Lesson 6.1 A Framework for Sustainability

Lesson 6.1 A Framework for Sustainability

Sustainability means using resources in a way that meets our current needs without preventing future generations from meeting theirs. It's about finding a balance between what we take from the environment and what we leave behind, ensuring that our actions today don't harm the planet or deplete its resources for tomorrow.

Example from Daily Life:

Consider the simple act of using a reusable water bottle instead of disposable plastic ones. By choosing a reusable bottle, you reduce plastic waste and the demand for new plastic production, which in turn conserves the natural resources and energy needed to produce them. This small change supports environmental sustainability by minimizing pollution and resource depletion.

UN's "Our Common Future":

The United Nations' Brundtland Commission released a report in 1987 titled "Our Common Future," which provided a widely accepted definition of sustainable development: "Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs." This emphasizes the importance of balancing economic growth, social equity, and environmental protection to ensure a sustainable future for all (ref: modified from Wikipedia).

When it comes to using resources, many think of sustainable practices as those that consume resources needed by society, but at a rate no greater than that which will ensure the availability of those resources to futures generations so that they may meet their needs. Usually, it is assumed, if not stated explicitly, that the production of these resources is done without harm to the environment. When I think about mining’s need to be sustainable, I think about an industry whose practices are congruent with society’s values. Let’s try to better understand just what that means to the practicing mining professional.

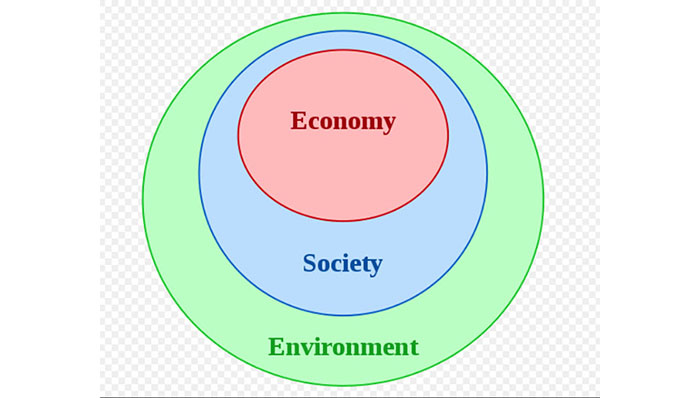

The three dimensions of sustainability are economy, society, and environment; and are represented in Figure 6.1.1, which illustrates that economy and society are constrained by the environment (planet Earth).

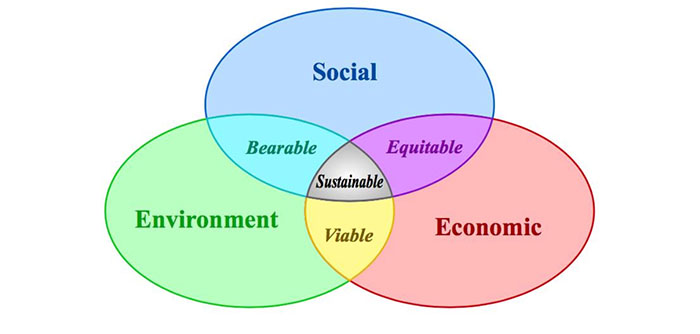

A representation that I like even better is shown in Figure 6.1.2. My preference for this representation lies with the two-way intersections that create the bearable, equitable, and viable regions of the diagram; and then of course, the three-way intersection of these to define the sustainable region of the diagram. The bearable, equitable, and viable regions align well with the sustainability challenges associated with mining and minerals recovery, and we will use this model in our discussion.

For the purposes of this discussion, I’ll use the word project to represent the mining operation. I will generally use both the future and present tenses in this discussion of the regions in the Venn Diagram. IF we are considering a new project, we will most likely be considering future actions, and the future tense is appropriate in such a discussion. Once the project is underway, our actions are occurring in the present, and consequently the present tense is required. Sustainability considerations must guide our present actions on existing projects as well as how we move forward with proposed projects.

I’ll illuminate through examples what we mean by the terms used in the Venn diagram (Figure 6.1.2). Please note that my examples are not exhaustive, but rather are intended to give you a deeper understanding of each term.

6.1.1 Social - Economic

6.1.1 Social - Economic

First, we’ll illuminate through examples what we mean by social and economic, and then we’ll look at the intersection of the two, which forms the equitable region. Similarly, we’ll use examples to illustrate that which many would consider as equitable. Please note that these examples are not exhaustive, but rather are intended to give you a deeper understanding of each term.

The social dimension of sustainability would consider the following questions.

- Will (does) the project improve the infrastructure of the community, e.g. schools, hospitals, water supply, and highways?

- Will (does) the project contribute to the local economy, through tax revenue for example, in addition to creating jobs, and is this contribution in reasonable proportion to the value obtained by the company?

- Will (does) the project provide good-paying jobs within the local community?

- Will (does) the company provide training and education opportunities to improve the skill sets of workers?

- Will it be necessary to displace or move indigenous peoples as a prerequisite to mining activity?

- What will happen to the community or region when the project is completed? Will there be other industries to employ the workers from the former project?

The economic dimension would consider the following question:

- Is (will) the financial performance1 of the project (be) consistent with investor or company expectations?

This single question captures and represents the sum total of everything that affects the cost of bringing a mineral product to market. It also reflects market conditions, i.e. the price at which we can sell our product and the amount of product that we can sell. However, for this discussion, we will neglect market conditions and instead focus on the cost side of the equation. The mining and processing costs will be based on the many factors that we’ve studied in this course, e.g. ore grade, depth of the deposit, geotechnical characteristics of the orebody, the extent to which mechanization and automation can be applied, and so on. Of special interest here are any expenditures that would be made to address the social dimension of sustainability, such as strengthening the community through the improvement of infrastructure.

The intersection between the social and economic dimensions is aptly named equitable. Are the economic benefits that will accrue to society, and in particular the community, in reasonable proportion to the social costs of the project and to the economic benefits that the company will realize from the project? This is a difficult question to answer – how do you calculate this value? While every situation is likely to be somewhat different, there has to be genuine respect for the community and its institutions, as well as a desire by the company to improve the community within the realistic financial constraints of the project.

Unfortunately, it may become even more complicated. Whether or not a solution will be considered equitable can depend on the ethical framework under which the proposed solution is evaluated. Let’s take a non-mining example to illustrate this. Suppose that it is determined that a dam is needed at a certain location on a major river. The dam will provide flood control, sparing towns along the river from the devasting floods that occur every decade or so. The reservoir created by the dam will provide a more stable source of water for communities, and it will create some recreational opportunities as well. In total, thousands of people will benefit if this dam is built. Those are the “positives.” What about the “negatives”? There are a few dozen houses and farms that will become uninhabitable as the water accumulates behind the dam. In some cases, generations of the same families have lived in this area. The entity proposing the dam, which in this case is a government body rather than a private company, will pay the displaced landowners a substantial premium over full market value for their residences. Nonetheless, some landowners do not want to relocate and are opposing the construction of the dam. What to do...

Has an equitable solution been proposed? On the face of it, it would appear so. The landowners who will be displaced will receive sufficient money to relocate and are getting an additional sum of money for their inconvenience. Indeed, this and similar scenarios play out on a regular basis for infrastructure projects, and this is supported by the utilitarian school of ethical behavior. This school is about the greatest good for the greatest number of people. When viewed through the lens of the utilitarian ethic, the proposed project is ethical and this will strengthen the assessment that the action is equitable as well. Many industrial projects, including mineral projects, have long been evaluated under the utilitarian ethic.

In recent years, however, some have been applying another school of ethical thought known as deontology, which is concerned less with what is “good” and more with what is “right.” This is a school of thought concerned with social justice and the idea that basic human rights supersede what is good for society at large. When viewed through this lens, the dam project is unlikely to be deemed equitable, and as a consequence, there are likely to be protests, government appeals, and other actions to derail or delay the project. For mining projects, we have an obligation to address the parameters of the social and economic dimensions to achieve something that will be deemed equitable when viewed through the lens of the utilitarian ethic, and it is in our best interests to try to understand and address concerns when viewed with the deontological ethic. In essence, the evaluation of the utilitarian school is focused on rightness or wrongness of the consequences of actions, whereas the deontological school is focused on the rightness or wrongness of the actions.

1 Financial performance is assessed through metrics such as net present value (NPV) of the project, discounted cash flow internal rate of return (DCFIRR), payback period, and earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA). This will take into account many of the locational, natural and geologic, and socio-political factors discussed in Lesson 4.1.

6.1.2 Social - Environment

6.1.2 Social - Environment

Previously, we looked at a list of questions to help understand the social dimension of sustainability. Now we need to identify relevant questions focused on the environment dimension.

- Will the project adversely affect air or water quality during operations or after the project is completed?

- Will the project create other hazards during operations or after the project is completed?

- Will the project create nuisances, e.g. noxious odors or noise?

- Will the project spoil the landscape, or otherwise reduce the recreational value around the project?

Operating permits, legislation requiring reclamation as well as the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts to protect the air and water quality, guarantee that the environment dimension is well managed... except for the last question in the foregoing list.

The intersection of the social and environment dimensions is identified as bearable. This region represents a solution in which the environmental costs of a project are deemed acceptable when weighed against the social benefits of the project. As with our last discussion of the equitable region, there is no definitive quantification of “bearable,” and as such, it is subject to the interpretation of the parties affected by the project. Consequently, this will likely be interpreted through an ethical lens. The deontological ethic would assert that the environment, including the landscape, its innate beauty, and its enjoyment is a right of everyone; and therefore, regardless of any benefit, no one has the right to impinge on the landscape. Although the surface area of land that is affected by mining is extremely small, it is generally impossible to surface mine without changing the appearance of that parcel of land. It can be reclaimed, and perhaps to even better use than before, but the original appearance is likely to be changed. Indeed, this change in appearance is often an underlying motivator for protests against mining projects.

6.1.3 Environment - Economic

6.1.3 Environment - Economic

We have already identified relevant questions to characterize these two dimensions. A consideration of the intersection, defining the viable region, requires consideration of more specific and technical questions, beyond those already posed. Unlike the considerations of the bearable and equitable regions, the viable region is completely definable by the engineering and science of environmental protection.

We, as engineers, define the engineering steps necessary to protect the environment, in terms of air and water quality, and also in terms of mine closure considerations. Moreover, our reclamation plan can be designed and its costs calculated. Thus, we are able to quantify the costs of protecting the environment. We can even choose to take proactive measures above and beyond those required by any regulations. Of course, that will entail an additional cost, and at some point, the cost of such measures could sink the project. Hence, using the name viable to define the intersection is quite appropriate; and if the cost to protect the environment is too great, the project will no longer be viable.

6.1.4 Sustainable

6.1.4 Sustainable

The intersection of the three regions, bearable, equitable, and viable, defines the sweet spot of sustainability. If you think about it, how could it be anything else? The needs of society for minerals and the needs of the mining company to satisfy the expectations of their shareholders will be balanced against the constraints of the environment and the need to operate in an ethical and socially responsible fashion.

The goal of this discussion has been to equip you with an understanding of the evolving expectations for sustainable development and the ways that society views and evaluates industrial activities such as mining. No doubt you appreciate how difficult it is to establish whether or not something is bearable or equitable, and undoubtedly you can imagine how difficult it could be for a company planning a project over which some are opposed. Despite the uncertainty and fuzzy nature of bearable, equitable, and to a lesser extent viable, there are concrete actions that you can take in the planning and operations stages to facilitate sustainability. We are going to take a look at these in the next Lesson.