Carbon Dioxide Through Time

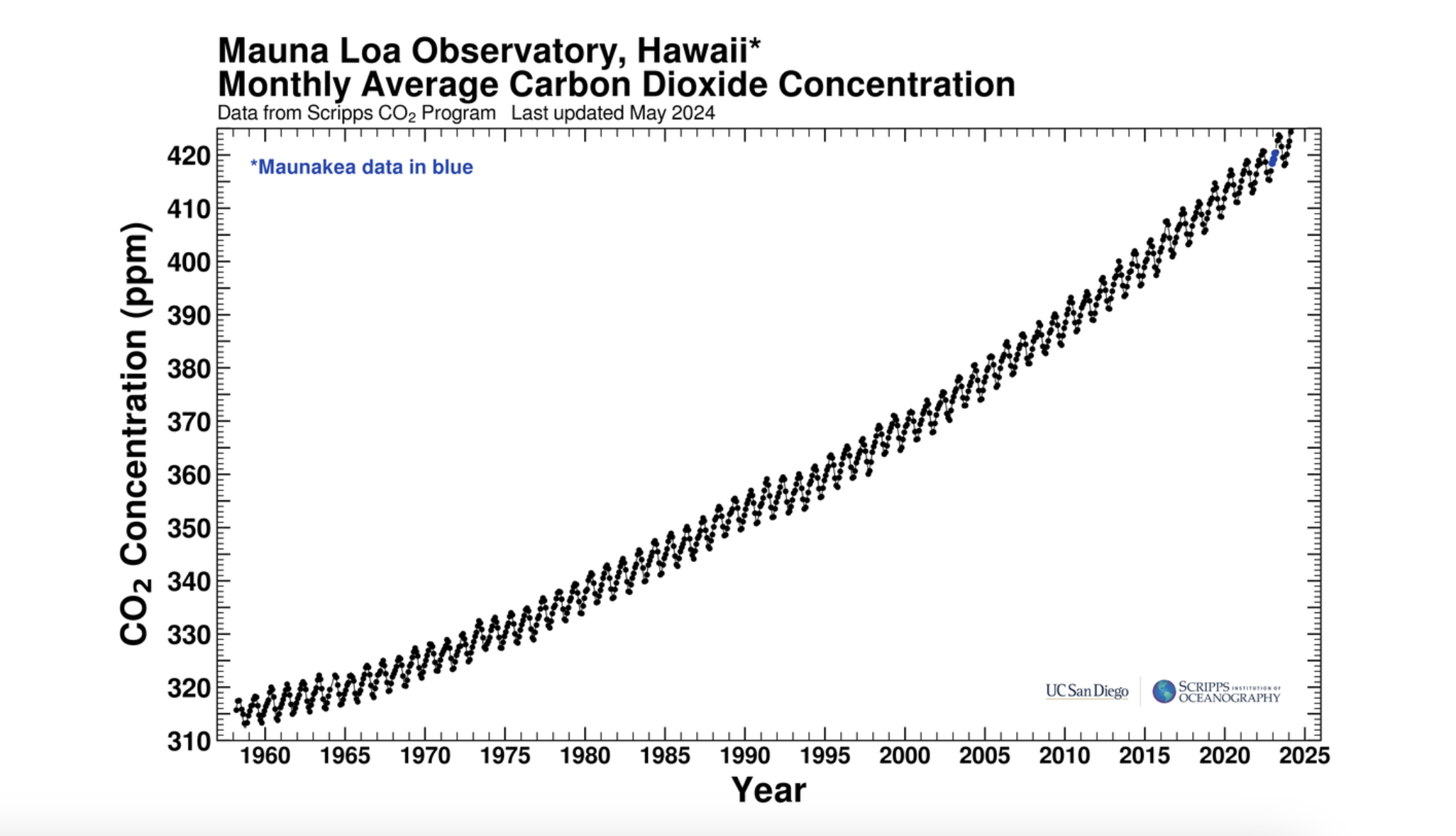

In the late 1950s, Roger Revelle, an American oceanographer based at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California began to ring the alarm bells over the amount of CO2 being emitted into the atmosphere. Revelle was very concerned about the greenhouse effect from this emission and was cautious because the carbon cycle was not then well understood. So, he decided that it would be wise to begin monitoring atmospheric concentrations of CO2. In the late 1950s, Revelle and a colleague, Charles Keeling, began monitoring atmospheric CO2 at an observatory on Mauna Loa, on the big island of Hawaii. Mauna Loa was chosen because its elevation and location away from industrial centers made it as close to a global signal as any other location. The record from Mauna Loa, one of the most classic plots in all of science, shown in the figure below, is a dramatic sign of global change that captured the attention of the whole world because it shows that this "experiment" we are conducting is apparently having a significant effect on the global carbon cycle. The climatological consequences of this change are potentially of great importance to the future of the global population. The CO2 concentration recently crossed the 400 ppm mark for the first time in millions of years! In 2022, the yearly average was 422 ppm (see https://www.co2.earth/daily-co2(link is external) for most up to date estimate).

As the Mauna Loa record and others like it from around the world accumulated, a diverse group of scientists began to appreciate Revelle's concern that we really did not know too much about the global carbon cycle that ultimately regulates how much of our CO2 emissions stay in the atmosphere.

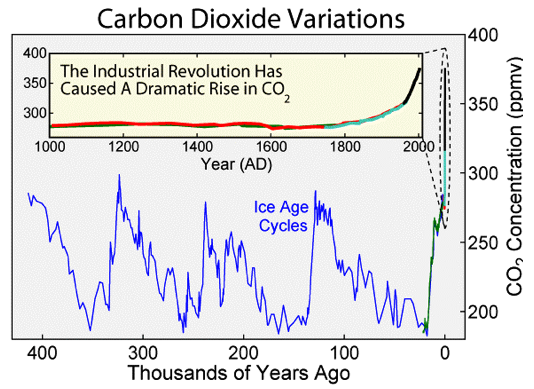

The importance of present-day changes in the carbon cycle, and the potential implications for climate change became much more apparent when scientists began to get results from studies of gas bubbles trapped in glacial ice. As we learned in Module 1, the bubbles are effectively samples of ancient atmospheres, and we can measure the concentration of CO2 and other trace gases like methane in these bubbles, and then by counting the annual layers preserved in glacial ice, we can date these atmospheric samples, providing a record of how CO2 changed over time in the past. The figure below shows the results of some of the ice core studies relevant for the recent past -- back to the year 900 A.D.

The striking feature of these data is that there is an exponential rise in atmospheric CO2 (and methane, another greenhouse gas) that connects with the more recent Mauna Loa record to produce a rather frightening trend. Also shown in the above figure is the record of fossil fuel emissions from around the world, which show a very similar exponential trend. Notice that these two data sets show an exponential rise that seems to begin at about the same time. What does this mean? Does it mean that there is a cause-and-effect relationship between emissions of CO2 and atmospheric CO2 levels? Although we should remember that science cannot prove things to be true beyond all doubt, it is highly likely that there is a cause-and-effect relationship -- it would be an extremely bizarre coincidence if the observed rise in atmospheric CO2 and the emissions of CO2 were unrelated.

How serious is our modification of the natural carbon cycle? Here, we need a slightly longer perspective from which to view our recent changes, so we return to the records from ice cores and look deeper and further back in time than we did in the figure we have been examining.

In addition to providing a record of the past concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere, as we learned in Module 1, the ice cores also give us a temperature record. By studying the ratios of stable isotopes of oxygen that make up the glacial ice, we can estimate the temperature (in the region of the ice) at the time the snow fell (glacial ice is formed by the compression of snow as it gets buried to greater and greater depths). From these data, shown in the figure below, we can see the natural variations in atmospheric CO2 and temperature that have occurred over the past 160,000 years (160 kyr).

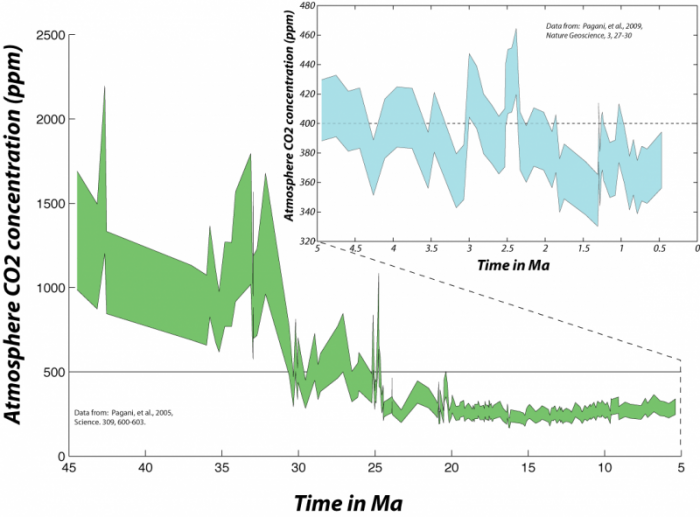

In fact, looking at this much longer span of time enables us to clearly see that the present CO2 concentration of the atmosphere is unprecedented in the last several hundreds of thousands of years. As geoscientists, we are interested in more than just the last few hundred kiloyears, and so we look back into the past using sediment cores retrieved from the deep sea. Geochemists studying these sediments have been able to reconstruct the approximate concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere and the sea surface temperature (SST).

To find atmospheric CO2 levels equivalent to the present, we have to go back 2.5 million years. This means that, to the extent that the state of the carbon cycle is closely linked to the condition of the global climate, we are pushing the system toward a climate that has not occurred any time within the last several million years -- not something to be taken lightly.

The farther back in time we go, the more difficult it is to figure out how CO2 concentrations have changed, but that has not stopped some from attempting:

One thing that is clear is that further back in time, CO2 levels have been much, much higher, and the average global temperatures have also been much higher. Why does the CO2 concentration change so much? This is a big question whose answer involves many factors, but consider two that are relevant to what we'll learn about in this module. Photosynthesis only started in the Silurian (S on the timescale in the figure above), and photosynthesis is a major sink or absorber of atmospheric CO2. Sea level was much higher during the two big peaks in CO2 — this leaves less room for photosynthesis and it also decreases the planet's albedo, making it warmer. A warmer ocean cannot absorb atmospheric CO2 and instead, it releases it to the atmosphere.

In conclusion, from this brief look at the record of fossil fuel emissions and atmospheric CO2 concentrations, it is clear that we have cause for concern about the effects of the global CO2 "experiment". Because of this concern, there is a tremendous effort underway to better understand the global carbon cycle. In the remainder of this module, we will explore the global carbon cycle by first examining the components and processes involved and then by constructing and experimenting with a variety of models. The models will be relevant to the dynamics of the carbon cycle over a period of several hundred years -- these will enable us to explore a variety of questions about how the system will behave in our lifetimes and a bit beyond.