Predicting Earthquakes

A tremendous amount of effort has gone into trying to predict earthquakes. This is because they are so destructive of life and property. Seventeen quakes are estimated to have killed more than 50,000 people each, and the worst, in Shaanxi, China in 1556, is estimated to have killed over 800,000. (In the U.S.A., the worst death toll was 503 in the San Francisco quake of 1906.) The magnitude 9.0 Tohoku earthquake in Japan in 2011 killed over 15,000 people, although the toll would have been far, far worse if the Japanese had not put so much effort into making strong buildings and otherwise planned to reduce the damages. Earthquakes usually kill by dropping pieces of broken buildings on people, but also by triggering tsunamis (big waves) or landslides, and by breaking gas lines or other things that cause fires.

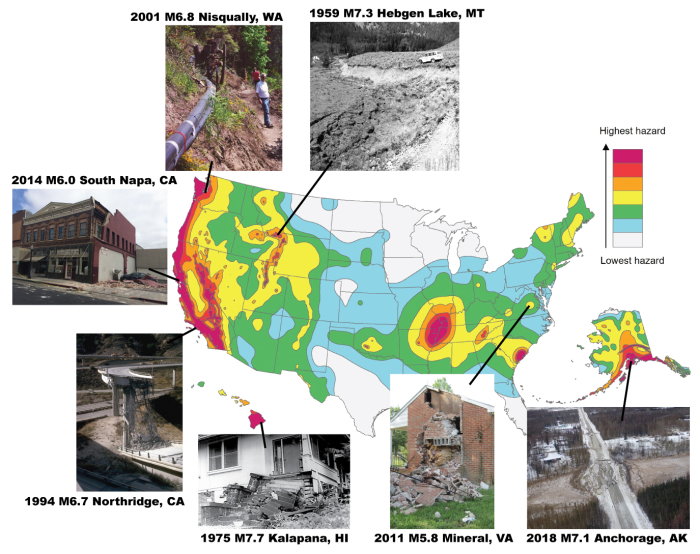

The easiest way to “predict” quakes is to identify those places where quakes are likely to occur. This can be done from historical records, patterns of large, slow ground motions measured by GPS, and prehistoric geologic evidence. A lot of landslides of a single age in a region, or drowned forests related to land subsidence into the sea or large lakes, may indicate the effects of an earthquake. Once people know where quakes are likely, appropriate zoning codes for buildings can be enacted. Spending a million dollars on special engineering for a building to survive quakes is wise indeed near the San Andreas Fault, and helped Japan, but may not be necessary for central Pennsylvania, where big quakes are considered to be highly unlikely.

Other ideas have been advanced for predicting quakes. One is to use patterns of seismicity. If one section of a fault has had a quake every 20 years for the last century, you might expect another quake 20 years after the most recent one. Also, a fault that is slipping and moving may have lots of little quakes, whereas a locked fault that is building to a big quake may have no little quakes. So, you could use such a no-quake “seismic gap” in predictions. Such a pattern—historical repeats and a seismic gap—was used in the year 1984 to predict a quake in approximately 1993 near Parkfield, CA on the San Andreas Fault. The quake occurred in 2004. A possible explanation for the delay is that there are many faults in that part of California, and several big quakes occurred on faults near the San Andreas shortly before the expected quake. These certainly perturbed the state of stress at Parkfield, at least delaying its quake. (The other quakes allowed rocks to move, and even caused some faults to run backward compared to their normal behavior for a while, taking the load off and delaying the next quakes.) This illustrates the difficulty of predicting quakes. Perhaps, if the motions of all of the important blocks were monitored, one could model the whole system and do a better job of predicting where stresses are accumulating. Such work is ongoing, including important work by Penn State scientists, but reliable predictions are not yet available and may never be.

Even if pattern predictions of earthquakes can be made to work, the predictions are unlikely to be precise enough to tell us what we want. Knowing that a quake will occur sometime in the next few years, or even the next few days, does not allow us to get people out of old buildings, off bridges, etc., during the quake. The best hope for predictions within hours or minutes is to find premonitory events. As the stresses build toward failure, rocks may begin to crackle, groundwater may move around in the cracks so that water rises in some wells and falls in others, electric signals may be given off by the cracking rocks, and animals may act strangely. The difficulty is that groundwater rises and falls in wells for many reasons, strange actions in an animal may indicate bad feed, mating season, or any number of other causes, and other premonitory events of earthquakes also have non-earthquake causes. The subtle clues to an earthquake may be recognized using 20/20 hindsight, but no one has figured out how to read them in advance. The possibility is there, though, waiting for brilliant insights and hard work by some interested researchers. (After a big quake, lots of people typically show up claiming that they predicted it, but none of these “predictions” has ever been verified. And, many people, including some scientists, have made predictions of particular earthquakes to come, but again, these predictions have not proved to be useful.)

Take a Tour of Alaska and San Francisco

Visit Alaska and San Francisco to get a glimpse into the effects of major earthquakes.