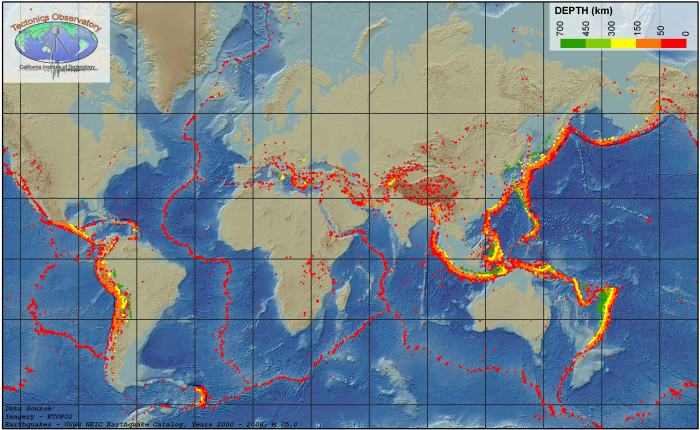

Where Quakes Occur

Earthquakes, as noted above, occur where rocks are moving past other rocks. We have seen that this happens where rocks are being pulled apart, as in Death Valley, because the breaks often are angled rather than vertical, and the upper side slides down over the lower. We will see that there are other situations in which rocks are being pushed together, or that rocks are sliding past each other as at the San Andreas Fault, and these also can make quakes. This mostly occurs near plate boundaries. Volcanoes can cause small to medium-sized quakes as well when moving melt pushes rocks aside or leaves spaces into which rocks fall.

Quakes also occur at weak spots in continents. Often, when a continent is splitting open at a spreading ridge, the tear assumes a 3-armed form, something like many large wind turbines. (Poke your finger through a piece of paper and you’ll often get the same thing.) Two arms then grow into a spreading ridge that forms an ocean, and the third arm fails. Major rivers often form in such failed rifts. When the Americas split from Africa and Europe as the Atlantic Ocean grew, failed rifts became the river beds of the Amazon, the Niger, and the Mississippi. You open a fast-food ketchup packet by tearing at a little notch cut in the foil because the notch weakens the foil. If the notch isn’t there, you may have to poke a fork through or end up saying bad words, because the packet is much harder to tear without the pre-existing notch. In the same way, earthquakes can occur at the tips of failed rifts, which are the “notches” in the “foil” that is the lithosphere of the Earth. Some of the largest quakes known to have occurred in the U.S. were located at the northern tip of the rift along which the Mississippi flows, near New Madrid, Missouri. (Scientists are fairly confident that more large quakes won’t occur there soon, although there is still some slight chance.) Quakes also are known from an old weakness near Charleston, South Carolina.