6A.3.1 CoreSafety

This discussion and the figures included in Lesson 6A.3.1 are abstracted from National Mining Association materials on CoreSafety and are reproduced here with permission.

Leadership is essential in affecting the behavior of workers. Safety and health performance is directly enabled (or hindered) by the behaviors and decisions of company leaders. Leaders have a responsibility for ensuring safety is integrated into all aspects of the business, holding people accountable for their responsibilities, driving a safe culture, having effective safety systems, and setting a safe example, among many others.

Many organizations that have realized substantial performance improvement have identified leadership development as the catalyst for that change. Leadership development is the process of identifying critical leadership competencies and providing structured development opportunities for leaders to improve those competencies.

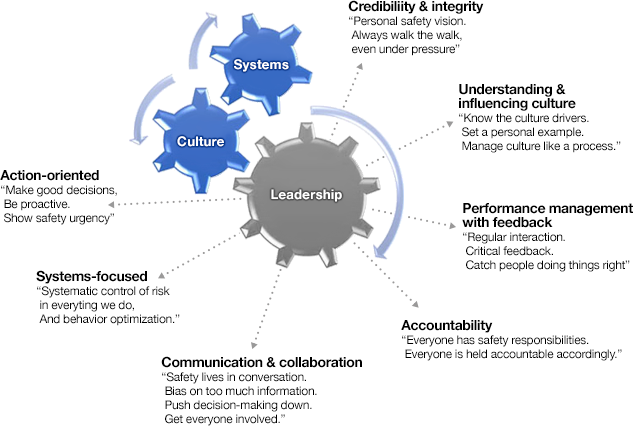

While there are many leadership competencies that are complimentary to safety and health management, NMA has identified eight that are critical in the U.S. mining industry. These competencies include, but are not limited to:

- managing by objective using structured accountability;

- understanding and influencing culture;

- leveraging communication and collaboration;

- having credibility and integrity;

- using performance feedback and management;

- being action-oriented; and

- and understanding management systems and ensuring they work as designed.

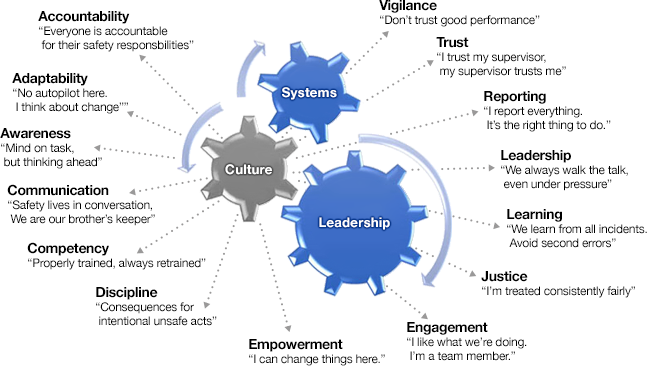

Safety culture can be defined as a pattern of behavior that is encouraged or discouraged by people and by systems over time. This is a very important concept – think about what it means! Do we have a culture that values safety over production? Does the “system” reward us or penalize us if we bring safety concerns to the attention of management? Do we have established committees to look for opportunities to improve safety? We could go on with another fifty questions, but I think you are getting the idea.

Culture determines what we do when no one is watching! This statement makes it clear: if we don’t have a good safety culture, we will be unable to achieve good safety performance. The attributes of a good safety culture are illustrated in Figure 6A.3.3.

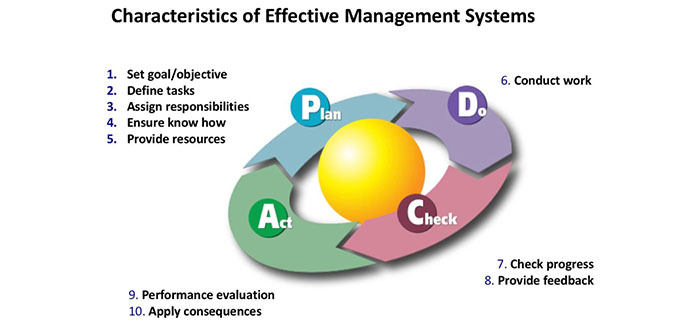

The systems element of the zero-incident framework shown in Figure 6A.3.1 represents those processes and systems used to identify and address hazards. All of these are captured nicely in one overarching system known as the HSMS, i.e. the Health and Safety Management System. Often the order of health and safety is changed, so you are equally likely to see SHMS, i.e. Safety and Health Management System. The content and function of the HSMS is defined by a standard, such as the American ANSI Z10 or the Australian OHSAS 18000. CoreSafety encompasses the best of these standards. An effective HSMS will facilitate an orderly and systematic identification of hazards and the development of solutions to mitigate or eliminate risk associated with these hazards. Further, the system will facilitate the verification that the solution was effective and will incorporate regular audits to ensure that risks are managed. The flow of an effective HSMS system is illustrated in Figure 6A.3.4.

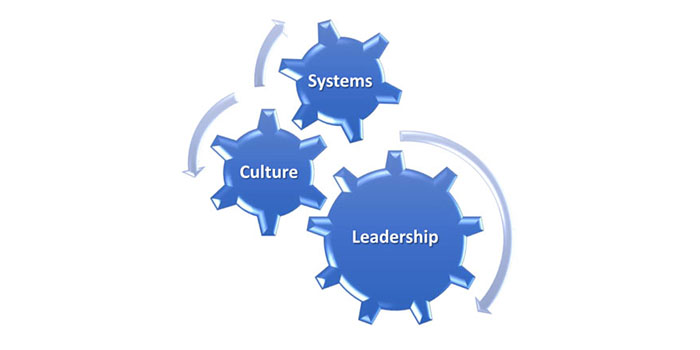

After decades of experience we know that prescriptive regulations are nominally effective, systematic control of risk offers the best opportunity to eliminate fatalities, leadership plays a critical part of improving safety performance, leadership drives culture, and culture affects systems. Figure 6A.3.1 illustrates this relationship. The integration and active management of systems, culture, and leadership can produce world-class performance. Let’s look at each of these elements in a bit more detail.

The circular nature of this diagram draws attention to the need for an ongoing process. Before moving on, a few additional comments are in order.

The Plan phase encompasses five activities:

- Set goals: all risks in all the company’s operations cannot be addressed at once... it is necessary to divide the work into achievable chunks.

- Define tasks: identify the task that will have to be completed. Example tasks could include conducting a site survey, reviewing past accident records, performing engineering calculations, designing risk mitigation measures, purchasing materials or hiring consultants, and installing interventions.

- Assign responsibilities: Clearly identify who is responsible for doing a task AND who will be accountable for the completion of the task. This is one of the points at which the HSMS fails because it wasn’t clear who was doing what, and then things “fall through the cracks.”

- Ensure know how: make sure the people assigned tasks have the knowledge and skills to complete the task. Although this sounds obvious, it is another common failure point within the HSMS.

- Provide resources: It usually requires time and money to implement the actions identified in the Planning Phase. Usually the money is allocated, but often the time is not. Suppose I want to implement a series of tasks for the Bedrock Quarry, and I assign responsibility for conducting the risk assessment to my quarry manager, a task that may take a few weeks to complete. I know that my quarry manager, a Penn State grad, is proficient in conducting risk analyses. Most likely, I have set up a failure at this point! Why? The quarry manager has a full-time job, from 6 in the morning until 6 in the evening, running the quarry. When will she find time to do risk analyses? She won’t. You have to allocate the resource of time if you want to be successful. Maybe we bring in an assistant quarry manager from another operation for a few weeks or find another solution.

Having completed the planning phase, we are ready to spring into action!

The Do Phase is when we conduct the work. This work could include a variety of solutions including developing an offering training, changing certain work practices, installing engineering controls, implementing different operating procedures, and so on.

The Check Phase is too easily forgotten. We identify a problem, craft a solution, and assign people to implement the solution. That’s that! We’re done! Right? Well, not so fast! Things come up, people get distracted by other tasks, and sometimes an unforeseen problem arises, which prevents full implementation of the solution. The bottom line is that someone needs to check to ensure that the solution was implemented and to provide feedback to the people responsible for the planning and doing.

Finally, there is the Act Phase. Based on our planning, doing, and checking, we have the expectation that we’ve successfully eliminated hazards and managed risks. That’s a reasonable belief to have, but it is a belief that needs to be tested. How do we “test” our belief? We assess the effectiveness of the solution. It may be something that we can visually assess through an inspection, or other instances we may be able to look at data to see whether or not a certain category of injury has decreased. Regardless, conducting audits must be a regular occurrence. Although it goes without saying that the findings of the audit must be acted on in a timely fashion, this is another potential failure point. In addition to the performance evaluations that are conducted as part of the Plan-Do-Check-Act process, progressive companies will conduct annual audits of their mines – and here’s the clever part – these audits will be conducted by the manager of a different plant or mine within the company! Nothing like a fresh pair of eyes to spot potential issues.

There is one very important piece to this brief introduction that I want to cover. Think back to the Planning phase. How do we identify risks and prioritize our work for the Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle? That is the missing piece that needs to be covered, and we’ll do that in the next lesson.