Sidebar: A Brief Chemistry Lesson

Most students reaching the university have taken a chemistry course somewhere along the way, but a few of you haven’t. Here is a BRIEF summary of chemistry, as a refresher for those who have had a chemistry course and as a teaser for those who have not. We do not use a lot of chemistry in this course, but it comes up often enough that you may find a summary to be helpful.

If we pick up anything around us (water, chewing gum, rocks, whatever) and try to divide it into smaller and smaller pieces, we will find that it changes as it is divided. A tree becomes a log as soon as we cut it down. If we dry the log before burning it, we find that it contains lots of water, plus other things that are not water. If we then use fire to break the log into smaller pieces, we find that we can do so, while releasing energy. Using tools and energy levels that are easily available to us, we will find that we can continue dividing something until we get to elements, but that we cannot divide the elements.

The “unit” of an element is called an atom. There are 93 naturally occurring elements, plus others that humans have produced. If we use even higher energies, such as those achieved in nuclear accelerators, we find that we can take atoms apart.

Each atom proves to have a dense nucleus, surrounded by one or more levels where electrons are found. It may prove helpful to think of electrons circling a nucleus the way planets orbit the sun, although this simplified model doesn't capture all the features of an atom.

The nucleus contains smaller particles called protons and neutrons. Protons have a characteristic that we call positive charge, electrons have an equal-but-opposite negative charge, and neutrons are uncharged or neutral. A neutral atom of an element contains some number of protons and the same number of electrons, with their positive and negative charges just balancing each other.

The type of atom, or element, is determined by the number of protons; add one proton to a nitrogen atom, for example, and it becomes an oxygen atom. (Breathing nitrogen without oxygen would cause you to die quickly; they are different!) The positively charged protons packed tightly in a nucleus tend to repel each other, but the neutrons act to stabilize the nucleus. Some elements come in different “flavors,” called isotopes, which have different numbers of neutrons and so different weights. Slight differences in the behavior of isotopes allow us to use them to learn much about certain processes on Earth, as we’ll see later. All atoms of an isotope are identical, and all atoms of an element are nearly identical.

Chemistry includes all of those processes by which plants grow, we grow, wood burns in a fireplace, etc. Chemistry involves changes in how electrons are associated with atoms. An atom may give one or more electrons to another, and then the two will stick together (be bonded) by static electricity, the attraction of the positive charge of the electron-loser for the negative charge of the electron-gainer. An atom that gains or loses one or more electrons is then called an ion. Atoms may also share electrons, forming even stronger bonds and making larger things called molecules.

Most Earth materials are made of arrays of ions, although some are made of arrays of molecules. The ions or molecules usually form regular, repeating patterns. For example, in table salt, a lot of sodium atoms have given one electron each to a lot of chlorine atoms, making sodium and chloride ions. Then these stick together. One finds a line of sodium, chloride, sodium, chloride, sodium, chloride, and so on, and a line next to it of chloride, sodium, chloride, sodium, ..., and above each sodium there is a chloride, and above each chloride a sodium, in a cubic array. A grain of salt from your saltshaker will be a few million sodium and chlorides long, a few million high, and a few million deep.

The properties of the grain of salt—how it tastes, dissolves, breaks, looks, etc.—are determined by the chemicals in it and how they are arranged. We call such an ordered, repeating, “erector-set” construction a mineral. Almost all of the materials in Earth are minerals. Liquid water is not a mineral because the water molecules are free to move relative to each other, but liquid water becomes a mineral when freezing makes ice.

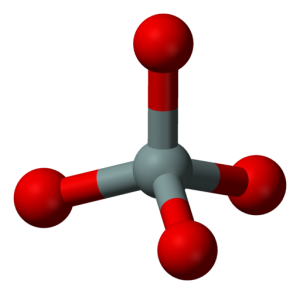

When the Earth formed, we received a few elements in abundance and only traces of the other naturally occurring elements. More than half of the crust and mantle are composed of two elements–oxygen and silicon. Most minerals and rocks thus are based on oxygen and silicon, and we call these rocks silicates. In silicates, the silicon and oxygen stick together electrically, with each little silicon surrounded by four oxygens. Silicon, oxygen, and six others–aluminum, iron, calcium, sodium, potassium, and magnesium–total more than 98% of the crust and mantle. Geology students used to be required to memorize the common elements, and their abundance, in order; for our purposes here, know that only a few are common, and we’ll come back to them later.

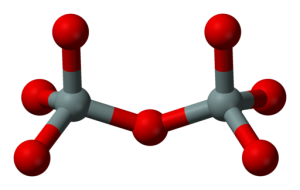

The silicon-oxygen groups form minerals either by sticking to each other by sharing oxygens, or by sticking to iron, magnesium, or other ions. Minerals that contain a lot of iron and magnesium are said to be low in silica, even though they may still contain more silicon and oxygen than iron or magnesium. In general, minerals high in silica are light-colored, low-density, have a low melting point, often contain a little water, and occur mostly in continents; minerals that are lower in silica usually are dark-colored, high-density, melt at high temperatures, and occur on the sea floor or in the mantle more often than in continents. You may hear “basaltic” used for low-silica because basalt is the commonest low-silica rock at the Earth's surface; similarly, “granitic” means high-silica because granite is a common high-silica rock.

Just for Fun—Rockin' Around the Silicates Video (4:24)

We've seen that most of the Earth's crust is made of minerals with silica (silicon and oxygen) in them. Melting these minerals feeds volcanoes, and freezing the melt clogs volcanoes and makes new minerals in new rocks. When we get to the Redwoods and the Badlands in a couple of weeks, you'll see how the weather attacks the new minerals, and you'll meet a few of the minerals being attacked. Here, just for fun, you can see some truly beautiful minerals, and learn a bit about the wonderful ways they are put together—Lego blocks and erector sets have nothing on nature! Meet the main minerals of the crust, in a parody of Bill Haley and the Comets' Rock Around the Clock. This Rock Video has a bit more detail than we'd ever ask in this class, so don't worry about actually learning the difference between nesosilicates and inosilicates unless you're interested.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Dr Richard Alley: (SINGING) Definite chemical composition. Repeating order, each in position controls the growth of the faces crystalline. Minerals, silicates are commonest here. Silicon plus 4 has a friendly face, gets 4 oxygens to share its space. Then little silicon is really hid in a tetrahedral pyramid, SiO4 -4 won't balance out. So put a silicon on the other side, of an O -2 that's nice and wide. Then one extra O electron counts each way, with the O in two tetrahedra to stay, sometimes it pays to share, there is no doubt.

But shared oxygen's not the only way to balance out the charge today. Put a +2 ion in between two oxygens from the pyramid scene. Give iron or magnesium a shout. Share all four oxygens, that's great. You've made a tectosilicate. And half of four with each Si makes SiO2 coming by. That's quartz, but crystals don't work at the bar.

But there's lots of aluminum plus 3 that needs a space where it can be. Take four SiO2 then place one Al in an Si space. K or Na plus balance alkali feldspar. Or kick out Si for two Al that happen by, and balance with Ca +2, Na to Ca solid solution, and then that is plagioclase feldspar.

But if your tetrahedra just won't share, a nesosilicate is there. When each tetrahedron can be found with iron or magnesium all around. SiO4, it's olivine you'll see. Share some oxygens but not each one, so many ways to mineral fun. Share 3 in sheets, the phyllosilicate way, Si2O5s in mica, serpentine, clay, with some other things, gives cleavage that's flaky.

Share one O, tetrahedra form a pair. Si2O7 in the equation somewhere. Sorosilicate, epidote, you know, but we've still a little way to go 'cause some other tetrahedra want to join up, you will see.

Share 2 in a ring, Si6O18, cyclosilicates beryl, and tourmaline. SiO3 sharing two in a line, or Si2O6, that's also fine. Pyroxene, single-chain inosilicate, baby. Join two ions side by side, is it rings or chains? Si8O22 gives you amphibole grains. It's a double-chain inoslicate. Learn the hornblende formula, just can't wait. Half the tetrahedra share 2 Os half share three. Neso, soro, ino, cyclo, phyllo, tecto, silicates-o, tetrahedral Si, and O form the minerals commonest below with Al, Fe, Ca, Na, K, Mg.