure of the three classifications will be explored in their lessons.

Composites is a special additional classical sub-classification. Composites are composed of two (or more) distinct materials (metals, ceramics, and polymers) to achieve a combination of properties. Composites are introduced in this lesson in the reading and we will have a later lesson devoted to them as well. (Note: composites should not be confused with alloys. We will learn later that alloys are a mixing of a metal with other elements. In an alloy the elements are blended, they are no longer distinct components.)

Advanced materials are materials that are utilized in high-tech applications. These materials are typically enhanced or designed to be high-performance materials - many times with very specific tasks in mind.

Semiconductors are materials that can be made to switch from an insulator (off) to a conductor (on) by the application of voltage. The flow of electrons in semiconductors is somewhere between insulators, i.e., those that do not readily conduct electricity; and conductors, those materials which freely allow the flow of electrons. These materials have enabled our digital electronic age. The development of semiconductors for integrated circuits has allowed for the electronics and computer revolution that we have experienced in the last 50 years.

Nanomaterial, whose sizes typically range from 1 to 100 nanometers, are materials in which size and/or geometry can play a significant role in the dominant materials properties. In this size range, quantum mechanical effects can dominate, as well as, chemistry due to a large number of the atoms being surface atoms instead of atoms in bulk. In addition to size effects, these materials sometimes exhibit unique functionality due to their geometry. For example, gold nanoparticles can be very chemically active, unlike bulk gold. This effect is due to a large number of unsatisfied bonds on the surface of the gold nanoparticle.

Biomaterials are materials implanted into the body. In addition to performing their design function, they also have to have the ability to survive in the body (be biocompatible). The body can be a 'hostile' environment for materials. The body might attack the biomaterial as a foreign body (immune response) and the environment (wet and chemically active) in the body is typically one that leads to corrosion.

Smart materials are materials that are designed to mimic biological behavior. They are materials that, like biological systems, ‘respond to stimuli.' When determining whether a material system is utilizing a smart material, it is usually useful to identify the stimuli and the response that the material will exhibit, as well as, what biological system it is mimicking.

The readings and videos in the last two lessons of this course will explore advanced materials in more detail. Now that I have set the stage it is time for you to begin the additional reading for this lesson.

Reading Assignment

Things to consider...

When you read this chapter, use the following questions to guide your reading and always remember to keep the learning objectives listed on the overview page in mind.

- What are the materials' properties that determine materials applicability?

- What are the differences between material science scientists and engineers?

- What are the differences between metals, ceramics, and polymers?

- Does ‘best of both worlds’ apply to composites?

- Which of the materials classifications (metal, ceramics, polymers, composites, semiconductors, smart materials, biomaterials, and nanomaterials) are a distinct class of materials versus a group of materials with defining function composed of materials from distinct classes of materials?

Reading Assignment

Read pp 7-24 (Ch. 1) in Introduction to Materials ebook

Video Assignment: Secrets of the Terracotta Warriors

Now that you have read the text and thought about the questions I posed, take some time to watch this 54-minute video about determining how 8,000 terracotta warriors were manufactured in later third century BCE in China. As you watch this video, please note some of the problems that needed to be overcome and the assembly line approach that was necessary to complete everything in a two-year period.

Video Assignment

Go to Lesson 1 in Canvas and watch the Secrets of the Terracotta Warriors Video. You will be quizzed on the content of this video.

Summary and Final Tasks

Summary

Anthropologists, archeologists, and historians use the level of materials development (Stone Age, Bronze, Iron Age) to designate the stages of societal development. In today’s society, materials and materials development continue to shape development and advancement. In this lesson you were introduced to the important overarching themes of this course:

- materials scientists investigate the relationships that exist between the structures and properties of materials

- materials engineers design the structure of a material to produce a predetermined set of properties

- structure and properties are interlinked

- processing, structure, properties, and performance are interconnected

- environment, wear, and economics are three important criteria for materials selection

- classical classification of materials (metals, ceramics, and polymers, as well as, composites)

- and the advanced materials classification used in modern high-tech applications.

We will utilize the important concepts introduced in this lesson throughout the rest of the course.

Reminder - Complete all of the Lesson 1 tasks!

You have reached the end of Lesson 1! Double-check the to-do list on the Lesson 1 Overview page to make sure you have completed all of the activities listed there before you begin Lesson 2.