Lessons

This is the course outline.

Lesson 1: Getting Started

Overview

Overview

Meteorologists devote their lives to one purpose: to forecast the weather. But many other scientists work to build our understanding of the atmosphere, which is the basis for better prediction that meteorologists can use. Atmospheric science is the foundation upon which all meteorology is based.

Just as with all other physical sciences, mathematics is the language of atmospheric science. If you had our first-year meteorology course, you learned about weather forecasting and some of the physical basis behind the forecasts. This course will introduce you to even more physical concepts of atmospheric science and some of the mathematics that describe and quantify those physical concepts.

You have learned some of the mathematics that you need for this course and will be learning more about vectors and vector calculus soon. In this lesson, we will practice some of the mathematics. You will also prepare an Excel workbook that will help you with some of this course’s assessment problems.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- correctly use significant figures, dimensions, and units

- solve simple problems using integral and differential calculus

- prepare and use a course Excel workbook for course calculations

Questions?

If you have any questions, please post them to the Course Questions discussion forum. I will check that discussion forum daily to respond. While you are there, feel free to post your own responses if you, too, are able to help out a classmate.

1.1 The atmosphere is …

1.1 The atmosphere is …

The atmosphere is amazing, awe-inspiring, frightening, deadly, powerful, boring, strange, beautiful, and uplifting – just a few of thousands of descriptions. So much of our lives depend on the atmosphere, yet we often take it for granted.

Atmospheric science attempts to describe the atmosphere with physical descriptions using words, but also with mathematics. The goal is to be able to write down mathematical equations that capture the atmosphere’s important physical properties (predictability) and to use these equations to determine the atmosphere’s evolution with time (prediction). Predicting the weather has long been a primary focus, but, increasingly, we are interested in predicting climate.

We know quite a lot about the atmosphere. It has taken decades, if not centuries, of careful observation and insightful theory that is based on solid physical and chemical laws. We have more to learn. You could help to advance the understanding of the atmosphere, but you must first understand the physical concepts and mathematics that are already well known. That is a primary purpose of this course – to give you that understanding.

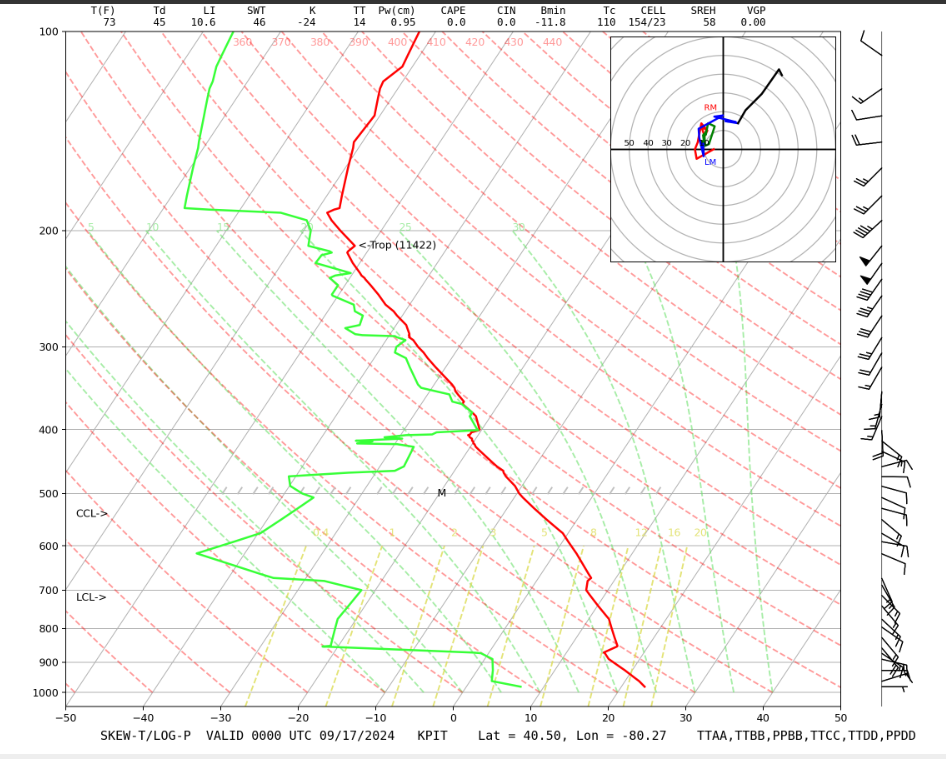

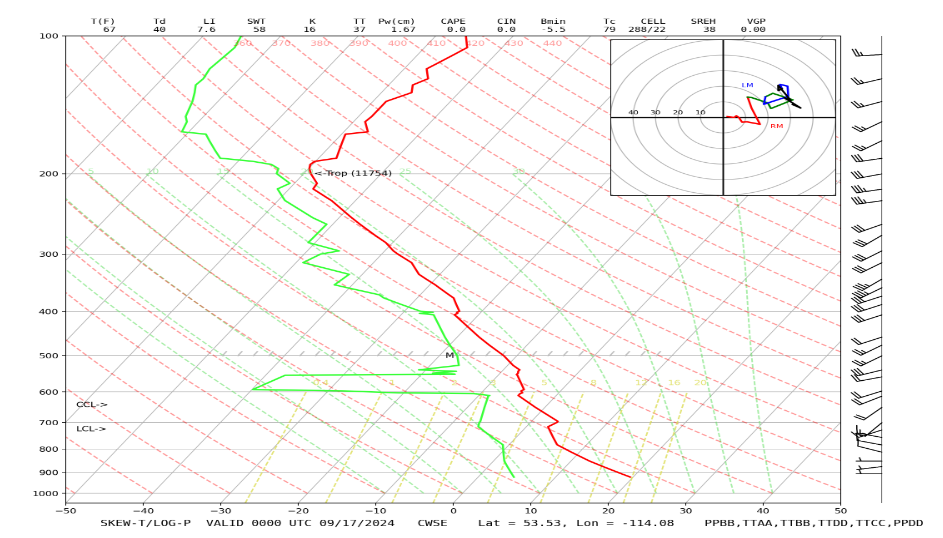

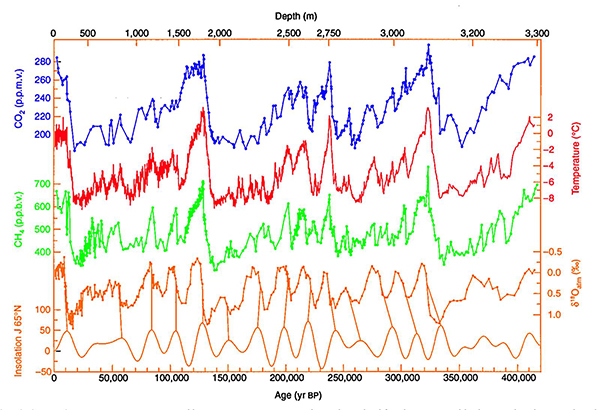

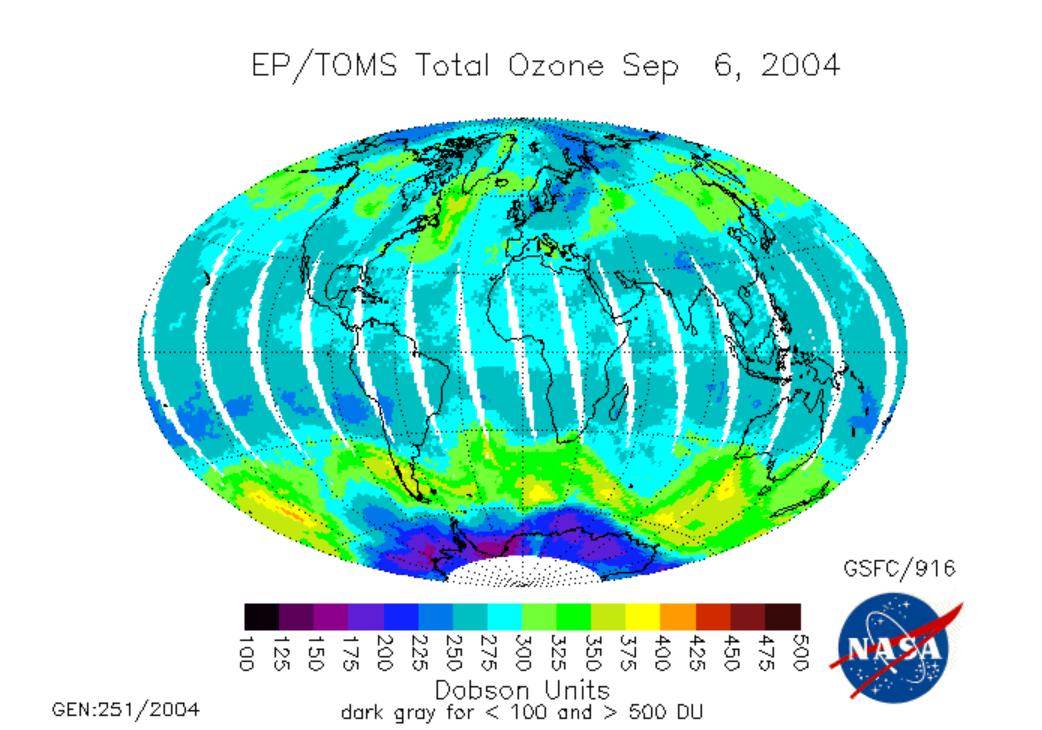

What follows, below, is a series of pictures and graphical images. Each one depicts some atmospheric process that will be covered in this course. Look at these images; you will see them again, each in one of the next ten lessons. Of course, in each observation there are many processes going on simultaneously. In the last lesson, you will have the opportunity to look at an observation and attach the physical principles and the mathematics that describe several processes that are causing the phenomena that you are observing.

Discussion Activity: Finding Errors

We have offered Meteo 300 online many times. However, there may still be errors despite our best efforts.

As we go through the course, if you find an error or typo, post it in the Finding Errors Discussion Forum in Canvas. If you are the first to find an error, you will be awarded 0.1 additional points on your final grade. If you aren't the first one to post, you receive no credit for your find, so it's a good idea to read each lesson at the beginning of each week. A student can earn up to 1 point total (i.e., by being the first to find an error ten times). Now, I hope that we have very few errors, but ...

1.2 You won’t believe what you can do with math!

1.2 You won’t believe what you can do with math!

You’ve been told many times that meteorology is a math-intensive field. It is. But for this course, you already know much of the math, and what you haven’t seen, you will see in vector calculus. To get ready for the meteorology and atmospheric science in this course, you will need to refresh your ability to solve simple math problems, including solving simple problems in differential and integral calculus. At the same time, we will remind you about the importance of correctly specifying significant figures and units in your answers to the problems. The goal of this first lesson is to boost your confidence in the math you already know.

How many figures should be in my answer?

Suppose you are asked to solve the following word problem:

In the radar loop, a squall line is oriented in the north-south direction and is heading northeast at 57 km hr-1. In the last frame of the loop, the line is 17 km west of the Penn State campus. You are out running and know that you can make it back to your apartment in 25 minutes. Will you get back to your apartment before you get soaked?

You reason that the line is moving northeast, and thus, at an angle of 45o relative to the east. Therefore, the eastward motion of the squall line is just the velocity times the cosine of 45o. That gives you the eastward speed. You decide to divide the distance by the eastward speed to get the amount of time before the line hits campus. You plug the numbers into your calculator and get the following result:

According to your calculation, you will make it back with 0.3 minutes (18 seconds) to spare. But can you really be sure that the squall line will strike in 25.3070 minutes? Maybe you should figure out how many significant figures your answer really has. To do that, you need to remember the rules:

Significant Figures Rules

- Non-zero numbers (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9) are ALWAYS significant.

- Zeroes are ALWAYS significant:

- between non-zero numbers

- SIMULTANEOUSLY to the right of the decimal point AND at the end of the number

- to the left of a written decimal point and part of a number 10

- In a calculation involving multiplication or division, multiply numbers as you see them. Then the answer should have the same number of significant figures as the number with the fewest significant figures.

- In a calculation involving addition and subtraction, the number of significant figures in the answer depends on the number of significant figures to the right of the decimal point when all the added or subtracted numbers are put in terms of the same power-of-ten. Add or subtract all the numbers. The answer has the same number of significant figures to the right of the decimal point as the number with the least number of significant figures to the right of the decimal point.

- The number of significant figures is unchanged by trigonometric functions. For other special functions:,

- Logarithms: When taking log of a number with X significant figures, the resulting value should have X number of digits to the right of the decimal point. We can generally apply the same rule for natural logarithms (ln).

- Anti-logarithms: When taking the anti-logarithm (eg. 10value) of a number with X values to the right of the decimal point, the resulting value should have X significant figures. We can generally apply the same rule for exponentials (e).

- Exact numbers never limit the number of significant figures in the result of a calculation and therefore can be considered to have an infinite number of significant figures. Common examples of exact numbers are whole numbers and conversion factors. For example, there are exactly 4 sides to a square and exactly 1000 m in a km.

- For multi-step calculations, any intermediate results should keep at least one extra significant figure to prevent round-off error. Calculators and spreadsheets will typically keep these extra significant figures automatically.

- When rounding, numbers ending with the last digit > 5 are rounded up; numbers ending with the last digit < 5 are rounded down; numbers ending in 5 are rounded up if the preceding digit is odd and down if it is even.

| Number(s) | Answer | Number of Significant Figures | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 2 | 25 has only 2 significant figures | |

| 8 | 1 | , round to 8 because 0.3 has only 1 significant figure | |

| 2 | , then drop 2 to get | ||

| 2 | , round up then drop 2 to get | ||

| 4.08 | 3 | , trim to 3 significant figures to get 4.08 | |

| 600 | 1 | 200. has 3 significant figures; 200 (no decimal point) has 1 but is ambiguous | |

| 90 | 2 | number in exponent has only 2 significant figures |

Check out this video (11:23): Unit Conversions & Significant Figures for a brief (1 minute) explanation of those rules! Start watching at 9:14 for the most relevant information. Note a minor error starting at 9:50 in which "60" should actually have a decimal point following the zero.

Now to the magic of figuring out how many sig figs your answer should have. There are two simple rules for this. If it's addition or subtraction it's only the number of figures after the decimal point that matters. The number with the fewest figures after the decimal point decides how many figures you can have after the decimal in your answer. So 1,495.2+1.9903 you do the math. First you get 1,497.1903 and then you round to the first decimal, because that first number only had one figure after the decimal. So you get 1,497.2. And for multiplication, just make sure the answer has the same sig figs as your least precise measurement. So 60 x 5.0839 = 305.034, but we only know two sig figs so everything after those first two numbers is zeroes: 300. Of course then we'd have to point out to everyone that the second zero but not the third is significant so we'd write it out with scientific notation: 3.0 * 10^2. Because science! Now I know it feels counterintuitive not to show all of the numbers that you have at your fingertips, but you've got to realize: all of those numbers beyond the number of sig figs you have? They're lies. They're big lying numbers. You don't know those numbers. And if you write them down people will assume that you do know those numbers. And you will have lied to them. And do you know what we do with liars in chemistry? We kill them! Thank you for watching this episode of Crash Course Chemistry. Today you learned some keys to understanding the mathematics of chemistry, and you want to remember this episode in case you get caught up later down the road: How to convert between units is a skill that you'll use even when you're not doing chemistry. Scientific notation will always make you look like you know what you're talking about. Being able to chastise people for using the wrong number of significant digits is basically math's equivalent of being a grammar Nazi. So enjoy these new powers I have bestowed upon you, and we'll see you next time. Crash Course Chemistry was filmed, edited, and directed by Nick Jenkins. This episode was written by me, Michael Aranda is our sound designer, and our graphics team is Thought Bubble. If you have any questions, comments or ideas for us, we are always down in the comments. Thank you for watching Crash Course Chemistry.

What are the typical types of variables?

There are two types of variables – scalars and vectors. Scalars are amount only; vectors also have direction.

Dimensions and units are your friends.

Most variables have dimensions. The ones used in meteorology are:

- L, length

- T, time

- Θ, temperature

- M, mass

- I, electric current

Some constants such as π have no units, but most do.

The numbers associated with most variables have units. The system of units we will use is the International System (SI, from the French Système International), also known as the MKS (meter-kilogram-second) system, even though English units are used in some parts of meteorology.

We will use the following temperature conversions:

We will use the following variables frequently. Note the dimensions of the variables and the MKS units that go with their numbers.

| Type | Variable | Dimensions | MKS Units | Common Unit Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scalar | length (x or ...) | L | m | |

| area (A) | L2 | m2 | ||

| volume (V) | L3 | m3 | ||

| speed (u, v, w) | L/T | m/s | ||

| energy (E) | ML2/T2 | kg m2/s2 | J = Joule | |

| power (P) | ML2/T3 | kg m2/s3 | W = Watt | |

| density (ρ) | M/L3 | kg/m3 | ||

| pressure (p) | M/LT2 | kg/ms2 | Pa = Pascal | |

| electrical potential | ML2/T3A | kg m2/s3A | V = Volt | |

| temperature (T) | Θ | K | ||

| Vectors | velocity (v) | L/T | m/s | |

| momentum (mv) | ML/T | kg m/s | ||

| acceleration (a) | L/T2 | m/s2 | ||

| force (F) | ML/T2 | kg m/s2 | N = Newton |

Pressure is used for many applications.

p = (normal force)/area = (mass x acceleration)/area = ML/T2L2 = M/LT2

1 Pa = 1 kg m–1 s–2; 1 hPa = 100 Pa = 1 mb = 10–3 bar (hPa = hecto-Pascal)

1013.25 hPa = 1.01325 x 105 Pa = 1 standard atmospheric pressure = 1 atm

Wind speed is another frequently used variable.

The knot (kt) is equal to one nautical mile (approximately one minute of latitude) per hour or exactly 1.852 km/hr. The mile is nominally equal to 5280 ft and has been standardized to be exactly 1,609.344 m.

Thus, 1 m/s = 3.6 km/hr ≈ 1.944 kt and 1 kt ≈ 1.151 mph.

surface winds are typically 10 kts ~ 5 m/s

500 mb winds are ~50 kts ~ 25 m/s

250 mb winds are ~100 kts ~ 50 m/s

Temperature is a third frequently used variable.

Kelvin (K) must be used in all physical and dynamical meteorology calculations. Surface temperature is typically reported in oF (or oC for METARS) and in oC for upper air soundings.

Water vapor mixing ratio is another frequently used variable.

Usually the units for water vapor mixing ratio are g kg-1. In the summer w can be 10 g kg-1; in the winter, it can be 1-2 g kg-1.

Dimensions truly are your friend. Let me give you an example. Suppose you have an equation ax + b = cT, and you know the dimension of b, x (a distance), and T (a temperature), but not a and c. You also know that each term in the equation – the two on the left-hand side and the one on the right-hand side – must all have the same units. Therefore, if you know b, you know that the dimensions of a must be the same as the dimensions of b divided by L (length) and the dimensions of c must be the same as the dimensions of b divided by Θ.

Also, if you invert a messy equation and you're not sure that you didn’t make a mistake, you can check the dimensions of the individual terms and if they don’t match up, it’s time to look for your mistake. Or, if you have variables multiplied or divided in an exponential or a logarithm, the resulting product must have no units.

So, how do you find the dimensions of units of an integral equation? One way to look at this problem is the figure out the dimension or the units of the integral's solution. Or, if you do not want to solve the integral, then you just assign the dimensions or units of each term in the integral expression, even the differentials such as dx, dt. The integrals symbols themselves have no dimensions or units. For example, take the integral of force over a distance, which is the integral of F dx. Pay no attention to the integral symbol. The dimensions of F are MLT-2 and the dimensions of dx are L, so when you multiply them together, you get MLT-2 *L = ML2 T-2, which has the same units as energy!

To find the dimensions or units of a derivative, the same thought process should be applied: either figure out the dimensions or units that the actual derivative would have, or if you do not want to solve the derivative, assign dimensions or units to every term in the equation that can have dimensions and units. For example, in dx/dt, dx is just a length and dt is just a time, so assign them those dimensions or units, which in this example is L/T or m/s. On the other hand, d/dt by itself has just the dimension of 1/T because the expression "d" has no units by itself. You now see that finding the dimensions or units for integral or derivative expressions is just as easy as for algebraic expressions.

Always write units down and always check dimensions if you aren’t sure. That way, you won’t crash your spacecraft on the back side of Mars [3]. View the following video (2:42).

Remember when NASA lost a spacecraft because it's simultaneously used Imperial and metric measurements on the same mission? The Mars Climate Orbiter disappeared 15 years ago this month and here's a very brief recap of exactly what went wrong. The Mars Climate Orbiter launched on December 11, 1998 on a mission to orbit Mars. This first interplanetary weather satellite was designed to gather data on Mars' climate and also serve as a relay station for the Mars Polar Lander, a mission that launched a few weeks later. But you can't just launched a spacecraft towards Mars and trust that it's going to get where it's going. You to have to monitor its progress. Many spacecraft have reaction wheels to keep them oriented properly and navigation teams behind interplanetary spacecraft that constantly monitor the angular momentum and adjust trajectory to make sure it gets exactly where it needs to go. In the case of the Mars Climate Orbiter, monitoring its trajectory and angular momentum involved a few steps. First, data from the spacecraft was transferred to the ground by telemetry. There it was processed by a software program and stored in an angular momentum desaturation file that process data was what scientists used to adjust the trajectory. Adjustments that were made by firing the spacecraft's thrusters. Every time the thrusters were fired, the resulting change in velocity was measured twice: once by software program on the spacecraft and once by software program off the ground. And here's where the problem comes in. It turned out that the two systems the processing software on the spacecraft and the software on the ground we're using two different units of measurements. The software on the spacecraft measured impulse, or the changes by thrusters in newton seconds a commonly accepted metric unit of measurement, while the processing software on the ground use the Imperial pound seconds. And it was unfortunately the ground computer's data that scientists used to update the spacecraft trajectory and because one pound of force is equal to 4.45 Newton's every adjustment was off by a factor of 4.45. For a spacecraft traveling tens of millions of miles to destination a number of seemingly small errors really add up. During the Mars Climate Orbiters nine-month cruise to Mars seven errors were introduced into its trajectory that meant that when it reached the red planet it was 105 miles closer to the Martian surface than expected. This turned out to be an unsurvivably low altitude for its Mars encounter when the spacecraft fire its main engine for the orbit insertion burn that was designed to put it into an elliptical orbit nothing happened. NASA lost contact quite abruptly with the spacecraft. So while we know the root cause of just what went wrong we'll never know exactly what happened to the Mars Climate Orbiter. The loss of the Mars Climate Orbiter very sadly happened in space. Leave your spacey questions and comments below, and don't forget to subscribe.

Quiz 1-1: Significant figures, dimensions, and units.

Now it's time to to take a quiz. I highly recommend that you begin by taking the Practice Quiz before completing the graded Quiz. Practice Quizzes are not graded and do not affect your grade in any way–except to make you more competent and confident to take the graded Quizzes : ).

- In Canvas, find Practice Quiz 1-1. You may complete this practice quiz as many times as you want. It is not graded, but it allows you to check your level of preparedness before taking the graded quiz.

- When you feel you are ready, take Quiz 1-1. You will be allowed to take this quiz only once. This quiz is timed, so after you start, you will have a limited amount of time to complete it and submit it. Good luck!

1.3 If you thought practice makes perfect, you could be right.

1.3 If you thought practice makes perfect, you could be right.

Calculus is an integral part of a meteorologist’s training. The ability to solve problems with calculus differentiates meteorologists from weather readers. You should know how to perform both indefinite and definite integrals. Brush up on the derivatives for variables raised to powers, logarithms, and exponentials. We will take many derivatives with respect to time and to distance.

Need Extra Practice?

Visit the Khan Academy website that explains calculus with lots of examples [5], practice problems, and videos. You can start with single variable calculus, but may find it useful for more complicated calculus problems.

Simple Integrals and Derivatives That are Frequently Used to Describe the Behavior of Atmospheric Phenomena

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

You have the power.

Often in meteorology and atmospheric science you will need to manipulate equations that have variables raised to powers. Sometimes, you will need to multiply variables at different powers together and then rearrange your answer to simplify it and make it more useful. In addition, it is very likely that you will need to invert an expression to solve for a variable. The following rules should remind you about powers of variables.

Laws of Exponents

If , then raise both sides to the exponent to move the exponent to the other side:

If , and you want to get an equation with a raised to no power, then raise both sides to the exponent :

This brief video (7:42) sums up these important rules:

In this video we're going to be talking about all of the basic rules of exponents. And remember, when we're talking about exponents we can have an exponent here like X to the fourth where x is the base what we call the base and four is the exponent this small number in the upper right hand corner. It means that we're going to multiply X by itself four times or it means we have four factors of X multiplied together. So, if we expand this out its x times X times X times X. if we collapse it its X to the fourth. So, what happens when we do addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division of exponents? Well, in all cases we have to be really careful about like terms. For example, when we add terms that have exponents in them together both the bases and the exponents have to be the same in order for us to add them together. So, if we look at this first example 3x squared plus 2x squared the base here is X and the base here is X so the bases are the same which is good because we need that. and the exponents we have 2 and 2 which is good because we also need the exponents to be the same in order to add these together. So basically we have 3x squared added to 2x squared is going to give us five of them, 5x squared. So, if you're going to do addition and subtraction the bases and the exponents have to be the same. In this case we have X to the third plus x squared our bases X are the same but our exponents are different we have three and two. These are not like terms, so we can't add these together we can't simplify this at all. What happens when we do subtraction well again we're looking for similar basis so we have X and X for our base and then we have exponents of four and four. So because the bases and the exponents of the scene we can combine these like terms. We have six of them were subtracting and applied one of them which is going to leave us with five of them. So 5 times X to the fourth, but in this problem despite having the same base they will have a base of X we have different exponents we have a 4 and a 3 and because we're doing subtraction we can't combine these. We can't simplify this at all. What happens when we multiply two values together where exponents are involved? Well, here in order to simplify all we care about is that the bases are the same. The exponents do not have to be the same. So here we have base X and base X and we know already that's all we need to multiply these together it doesn't matter that the exponents are also the same we just add them. So we have three times to these are coefficients on our x squared terms. We multiply those together. So three times two is six, so that's going to be the first part and then we have x squared times x squared. And if we look at that x squared times x squared what we're going to do is add the exponents together. And the reason is because if we expand these out we know that x squared is two factors of X multiplied together. We're multiplying that by another x squared, so we're multiplying that by two more factors of X multiplied together. All together this is X to the fourth. Which we know because this essentially becomes the rule x to the a x x to the B is X to the a plus B. We just add the exponents together. So two plus two is four we get X to the fourth. Here's another example we have X to the third times x squared remember there's an implied one coefficient in front of both of these when we multiply 1 x 1 we get one so there will be a implied one coefficient on our final answer. x cubed + x squared. We just care that the bases are the same and they both have a base X so we know will be able to multiply them together. We have X to the third times x squared and remember that is going to be X to the three plus two so when we simplify we get X to the fifth and that should make sense because we have 3 factors of x x 2 factors of X adding them all up we get five factors of X so X to the fifth. The quotient rule for exponents tells us that in the same way as when we multiplied we didn't have to have the same exponent. When we divide we also don't have to have the same exponent we only care about the bases so here we have like basis. We have base X for both of these the exponents happened to be the same but that doesn't matter we're just going to leave this six and our final answer, so we'll get six here. And then what we're going to do is subtract the exponent in the denominator from the exponent in the numerator so the result is going to be X to the 4 minus 4. This is the four from the numerator this is the four from the denominator. 4-4 is 0 so we get 6 x 20 x to the 0 is 1 so this is 6 times 1 or just six. Even if we have different numbers again we only care about the bases both of these have the same base of X so again we'll just keep our two and our final answer and then we'll have X to the 4-3 because we say numerator exponent minus denominator exponent. That's going to give us 2 times X to the 4 minus 3 is 1. so X to the first which is of course just equal to 2x. What about a power raised to another power or an exponent raised to another exponent? Well, just like before in this example here when we said X to the fourth means multiply X by itself four times here we're saying multiply x squared by itself three times. So this is going to be equal to x squared times x squared times x squared and now we're really just back at this right here for multiplying like bases together and we add the exponents. So, this is just the same as X to the two plus two plus two. Two plus two plus two is six so we get x to the sixth power. What we realize then is that we can expand this and then add the exponents together using this rule over here or we can just multiply these two exponents together. Two times three gives us six and so we can do it that way as well. We can even do this when we have a negative base. So this problem here is telling us multiply 3 factors of negative x squared together so this is going to be negative x squared times negative x squared times negative x squared. We can deal with the negatives separately. Remember we can cancel every two negatives and they become a positive so negative and negative become a positive we're just left with this single negative sign here. so our answer will be negative and then x squared times x squared times x squared we know is X to the sixth. You can also think about it this way when you have this negative sign inside the parentheses. It's the same thing as saying negative 1 times x squared all raised to the third power and then you can apply this exponent to the negative 1 negative 1 times negative 1 times negative 1 is going to give you negative 1 which is this part right here. And then x squared to the third is going to be X to the 60 you get this X to the sixth and when you multiply them together you get negative x to the sixth. So those are just some of the most basic exponent rules that you need to know.

Are you ready to give it a try? Solve the following problem on your own. After arriving at your own answer, click on the link to check your work. Here we go:

Check Your Understanding

What does y equal?

Quiz 1-2: Solving integrals and differentials.

Now it's time to to take another quiz. Again, I highly recommend that you begin by taking the Practice Quiz before completing the graded Quiz, since it will make you more competent and confident to take the graded Quiz : ).

- Go to Canvas and find Practice Quiz 1-2. You may complete this practice quiz as many times as you want. It is not graded, but it allows you to check your level of preparedness before taking the graded quiz.

- When you feel you are ready, take Quiz 1-2. You will be allowed to take this quiz only once. This quiz is timed, so after you start, you will have a limited amount of time to complete it and submit it. Good luck!

1.4 Are you ready to get with the programming?

1.4 Are you ready to get with the programming?

Meteorologists and atmospheric scientists spend much of their time thinking deep thoughts about the atmosphere, the weather, and weather forecasts. But to really figure out what is happening, they all have to dig into data, solve simple relationships they uncover, and develop new ways to look at the data. Much of this work is now done by programming a computer. Many of you haven’t done any computer programming yet, and for those of you who have, congratulations – put it to good use in this class. For those who are programming novices, we can introduce you to a few of the concepts of programming by getting you to use Excel or another similar spreadsheet program.

To help you learn and retain the concepts and skills that you will learn in this course, you will solve many word problems and simple math problems. For several activities, we give you the opportunity to practice solving particular types of problems enough times until you gain confidence that you can solve those same types of problems on a quiz. That means that you will be solving some types of problems several times and only the numbers for the variables will change. The simplest way for you to solve these problems is to program a spreadsheet to do that repetitive math for you.

Screenshot shows an Excel Spreadsheet

A text box says "put activity number in row 1" and an arrow points to cell A1.

A second text box says "put variable names in row 2" with an arrow pointing to cells A2 and B2

A third text box says "start numbers for variables in row 3" with an arrow pointing to cells A3 and B3

A final text box says "calculations follow variable numbers" with an arrow pointing to C3.

Let’s do a simple example. Suppose we have several boxes, some with different shapes and sizes, and we want to calculate the volume of the boxes and find the total volume. I have put in the names of the variables (with units!) and then the numbers for the length, width, and height of each box type and the total number of each box. To calculate the volume of each box, click on E3 and put an “= a3*b3*c3” in the equation line. Hit enter and it will do the calculation and put the answer in E3. A small square will appear in the lower right corner of E3. Click on this square with the mouse and pull down over the next three rows. Excel will automatically do the calculations for those rows. To calculate the total volume, go to F3 and enter “=d3*e3,” and hit “enter.” Grab the small box and pull down to get the total volume of each type of box. To get the total volume, click on F7, click on “Formulas,” and then “AutoSum,” and finally “Sum.” Excel will show you which cells it intends to sum. You can change this by adjusting the edges of the box it shows. Finally, pay attention to significant digits in your calculated volumes. You can adjust the number of decimal places by highlighting a cell or group of cells and then by clicking on the appropriate icon on the Excel tool bar. Note that an incorrect number of significant figures is displayed in some of the answers--see if you can figure out where.

| length (m) | width (m) | height (m) | number of boxes | box volume (m3) | total volume (m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.72 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 3 | =A3*B3*C3 | |

| 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 4 | ||

| 1.2 | 0.85 | 1.01 | 1 | ||

| 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.95 | 2 |

| length (m) | width (m) | height (m) | number of boxes | box volume (m3) | total volume (m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.72 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 3 | 0.19 | 0.58 |

| 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 4 | 0.14 | 0.56 |

| 1.2 | 0.85 | 1.01 | 1 | 1.03 | 1.03 |

| 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.95 | 2 | 0.37 | 0.73 |

Hopefully this example is a refresher for most of you. For those who are totally unfamiliar with Excel, please click on the question mark in the upper right of the screen and type in the box “creating your first workbook.” You can also visit Microsoft's help page for additional step-by-step instructions for how to Use Excel as Your Calculator [9]. The best way to learn, after the introduction, is by doing. The Keynote Support website [10] also lists helpful summaries of instructions.

Activity 1-3: Setting up your Meteo 300 Excel workbook.

Please follow the instructions above for setting up an Excel workbook. You will be using this workbook to do calculations, plot graphs, and answer questions on quizzes and problems for the rest of the course.

Use the same headings and the same numbers in the first four columns. Enter your own equations and find the box volumes and total volumes.

This assignment is worth 15 points. Your grade will mostly depend upon showing that you set up the workbook, but some additional points will be assigned contingent upon how well you follow the instructions. When your Excel workbook is complete, please do the following:

- Make sure that the file for your workbook follows this naming convention: Workbook_your last name (i.e., Smith)_your first name_(i.e., Eileen).xlsx.

- In Canvas, find Activity 1-3: Setting up your Meteo 300 Excel workbook. Upload your Excel workbook there.

Summary and Final Tasks

Summary

There is a very good reason that you are taking this class and I am teaching it – all of us are fascinated by the weather, awed by the atmosphere’s power, and passionate about learning more about it. Quite honestly, I can’t imagine a more rewarding career than the one that you are embarking upon or the one that I have. Nothing could be more rewarding than saving lives by making the atmosphere more predictable or by making the perfect prediction. Nothing.

But, do you know what? The best forecasters are the ones who can not only read weather maps, but who also know physically what the atmosphere is doing. The best forecasters know how to translate the physics into mathematics so that hand-waving can be turned into usable numbers. This course will start to make all of these connections between observations and physical cause-and-effect and help us find numerical solutions to questions.

For those of you who are in related disciplines, this course will give you a solid basic understanding of the atmosphere that you can apply in your studies and career, whether it be civil engineering, mechanical engineering, environmental engineering, chemistry, hydrology, or many other fields.

We have now reviewed some important concepts like significant figures and dimensions and units. You will continue to gain confidence in using the differential and integral calculus that you already know. As you go through the course, I want you to look back at the pictures of the atmosphere and imagine which equations are governing the processes that are causing your observations.

Reminder - Complete all of the Lesson 1 tasks!

You have reached the end of Lesson 1! Make sure that you have completed all of the tasks in Canvas.

Lesson 2: Thermodynamics

Overview

Overview

The atmosphere is composed of billions of billions of molecules, 1043 molecules to be exact. Each molecule is zooming at hundreds of meters per second but colliding with other molecules each billionth of a second, exchanging kinetic energy (½ mv2), momentum (mv), and internal energy (rotations and vibrations). It’s impossible to calculate what all of these molecules will do, so instead we study the energy and energy changes of volumes of molecules and use this information in our forecast models. This study is called thermodynamics. Thermodynamics has some difficult concepts to master, but it is also part of your everyday experience. In this lesson, you will learn the fundamental laws of thermodynamics and see how they describe our atmosphere’s pressure and temperature structure. You will learn why the atmosphere is sometimes stable and what happens when it isn’t.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- use the fundamental gas laws - Ideal Gas Law, Dalton’s Law – to determine the relative densities of different air masses

- derive the hydrostatic equilibrium equation from force balance to show why atmospheric pressure decreases with height

- use the 1st Law of Thermodynamics and conservation of energy (i.e., adiabatic processes) to explain air parcel temperature changes

- determine stability for different dry environmental temperature profiles

- calculate buoyancy and vertical velocity with time

Questions?

If you have any questions, please post them to the Course Questions discussion forum. I will check that discussion forum daily to respond. While you are there, feel free to post your own responses if you, too, are able to help out a classmate.

2.1 Gas Laws

2.1 Gas Laws

Understanding atmospheric thermodynamics begins with the gas laws that you learned in chemistry. Because these laws are so important, we will review them again here and put them in forms that are particularly useful for atmospheric science. You will want to memorize these laws because they will be used again and again in many other areas of atmospheric science, including cloud physics, atmospheric structure, dynamics, radiation, boundary layer, and even forecasting.

Looking Ahead

Before you begin this lesson's reading, I would like to remind you of the discussion activity for this lesson. This week's discussion activity will ask you to take what you learn throughout the lesson to answer an atmospheric problem. You will not need to post your discussion response until you have read the whole lesson, but keep the question in mind as you read:

This week's topic is a hypothetical question involving stability. The troposphere always has a capping temperature inversion—it's called the stratosphere. The tropopause is about 16 km high in the tropics and lowers to about 10 km at high latitudes. The stratosphere exists because solar ultraviolet light makes ozone and then a few percent of the solar radiation is absorbed by stratospheric ozone, heating the air and causing the inversion. Suppose that there was no ozone layer and hence no stratosphere caused by solar UV heating of ozone.

Would storms in the troposphere be different if there was no stratosphere to act like a capping inversion? And if so, how?

You will use what you have learned in this lesson about the atmosphere's pressure structure and stability to help you to think about this problem and to formulate your answer and discussions. So, think about this question as you read through the lesson. You'll have a chance to submit your response in 2.6!

Ideal Gas Law

The atmosphere is a mixture of gases that can be compressed or expanded in a way that obeys the Ideal Gas Law:

where p is pressure (Pa = kg m–1 s–2), V is the volume (m3), N is the number of moles, R* is the gas constant (8.314 J K–1 mole–1), and T is the temperature (K). Note also that both sides of the Ideal Gas Law equation have the dimension of energy (J = kg m2 s–2).

Recall that a mole is 6.02 x 1023 molecules (Avogadro’s Number). Equation 2.1 is a form of the ideal gas law that is independent of the type of molecule or mixture of molecules. A mole is a mole no matter its type. The video below (6:17) provides a brief review of the Ideal Gas Law. Note that the notation in the video differs slightly from our notation by using n for N, P for p, and R for R*.

So here I have a tank filled with gas. And these little dots represent some of the gas particles that would be in this tank. The arrows I put in here because all of these particles are in constant random motion. They're like a bunch of hyperactive little kids, running into each other all the time, banging into the sides of the container, and so forth. So we've got this tank of gas. Let's think about the characteristics that we could use to describe it. So one of the things that we could do is we could say what its temperature is. The higher the temperature, remember, the faster these gas particles are moving around, so temperature is very important when we talk about gas. Temperature for gases should always be reported in Kelvin. So we could say, for example, that the temperature of this guy here is 313 Kelvin. That's how hot these gas particles in the sample are. When you talk about gas, another important characteristic is pressure. How hard are these gas particles bouncing against the sides of the tank? How much pressure are they exerting on them? And we could measure these with a pressure gauge or something like that on the top of this tank. We could say, the pressure for this is 3.18 atm. That might be a pressure. And another thing that we spend a lot of time talking about when it comes to gas is volume. And again, I have these letters here that are how each one of these things are abbreviated. Volume, V, volume of this tank might be something like 95.2 liters. And finally, look at these particles that I've drawn. There is a certain amount of gas that's in here. And the amount of gas, which is abbreviated by the little letter n, is usually reported in moles, which is a convenient measure of how much of something we have. So we could say that the amount of gas in this tank is 7.5 moles. Now, whenever we have a sample of gas like this, if it's a tank or it's in a balloon or wherever it is, we can describe-- we can give it these various characteristics. And it turns out that also, for any sample of gas, if we know three of these characteristics, we can figure out what the fourth is. All we need to do is know three. And in order to do that, we use an equation that's a representation of the Ideal Gas Law. And it's written as P times V, pressure times volume, equals n, the amount of gas, times R times T, temperature. I'll get to R in a second. Don't worry about it for right now. It's going to be a number that we know. So let's say, for example, that we didn't know what pressure was, but we still knew the temperature, volume, and the amount of gas. No big deal. We could take the equation, PV equals nRT, and rearrange it. Divide both sides by V. Get rid of the V. And then we'd have P equals nRT divided by V. Plug these values in, and we could figure out what the pressure was. Or let's say that we knew what the pressure was of a particular gas sample. We know what the temperature was in a volume. But we didn't know what the amount of gas was. We don't know how much we had. We could figure out that fourth characteristic by rearranging the Ideal Gas Law for n, canceling out R and T on one side, rearranging it to solve for n. And then we could plug in the pressure, the volume, and the temperature, and we could figure out the amount of gas. So in other words, if we know three of these characteristics, we can always figure out what the fourth is. So you may be asking yourself, so R-- what's R? R is what we call a constant. It's a number that we know ahead of time that doesn't depend on the variables in our problem. The R that I'm going to be using most of the time for the videos is 0.0821 liters times atm divided by Kelvin times moles. Now notice that this is a fraction. It has both a top and a bottom. And it also is not just a number, but it has units. And check this out-- the units on R match the units in my problem. They match the characteristics that I'd be using. So I have liters here, liters here, atm, atm, Kelvin, Kelvin, and moles, moles. You always want the units on R to match the units of the characteristics in your Ideal Gas Problem. So because you always want the units to match, there are also different values of R, although I'm going to be using this mostly for the videos I'm doing. For example, let's say that instead of atm, I was using a pressure that was in millimeters of mercury. In this case, I wouldn't want to use this R here. I'd want to use this R here, so that the units match-- millimeters of mercury here, millimeters of mercury here, and the number's different-- 62.4. So again, that's what I use here. Let's say that instead of millimeters of mercury, my pressure was given to me in kPa. I would then use this value of R so that the units match. I've got kPa here, kPa here, and all the others are the same, so 8.31 for that. Now as I keep saying, in most of the videos that I'm going to be doing, I'm going to be using this top R with atm. But you may be asked by your teacher to use a different R. It's no big deal. That's probably just because they're giving you problems that have different pressure units, and they want the pressure units to match. So don't worry at all if you're using one of these other R's. Setting up and solving the Ideal Gas Law is exactly the same. No matter which of these R's you use, it's just a matter of plugging a different R in at the very end. So no matter which one you're using, you should be able to follow all these lessons, and it should all make sense.

Usually in the atmosphere we do not know the exact volume of an air parcel or air mass. To solve this problem, we can rewrite the Ideal Gas Law in a different useful form if we divide N by V and then multiply by the average mass per mole of air to get the mass density:

where M is the molar mass (kg mol–1). Density has SI units of kg m–3. The Greek symbol ρ (rho) is used for density and should not be confused with the symbol for pressure, p.

Thus we can put density in the Ideal Gas Law:

Density is an incredibly important quantity in meteorology. Air that is more dense than its surroundings (often called its environment) sinks, while air that is less dense than its surroundings rises. Note that density depends on temperature, pressure, and the average molar mass of the air parcel. The average molar mass depends on the atmospheric composition and is just the sum of the mole fraction of each type of molecule times the molar mass of each molecular constituent:

where the i subscript represents atmospheric components, N is the number of moles, M is the molar mass, and f is the mole fraction. This video (3:19) shows you how to find the gas density using the Ideal Gas Law. You will note that the person uses pressure in kPa and molar mass in g/mol. Since kPa = 1000 Pa and g = 1/1000 kg, the two factors of 1000 cancel when he multiplies them together and he can get away with using these units. I recommend always converting to SI units to avoid confusion. Also, note that the symbol for density used in the video is d, which is different from what we have used (ρ, the convention in atmospheric science).

Hey guys how do you solve ideal gas law questions involving density? The key is to have a formula or know how to derive the formula on your own. Remember density is mass over volume. Now, the way that mass is found in the ideal gas law equation is in n because the number of moles is the same as mass over molar mass. So, check this set. I'm going to replace n with mass over molar mass, and then I'm going to rearrange for m over v. I'm going to undo division by molar mass on the other side and then I'm going to undo multiplication by RT and bring my V over. Here's a what I mean. P times the molar mass divided by RT gives me mass over volume. Mass over volume is density and so my equation is density equals pressure times molar mass divided by RT. We can now use this equation to find the density of oxygen at 55 Celsius and a hundred and three kilopascals. So let's do it. The density is pressure that's 103 kilopascals times molar mass for oxygen. That's 32 grams per mole. R, now, I'm going to put my volume in liters and I'm going to put my pressure in kilopascals which means the relevant are that I want is 8.314 liters, kilopascals per mole Kelvin and my temperature in Kelvin is the temperature in Celsius plus 273, which gives me 328 Kelvin. And all of these units should cancel out to give me a density unit. Kelvin cancels of Kelvin per moles cancel / moles kilopascals canceled the scale pascals and left with grams per liter. Let's do this on the calculator 103 times 32 divided 8.314 divided 328. That's 1.21 grams per liter. That may not seem like a lot, but remember you're dealing with the gas here. If you have a 1-liter balloon how much is it actually going to weigh? Probably the amount of the rubber plus like a gram or so. This here is the density of oxygen gas at 55 and 103 kilopascals. This is your density formula in terms of the ideal gas law. Be able to use it. Best of luck!

Solve the following problem on your own. After arriving at your own answer, click on the link to check your work.

Example

Let’s calculate the density of dry air where you live. We will use the Ideal Gas Law and account for the three most abundant gases in the atmosphere: nitrogen, oxygen, and argon. The mole fractions of the gases are 0.78, 0.21, and 0.01, respectively. M is the molar mass of air; M = 0.029 kg mol–1, which is just an average that accounts for the mole fractions of the three gases:

R* = 8.314 J K–1 mol–1. Here, p = 960 hPa = 9.6 x 104 Pa and T = 20 oC = 293 K.

Putting these values into the equation 2.3, we get that the dry air density is 1.1 kg m–3.

What would the density be if the room were filled with helium and not dry air at the same pressure and temperature?

Helium density = (pressure times molar mass of helium)/(Ideal Gas Law constant in SI units times temperature in K) = 0.16 kg m–3

Dry Air

Often in meteorology we use mass-specific gas laws so that we must specify the gas that we are talking about, usually only dry air (N2 + O2 + Ar + CO2 +…) or water vapor (gaseous H2O). We can divide R* by Mi to get a mass-specific gas constant, such as Rd = R*/Mdry air.

Thus, we will use the following form of the Ideal Gas Law for dry air:

where:

.

Mdry air is 0.02897 kg mol–1, which is the average of the molar masses of the gases in a dry atmosphere computed to four significant figures.

Note that p must be in Pascals (Pa), which is 1/100th of a mb (a.k.a, hPa), and T must be in Kelvin (K).

Water Vapor

We can do the same procedure for water vapor:

where .

Typically e is used to denote the water vapor pressure, which is also called the water vapor partial pressure.

Dalton’s Law

This gas law is used often in meteorology. Applied to the atmosphere, it says that the total pressure is the sum of the partial pressures for dry air and water vapor:

Imagine that we put moist air and an absorbent in a jar and screw the lid on the jar. If we keep the temperature constant as the absorbent pulls water vapor out of the air, the pressure inside the jar will drop to pd. Always keep in mind that when we measure pressure in the atmosphere, we are measuring the total pressure, which includes the partial pressures of dry air and water vapor.

So it follows that the density of dry air and water vapor also add:

Check Your Understanding

Suppose we have two air parcels that are the same size and have the same pressure and temperature, but one is dry and the other is moist air. Which one is less dense?

We can solve this one without knowing the pressure, temperature, or volume. Let’s assume that 98% of the molecules are dry air, which means the remaining 2% are dry air in the first case and water vapor in second case. Dry air is 0.029 kg mol–1 and water vapor is 0.018 kg mol–1, so 2% of the moist air is lighter than the 2% of dry air, and when we consider the total air, this means that for the same temperature and pressure, moist air is always less dense than dry air.

Virtual Temperature

Suppose there are two air parcels with different temperatures and water vapor amounts but the same pressure. Which one has a lower density? We can calculate the density to determine which one is lighter, but there is another way to do this comparison. Virtual temperature, Tv, is defined as the temperature dry air must have so that its density equals that of ambient moist air. Thus, virtual temperature is a property of the ambient moist air. Because the air density depends on the amount of moisture (for the same pressure and temperature), we have a hard time determining if the air parcel is more or less dense relative to its surroundings, which may have a different temperature and amount of water vapor. It is useful to pretend that the moist parcel is a dry parcel and to account for the difference in density by determining the temperature that the dry parcel would need to have in order to have the same density as the moist air parcel.

We can define the amount of moisture in the air by a quantity called specific humidity, q:

We see that q is just the fraction of water vapor density relative to the total moist air density. Usually q is given in units of g of water vapor per kg of dry air, or g kg–1.

Using the Ideal Gas Law and Dalton’s Law, we can derive the equation for virtual temperature:

where T and Tv have units of Kelvin (not oC and certainly not oF!) and q must be unitless (e.g., kg kg–1).

Note that moist air always has a higher virtual temperature than dry air that has the same temperature as the moist air because, as noted above, moist air is always less dense than dry air for the same temperature and pressure. Note also that for dry air, q = 0 and the virtual temperature is the same as the temperature.

Solve the following problem on your own. After arriving at your own answer, click on the link to check your work.

Check Your Understanding

Consider a blob of air (Tblob = 25 oC, qblob = 10 g kg–1) at the same pressure level as a surrounding environment (Tenv = 26 oC and qenv = 1 g kg–1). If the blob has a lower density than its environment, then it will rise. Does it rise?

We will use equation 2.10. Remember to convert T from oC to K and q from g kg–1 to kg kg–1!

We see that the blob is less dense than its environment and so will rise. This difference of 0.6 oC may seem small, but it makes a huge difference in upward motion.

The following are some mistakes that are commonly made in the above calculations:

- not converting from oC to K:

We calculate that Tvblob < Tvenv, which is the wrong answer.

- not converting q from g/kg to kg/kg:

We calculate that Tvblob > Tvenv, which is correct in this case, but the numbers are crazy! After you complete your calculations, if the numbers you get just don’t seem right—like these—then you know that you have made a mistake in the calculation. Go looking for the mistake. Don’t submit an answer that makes no sense.

Once we find Tv, we can easily find the density of a moist parcel by using equation 2.5, in which we substitute Tv for T. Thus,

Quiz 2-1: What will that air parcel do?

This quiz will give you practice calculating the virtual temperature and density using the Excel workbook that you set up in the last lesson.

- Go to Canvas and find Practice Quiz 2-1. You may complete this practice quiz as many times as you want. It is not graded, but it allows you to check your level of preparedness before taking the graded quiz. I strongly suggest that you enter the equations for density and for virtual temperature in your Excel worksheet and use them to do all your calculations of density and virtual temperature on both the practice quiz and the quiz.

- When you feel you are ready, take Quiz 2-1. You will be allowed to take this quiz only once. This quiz is timed, so after you start, you will have a limited amount of time to complete it and submit it. Good luck!

2.2 The Atmosphere’s Pressure Structure: Hydrostatic Equilibrium

2.2 The Atmosphere’s Pressure Structure: Hydrostatic Equilibrium

The atmosphere’s vertical pressure structure plays a critical role in weather and climate. We all know that pressure decreases with height, but do you know why?

The atmosphere’s basic pressure structure is determined by the hydrostatic balance of forces [17]. To a good approximation, every air parcel is acted on by three forces that are in balance, leading to no net force. Since they are in balance for any air parcel, the air can be assumed to be static or moving at a constant velocity.

There are 3 forces that determine hydrostatic balance:

- One force is downwards (negative) onto the top of the cuboid from the pressure, p, of the fluid above it. It is, from the definition of pressure [18],

[2.11]

- Similarly, the force on the volume element from the pressure of the fluid below pushing upwards (positive) is:

[2.12]

- Finally, the weight [19] of the volume element causes a force downwards. If the density [20] is ρ, the volume is V, which is simply the horizontal area A times the vertical height, Δz, and g the standard gravity [21], then:

[2.13]

By balancing these forces, the total force on the fluid is:

This sum equals zero if the air's velocity is constant or zero. Dividing by A,

or:

Ptop − Pbottom is a change in pressure, and Δz is the height of the volume element – a change in the distance above the ground. By saying these changes are infinitesimally [22] small, the equation can be written in differential [23] form, where dp is top pressure minus bottom pressure just as dz is top altitude minus bottom altitude.

The result is the equation:

This equation is called the Hydrostatic Equation. See the video below (1:18) for further explanation:

Consider an air parcel at rest. There are three forces in balance, the downward pressure force, which is pressure times area in the parcel's top, and an upward pressure force on the parcel's bottom, and the downward force of gravity actually on the parcel's mass, which is just the acceleration due to gravity times the parcel's density times it's volume. The volume equals the parcel's cross sectional area times its height. We can sum these three forces together and set them equal to 0 since the parcel's at rest. Notice how the cross sectional area can be divided out. The next step is to put the pressure difference on the left hand side. And then shrink the air parcel height to be infinitesimally small, which makes the pressure difference infinitesimally small. By dividing both sides by the infinitesimally small height, we end up with an equation that's the derivative of the pressure with respect to height, which is equal to minus the parcel's density times gravity. This equation is the hydrostatic equation, which describes a change of atmospheric pressure with height.

Using the Ideal Gas Law, we can replace ρ and get the equation for dry air:

We could integrate both sides to get the altitude dependence of p, but we can only do that if T is constant with height. It is not, but it does not vary by more than about ±20%. So, doing the integral,

H is called a scale height because when z = H, we have p = poe–1. If we use an average T of 250 K, with Mair = 0.029 kg mol–1, then H = 7.3 km. The pressure at this height is about 360 hPa, close to the 300 mb surface that you have seen on the weather maps. Of course the forces are not always in hydrostatic balance and the pressure depends on temperature, thus the pressure changes from one location to another on a constant height surface.

From equation 2.20, the atmospheric pressure falls off exponentially with height at a rate given by the scale height. Thus, for every 7 km increase in altitude, the pressure drops by about 2/3. At 40 km, the pressure is only a few tenths of a percent of the surface pressure. Similarly, the concentration of molecules is only a few tenths of a percent, and since molecules scatter sunlight, you can see in the picture below that the scattering is much greater near Earth's surface than it is high in the atmosphere.

Quiz 2-2: Harnessing the power of the hydrostatic equation

This quiz will give you practice using the hydrostatic equation to learn interesting and useful properties and quantities of the atmosphere.

- I strongly suggest that you do all your calculations on this quiz using the Excel workbook.

- There is no Practice Quiz 2-2. However, you have extra time to take this quiz.

- When you feel you are ready, take Quiz 2-2 in Canvas. You will be allowed to take this quiz only once. This quiz is timed, so after you start, you will have a limited amount of time to complete it and submit it. Good luck!

2.3 First Law of Thermodynamics

2.3 First Law of Thermodynamics

Weather involves heating and cooling, rising air parcels and falling rain, thunderstorms and snow, freezing and thawing. All of this weather occurs according to the three laws of Thermodynamics. The First Law of Thermodynamics tells us how to account for energy in any molecular system, including the atmosphere. As we will see, the concept of temperature is tightly tied to the concept of energy, namely thermal energy, but they are not the same because there are other forms of energy that can be exchanged with thermal energy, such as mechanical energy or electrical energy. Each air parcel contains molecules that have internal energy, which when thinking about the atmosphere, is just the kinetic energy of the molecules (associated with molecular rotations and, in some cases, vibrations) and the potential energy of the molecules (associated with the attractive and repulsive forces between the molecules). Internal energy does not consider their chemical bonds nor the nuclear energy of the nucleus because these do not change during collisions between air molecules. Doing work on an air parcel involves either expanding it by increasing its volume or contracting it. In the atmosphere, as in any system of molecules, energy is not created or destroyed, but instead, it is conserved. We just need to keep track of where the energy comes from and where it goes.

Let U be an air parcel’s internal energy, Q be the heating rate of that air parcel, and W be the rate that work is done on the air parcel. Then:

The dimensions of energy are M L2 T–2 so the dimensions of this equation are M L2 T–3.

To give more meaning to this energy budget equation, we need to relate U, Q, and W to variables that we can measure. Once we do that, we can put this equation to work. To do this, we resort to the Ideal Gas Law.

For processes like those that occur in the atmosphere, we can relate working, W, to a change in volume because work is force times distance. Imagine a cylinder with a gas in it. The cross-sectional area of the piston is A. If the piston compresses the gas by moving a distance dx, the amount of work being done by the piston on the gas is the force (pA) multiplied by the distance (dx). W is then pAdx/dt. But the volume change is simply –Adx/dt and so:

Reducing a volume of gas (dV/dt < 0) takes energy, so working on an air parcel is positive when the volume is reduced, or dV/dt < 0. Thus:

Heat Capacity

The heat capacity C is the amount of energy needed to raise the temperature of a substance by a certain amount. Thus, and has SI units of J/K. C depends on the substance itself, the mass of the substance, and the conditions under which the energy is added. We will consider two special conditions: constant volume and constant pressure.

Heat Capacity at Constant Volume

Consider a box with rigid walls and thus constant volume: . No work is being done and only internal energy can change due to heating.

The candle supplies energy to the box, so Q > 0 and dU/dt > 0. The internal energy can increase via increases in molecular kinetic and potential energy. However, for an ideal gas, the attractive and repulsive forces between the molecules (and hence the molecular potential energy) can be ignored. Thus, the molecular kinetic energy and, hence, the temperature, must increase:

So,

CV, the constant relating Q to temperature change, is called the heat capacity at constant volume. Heat capacity has units of J K-1.

Remember that is the change in the air parcel’s internal energy.

The heat capacity, CV, depends on the mass and the type of material. So we can write CV as:

where cV is called the specific heat capacity. The adjective “specific” means the amount of something per unit mass. The greater the heat capacity, the smaller the temperature change for a given amount of heating.

Some specific heat capacity values are included in the table below:

| gas | cV (@ 0oC) J kg–1 K–1 |

|---|---|

| dry air | 718 |

| water vapor | 1390 |

| carbon dioxide | 820 |

Solve the following problem on your own. After arriving at your own answer, click on the link to check your work.

Check Your Understanding

Consider a sealed vault with an internal volume of 10 m3 filled with dry air (p = 1013 hPa; T = 273 K). If the vault is being heated at a constant rate from the outside at a rate of 1 kW (1,000 J s–1), how long will it take for the temperature to climb by 30 oC?

The 1st Law can be rewritten as:

However, dV/dt = 0 because the vault’s volume isn’t changing. So, we can use the equation, rearrange it and integrate it:

How do we find the mass of the air inside the vault? Use the Ideal Gas Law to find the number of moles and then multiply by the mass per mole!

Often we do not have a well-defined volume, but instead just an air mass. We can easily measure the air mass’s pressure and temperature, but we cannot easily measure its volume. Often we can figure out the heating rate per volume (or mass) of air. Thus:

where q is the specific heating rate (SI units: J kg–1 s–1).

Heat Capacity Constant Pressure

The atmosphere is not a sealed box and when air is heated it can expand. We can no longer ignore the volume change. On the other hand, as the volume changes, any pressure changes are rapidly damped out, causing the pressure in an air parcel to be roughly constant even as the temperature and volume change. This constant-pressure process is called isobaric.

Now the change in the internal energy could be due to changes in temperature or changes in volume. It turns out that internal energy does not change with changes in volume. It only changes due to changes in temperature. But we already know how changes in internal energy are related to changes in temperature from the example of heating the closed box. That is, the internal energy changes are related by the heat capacity constant volume, Cv. Thus:

Note that when volume is constant, we get the expression of heating a constant volume.

Suppose we pop the lid off the box and now the air parcel is open to the rest of the atmosphere. What happens when we heat the air parcel? How much does the temperature rise?

It’s hard to say because it is possible that the air parcel’s volume can change in addition to the temperature rise. So we might suspect that, for a fixed heating rate Q, the temperature rise in the open box will be less than the temperature rise in the sealed box where the volume is constant because the volume can change as well as the temperature.

Enthalpy

Enthalpy (H) is an energy quantity that accounts not only for internal energy but also the energy associated with working. It is a useful way to take into consideration both ways that energy can change in a collection of molecules – by internal energy changes and by volume changes that result in work being done.

Enthalpy is the total energy of the air parcel including effects of volume changes. We can do some algebra and use the Chain Rule to write the First Law of Thermodynamics in terms of the enthalpy:

If the pressure is constant, which is true for many air parcel processes, then dp/dt = 0 and:

Summary

- In a constant volume process, heating changes only the internal energy, U.

- In a constant pressure process, heating changes enthalpy, H (both internal energy and working).

In analogy with constant volume process, for a constant pressure process, we can write:

where Cp is the heat capacity at constant pressure and cp is the specific heat capacity at constant pressure.

Note that cp takes into account the energy required to increase the volume as well as to increase the internal energy and thus temperature.

What is the difference between cp and cv? You will see the derivation of the relationship, but I will just present the results:

- by mole:

- by mass for dry air:

- by mass for water vapor:

| gas | cV (@ 0oC) J kg–1 K–1 | cp (@ 0oC) J kg–1 K–1 |

|---|---|---|

| dry air | 718 | 1005 |

| water vapor | 1390 | 1858 |

Since cp > cv, the temperature change at constant pressure will be less than the temperature change at constant volume because some of the energy goes to increasing the volume as well as to increasing the temperature.

Summary of Forms of the First Law of Thermodynamics

It is often useful to express these equations in terms of specific quantities, such as specific volume (α ≡ V/m = ρ-1), specific heat at constant pressure (cp ≡ Cp/m), and specific heat at constant volume (cV ≡ CV/m). With these definitions, the first three equations above become:

You can figure out which form to use by following three steps:

- Define the system. (i.e., what is the air parcel and what are its characteristics?)

- Determine the process(es) (i.e., constant pressure, constant volume, heating, cooling?). Choose the form of the equation by making a term with a conserved quantity go away (i.e., dp/dt = 0 or dV/dt = 0) because then you have a simpler equation to deal with.

- Look at which variables you have and then choose the equation that has those variables.

Check Your Understanding

Consider the atmospheric surface layer that is 100 m deep and has an average density of 1.2 kg m–3. The early morning sun heats the surface, which heats the air with a heating rate of F = 50 W m–2. How fast does the temperature in the layer increase? Why is this increase important?

- What is the system? Air layer. Since we know the heating per unit area, work the problem per unit area.

- What is the process? Constant pressure and heating by the sun.

- Which variables do we have?

This temperature increase is important because it is one of the most important factors in determining whether convection will occur later in the day. We will talk more about instability soon.

Here is a video (1:30) explanation of the above problem:

Let's go through this problem considering the heating of air in the lowest part of the atmosphere, which is called the atmospheric boundary. The sun heats the earth, and then the earth heats the air in contact with it. To see how fast the air will heat up, we need to know the heating rate, but we also need to know the air parcel's capacity. Heating rate is given in watts per meter squared, then we can multiply by some arbitrary area to get the total heating rate. Almost always, atmospheric heating and cooling occurs at constant pressure. Heat capacity, then, depends on the specific heat capacity at constant pressure. But it also depends on the air parcel's mass, which is density times volume. So we need to find the density, if it isn't given to us. You can use the ideal gas law for that. The volume is just the height times the area. So we put the heating rate on the left hand side and the effect of the heating on the parcel on the right. We are assuming a fairly uniform air parcel, so we see we really didn't need to multiply by area at all, since it just cancels out. We can rearrange this equation to get the temperature change for time on the left and all the known variables on the right. And then we can put the numbers in, and we can find out what the change in temperature with time is.

Check Your Understanding

Consider the atmospheric surface layer that is 100 m deep and has an average density of 1.2 kg m–3. It is night and dark and the land in contact with the air is cooling at 50 W m–2. If the temperature at the start of the night was 25 oC, what is the temperature 8 hours later?

- What is the system? Air layer. Since we know the cooling per unit area, work the problem per unit area.

- What is the process? Constant pressure and cooling by the land radiating energy to space and the air cooling by being in contact with the land.

- Which variables do we have?

Since the cooling continues for 8 hours, the total amount of cooling is –1.5 K/hr x 8 hr = 12 K or 12 oC. Thus, the temperature 8 hours later will be 13 oC.

This cooling near the surface creates a layer of cold air near the surface with a layer of warmer air above it. The layering of warm air over colder air creates an temperature inversion, which suppresses convection and lock pollutants into the air layer near Earth's surface.

2.4 The higher the temperature, the thicker the layer

2.4 The higher the temperature, the thicker the layer

A surprising way to relate the distance between two pressure surfaces to the temperature of the layer between them.

Consider a column of air between two pressure surfaces. If the mass in the column is conserved, then the column with the greater average temperature will be less dense and occupy more volume and thus be higher in altitude. But the pressure at the top of the column is related to the weight of the air above the column, which is constant, and so the upper pressure surface is higher in altitude. If the temperature of the column is lower, then the pressure surface at the top of the column will be lower in altitude.

We can look at this behavior from the point-of-view of hydrostatic equilibrium.

If the temperature is greater, then the change in p with height is less, which means that any given pressure surface is going to be higher.

The difference between any two pressure surfaces is called the thickness.

We can show that the thickness depends only on temperature:

Integrate both sides:

or

where T is the average temperature of the layer between p1 and p2. So, the thickness is actually a measure of the average temperature in the layer.

To Learn More

As some of you already know, you can use the thickness between different pressure surfaces to estimate the type of precipitation that will fall - snow, rain, or a mixture. You can check out these resources for some more information and example problems:

Check Your Understanding

Suppose that the 500 mb surface is at 560 dam (decameters, 10s of meters) and the 1000 mb surface is at 0 dam. What is the average temperature of the layer between 1000 mb and 500 mb?

Rearrange equation 2.4 to get an expression in terms of the average temperature and then put all the numbers into the equation to find the average temperature of the layer. Make sure that all the units are correct.

2.5 Adiabatic Processes: The Path of Least Resistance

2.5 Adiabatic Processes: The Path of Least Resistance

Adiabatic Process

So far, we have covered constant volume (isochoric) and constant pressure (isobaric) processes. There is a third process that is very important in the atmosphere—the adiabatic process. Adiabatic means no energy exchange between the air parcel and its environment: Q = 0. Note: adiabatic is not the same as isothermal.

Consider the Ideal Gas Law:

If an air parcel rises, the pressure changes, but how does the temperature change? Note that the volume can change as well as the pressure and temperature, and thus, if we specify a pressure change, we cannot find the temperature change unless we know how the volume changed. Without some other equation, we cannot say how much the temperature will rise for a pressure change.

However, we can use the First Law of Thermodynamics to relate changes in temperature to changes in pressure and volume for adiabatic processes.

Derivation of the Poisson Relations

I do not expect you to be able to do this derivation, but you should go through it to make sure that you understand all the steps as a way to continue to improve your math skills. Start with the following specific form of the 1st Law for dry air (Equation 2.41) and then assume an adiabatic process (q = 0):

Divide both sides by T:

where we figured out the two terms were just derivatives of the natural log of T and p.

But d/dt = 0 just means that the value is constant:

Divide by cp:

If the natural log of a variable is constant then the variable itself must be constant:

We can rewrite Rd/cp as a new term denoted by the Greek letter gamma, γ

We can use the Ideal Gas Law to get relations among p, V, and T, called the Poisson’s Relations:

Potential Temperature

The Poisson Relation that we use the most is the relation of pressure and temperature because these are two variables that we can measure easily without having to define a volume of air:

or

We call θ the potential temperature, which is the temperature that an air parcel would have if the air is brought to a pressure of po = 1000 hPa. Potential temperature is one of the most important thermodynamic quantities in meteorology.