Rising Sea Level and the Future

Video: Sea Rise (2:26 minutes)

Coasts change for many different reasons, and in many different ways. But, recently, most of the U.S. (and world) coasts have been retreating because sea level is rising, and that rise is accelerating. The total size of the ocean is increasing, as water that had been stored on land in glaciers and ice sheets and in the ground is transferred to the ocean, and as warming of the ocean causes the water already there to expand and take up more space.

The rate of rise is now more than 3 mm/year (a bit over an inch per decade), and has been accelerating. That isn’t much if you’re at the top of a cliff in Acadia, but if you are on a sandy beach that slopes very gradually, the inch of sea-level rise may cause the coast to retreat by many feet or even a few tens of feet. That in turn means that a whole lot of houses and property can be lost in a single human lifetime.

This ongoing sea-level rise is being caused primarily by the rising temperature of the Earth’s climate (“global warming”), which is being driven primarily by human activities. (We’ll return to this later in the course, but we have very high scientific confidence that it is correct.) Most of the world’s small glaciers have been melting, Greenland’s ice sheet has been melting and flowing faster into the ocean, and Antarctica’s ice sheet has been flowing faster into the ocean, adding water to the oceans. Also, as the ocean itself warms, the water expands and takes up more room.

We also build dams on rivers, and the water that fills the reservoirs is taken out of the ocean and stored on land, causing sea-level fall. But, we “mine” groundwater by pumping it out of the ground faster than nature puts it back, and that water eventually reaches the ocean to raise sea level. Today, groundwater pumping is probably more important than dam building, contributing a little to sea-level rise.

The polar ice sheets contain a huge amount of water—if they melted, they would raise sea level nearly 250 feet (roughly 70-80 m). Philadelphia and the other great port cities of the world would become undersea hazards to shipping but really great places for fish to hide out, and the southern coast of Florida would be somewhere up in Georgia. We do not expect such a fate, but we cannot rule out the possibility that a dynamic collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet could raise sea level more than 10 feet (3 m) in a human lifetime or two. If we don’t change our behavior, Greenland and its 24 feet of sea level is also looking shaky, although it would take centries or longer to melt completely. (Melting all of the remaining mountain glaciers would raise sea level only 1 foot or so, less than 0.5 m.) Drs. Anandakrishnan and Alley spend a lot of their research trying to reduce our uncertainty about the future of the great ice sheets, a fascinating and important topic.

Policy Implications of Sea-level Rise

Even if we humans stopped warming the climate, sea level will rise at least somewhat more, because much of the ocean has not yet fully warmed from the atmospheric warming we have already caused but will continue warming to “catch up” with the warmer air, and more ice will melt before reaching equilibrium with the warming of the air we have already caused. (If you come into a cold house in the winter and turn up the heat, it will take a while until everything feels warm; we have turned up the heat in the air, and it will take centuries for the ocean and the glaciers to fully catch up.) The near-certainty of continuing sea-level rise has some policy implications. For example, disaster aid following hurricanes that allows people to rebuild in vulnerable places will simply create the need for more disaster aid in the future. Many people believe that those who wish to build on the coasts should be required to carry insurance or to otherwise demonstrate that they have sufficient resources to cover their coming losses. Similar arguments apply to those who wish to build on earthquake faults, landslide deposits, and floodplains. Many people living in relatively safe but less-scenic places object to paying for others to live in dangerous but beautiful places.

Engineering Solutions

Because people love the coasts so much, and wish to live near them, all sorts of engineering solutions have been tried. These have had some success, but many failures, and they often lead to legal and political difficulties.

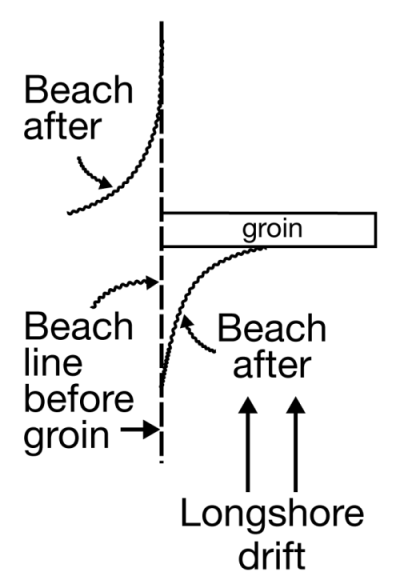

One approach is to build “dams” that stick out into the water and block the longshore transport of sand. These dams are usually called “groins” if they are small, and “jetties” if they are larger. (See the figure above). By making the coast rougher, and slowing waves, the plan is to trap sediment along the coast in much the same way that a dam traps sediment along a river. This plan sometimes works. However, recall that when a dam is built on a sand-bedded river, sediment is trapped upstream of the dam but eroded downstream. The same often happens along a coast; sediment is trapped “upstream” of the groin (on the side from which the longshore drift comes), but sediment is eroded on the “downstream” side (the side to which the longshore drift goes), where the sand-free waves attack the beach to pick up more sand. Saving someone’s beach while destroying the beach of a neighbor is a good way to generate lawsuits.

Video: Groins (3:14 minutes)

People also spend millions of dollars to go out to sea, find sand that has fallen off into deep water, and bring the sand back to the beach. This sand usually lasts a single year or a very few years before being washed back to deep water, and in one recent case was mostly washed away in less than a week, but in some especially popular tourist destinations the investment may pay off.

We saw earlier that people do other things, such as building giant walls to keep the sea out. In the case of New Orleans, huge amounts of money were spent building a levee system, and then people built their houses and businesses in the supposed safety behind the levees. When hurricane Katrina broke the walls, the losses included the cost of building the levee system, the valuable things that the levees were built to protect, and the new valuable things that people built after the levees were erected, as well as the lives of so many people.

Geologists often look at such past events and then take a “natural” view of the coasts—we should figure out where the coast wants to go and build there rather than trying to stop the coast. But many people just don’t like that, and a lot of construction is likely to occur—and be destroyed—over the coming years, especially if we drive more warming.