Arches National Park

Arches National Park is just outside of Moab, Utah, almost within shouting distance of Canyonlands. Arches National Park has the largest concentration of natural stone arches in the world, with dozens of major arches, numerous other holes, and many more interesting rock features. The longest natural arch in the USAis there, Landscape Arch, spanning about 300 feet (almost 100 meters). Several rockfalls have occurred from Landscape Arch since European settlers arrived, reducing the arch to a thickness of only 11 feet (3 m) in its thinnest part. The trail under the arch has been closed; the Park Service knows that eventually more rocks, and the whole arch, will fall, and the rangers do not wish to be involved in extracting compacted humans from beneath the remnants of what used to be the USA’s longest arch.

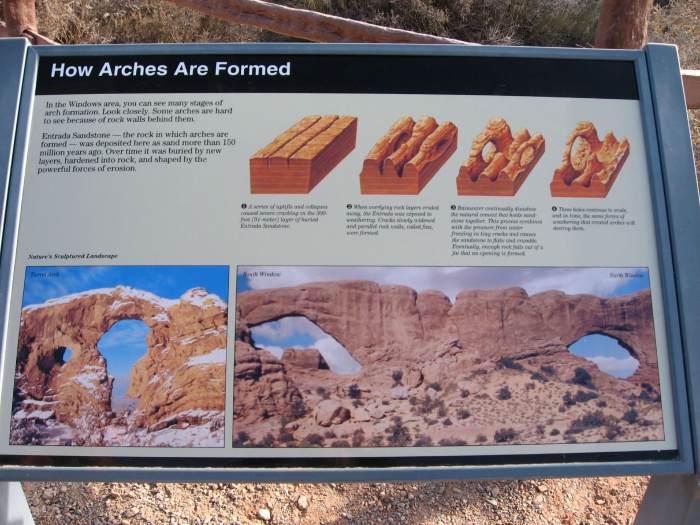

The arches are all eroded in sandstone, especially the mid-Mesozoic (deposited during the time of dinosaurs) Entrada Sandstone, which includes both marine and wind-blown sands. Arch formation started with the deposition of thick beds of salt in the Arches area. Sediments including the Entrada sands were deposited on top of the salt, and cemented by hard-water deposits to make sandstone. When the weight of those sediments became large enough, the salt began to flow, squeezed from places where thicker sediments caused higher pressure on the salt, to places where thinner sediments gave lower pressure, like ketchup in a fast-food packet squeezed from one place to another. However, the foil wrapping of a fast-food packet is fairly flexible, but the Entrada sandstone was not, so as the salt moved, the tough sandstone broke, forming cracks called joints. The most common joints formed by this motion are parallel, nearly vertically oriented, and a few yards (or meters) apart. Weathering processes attacked the rocks along these joints, which were slowly widened to leave vertical slabs of rock called fins.

Some weathering and erosion processes are more effective near the ground than high up. For example, you will see huge steel bolts sunk into the rock of some road cuts just above the highway to keep the weight of the rock above from popping slabs of rock loose that might blast into the road and kill people; such rock-bursts also occur in quarries if actions are not taken to avoid them. When such slabs of rock break from a cliff or fin or fall, they often leave a curved or arch-like top, because it is easier to break off a curve than a square-cornered piece. This process is among those that contribute to the arch formation, breaking through the fins to make beautiful stone arches.