Cape Cod National Seashore

Coasts and Cape Cod

Your tour guide, Dr. Alley, is a lucky fellow. Through a fortuitous sequence of events, which involved marrying the right woman who had the right grandfather who was related to some people who have roots in the right place and worked hard to preserve those roots, our family has been able to stay for a week or two during many summers in a wonderfully historic house, built in the 1700s, in Eastham on Cape Cod. The land has been given to the National Park Service as part of the Cape Cod National Seashore. The house has access to the bicycle trail to the Coast Guard Beach, the Salt Pond Visitor Center, and the great Nauset Marsh. Dr. Alley has visited most of the National Parks, but he has spent more time at the Cape Cod National Seashore than any other. A few pictures from his family visits are given in the following slideshow.

Take a Tour of Cape Cod National Seashore

licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0(link is external)

We’ll start here to tell you some background about the Cape in case you want to visit, and to help you understand the geological setting that we will discuss in more detail soon.

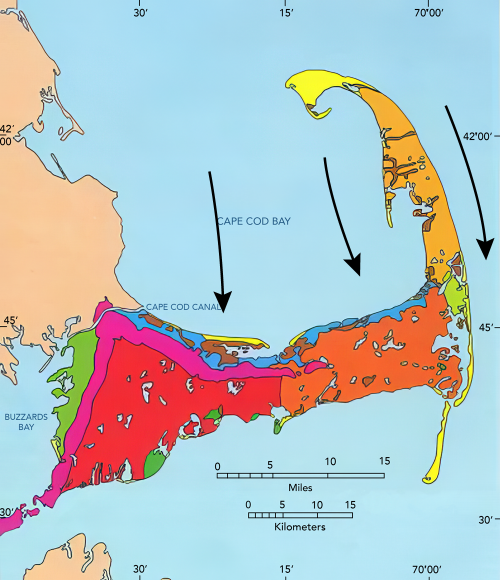

Cape Cod is a glacial moraine, a deposit that outlines the former extent of the ice-age ice sheet that flowed south from Canada. The part of Cape Cod that attaches to the mainland marks the end of a lobe of the Canadian ice sheet. The “forearm” where the Cape points north is an interlobate moraine—while one tongue or lobe of the ice sheet filled Cape Cod Bay between the Cape and Boston, a second lobe lay farther east in what is now the Atlantic Ocean, and built a moraine that is now the fertile fishing grounds of the Grand Banks. (You will see this when you reach the geologic map later in this section.) The northward-pointing “forearm” of the Cape is composed mostly of outwash, the sand and gravel that were transported and deposited by meltwater rivers flowing off these two ice lobes into the narrow space between them. Till, the deposit made from pieces of all different sizes dropped directly from the glacier ice, is found more commonly along the part of the Cape that attaches to the mainland.

The forearm part of the Cape thus is an outwash plain, and most of the numerous freshwater ponds of the Cape began their lives as ice blocks buried in outwash sand and gravel. Melting of the ice later allowed the collapse of the outwash that had been deposited on top of the ice blocks, forming kettle ponds. Soon after it formed, the Cape had more ponds than we see today, but many have been filled with logs, sticks, leaves, peat, and other organic material. The logs and other materials in these former kettle ponds can often be seen eroding out on the bluffs along the Atlantic beach, including along the Coast Guard Beach that is so easily reached from the Salt Pond Visitor Center of the National Seashore. Radiocarbon dates on such deposits, together with other information, show that the ice was retreating from the Cape Cod region roughly 15,000 years ago.

The sandy soils of the Cape, and its numerous kettle ponds, are home to cranberries, blueberries, and wild orchids. Beach plums produce their small but sweet fruit late each summer, and blackberries and dewberries vine across old dunes. Deer and grouse still inhabit the uplands, and turkey are multiplying rapidly as oaks spread across regions that were logged by humans but are being allowed to regrow.

Much of the interest at the Cape focuses on the sea. Nauset Marsh, for example, is a wonderful place to visit for bird-watching, fishing and kayaking in protected waters that are miles long and a good chunk of a mile wide. The protection for the marsh comes from the “outer beach,” a long sand bar between marsh and ocean, which is split by one inlet (or occasionally more inlets, depending on what year you visit) allowing water to flow into and out of the marsh with the tides. Deep channels in the marsh are home to crabs, scallops, starfish and striped bass, often pursued by seals coming in from the open ocean. Between the channels, great flats of marsh grass flood during high tides and dry as the tide falls. Flocks of wading birds and shorebirds, from large herons and egrets to tiny plovers and sandpipers, breed there or stop to feed during their migrations. Osprey survey the marsh from high nests on perches constructed by the Park Service, as well as nests in trees along the shore.

One year, a hurricane had driven unusually warm waters to the Cape, bringing ctenophores from the south. Ctenophores are also called comb jellies, and look something like jellyfish. In the sun these creatures often appear as if they have small rainbows down their sides, because the light is broken on the cilia or hairs that the creatures beat to move themselves around. At night, this particular type (Leidy’s comb jelly) is bioluminescent, glowing with a beautiful blue-green light when the waters around them are disturbed. Imagine, if you can, kayaking into the marsh after dark, with golf-ball-sized “fireflies of the ocean” glowing and swirling with every wave. Another year, tiny phosphorescent plankton (dinoflagellates) were washed into the marsh, lighting up at night with every drip from the kayak paddle and every little fish eating the plankton. Then, fast-moving striped bass slashed through, eating the little fish. (This is a likely reason why the small plankton have evolved to generate phosphorescence, protecting themselves from being eaten by the small fish by notifying the larger, predatory fish.) Indeed, the Cape is a wonderful place.

The Cape is changing rapidly, however. The large Nauset Marsh has been narrowing as the outer beach moves steadily into the marsh. Two of the Cape’s lighthouses were moved during the summer of 1996, barely in time to avoid collapsing over the bluffs into the sea as the bluffs have been eroded away, and the day will come when the light houses must be moved again or else lost.

At the ends of the Cape, to the north and south, new land is being formed, or has formed recently, from the deposition of sand (yellow on the map below). But, more than twice as much land is lost each year as is formed, and the Cape is slowly but surely disappearing. The next ice age might rebuild the Cape, but naturally that ice age is still far in the future, and our global warming is probably already so large and likely to last so long that the ice age will not occur, so the Cape appears destined to become islands and then an undersea bank over the next few thousand years, unless we humans spend a whole lot of money and effort to stabilize it somehow. The long-term retreat rate of the Outer Beach in Eastham has been about 3 feet per year over more than a century, with fluctuations and perhaps with a little recent acceleration.