Module 2: The Life Cycle of a Mine and Related Matters

Module 2 Overview

Module 2 Overview

We learned a lot… actually, I hope you’ve learned a lot about the importance of minerals and the need for mining in Module 1. We now have a much better understanding of where we mine and why we mine. We have learned about the complexity of conducting a mining operation in a societal context. The study of this has allowed us to gain not only an appreciation for the complexity of operation in today’s world, but it has also given us a reason to learn more about the major stakeholders. We will draw on much of this recently acquired knowledge throughout this course.

So, we know a lot of the importance of minerals in modern society, we better understand how ubiquitous mining is in the national and global economies, and we know about the important stakeholders. Suppose we want to mine one of those 85+ minerals found in economic quantities within the U.S. How do you go about opening and operating a mine? We’ll first address this topic in Lesson 2.1, where we will examine the life cycle of a mine. In Lessons 2.2 and 2.3, we’ll look at the body of laws that apply to particular parts or throughout the life cycle of the mine. Equipped with this knowledge, as well as that of Module 1, we will then devote the remainder of the course to the specific details of surface and underground mining.

Learning Outcomes

At the successful completion of this module, you should be able to:

- describe each of the five stages in the life of a mine;

- explain the difference between an Act (law) and a Regulation;

- explain the purpose of the Code of Federal Regulations, and Title 30, Volume I, Chapter I of the Code of Federal Regulations;

- list and describe the five major categories of mining law that govern everything from access to minerals, how we mine, to how we leave the site when we have finished mining;

- cite specific examples of laws that the mining engineer will encounter within the aforementioned categories;

- describe the differences in the acquisition of rights to prospect, explore, and mine on public and private lands;

- describe the General Mining Law of 1872, and specifically explain:

- the stated purpose of the Law,

- a mining claim, and the difference between a lode and a placer,

- what is meant by locatable minerals, and the types of minerals that qualified under the Law,

- the difference between a patented and unpatented claim;

- explain the motivation behind the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920, and the change that this Act made to the Mining Law of 1872;

- explain the effect of three other major amendments to the Law of 1872, made in 1954, 1955, and 1976;

- explain why the Law of 1872 remains controversial to this day.

What is due for Module 2?

This module will take us two weeks to complete. Please refer to the Course Syllabus for specific time frames and due dates. Specific directions for the assignment below can be found within this lesson.

| Activity | Location | Submitting Your Work |

|---|---|---|

| Read | Pages 26-46 in the course textbook | No Submission |

| Complete |

|

Canvas |

Questions?

Each week an announcement is sent out in which you will have the opportunity to contribute questions about the topics you are learning about in this course. You are encouraged to engage in these discussions. The more we talk about these ideas and share our thoughts, the more we can learn from each other.

Lesson 2.1: Life Cycle of Mines

Lesson 2.1: Life Cycle of Mines

Modern mining occurs over five stages, which constitute the life cycle of a mine. They are listed here and are summarized in the following paragraphs.

- Prospecting

- Exploration

- Development

- Exploitation

- Reclamation

While the principal activities of each stage are distinct, there can be significant overlap in the tasks comprising the stages as well as the professionals active in the stages.

Prospecting

The crust of the Earth is made of rocks and minerals, and many minerals can be found with little difficulty. In general, the challenge is not finding the mineral of interest; but rather finding an economic concentration of the mineral. Despite the fact that minerals are everywhere, it is a rarity to find most of them in sufficient concentration to justify the cost of developing a mine and extracting the mineral of interest. In most instances, prospecting is about finding geologic anomalies! The professionals that lead this first stage of the life cycle are geoscientists, e.g., geologists, geochemists, and geophysicists.

Geologists often narrow their search by taking advantage of accumulated knowledge, which may be public or proprietary, to narrow the geographic scope of their search. They may use satellite images or aerial mapping techniques as they search for promising indicators. Then the search will continue with on-the-ground investigation using surface-mapping, structural analysis, and other scientific techniques. In many cases, the expertise of geochemists and geophysicists may be required to help in the discovery of an orebody, i.e., a potentially economic concentration of the target mineral(s). Geochemists may glean vital clues by analyzing water or soil samples, for example; and geophysicists may use instruments to detect subtle and localized changes in the electrical or magnetic field, or they may map rock layers deep under the surface using seismic methods.

The goal of this team of geoscientists, and indeed the goal of prospecting, is to discover a concentration of the target mineral that has the potential to be mined at a profit. What do you think determines if it has the potential to be mined at a profit?

While there are many factors that will be considered, there are only a few that are germane at this stage. Those few would include the size and grade of the orebody. If the outcome of the prospecting stage is evidence supporting the presence of an orebody of sufficient size and grade to justify mining, then work will begin on the second stage, known as exploration. The prospecting stage may have cost tens of thousands to millions of dollars. The next stage may be even more expensive, and is only undertaken if there is sufficient evidence to suggest an economic deposit of the target mineral(s).

Exploration

The next stage, exploration, will involve mining engineers as well as geoscientists who were involved in the prospecting stage. The goal of exploration is to define more exactly the size of the orebody, the grade, and the spatial and geotechnical characteristics of the deposit and surrounding rock. I think it is useful to think about exploration as a problem in risk management.

What is the risk that we need to manage? Simply, the risk is that we would spend millions of dollars to develop a mine, only to find that we can’t mine the deposit economically. How could we find ourselves in such a job-ending predicament? Perhaps the size of the deposit is far less than we estimated, or the grade is much poorer than we believed, or maybe there are large areas where the ore disappears or where there are intrusions of unwanted material, or features that make it difficult to extract, and so on. You get the idea – you need to be a good risk manager!

If you are the one to make the decision, to go forward or abandon the project, what can you do to manage your risk? You can seek to obtain as much information as possible about the deposit, although information acquisition comes at a price. It costs money to conduct more studies to learn more about the deposit. How much are you willing to spend? How badly do you want that information? Well, that depends on how much risk you are willing to accept. Hence, the concept of, and need for, risk management. As we continue through this lesson and this course, you will begin to develop a sense for managing the risk associated with these projects.

Our first significant encounter with risk management is in the exploration stage, and our first interest will be to estimate the size of the reserve, i.e., how many tons exist that can be recovered, and the quality of the reserve, i.e., what percentage of the recoverable tons contain the target mineral(s). This first task is known as reserve estimation, and consists of two parts: estimating the quantity and quality of the orebody; and determining how much of that orebody can be recovered utilizing currently available mining practices. Estimating the quantity and quality of the resource requires sampling, usually by drilling, and then analyzing the sampled material. Generally, the more samples that we take, the more certain we can be in our estimates of the quantity and quality of the resource. In other words, the more we sample, the more we reduce the risk of bad outcome. And of course, it costs money to acquire each sample!

However, it is not only about the quantity and quality of the resource. We could have a resource of high quality and enormous size. But that alone is insufficient. We have to be able to extract this resource economically from the earth. This is not always doable, or more likely, it is doable for some but not all of the resource. The technical reasons for this are varied, but during the exploration phase, the team will be interested in far more than simply the size of the resource. They will employ methods to estimate the strength of the rock surrounding the orebody as well as the strength of the ore itself. They will look for geological discontinuities and other features that will affect the extraction of the ore. Investors in an expensive mining project are far more interested in how much ore can be mined, processed, and sold, than how much ore is in the ground! We’ll look at this in more detail in Module 3 when we talk about resource and reserve estimation.

There is one of two likely outcomes from the exploration stage: a decision to continue development on a project that appears promising or a decision to abandon the project. If the decision is to move forward with the project, then work will advance to the development stage.

Development

Essentially, the development stage includes all of the activities necessary to prepare for extraction of the ore. These activities begin with the engineering studies that immediately follow the exploration stage through the construction of the physical plant to access and process the ore. In the case of a surface mine, the development work to access the orebody may consist of removing vegetation and the overburden, which covers the orebody; whereas in the case of an underground mine, the development work will conclude with the construction of the shaft or other means of connecting the surface with the orebody that is located some distance beneath the surface.

A significant amount of capital must be available to open a mine. In many cases, this money must be raised from investors, and in some cases the company will have the capital to invest in the project. In either case, additional engineering studies will be conducted to establish the feasibility of opening a mine. A company with its own capital, will have many competing projects for that money, and they will want to allocate it to the project that best meets their criteria for a return on their capital. Investors on the other hand, will also want to understand the income potential of their investment. And in either scenario, both will want to understand the risks associated with the project. In Module 4 we will look at the engineering studies that are performed to address these concerns. For now, you should be aware that a prefeasibility study is nearly always conducted as the first task in this stage; and that the requirements for conducting and reporting on this prefeasibility study are prescribed by legal documents and are regulated by various government agencies around the globe. It is a requirement that these studies, completed according to the applicable standard, be published as part of an effort to raise funds for the project on any of the stock exchanges.

The selection of the mining method will be made during the prefeasibility study, as this is an essential consideration when determining how much of the in-place resource can be extracted. The selection is based on an evaluation of several factors that we will examine in Module 4; often the choice of a method will be guided by the practices found in other mines in the region that are mining some of the same commodities.

The prefeasibility study will determine in most cases whether or not a viable project exists. If so, the development work will continue. Rights to the land and the deposit will be acquired, detailed engineering studies will be completed, bid packages will be prepared, and construction will begin on surface facilities, such as offices and labs, warehouses, shops, and the mineral processing plant, among others. Land clearing and other surface infrastructure construction, including roads, electric power, water, and so on will be ongoing during the development stage. As described previously, the development stage is largely completed with those tasks that allow direct access to the orebody. Once the orebody has been made accessible, the extraction process can begin.

Exploitation

One definition of this word, according to the dictionary, is the process of making the fullest and most profitable use of a natural resource. Indeed, the process of extracting the ore from the surrounding rock and processing it to make the valuable components available to society is the goal of the exploitation stage. Essentially, this stage consists of the extraction activities, in which we remove the ore and move it to a plant for the beneficiation activities, in which we separate and concentrate the valuable minerals from the run-of-mine materials coming from the mine and going into the mineral processing (beneficiation) plant. An important concern is the handling and disposal of these tailings, which remain after the valuable components have been removed. We will say little about the mineral processing other than these two points: the design and operation of mineral processing is beyond the scope of this course; and the mining engineer, in the selection and use of a particular mining method, along with the associated unit operations, can impact significantly the cost of the mineral processing operation. We will concern ourselves with the latter point, when we talk about the selection of the mining method and some of the unit operations.

The mining method will have been chosen well before exploitation begins, although the method may be altered or occasionally changed if conditions change significantly. Over time, the equipment and practices may be changed to achieve economic, environmental, or safety goals. After all, many mines will be in the exploitation stage for several decades, and during this time the available mining technology and state-of-the-art practices will certainly change, even if mining conditions at the mine have not changed significantly from the day that the mine was opened. It is not unusual to find mines that began as surface mines, and then after the resource could no longer be recovered economically by surface mining, an underground mine was developed.

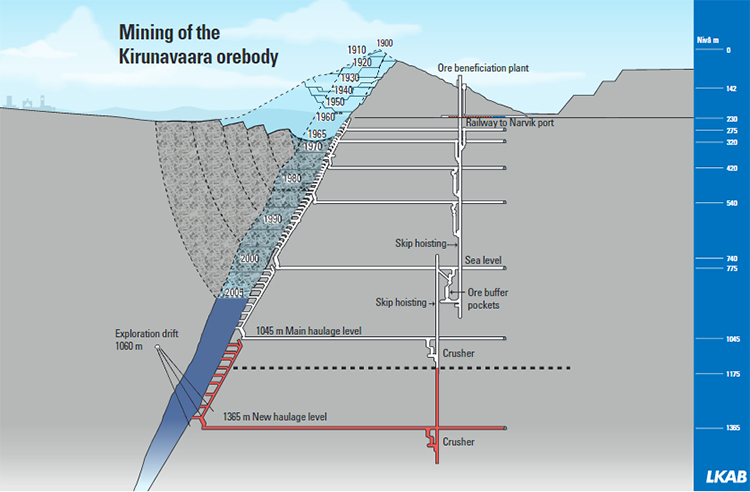

Mining of the Kirunavaara iron orebody in Kiruna, Sweden is a famous example of this, and as you will note in the Figure 2.1.1, below, that mining began in 1900 as a surface mining operation, and continued as such for 65 years. At that point in time, the cost of removing the overburden to access the ore became greater than the value of the ore that was being uncovered. This is known as the breakeven stripping ratio, and when this ultimate pit limit has been reached, mining will stop or alternatively, an underground mine will be developed; and that is what happened at this mine. Nearly 125 years after the initial mining, the mine still has many years of life remaining.

Whether it is in five, fifty, or five-hundred years, the exploitation stage will come to an end. The orebody for which the company has the rights to mine may have been exhausted, it may be uneconomical to continue mining, or the perhaps the market for the commodity no longer exists. Regardless of the cause, at the conclusion of active mining, the company cannot simply “walk away” from the operation; although well into the beginning of the 20th century that was the common practice. That irresponsible practice has left us with a legacy of abandoned mines, numbering in the thousands. Even though most of these were very small operations, some were large, and regardless of their size, many of them present public safety and environmental hazards. There may be, for example, shafts that hikers could unwittingly fall into, pollutants draining from old workings, or unsightly piles of tailings. This is a serious issue for society, and it is a major reason why mining has a negative public image.

The conclusion of active mining signals the beginning of the fifth and final stage in the mine’s life cycle, known as reclamation.

Reclamation

The goal of this final stage is to return the mine site to its original condition. In the case of an underground mine, we can do that rather completely. In the case of a surface mine, we cannot in many cases return it to original condition because so much material will have been removed and sold. However, we can take steps to ensure that the area is reclaimed to be free of safety and environmental hazards in all cases, and that the end result is aesthetically pleasing in many cases. The latter is simply impossible in the case of large open pit mines, as the volume of material removed over the years is so large that the remaining pit dimensions cannot be covered over. The number of these operations is a very small fraction of all surface mines, and the majority of these are located in rather remote and rugged areas. However, to be clear, even in those cases, the obligation to leave an area free of safety and environmental hazards is unchanged.

Overall, and during the reclamation stage, it will be necessary to remove completely all of the surface physical plant, e.g., buildings, power lines, and so on. Returning the land to original contours and/or ensuring that options for land use after mining are as good or better than the use prior to mining is important. This work may include grading and revegetation, among other steps. In most cases, the final outcome of the reclamation stage is a site on which the land is once again available for public or private use, free of hazards, and often more attractive and useful than prior to mining.

Of course, it is not just left to the social conscience of the company to ensure that reclamation is completed: there are laws, regulations, and multiple government agencies to ensure that the reclamation is completed. In fact, you will have to prepare and submit your plan for reclamation before you have started mining. And, in virtually all cases, you will have to put up a bond to ensure that the reclamation can be completed, even if you go out of business before the site has been fully reclaimed. These bonds are funded at a level to ensure that the work can be completed if the company defaults on its obligation. The cost of bonds can run into the millions of dollars very quickly, and the money is not returned to the company until the work covered by that bond is completed and approved by the government agency. In some cases, a company may need to operate a water treatment plant in perpetuity to ensure, for example, that groundwater drainage from an abandoned underground mine does not pollute the local streams. In such a case, the company will be required to post a bond of sufficient value that the government could continue to operate the plant if the company should go out of business.

Such planning and actions are consistent with the 21st century goal of sustainability. Whether we’re meeting humankind’s need for food or minerals, for example, we have a societal obligation to do so in a sustainable manner. This is generally accepted to mean that in meeting our current needs, we will use practices that will not compromise future generations’ ability to meet their needs. Further, it is implied that these practices will not compromise the environment nor the health of future generations. Sustainable practices are based on recognition that resources are finite. Consequently, we design mines to maximize the extraction ratio so that we can meet our production goals while disturbing as little of the resource as possible. In contrast, years ago, some mines might only recover less than half of the in-place reserve, but in the process, they would “sterilize” the remaining resource, i.e., the remaining resource could not be safely recovered in the future because of the way that the previous mining was conducted.

The five stages of a mine’s life cycle as presented in this lesson are a convenient way to describe the sequence of activities that define a modern mining operation. As you have no doubt realized, the boundary between each stage is not as crisp as this lesson might have implied. Not only is there overlap, but also at different times and in different places, parts of the cycle may repeat. For example, as the exploitation of a deep metal mine continues, new exploration activities will be initiated, but not from the surface. Instead, they will be conducted deep within the mine, where the geologists have a “front row seat” to observe and characterize the orebody in greater detail.

In the next lesson, we’ll look at the body of laws that apply to these stages of mining.

Test your knowledge!

Lesson 2.2: Mining Law

Lesson 2.2: Mining Law

The body of law governing access to minerals, the rights to mine, and the conditions under which mining is conducted and concluded is vast. Some laws apply primarily to the earliest part of the cycle, i.e., prospecting and exploration, whereas others are more relevant to the end stage of the cycle, i.e., reclamation. The majority will apply through all stages. In total, the number of laws that impact a mining operation number in the hundreds, and fortunately there are many lawyers who choose to specialize and practice in mining law! Still, there are some laws that directly impact the work of the engineers and scientists who are working in the various stages of the mine’s life cycle; and further, some of these laws are very technical in nature, and the mining engineer and other professionals will require sufficient knowledge of them to complete their work. Accordingly, a goal of this lesson is to build a foundation of knowledge for your future work.

Laws can be national (federal) or regional (state or local) in origin. Certain aspects of a mining operation could be subject to international agreement, as well; although this topic is beyond the scope of this lesson. It should be noted that the multinational mining companies typically adhere to the most rigorous set of laws and standardize their operations to be in compliance with those. The “home” country of the multinational may have laws that govern the activity of the corporation, even when those activities are in another country. Again, this is a topic well beyond the scope of this course.

It is important to remember the laws and regulations are not the same, even though in many cases the outcome is indistinguishable. Congress or committees of Congress, develop bills, and upon passage by both the Senate and the House of Representatives, the act, as it is then known, goes to the President for signature. If the president signs the bill, it becomes law. The law may have specific provisions with which the mining company must comply, or face civil or criminal proceedings. Often the law also directs an administrative agency, such as MSHA or the EPA, to develop regulations that will accomplish Congress’ intent in passing the legislation. The agency will write specific and often very prescriptive regulations. The mine operators are then legally bound to comply with those regulations, or face a range of civil or possibly criminal actions. Typically, a violation of mandatory regulation results in a fine of tens of dollars up to hundreds-of-thousands of dollars depending on defined criteria, which include the severity of the violation. It can also result in a closure of the mine until the violation is corrected, and in a few cases, criminal charges may be pressed.

Here is an example of an Act. If you note the last sentence on the page, you'll see the language directing the agencies to develop and promulgate regulations.

FEDERAL MINE SAFETY AND HEALTH ACT OF 1977

[Public Law 91–173]

[As Amended Through P.L. 109–280, Enacted August 17, 2006]

AN ACT To provide for the protection of the health and safety of persons working in the coal mining industry of the United States, and for other purposes.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled,

That this Act may be cited as the “Federal Mine Safety and Health Act of 1977”.

(30 U.S.C. 801 nt) Enacted December30,1969, P.L, 91–173,sec.1,83 Stat. 742; amended November 9, 1977, P.L. 95–164, title I, sec. 101, 91 Stat. 1290.

FINDINGS AND PURPOSE

SEC. 2. Congress declares that—

(a) the first priority and concern of all in the coal or other mining industry must be the health and safety of its most precious resource -- the miner;

(b) deaths and serious injuries from unsafe and unhealthful conditions and practices in the coal or other mines cause grief and suffering to the miners and to their families;

(c) there is an urgent need to provide more effective means and measures for improving the working conditions and practices in the Nation’s coal or other mines in order to prevent death and serious physical harm, and in order to prevent occupational diseases originating in such mines;

(d) the existence of unsafe and unhealthful conditions and practices in the Nation’s coal or other mines is a serious impediment to the future growth of the coal or other mining industry and cannot be tolerated;

(e) the operators of such mines with the assistance of the miners have the primary responsibility to prevent the existence of such conditions and practices in such mines;

(f) the disruption of production and the loss of income to operators and miners as a result of coal or other mine accidents or occupationally caused diseases unduly impedes and burdens commerce; and

(g) it is the purpose of this Act (1) to establish interim mandatory health and safety standards and to direct the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare1and the Secretary of Labor to develop and promulgate improved mandatory

1References in this Act to the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare are deemed to refer to the Secretary of Health and Human Services pursuant to section 509(b) of the Department of Education Organization Act (20 U.S.C. 3508(b); 93 Stat. 695).

The regulations developed by an administrative agency are compiled in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), which consists of 50 Titles. The list of Titles can be found on the website of the U.S. Government Publishing Office or other sites including Wikipedia. For completeness, we can note that laws are codified in the United States Code (USC), which is also organized by Titles.

Regulations relating to mineral resources are found in Title 30 “Mineral Resources” and many of the regulations affecting the environment are found in Title 40 “Protection of Environment.” Looking more closely at Title 30, you will see that it is divided into volumes, chapters, and parts. Within Title 30, the most applicable content for us is found in Chapter I, which contains the regulations on mine safety and health promulgated by the MSHA. You can download a pdf file of any of these Titles, and I recommend that you download Title 30 Volume 1.

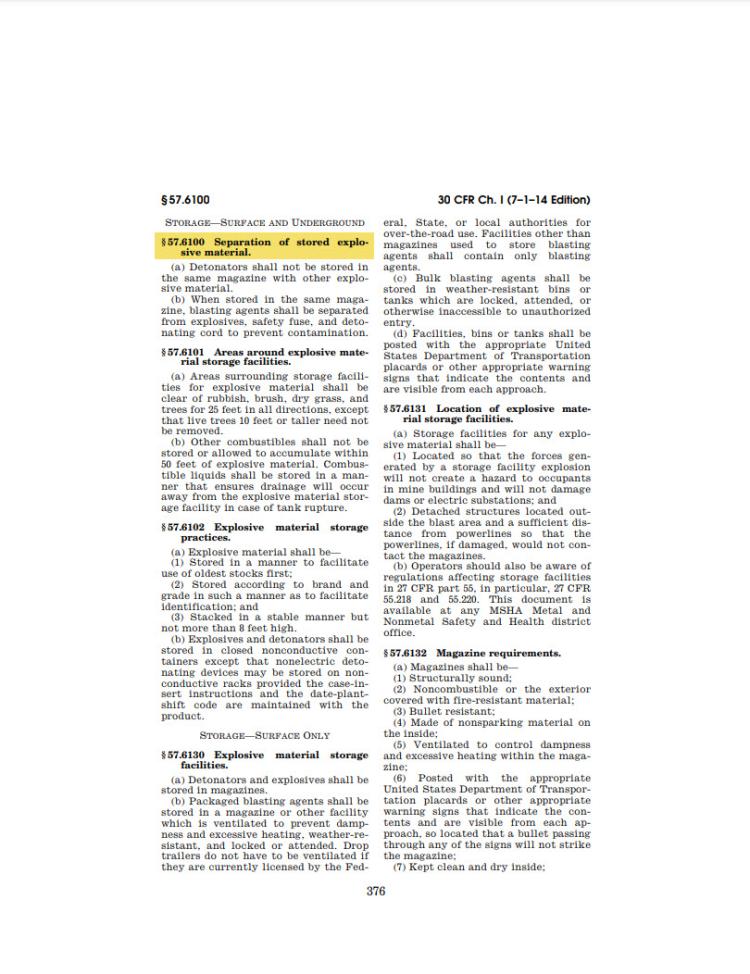

Here is an example from Title 30 to illustrate specific regulations.

If we wanted to cite a specific regulation, for example the one on the separation of stored explosive material, we would write it 30CFR 57.6100.

The regulatory environment has become so complex and pervasive, that even entry-level engineers and scientists will be drawn into conversations regarding requirements of the Mine Act (a law) and regulations. Consequently, it is helpful to understand these terms and where you can go to read them.

With the distinction between laws and regulations behind us, let’s return to our overview of mining law.

First, we can categorize the body of law into five groups for our purposes, as follows:

- access to the land, including the right to mine

- taxes, leasing fees, royalties

- employment, work conditions, and compensation

- environmental protection

- cultural and social issues

Let’s examine each of these in more detail.

Access to the Land, including the Right to Mine

We need access to the land to conduct prospecting and exploration activities, and if we decide to mine, we will need to obtain permission to extract the commodity. Acquisition of these rights is obtained differently on private versus public land. I think we all have an understanding of private land, i.e., land owned by an individual or legal entity such as a company or a trust. Rights to access and mine private property are conveyed simply by an agreement, such as a contract, a lease, or a deed.

What about public land?

All land that was part of the original 13 colonies that became the United States was privately owned. After the birth of the Nation, the U.S. government acquired blocks of land, and that land belonged to the government, i.e., the “public.” Over the years and through different programs, some of that land became privately owned, although vast tracts of public land still exist to this day. In the American West, the government owns nearly half of the land; and in Nevada, for example, the U.S. government owns about 80%. In total, the government owns a third of America! Thus, acquisition of the rights to prospect, explore, and mine on public lands must be completed in compliance with the applicable laws.

The Mining Law of 1872, as amended, governs access to public land for the purpose of prospecting, exploration, and mining. The Bureau of Land Management administers this law within the Department of the Interior. Due to its importance, we are going to discuss this law as a separate topic later in this lesson.

Before moving on to the next category of mining law, I want to make a few more comments regarding the rights acquired on private land. There are many rights that may or may not be transferred in the agreement. For example, if you acquire the right to mine a salt deposit deep below the surface of the Earth, are you entitled to cut and sell the timber on the surface above your underground mine? Likely the answer is: only if you acquired the timber rights as well. What about surface rights above your mine? Can you build a warehouse, shop, or mineral processing plant on the surface? Likely, the answer is: only if you acquired the surface rights for that tract of land. What about the mineral rights themselves? Did you, through your agreement with the private owner acquire the right to mine all minerals or only one?

Suppose that you have obtained the right to surface mine coal. In the process of removing the overlying materials to access the coal bed, you encounter a bed of limestone, for which there is a strong local market. Can you remove the limestone to access the coal? Absolutely. Can you sell the limestone? Maybe not! It depends on how the deed or contract transferred the mineral rights. Let’s look at one last example, which has been the subject of litigation over the years.

You’ve acquired the right to deep (underground) mine a coal seam. The coal has several hundred cubic feet of methane adsorbed for each ton of in-place coal. Modern mining practice would be to “drain” much of this gas prior to mining to lessen the likelihood of a gas explosion during mining. Can you vent the gas to the atmosphere as part of your pre-mining of the seam? Yes. Can you capture and sell the gas? Again, only if you also acquired the rights to the gas!

Over the years, landowners may have sold off some or all of their mineral rights. A company looking at their future interests may go into an area and buy-up the rights to particular minerals. Subsequently, when the landowner sells the land, the deed may exclude certain commodities. Oil and gas rights are commonly split off from the other mineral rights.

Thus, in the acquisition of rights on private land, it is important to know fully which mineral rights are being acquired, e.g. all those to a certain depth, all minerals, or only named minerals; and whether or not the landowner still owns the specific rights that are the subject of the acquisition.

Taxes, Bonds, Leasing Fees, and Royalties

There are several applicable laws and it's well beyond the mining engineer’s responsibility to know and apply them. Notwithstanding, it is important to be aware that the resulting costs are significant, and the mining engineer will include these in feasibility studies. For example, the following costs must be computed and included in analysis of feasibility, i.e., whether or not an economic mining operation can be developed:

- Federal, state, local income taxes, and severance taxes

- Royalties and leasing fees – upfront or as incurred, or both

- Depletion allowance

- Bonds

Typically, the engineering team estimates these values during the feasibility phase of project development. Once the mine is operational, the calculation of these, among others, will be turned over to the accountants and lawyers.

Employment, work conditions, compensation

There are a few hundred applicable laws ranging from Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) to the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) to the Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA), and most are beyond the scope of the mining engineer’s core activities. The mining company will typically have a human resources specialist or department, and will have standard operating policies to ensure that you do not run afoul of the law in your hiring, firing, and management of employees. If your mine site is unionized or there is interest in organizing, you will need to become knowledgeable on the current labor contract, or certain allowed and disallowed practices related to organizing activities. Workplace safety and health is treated as a condition of employment, and primarily this aligns with the Mine Act and MSHA regulations. These will affect significantly your mine design, planning, and operation.

Environmental Protection

There are many laws and resulting federal regulations to protect the environment. As with other categories of mining law, you as an engineer or scientist will not be practicing law in these areas, but you will be required to conduct engineering and scientific studies required by some of these laws, and you will need to be familiar with the compliance responsibilities in the mine design, operation, and closure phases. Here is a short list of laws that you are likely to encounter:

- Clean Air Act

- Clean Water Act

- Solid Waste Disposal Act

- Endangered Species Act

You may think of power plant or perhaps stack emissions, such as from a copper smelter when you hear about the Clean Air Act. And, you would be correct. What about the dust generated when a haul truck drives on a road within the surface mine, or what about the dust that the wind picks-up from storage pile of stone? These are examples of fugitive dust, and there are strict regulations governing these.

The Clean Water Act addresses not only such major pollutants as fertilizer runoff from agricultural activities, but virtually any other potential source. You will be required for example to prepare a storm water discharge management plan to address any water that may run off of your property during a rainstorm and which may have sediment or any contaminant from your operation. Regulations from the same Act will require you to sample water discharges and install and maintain engineering controls to comply with the law.

The waste rock and minerals remaining after the ore has been processed to extract the valuable components are known as tailings. In some cases there may be few tailings, but in many cases, the tailings can account for 90% or more of the run-of-mine material that went into the plant. The Solid Waste Disposal Act will dictate not only the handling of municipal garbage, but also the handling of your tailings.

The Endangered Species Act aims to protect wildlife and their habitat, as well as to develop and administer plans to restore healthy populations of endangered species. Mine planning and operations must develop and execute plans to protect any endangered species that may be within their mine limit. Typically, this affects surface mines or the surface areas of underground mines. As an example, there may be a bird on the endangered species list that nests within the permit area of the mine. You would be required to propose and implement approved measures to ensure that ability of this bird to nest on your property would not be compromised to the detriment of the species. Depending on the area in which you intend to mine, the complexities could require that you retain a zoologist and perhaps other professionals to assist in preparing a plan to comply with the Endangered Species Act.

Sometimes needed and well-intended laws, like this Act, can be twisted for other purposes. I ran into a situation several years ago in which a citizens group was attempting to block a company from obtaining a permit to develop a surface mine, and their stated objection for blocking the permit was that a unique specie, found nowhere else, lived on the site; and that the mining activity would destroy that specie. The specie in question was a spider, and for some spiders, untold generations will live and die within an area of a few square meters. And over time, they will become genetically distinct – distinctions that require rigorous genetic study to identify. Ultimately it was determined that this spider did not qualify under the Act, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Commission signed off on the permit, but not without considerable delay to the project!

The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 created the federal agency, Office of Surface Mining, Reclamation, and Enforcement (OSMRE) with a mandate to enforce reclamation activities at active coal mines, to operate a trust fund to reclaim abandoned mine lands. If you are operating a surface coal mine for example, you will have paid a bond to OSMRE, and your reclamation activities will be inspected to ensure they are consistent with the reclamation plan that you prepared for them. Commonly, the agency is referred to as OSM rather than the complete OSMRE.

Cultural and Social Issues

Two Acts of note in this category are the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 and the Native American Graves Protection Act of 1990. Both are intended to protect and preserve historical and archeological sites. If there are any older structures on a proposed mine site, or if there is any suspicion that there could be items of archeological or cultural significance, a study will have to be completed; and if there are any, the structures, land, or items will have to be preserved. Often it is alleged that the proposed mining site falls under the protection of the aforementioned Acts. Typically, you would hire a consulting firm specializing in historical and cultural evaluation, and they would assign archaeologists to the project.

This concludes our overview of mining law as it intersects with the work of engineers on a mining project. In the next section, we’ll take a more detailed look at the General Mining Law of 1872 as amended.

Lesson 2.3: The General Mining Law of 1872 (as amended)

Lesson 2.3: The General Mining Law of 1872 (as amended)

We discussed the categories of laws that affect mining in the last lesson and took note of important examples of laws within those categories. Engineers working in the mining industry will often need a working knowledge of a few of these laws, particularly those related to mine safety & health, and the environment. The Mining Law of 1872, which is the subject of this lesson, applies primarily to the earliest stages of mining – obtaining the rights to prospect on public lands and then obtaining the rights to mine. It is considered a mandatory topic for mining engineers, and it is not unusual for a question on the P.E. exam to focus on this topic. It may surprise you to learn that the Law, as amended, is relevant today and quite controversial!

The General Mining Law of 1872 authorizes and governs the prospecting and mining for economic minerals on federal public lands, and the U. S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) is the federal agency responsible for administering the Law.

The law has a rich and somewhat convoluted origin, having evolved from earlier legislation that was more about paying off war debts (Civil War) than fostering mineral development. All that aside, the Law was designed to codify orderly processes for acquiring and protecting mineral claims. The primary goal was to address the chaos and violence that was occurring in the mines and mining camps, particularly in Nevada and California. Prospectors and miners would fight over who had the rights to work a parcel of land. Miners from two different camps would be deep underground following a vein of gold, for example, when suddenly their underground workings would intersect. A dispute would quickly arise over who had the right to mine this vein, and such disputes were settled with guns, not lawyers! Thus, the primary goal of this federal law was to establish a set of uniform procedures to address these ambiguities.

A second unstated but likely goal was to promote settlement of the new lands in the West. As you will see, the Law gave options for outright ownership of land.

Over the years, there have been a few important amendments to the Law, and we’ll discuss those, but let’s start with the provisions of the original law first.

The salient elements of the Law are as follows.

All U. S. citizens 18 years of age or older have the right to locate a lode or placer claim on federal public lands that are open to mineral entry.

What does this mean?

- The first and last parts are easy: you have to be a U. S. citizen of a certain age to participate, and it applies only to federal public lands that are open to mineral entry. We know which lands are considered federal public lands from Lesson 2.2. A qualification that we didn’t make then, but need to make now, is that not all public land is open to mineral activity, i.e. mineral activity is prohibited on some federal public lands such as military bases and national parks. Ok, but what about the middle part –a lode or placer claim?

- At the time this law was written, there were two recognized types of mineral deposits: a lode, which is a hard rock vein, e. g. gold or silver; and a placer, which is a gold or silver-bearing sand or gravel, often in the form of a streambed.

The centerpiece of the law is the claim.

A mining claim is the right to explore for and extract minerals from a tract of land. The Law set the maximum size of a lode claim at 600 feet x 1500 feet, and the maximum size of a placer claim to be 20 acres. The Law also established a tunnel site, and this gave the holder rights to any lode found within 3000 feet of the entrance to the tunnel. Finally, the Law established mill sites, which cannot be on mineralized land, must be used for mineral processing, and can be up to 5 acres in size. There are a few other nuances and qualifiers to this, but the key points for you are to know are the definitions of claim, lode, and placer. There is no reason for you to remember the exact sizes of these claims.

The Law defined locatable minerals, i. e. the types of minerals that could be claimed under the law: gold, silver, cinnabar, copper, and other valuable deposits. The named minerals reflected the ones of note at the time the Law was written but also allowed for other valuable commodities to be claimed.

Extra-lateral rights allowed the owner of a claim with an outcrop to follow and mine that vein to wherever it led, including underneath other claims. This provision was also known as the law of the apex.

These mineral veins would often intersect the surface of the land, i.e. there would be an outcrop. It is likely that the vein would dip and go underground, and would continue for a considerable distance. This provision gives guidance on who has the right to mine the vein.

Claim staking is the required procedure of marking the boundaries of the claim and recording it; hence the expression “to stake a claim. ” The exact procedures for staking the claim may vary slightly from state to state.

All mining claims are initially unpatented claims and only give the right to explore and mine. These rights exist for as long as active work is underway each year. If active work ceases, the claim is dissolved and the land reverts back to the public domain. The Law defines active work on an annual basis as: at least $100 of labor shall be expended or $100 of improvements shall be made.

The Law defined a process by which the owner of a claim could patent the claim. Patents are deeds from the federal government for the claim. The holder of an unpatented claim can apply for a “patent” by making an application and paying $5 per acre for a lode claim or $2. 50 for a placer claim.

The owner of a patented claim can put the land to any legal use, and there is no requirement for active work on a patented claim. In other words, once the claim holder has a patent on the claim, the land can be used for farming, for building a house or a hotel, and so on. Literally, the land is owned (deeded) and can be used for any legal purpose! In more recent times, this provision of the Law has become controversial, but we’ll discuss that later.

The General Mining Law of 1872 worked well into the beginning of the 20th century when the Law effectively enabled a major oil rush in the West. You’ll recall that oil and natural gas are considered minerals, and they met the criteria of “other valuable minerals” under the Law. Tracts of land were being gobbled up so quickly that by 1909, President Taft intervened by executive order, withdrawing over three million acres of public lands. Ultimately, Congress crafted a permanent solution in the form of the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920.

This Act explicitly excluded certain minerals as “locatable” under the 1872 Law and required that the rights to these excluded minerals be obtained only by leasing. The minerals that can only be accessed through a lease are oil, natural gas, and other hydrocarbons, coal, phosphate, potassium, sodium, and sulfur.

The Mineral Leasing Act of 1920 and an amendment in 1947 specified the details of the leasing program, including the number of acres that can be leased, payments to the government, the lease period, and bidding procedures. These parameters are different for different minerals. The lease periods are typically 10 or 20 years, and there are provisions for renewals of 10 or 20 years. The payments to the government consist of three components:

- Bonus, which is paid upon award of the lease, and the normally the lease is awarded to the bidder who will pay the largest bonus;

- Rental, which is an annual charge of typically a few dollars per acre; and

- Royalty, which is a percentage of the gross value of the commodity, typically on the order of 10%.

Over the 30 years, there have been no less than 35 amendments to the Mineral Leasing Act, but the substantive points outlined here remain unchanged. Amendments and attempted amendments to this Act are ongoing for a couple of reasons. First, the revenue from the leases into the U. S. Treasury is significant, and mineral leases are an attractive target for legislators looking for new sources of revenue to fund spending on their projects; and tinkering with the leasing process can facilitate or impede mining activity on federal lands. Certain pro-mining changes to the lease parameters for potassium, for example, could result in an increase in potash mining; whereas increases in lease costs or restricted bidding for coal leases could reduce coal mining on federal lands, which might serve the interests of those opposed to fossil fuel production. Notwithstanding, the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920 as amended, generates significant revenue for the federal government, and provides a reasonable climate for mining companies to produce minerals in a competitive marketplace.

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) is the federal agency with the primary responsibility to operate the leasing program.

There are three other amendments to the general Mining Law of 1872 that deserve mention here. An amendment in 1954 provided for multiple minerals to be extracted from a claim, and another in 1955 withdrew the common minerals of sand, gravel, and cinders from the list of locatable minerals. Finally, in 1976 the Federal Land Management Act was passed, with a primary purpose of reducing the destruction of the land surface of mining claims by requiring reclamation permits, and federally approved plans before the surface could be disturbed. It also strengthened claim recording and abandonment procedures.

The General Mining Law of 1872 as amended enables individuals or companies to obtain the rights to prospect and mine on federal public lands. The 1920 amendment removed certain minerals from the list of locatable minerals under the Law, and established a leasing program for access to the specific minerals covered under this Mineral Leasing Act of 1920. Although this Act has been tweaked over the years with amendments, the current leasing programs administered by the BLM are relatively unchanged. The 1976 amendment, the Federal Land Management Act established the first environmental protection for the surface of land tracts acquired on federal public lands, by requiring reclamation permits and approved plans prior to the initiation of any mining activity.

Finally, I want to close this lesson by calling your attention to an important change that occurred in 1994 –a change that occurred not to the law via an amendment, but rather a change enforced by a congressional budget action.

Unforeseen or changing circumstances led to abuses or unintended and undesirable consequences of the 1872 Law. For example, the oil rush was noted as the main cause of the 1920 amendment. It became increasingly evident in the 1980s and early 1990s that some entities were acquiring large tracts of valuable real estate by filing claims, patenting those claims, and then using the land for real estate development and other commercial but non-mining activities. Remember that once a claim is patented, the holder owns the land and can use it for any legal purpose. It is said, for example, that much valuable real estate around Las Vegas was acquired for the few dollars required to obtain a patent. Clearly, this is an abuse of the Law’s intent.

Congress wanted to eliminate this practice, but there was no agreement to the content of a new amendment. Instead, they used a procedural tactic to accomplish their goal of eliminating the abuse, without writing an amendment. They added language to the appropriation bill for the Department of the Interior that prohibits the use of appropriated funds by the BLM to process and award claim patents! As a result of this, BLM has been unable to award a single claim patent since 1994, and will not be able to do so, until Congress removes that budget restriction! This tactic is used from time-to-time, and there are other mining examples. Consequently, it is worth spending a few minutes to explain this tactic in a bit more detail.

It is often said that Congress controls the purse strings, i.e. Congress appropriates the funds for the administrative agencies in the Executive Branch of the government. If Congress likes something that an agency is doing or proposing to do, it can “reward” the agency by appropriating more money for their budget. On the other hand, if Congress disapproves of an agencies behavior in some regard, it can reduce that agency's budget. Congress can even prohibit an agency from using the money in their budget, i.e. the funds that Congress appropriated, for a specific purpose. Since the employees of the agency are paid with appropriated funds they could not legally do whatever Congress is prohibiting. It’s a very effective tool! So, in the budget for fiscal year 1994, Congress added the language that effectively stopped the abuse by preventing the issuing of patents under the 1872 law. This appropriations language has been included in every budget since 1994.

The General Mining Law of 1872 as amended has been controversial at different times, and as described previously, there were unforeseen consequences or even abuses; and in the end, Congress dealt with them by amending the Act or more recently by exercising its budget authority. Nonetheless, critics still abound and fall into two groups: those that seek to eliminate mining in the U. S.; and those who see the mining industry as a further source of cash to fund various federal programs. Attempts to write a new law to essentially replace the 1872 law have been undertaken in Congress, but cannot garner enough support to move out of committee or to be taken up by both houses of Congress. As I recall, the last major attempt at new bill was in 2009. In any case, as a future professional working in the mining industry, you should have an awareness of the issue. The economic and policy arguments brought forth by the critics boil down to the following four criticisms:

- The law is hopelessly outdated.

- The mining industry is acquiring valuable real estate at prices well below market value.

- Mining claims are often used as a subterfuge to secure land for other purposes.

- The government is giving away valuable minerals for free and simultaneously depleting the supply for future generations.

The first three are unsupported by the facts, which is to say they are fallacious. For your needs in this course, these are refuted as follows:

- Not True. There have been major amendments, in 1920, 1955, 1976, as well as dozens of amendments to tweak the Law and keep it relevant.

- Historically True, Presently False. Land developers, among others, used the Law to obtain patented claims on tracts of common minerals such as stone and gravel; and once they had the patent, or a sufficient number of contiguous patents, they built hotels and other commercial enterprises. The amendment in 1955, i. e. the Multiple Surface Use Mining Act of 1955, curtailed this practice by removing common minerals from the list of locatable minerals in the Law of 1872. This did not completely eliminate the subterfuge, however. Congressional budget action in 1994 was needed to put an end to this abuse.

- False. See #2

- Misleading, and Largely False. The arguments to support and to refute this are very technical. There are solid economic reasons against imposing a royalty structure, although there are small changes that could be made to the financial paradigm that would benefit government without unduly harming the industry. Perhaps the most misleading of the arguments is that the company gets the minerals for free. Strictly speaking, they do get access to the minerals for only a few dollars per claim. However, the mine will generate millions of dollars in tax revenue for the local, state, and federal governments, as well as create jobs and markets for supporting industries. The notion that adequate mineral resources will be unavailable for future generations is a completely unsupported and somewhat absurd assertion given the vastness of mineral resources.

Much has been written on the subject, and on all sides of the subject! I find that an older paper, authored by a well-respected mineral economist from Penn State, provides much-needed clarity on the topic. The paper is available online, and here is the citation:

"Two Cheers for the 1872 Mining Law," Richard Gordon and Peter Van Doren. Cato Institute, Policy Analysis Paper No. 300, April 9, 1998.

There is a clever bit of wordplay in the title of this paper. As many of you know, the expression in English is “Three Cheers for __________” and you fill in the blank for whatever you are toasting or cheering. So, why give only two cheers for the 1872 Law? In the end, the authors conclude that there are a few changes that would improve the Law, and if they can be made, great; but if not, leave the Law alone, because it is not so bad!

This brings us to the end, not only of our examination of the General Mining Law of 1872, but also this Module. We began in Lesson 2.1 with a description of the life cycle of a mine, and this helps us to understand how the pieces fit together. We then described the body of laws that affect mining, with an emphasis on ones that impact the regular activities of engineering professionals working in the industry.

In subsequent modules, we’ll take a closer look at the individual stages of the life cycle, beginning with the Prospecting and Exploration Stages in the next module.